What the Internet Was Like in 2007

The iPhone and Android both launched in 2007. But it was still a desktop web, with social networking sites like Facebook, Twitter and Tumblr keeping people glued to their computer screens.

2007 is often thought of as the year of the smartphone, with both the iPhone and Android launching that year. But for much of the year it was still a desktop-driven web, with emerging social media sites like Facebook, Twitter and Tumblr typically read and updated on a computer screen. Meanwhile, online advertising boomed in 2007—including via two big acquisitions by Google and Microsoft—and Netflix began branching out into video streaming.

Smartphones Arrive

There had been rumors of a combined phone and iPod device coming from Apple, but what Steve Jobs announced at Macworld on January 9, 2007, blasted away all expectations. Using his trademark showmanship, Jobs calmly announced that Apple was “introducing three revolutionary products,” which he described as an iPod, a mobile phone, and an internet communicator. He repeated these three ingredients several times, slowly building the anticipation and eliciting whoops and anxious laughter from the audience. Then he delivered the punchline: “These are not three separate devices; this is one device—and we are calling it iPhone.”

The biggest difference from existing mobile devices—like the Motorola Q, Nokia E62, Palm Treo, and the BlackBerry—was that the iPhone didn’t have a QWERTY keyboard. Instead, Apple was introducing a patented touchscreen. This would change everything in mobile computing.

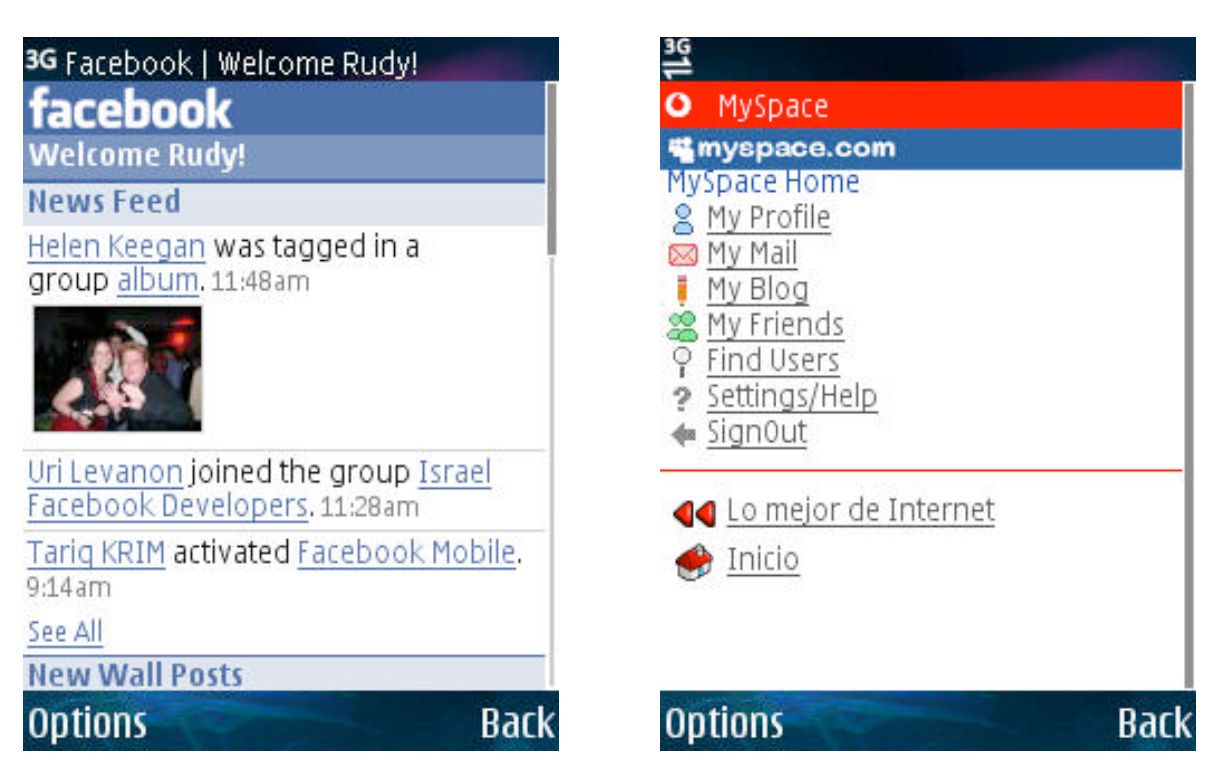

However, notably absent from the first iPhone—released in the US in June—was an App Store. For the rest of 2007, browsing on the iPhone would be done on Apple's Safari browser. For this reason, and also because the iPhone wasn’t widely available outside the States for another year, 2007 was a transition year for the smartphone revolution. Apple had opened the door to a mobile future with the first iPhone and iOS operating system, but Web 2.0 remained focused on desktop computer users for now.

Two other notable mobile computing products were announced in 2007. In November, Google announced its iOS competitor: an open-source mobile operating system called Android (but the first phone running Android would take almost another year to arrive). Also, Amazon announced its eReader product, Kindle.

The Birth of Streaming

Just a week after the iPhone announcement, a DVD rental service called Netflix launched a limited streaming service. One thousand movies and TV series were made available to download on the internet over the next six months (it had seventy thousand titles on DVD). Up till this point, Netflix had helped popularize Web 2.0 via its website, which featured a slick user interface, algorithmic movie recommendations, ratings, and a “friends list” for sharing movie trivia. But now it was inching into the next era of Web 2.0, what we’d soon come to know as streaming and apps (although the word streaming wasn’t yet being used—Netflix called it “electronic delivery”).

Hulu, a joint streaming venture between News Corporation and NBC Universal, launched on October 29, 2007 as a private beta. But, similar to the smartphone market, it wasn't until the following year that major traction happened for streaming companies like Hulu and Netflix.

Social Web Ramps Up

A lot was happening in social media over 2007. In February, Tumblr launched—it was a way to create tumblelogs, which it said were “blogs with less fuss and more stuff.” In October, a startup called FriendFeed launched and quickly gained a cult following among geeks—it was basically an aggregator of RSS and social media feeds. The same month, Google launched OpenSocial, a set of APIs that allowed developers to build an application once and install it across a variety of social networks.

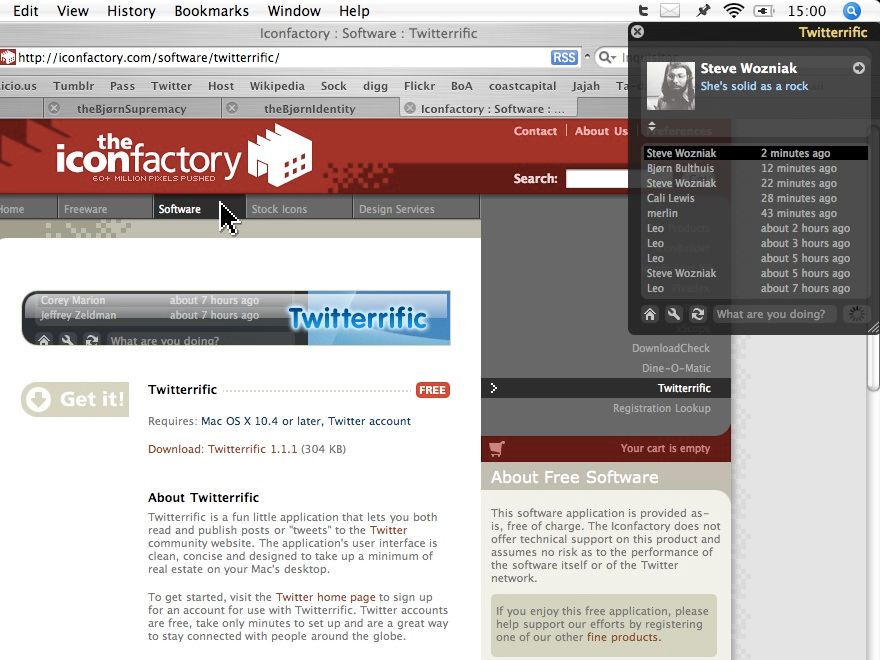

But the most notable new social media product of 2007 was undoubtedly Twitter. The first wave of people to join Twitter was in March 2007, when it became the trendy app at the annual SXSW conference in Austin, Texas (I myself signed up the following month).

More than any other internet product before or since, with the possible exception of TikTok about a decade later, Twitter was massively genre-busting. In a post about a month and a half after I joined, I described it as an “IM/blogging hybrid.” A colleague of mine called it “a new form of communication that is both a natural step from blogging and a weird experiment normally found in neuroscience labs.”

The most interesting thing about Twitter back in 2007 was that developers were building third-party tools for the product, which Twitter co-founder Biz Stone said drove ten times more traffic than the official website.

No doubt spurred on by Twitter's API activity, in May 2007 Facebook announced a developer platform that enabled third-party companies to integrate their services inside the fast-growing social network. It’s strange to think now, but at the time Facebook was not the most popular social network on the internet—particularly outside of the United States. Facebook had twenty-four million global users at its platform launch, but it was far behind MySpace at sixty-seven million. Indeed, in some countries, Facebook was the third biggest social network (in the UK, Bebo was more popular than MySpace).

But part of the new appeal of Facebook was that third-party developers could potentially make money from their apps, thanks to the developer platform. “You can build a real advertising business on Facebook,” Mark Zuckerberg told developers and journalists.

Online Advertising Boom

Zuckerberg was onto something, because by 2007 the Web 2.0 industry was big business. This was confirmed by the sale of two large advertising networks to tech companies in the first half of the year. First, in April, Google acquired the online advertising platform DoubleClick for $3.1 billion. Microsoft quickly countered the following month by buying a digital marketing company called aQuantive for $6 billion. While my blog ReadWriteWeb didn’t use those platforms, it was among the beneficiaries of record internet ad spending that year.

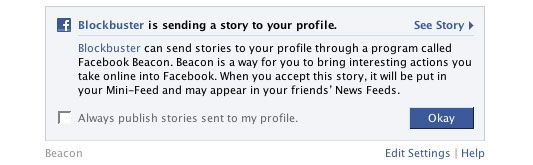

However, the dangers of online advertising to end users became apparent in November, when Facebook waded into a privacy controversy. It launched a new advertising system called Beacon that allowed its users to share things they do across the web to their Facebook news feeds—for example sharing an eBay listing with their friends. RWW described Beacon as “an attempt at conversational marketing, where users become product promoters.” The problem was, the system also allowed Facebook’s advertising partners to gather user data—sometimes without a user’s knowledge—for targeted advertising.

Beacon wouldn’t be the first time Facebook tested the boundaries of user privacy, but somehow the company still managed to fend off its competition and continue growing. And with smartphones poised to make inroads in 2008, Facebook—and the rest of the tech industry—were fully expecting the internet good times to continue.

Read next:

- What the Internet Was Like in 2004

- What the Internet Was Like in 2005

- What the Internet Was Like in 2006

- What the Internet Was Like in 2008

- What the Internet Was Like in 2009

- What the Internet Was Like in 2010

You're reading Cybercultural, an internet history website. Subscribe for free, or purchase a premium subscription. Your support for this indie publication would be greatly appreciated.