Read/WriteWeb Makes Key Hire & I Meet Hustle Culture

Marshall Kirkpatrick joins Read/WriteWeb in September 2007. The following month, I attend the Web 2.0 Summit and experience the start of hustle culture.

In August 2007, I began discussions with Marshall Kirkpatrick, a former TechCrunch lead blogger who was now working for a marketing company. Marshall was from Portland and working for a local company called SplashCast when I reached out to him by email. I asked if he knew of any freelance bloggers who might like to work for Read/WriteWeb for around twenty hours per week. He emailed back, suggesting himself. It turned out he was thinking of leaving SplashCast to do consulting work, so he was open to another blogging gig. “If it’s not me in particular that you’re looking for, I’ve got a list of more than 30 bloggers now looking for blogging gigs, some of them very accomplished,” he added.

Of course, I was looking for someone exactly like Marshall—he’d started out his tech blogging career in October 2005 working for AOL’s social software blog (under Jason Calacanis) and then went to TechCrunch for a six-month stint in mid-2006. Other than myself and other pioneering tech bloggers like Mike Arrington and Om Malik, no other freelance blogger had more experience in our fledgling industry.

Marshall (on the right) at SXSW 2007; photo by Scott Beale / Laughing Squid

I asked for the going rate for bloggers and for what he himself was looking for. He said that a half-time blogger would normally be in the price range of $2,000 to $4,000 per month, “depending on how much competition there is for the writer.” He offered his part-time services for a monthly rate of $5,000, a 25 percent premium on the top rate he’d just quoted. Marshall was still in his twenties at this point, so I had to admire his self-confidence. I’d consistently undersold myself in the job market prior to starting RWW, and it had always bugged me (once I was old enough to realize that I’d been duped). So I wondered if this was a cultural difference—did Americans just naturally value themselves higher than average?

I counteroffered with $4,000 per month. Even that was more than I was paying Josh Catone for thirty hours per week, but I was confident Marshall would make an immediate impact on RWW. At TechCrunch he’d been known for his breaking news coverage. Josh was more of a feature and profile writer, and I wasn’t a natural newshound, so I realized that Marshall could be transformational for RWW. At the very least, it would make the site more competitive with the likes of TechCrunch and Mashable—both of which were covering the daily tech-news cycle.

I was impressed by Marshall’s high rating of his own ability, but of course I didn’t know him very well at this point. I needed to see if he’d live up to his own hype, so I suggested we do a trial run of three to four months, “to see if we work well together and we’re both happy, etc.” I also hinted that I’d consider offering him a small stake in RWW at the end of the trial period if he joined us full-time.

He agreed. “I’m an ambitious guy and am really excited to be a part of the RWW team—I’m damn proud, in fact,” he said. “I think we’ll work great together.”

I didn’t yet have a legal template to use for a freelance contributor—another thing I needed to sort out from a business perspective. Luckily, Alex Iskold gave me a consulting agreement template that he used for his company, so I filled in Marshall’s details and sent that off. In mid-September I announced on the site that Marshall was joining RWW.

The site’s focus would still be analysis of Web 2.0, but once Marshall joined, the amount of news and reviews on RWW naturally increased. My plan was for Marshall and Josh to provide all the news, while Alex, Emre, and some other regular contributors joined me in doing weekly analysis posts. All up, we were aiming for about seven posts per day—five news and reviews, the rest longer analysis posts. This was still a lower volume of daily posts than TechCrunch and Mashable, but I didn’t want to go all-in on news like those sites. I was always aware that people came to RWW for explanation and analysis, so that had to be balanced with the need to cover the news cycle. We weren’t as broad as our competitors in what we covered, but we went deeper.

One thing I hadn’t considered when bringing Marshall on was the impact it might have on Josh. Marshall was several years older than Josh, plus he’d had prior experience as the lead blogger at the biggest tech blog. Many months later, Josh told me that he felt like a “second fiddle” once Marshall joined and that his work had, at times, become marginalized. I was largely unaware of this issue at the time, but it would be my first taste of the challenges of people management. Bloggers, I soon discovered, had egos—and it would take some deft leadership skills to keep a team of them in check. Marshall’s blogger ego was particularly buoyant, but he also walked the talk. We had an immediate uptick in web traffic once he joined.

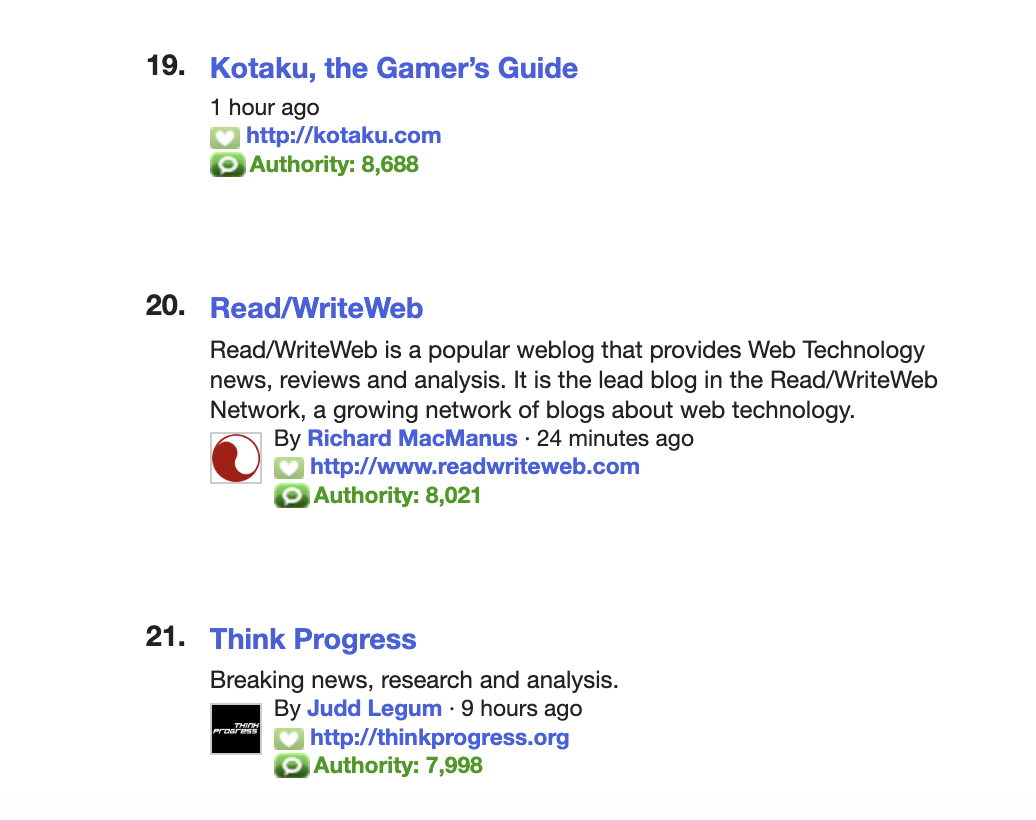

By the first week of October 2007, RWW had cracked the top 20 of Technorati’s list of the world’s most popular blogs. Of our direct competitors, only Mashable (8) and TechCrunch (4) were ahead of us. It was a milestone for our small but growing team.

Cracking the top 20 of the world’s most popular blogs.

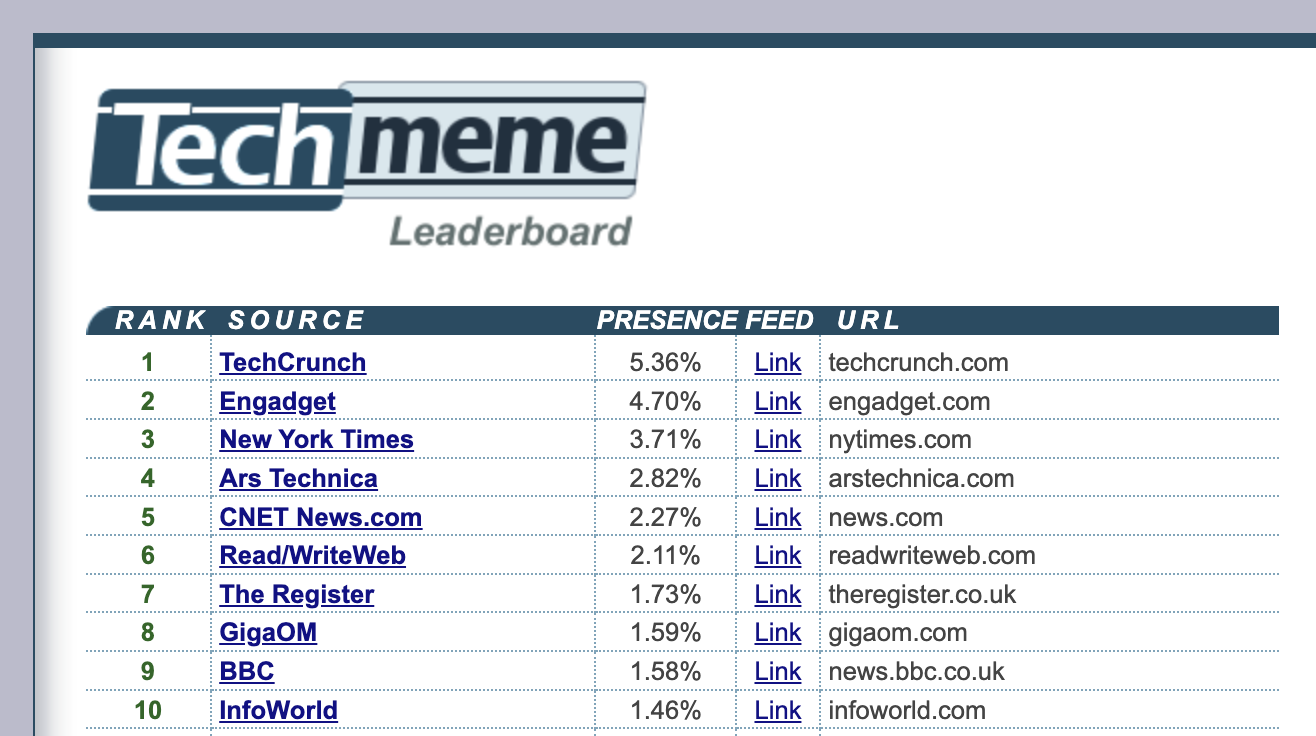

We’d also been ranked number 6 on a new “leaderboard” feature at Gabe Rivera’s Techmeme site, the industry’s leading aggregator of tech news. Unsurprisingly, TechCrunch was the top-ranked site. The New York Times and CNET were also among the top five, but RWW had been ranked ahead of many other mainstream media websites, including the BBC, InfoWorld, and Wall Street Journal.

RWW was among the 10 most important sources for Techmeme by October 2007.

This prompted a discussion on the blogosphere about “new media” versus traditional media. My take was that the top blogs on Techmeme’s list had “evolved into media companies.” I claimed, somewhat tongue in cheek, that RWW “isn’t a blog and hasn’t been for some time—at least in the classic definition of a blog as a personal journal.” I added, however, that I was still a blogger.

We’d shortly experience one of the downsides of increasing popularity—web server strain and other technical issues associated with scaling—but for now I was busy preparing for another US trip. The Web 2.0 Summit was happening again in mid-October, and I was excited to attend for the third straight year.

I touched down at SFO on Sunday, October 14, and took a taxi to the Adante Hotel on Geary Street. It was a run-down establishment, but it was inexpensive and a nice ten-minute stroll to the Web 2.0 Summit venue—the much plusher Palace Hotel.

The summit would start on Wednesday, but I had a busy schedule at the start of the week. On Monday I attended a small event at the Grand Hyatt called Mobile 2.0, which an occasional RWW guest blogger named Rudy de Waele had helped organize. Much of the talk at the event was about mobile apps in Japan and South Korea, two countries that were years ahead of the Western world on mobile web technologies—although still prehistoric compared to what the iPhone App Store would soon unlock.

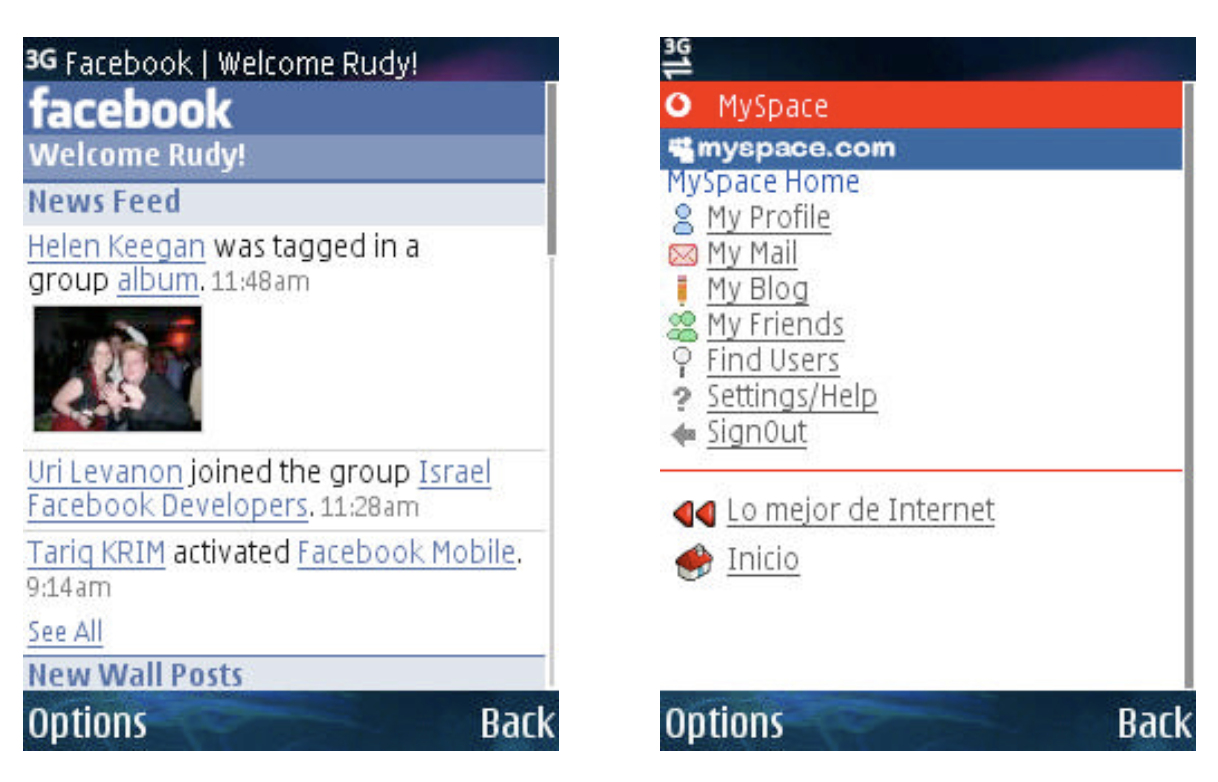

Rudy’s presentation posed a question: “Is Web 2.0 going mobile?” To answer that, he showed a screenshot of the Facebook mobile web page on a 3G phone: an anemic-looking site with pitifully small photos and an awkward menu. So no, Web 2.0 hadn’t yet gone mobile. Come back next year.

In October 2007, the mobile web was still browser-based (or WAP-based!). Screenshot via Rudy de Waele.

Later that day I met up with GigaOm’s founder, Om Malik. I walked down to one of his local Starbucks, in the Embarcadero neighborhood on the eastern waterfront. It was the first time I’d sat down with him for a chat, but he greeted me like an old friend. Then in his early forties, Om had flecks of silver in his hair and cut a dapper figure in his button-down blue-checked shirt and tan slacks.

Om was a well-connected tech journalist and much liked in the tech industry by both entrepreneurs and other bloggers. Like Mike Arrington, Om was an insider in Silicon Valley—although he was much more relaxed and comfortable with this status than Mike ever was. At the time we met, RWW had only recently taken over from GigaOm as the third-most-popular tech blog covering Web 2.0, according to Technorati. Om showed no signs of this bothering him, even though his blog was the closest to mine in terms of its analytical focus on Web 2.0. In fact, he was generous in his praise of RWW and advice for me. He suggested I run a think-tank event on the future of the web, perhaps partnering with FM Publishing. He also made a feature request: provide topic and author feeds so that he could subscribe to certain topics and writers.

Om Malik and Silicon Valley lawyer Joyce Kim, his co-host on “The GigaOm Show,” an online video show on Revision3 launched in July 2007. Photo by Scott Beale / Laughing Squid.

The Web 2.0 Summit began on Wednesday, and its theme was “The Web’s edge.” This was defined as “the places where the Web is just beginning to take root: the industries, geographies, and applications that have yet to be conquered by the Web’s wide reach.” This seemed a perfect match for the type of content RWW did. We’d even done a series of posts the previous year that profiled the top web apps in many different countries—it helped solidify our reputation as the “outsider” tech blog that brought the rest of the world to Silicon Valley.

One of the young entrepreneurs I’d met back in New Zealand, Tim Norton, was also attending the summit. I’d begun chatting with him in 2006, and we’d met up in Wellington that year. He was currently building a software-as-a-service startup called PlanHQ and was in the valley drumming up interest from VCs and other influencers.

Tim was a barrel-chested guy in his late twenties, a bit shorter than me, with a beach-going tan and dark brown hair spiked up at the front. He tended to wear tight-fitting button-down shirts—open at the collar, chest hair visible—that showed off his muscular physique. His mental attitude mirrored the work he did on the physical side, in that he affected the kind of “hustle culture” bluster that would become increasingly common in the tech industry over the coming years. This was a bit unusual for a kiwi, but I couldn’t help admiring his confidence. He had always been friendly to me and certainly wanted his startup to be covered on RWW.

When we met up at the Web 2.0 Summit, Tim had a camera crew following him around. This was for a planned reality TV series in New Zealand called StartupTV, he told me, adding that PlanHQ was one of five local startups being profiled for the show. He’d already managed to get an on-camera interview with Tim O’Reilly in the hallways, so he was buzzing when we met. We did a quick interview about RWW and my involvement in the Web 2.0 scene over the past several years.

Still from a video at Web 2.0 Summit 2007 of Tim interviewing me. You can view the video on veoh.com

The following year I was invited to join another TV show Tim was involved in: an elimination-type reality show simply called Startup, which was modeled on American Idol. I was one of three judges, and we taped the whole first series in Auckland throughout 2008. Unfortunately, the show never came out. Tim and I stayed in contact for several more years, but I lost touch with him after then. Later, he would finally get the startup success he so craved with a video-creation product called 90 Seconds.

Later that week I ran into another future master of hustle culture. Thirty-one-year-old Gary Vaynerchuk was a relatively new entrepreneur and video blogger with a wine e-commerce startup called Wine Library. He’d started a YouTube show called Wine Library TV the previous year and had reached out to me in April 2007 to inquire about a sponsor ad on RWW. “I am an outside the box thinker,” he wrote in an email. “I am sure most wine video blogs wouldn’t advertise on your site, but I am a little different.” I finally managed to confirm the deal in late June, so his ad went up in July and ran until the end of September. When I met him in October, he was no longer a sponsor.

Still from a GaryVee YouTube video from October 2007.

We were at the Ignite event on Tuesday evening, at the trendy DNA Lounge on Eleventh Street, when Gary sidled up to me. He was wearing blue jeans and a burgundy T-shirt with the Wine Library TV name and logo on it. He was about my height or just under, had short black hair, and was well tanned. That evening he looked tired, with rings around his eyes and a five o’clock shadow. But he was still as energetic as his reputation suggested. We talked about his sponsorship stint with RWW; he said it really helped establish him in the Web 2.0 scene. He effusively praised my blog for a couple more sentences, then he told me about his ambitions for his startup—he wanted to be a billionaire, and he wanted to buy the New York Jets! The only other person I’d met with this kind of blustery charisma was Jason Calacanis, also a New Yorker.

I didn’t immediately understand why Gary wanted to make a name for himself in our little web scene. After all, he was already on his way to mainstream stardom, with profiles in the Wall Street Journal and Time magazine over the past year. He’d even appeared on Late Night with Conan O’Brien in August (he’d asked me to blog and tweet about it at the time). But hearing his broad New Jersey accent that evening at the nightclub, telling me about his outsized ambition, and then seeing him yuck it up later that night with Digg’s Kevin Rose (the glamour boy of Web 2.0), I began to understand what he wanted. His goal was to be a Silicon Valley insider; it would become a part of the persona he was selling to mainstream media. The scrappy video blogger from New Jersey, the son of Russian-immigrant parents who went west to Silicon Valley and made his fortune. A Jay Gatsby success story for the internet age.

GaryVee the month I met him, October 2007; photo by Erik Kastner.

A decade later, when he was a big social media star and a poster boy for hustle culture, he wrote a blog post claiming that “30 was the year I decided that I was going to become GaryVee.” From that time on, he wrote, he was “going to live my life in the pursuit of my ambition.” I’d met him early on in that story arc, when he was still ingratiating himself into the insider networks of Silicon Valley. That was why he’d advertised on Read/WriteWeb in 2007—it helped legitimize him in the tech industry.

I never managed to convince Gary to resume his sponsorship of RWW, but not for lack of trying—I sent a bunch of emails in the months following that meeting. But he’d already gotten what he wanted from me and was on to bigger things. Hustle culture would come to dominate Silicon Valley over the following years, most notoriously with the San Francisco and New York “tech bros” of the 2010s. Hustling wasn’t in my nature, though, due to my congenital low self-esteem.

In any case, I was about to learn that there were more important things in life than money and power.

Lead image: The MySpace party during the 2007 Web 2.0 Summit; from left to right: Prashant Agarwal, me, Sean Ammirati; photo by Brian Solis.

This post is part of my serialized book, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley’s Web 2.0 Revolution. View table of contents.

Next up: 025. Stress 2.0: Health Problems & Web Server Issues

You're reading Cybercultural, an internet history newsletter. Subscribe for free, or purchase a premium subscription. Your support for this indie publication would be greatly appreciated.