The Enshittocene: How the Internet Got Worse in the 2010s

The 2010s was a period of the internet colonized by platforms, which caused 'enshittification' of web products. Users and developers both suffered, but are fighting back now through the decentralized web.

What followed Web 2.0 was not Web 3.0 (or Web3 for that matter), but a degraded version of the internet. Maybe we should call it Web -1.0, but a more scatological term has taken hold instead: enshittification. It describes a period, roughly during the 2010s, when internet platform companies like Facebook, Twitter and Apple purposefully made their online products less user friendly, more difficult for developers to build on, and more prone to disrupting online publishers. Here are three examples:

- Over time, Facebook’s news feed has become less and less under the control of users. Now, opaque algorithms decide which items to put in your feed and whether (for example) your timeline posts with links will be properly circulated. This has a major impact on publishers, whose work is often devalued in Facebook’s feed through algorithmic choices completely outside of their control.

- Twitter started out as an open development platform — or at least that’s how it was talked about by some of its own VCs. But starting around 2012, Twitter betrayed the many developers who had built products on its APIs; sometimes even entire businesses. After shutting out developers, the third-party app ecosystem around Twitter shrivelled, which resulted in less features and functionality for users. And that was before Elon Musk took over!

- Apple does not allow external browser engines on its iOS devices, meaning that its own browser engine — WebKit — has an effective monopoly over iOS. This put a damper on third-party developers hoping to build sophisticated web applications for iOS, because some of the functionality available in (for example) Google Chrome isn’t available in Apple's Safari browser. It’s a more subtle form of enshittification, but over time it’s meant there has been less competition for iOS apps (which Apple gets a cut of if they are premium apps), which in turn means less app choice for users.

What Happened to the Web 2.0 Renaissance?

If you have read my serialised memoir, you might think Web 2.0 was a glorious period for the internet. And it was! During Web 2.0, roughly 2004-2012, we saw a renaissance of the ideals of the decentralised web. The likes of Facebook and Twitter promoted developer platforms and encouraged third-party apps to build on them. So in the first decade of this century, users and third-party developers seemed to be paramount.

However, in the quest for constant user growth and attendant increase in revenue, during the 2010s the successful Web 2.0 companies started to make choices that weren’t in the best interests of users (or developers). Cory Doctorow, who coined the word 'enshittification', described it as a kind of unvirtuous cycle:

“Here is how platforms die: first, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.”

The only problem with this theory is that platforms like Facebook and Twitter refuse to die! Some even seem to get ever more powerful, like Amazon. As Doctorow noted, Amazon started out in the late-90s as a scrappy e-commerce operation that offered great value to users:

“…for many years, it operated at a loss, using its access to the capital markets to subsidize everything you bought. It sold goods below cost and shipped them below cost. It operated a clean and useful search. If you searched for a product, Amazon tried its damndest to put it at the top of the search results.”

But now, he continues, searching Amazon “doesn't produce a list of the products that most closely match your search, it brings up a list of products whose sellers have paid the most to be at the top of that search.”

Developer Enshittification

It’s not just user experience that has suffered from platform power. Even the programming tools that developers use have been enshittified.

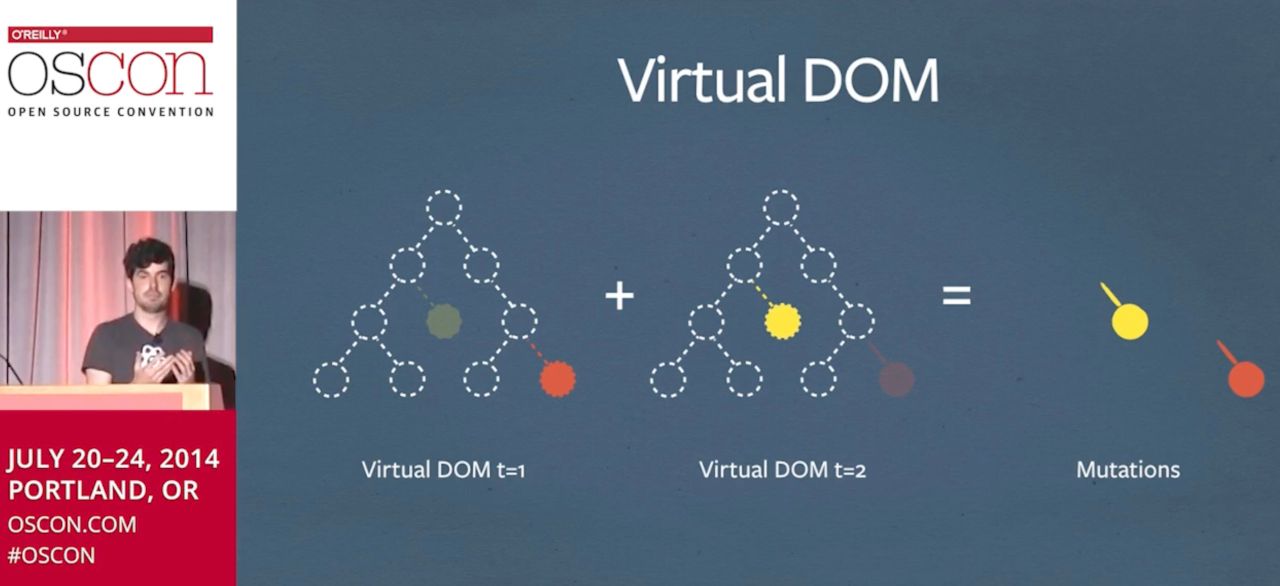

In 2014, Facebook developer Christopher Chedeau gave a presentation at Oscon about a relatively new JavaScript framework called React. Its key innovation was the creation of a “virtual DOM” (the DOM — "Document Object Model" — is a programming interface that allows JavaScript to interact with and manipulate the structure, content, and style of an HTML document).

As Chedeau explained, React gives you two “virtual” copies of the DOM — a before and after for each interaction — from which you run a “diffing” process to establish what exactly has changed. React then applies those changes to the actual DOM — meaning only a portion of the DOM is changed, with the rest of it staying as-is. That, in turn, means that only a portion of the webpage needs to be re-rendered for the end user.

If that sounds complex for developers, it is. But it was a revolutionary method of developing web apps and was especially suited to large applications where data changed a lot (like Facebook). Influential web developers took note, and adoption of React grew after 2014.

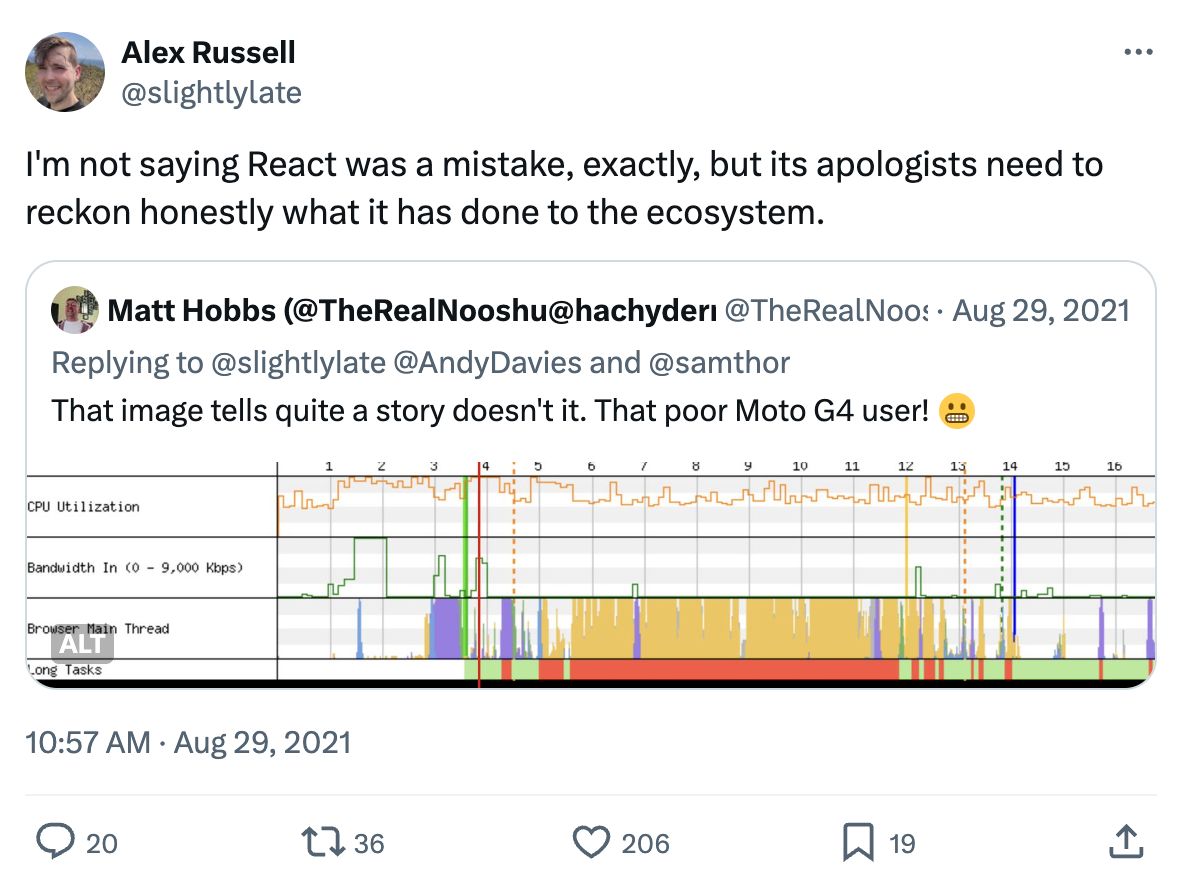

Despite its popularity, however, it didn’t take long for complaints to start rolling in about React. By the end of 2015, some developers were complaining of React “fatigue” because of the steep learning curve. More importantly, there was growing dissatisfaction with the heavy load that React-based web apps put on browsers. This is due to the large amount of JavaScript shipped to the end user, which means performance issues for many users.

According to Alex Russell from the Microsoft Edge browser team, “sites continue to send more script than is reasonable for 80+% of the world’s users, widening the gap between the haves and the have-nots.” Russell calls this “an ethical crisis for frontend” and puts the blame squarely on React and the frameworks that utilize it.

In other words, React — which was introduced to the world by Facebook — has enshittified the web development world.

Decentralized Web: The Rebel Alliance

The Enshittocene as an internet era ran from the early 2010s through to the early 2020s, at which point the generative AI era took over (although some would argue that AI is further evidence of enshittification). Regardless of timeframe, the Enshittocene represents the inverse of the renaissance that was Web 2.0. Whereas Web 2.0 promised that a thousand flowers would bloom, in the form of web applications and user-generated content, what ended up happening was the opposite: a handful of internet platforms became dominant and throttled innovation.

Far from flowers blooming in an open field, the 2010s saw the return of the dot-com walled gardens — except this time, the walls were erected even higher. As Bluesky founder and CEO Jay Graber said recently, "we're in this trap where users are locked in and developers are locked out."

However, there is now a concerted effort to knock those walls down again using decentralized web technology. Indeed, Bluesky is among a number of new social media apps that is trying to build an open ecosystem again. That trend was pioneered by the creators of ActivityPub, the W3C web standard for open social networking. Mastodon is the biggest app built on ActivityPub, but there is hope that a bunch of different "fediverse" apps will emerge to challenge centralized incumbants — Lemmy is a copy of Reddit, PeerTube is a YouTube clone, PixelFed is Flickr 3.0, and so on.

A resistance has formed among developers and indie publishers, and "users" who have rebelled against the centralized status quo and want to reclaim their online identities. It's a new world for those who have chosen to leave the Enshittocene behind them. Won't you join us?

p.s. in the Cybercultural header, you'll see the icons of Mastodon and Bluesky. Click one or both of those links to connect with me on the decentralized web.

Lead image: annie pm on Unsplash

You're reading Cybercultural, an internet history website. Subscribe for free, or purchase a premium subscription. Your support for this indie publication would be greatly appreciated.