Launch of BowieNet and the First Inklings of Social Networks

When BowieNet launched in 1998, it became the default online community for David Bowie fans. It also anticipated the social networks that would emerge in the 2000s, like Facebook and Reddit.

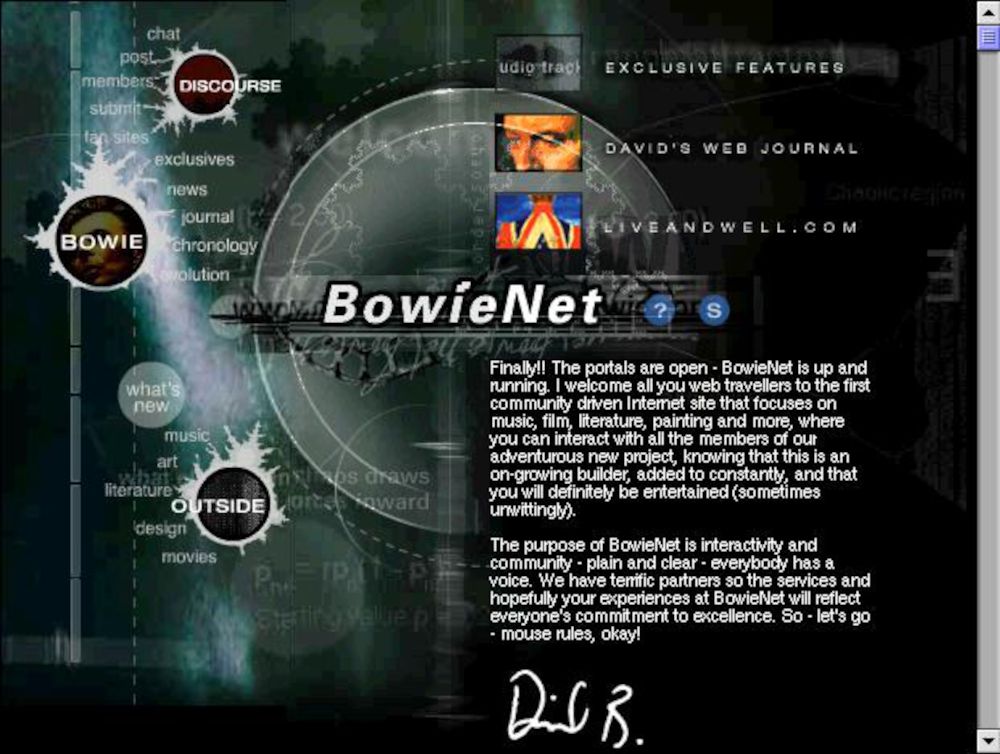

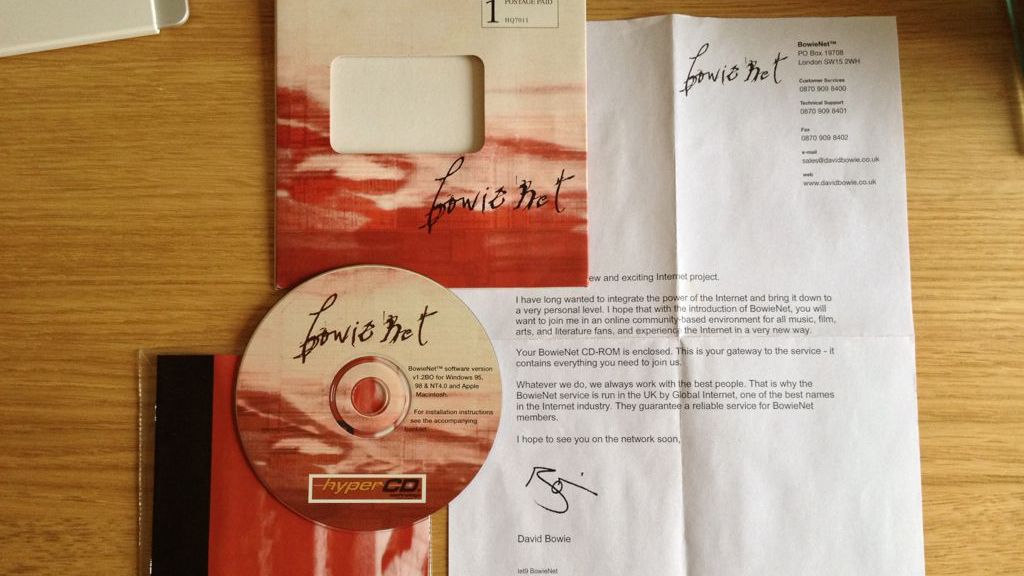

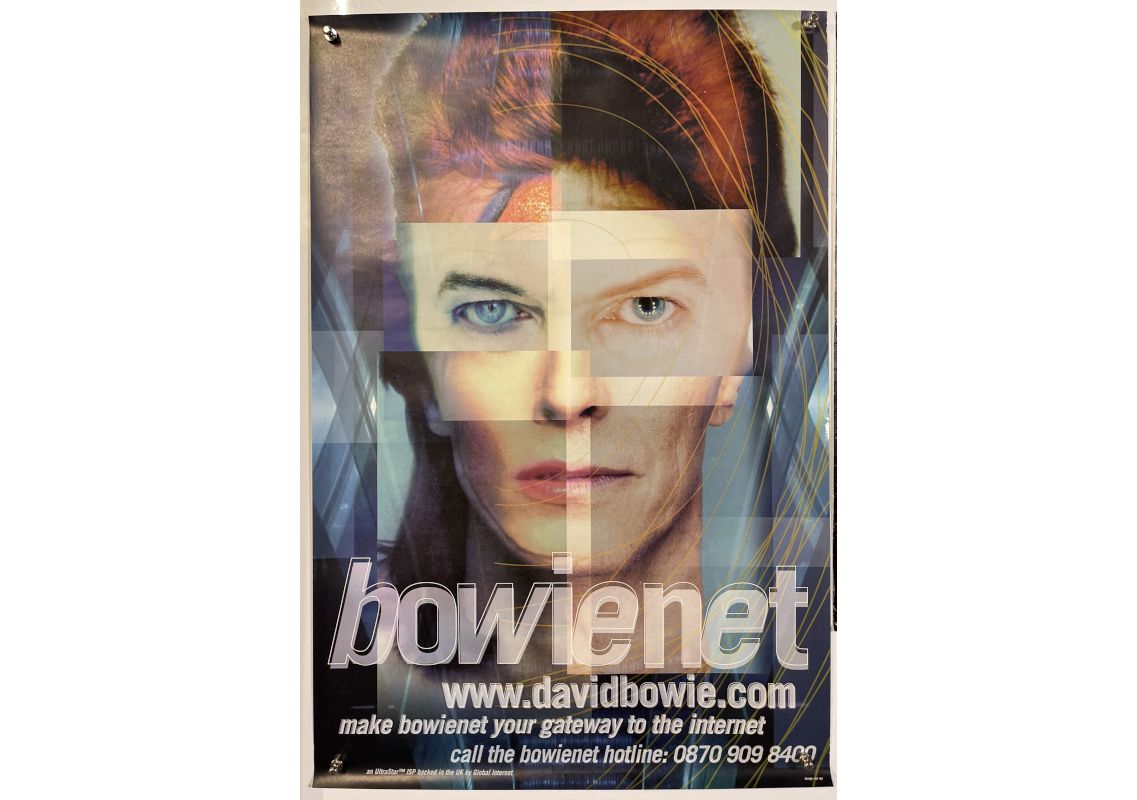

BowieNet launched as an ISP in North America on September 1, 1998 for $19.95 per month; and if you lived elsewhere, as a “premium content” service for $5.95 per month. If you had visited davidbowie.com on that day, you’d have been greeted by these words from the man himself:

“I welcome all you web travellers to the first community driven Internet site that focuses on music, film, literature, painting and more, where you can interact with all the members of our adventurous new project, knowing that this is an on-growing builder, added to constantly, and that you will definitely be entertained (sometimes unwittingly).”

Bowie added, “The purpose of BowieNet is interactivity and community — plain and clear — everybody has a voice.”

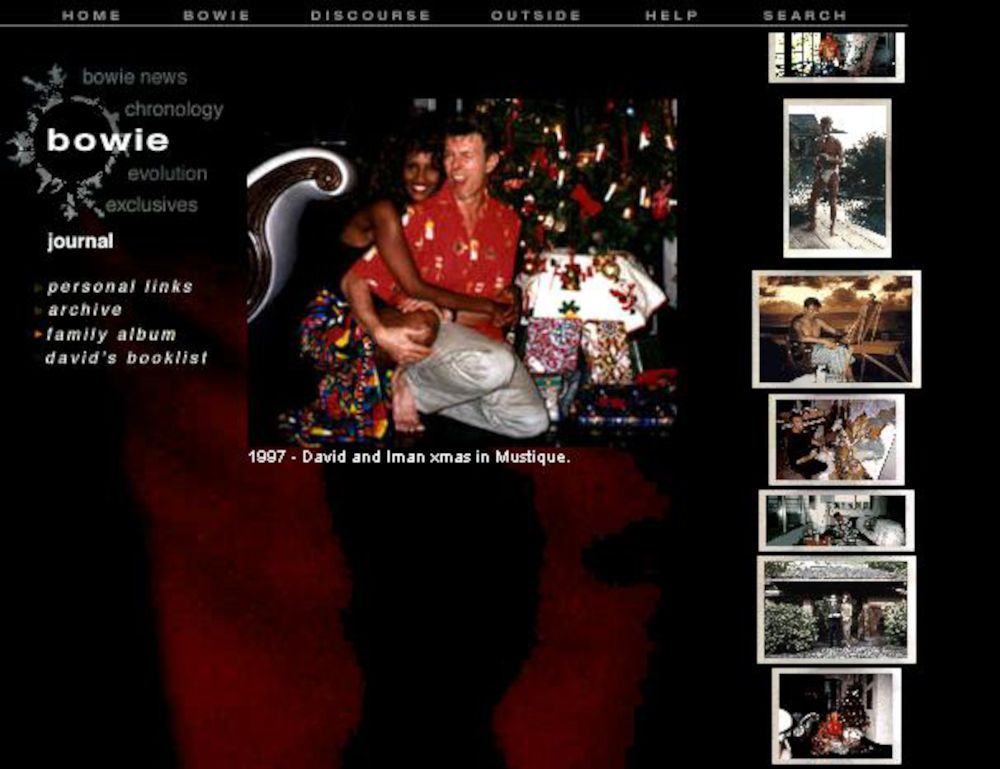

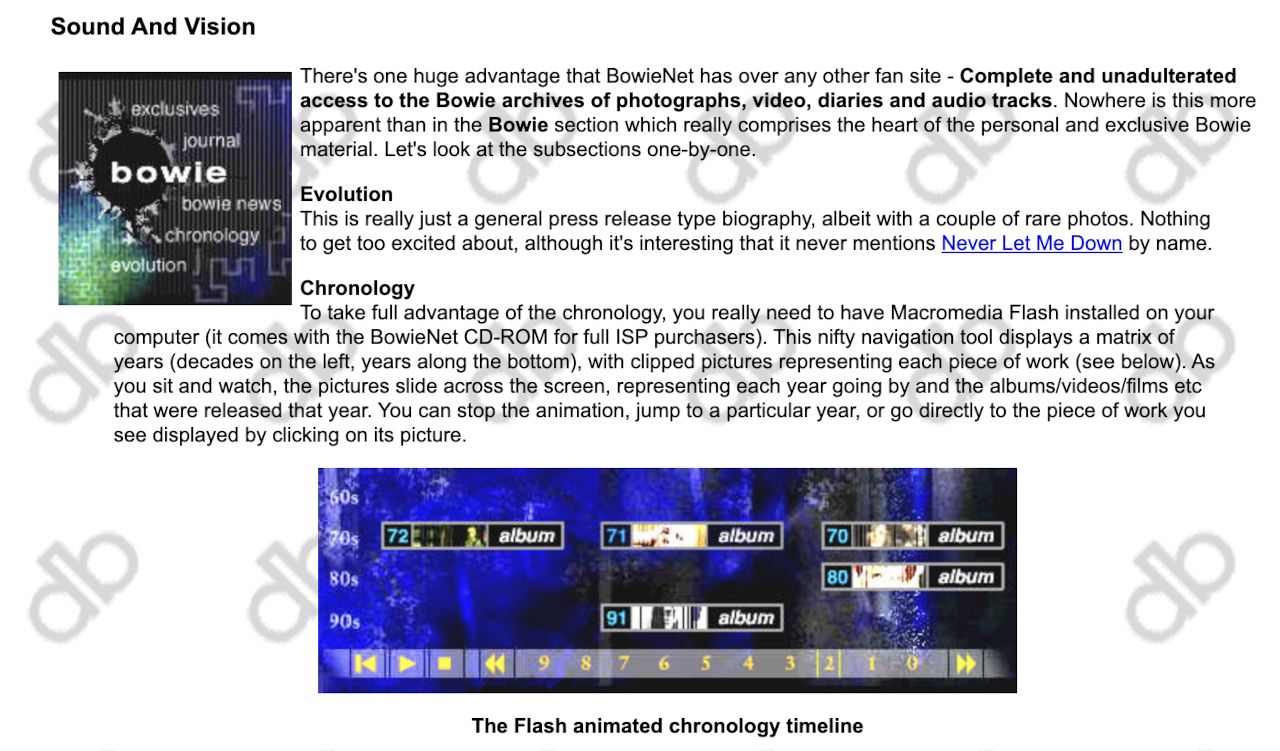

According to the official announcement, the premium content on BowieNet included “his complete music catalogue, all of which has been encoded for online listening,” an online journal with “David's thoughts and ideas,” a news section, and an “exclusives” section with things like concert footage, unreleased music tracks, and photos from "David's private collection."

New users were also promised a “revolutionary” internet-based contest (to be announced in mid-September), a video chat with Bowie at the end of September, and a “3-D chat” environment called BowieWorld in mid-October.

Despite the multimedia promises, on launch day the new Bowie portal wasn’t that different from what the best fan sites already supplied. In a review dated 9 September 1998, The Scotsman called BowieNet a “heavily-glorified fan site,” but also noted the site’s ambition to be an online community — “Interactivity and community are the buzz-words repeated mantra-like throughout the public pages.” In another review, Metroactive magazine described BowieNet as “an attractive but not exactly mind-blowing assortment of biographical material, video and audio clips and chat areas where Bowie fans can meet and converse.”

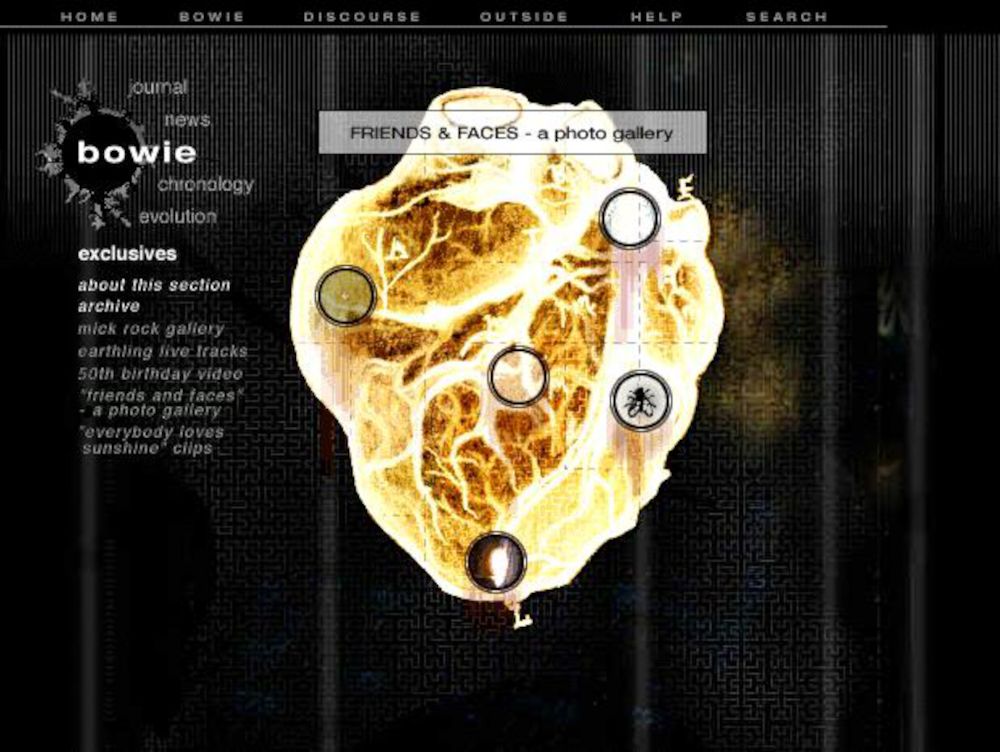

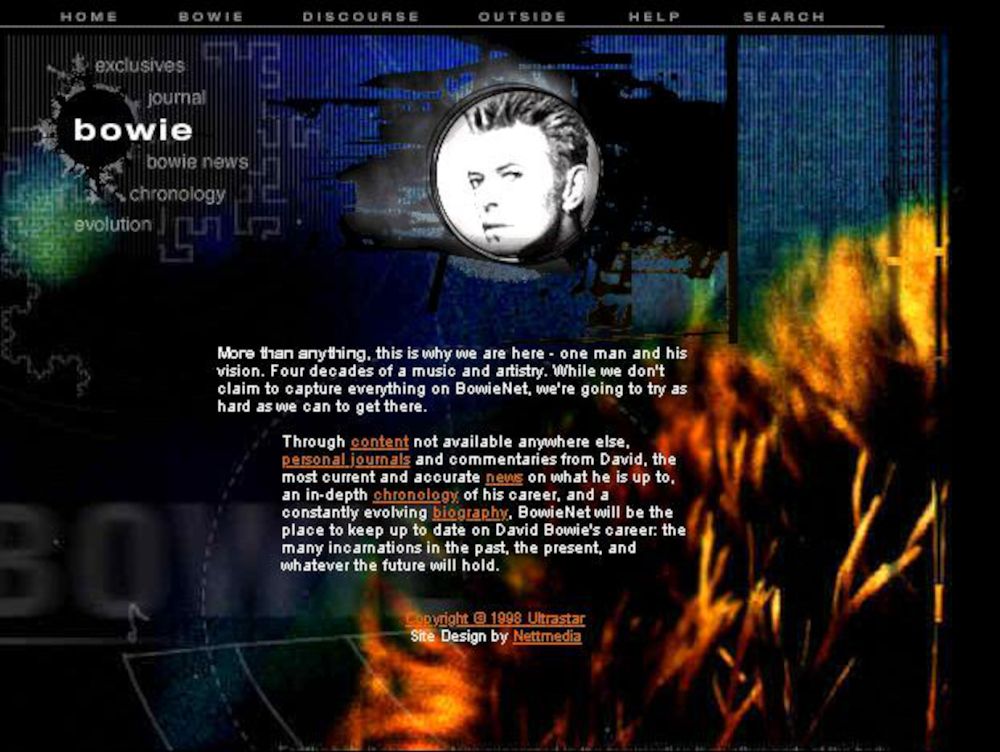

BowieNet Design

Evan Torrie from fan site Teenage Wildlife signed up for the premium content version of BowieNet on the morning of its launch. The design impressed him — “No gray backgrounds or Times 12 fonts here!”

Indeed, the new site's background was a muddy mix of dark greens, blues and black, mixed with swirls of red and yellow — with white text throughout. It was a marked change from the monochrome design of Bowie's website in 1997. Torrie noted that the new design “combines seamless [HTML] frames with dark, fractal-inspired and human body-part backgrounds to give a futuristic, chaotic look and feel.”

Bowie himself explained later that his Outside album was an inspiration for the design of BowieNet. “I wanted the look of it based primarily on the kind of deconstructed look I had on the album Outside in 1994 — working on the idea of broken graphics and that kind of feel.”

BowieNet was ambitious from a multimedia perspective too, with plenty of images, videos, Flash animations (the navigation buttons were “a swirling Mandelbrot”), and audio on the new site. Torrie seemed appreciative, but he pointed out the downsides too:

“As with any graphics-intensive site, the initial download time can sometimes be a bit intimidating for those with slow connections, and I'd certainly recommend having at least a 28K and preferably 56K modem connection (especially since some of the RealAudio clips require more than 28Kbps for immediate streaming download). Once the graphics are cached locally by your browser, the next visit goes much faster. Those of you who are lucky enough to have cable modems or DSL won't notice a thing (apart from turning me green with envy).”

The use of frames irritated Torrie — for instance, if you searched for something on the site and clicked on a result, you would lose the “surrounding frames” (such as the site’s menu). This was a common affliction with websites of the time, since CSS layouts had yet to become popular. However, Torrie seemed mildly impressed by the portal-like features in BowieNet:

“In addition to the exclusive BowieNet content, the home page also includes links to a customizable daily news section provided by Lycos, and the music news of the day from Rolling Stone. This is obviously part of a plan to become somewhat of a web portal, where members will keep BowieNet as their home page and use it as a jumping off point in their Internet travels. To encourage this, BowieNet VPN members will also get disk space to be able to build their own web pages.”

Overall, Torrie gave BowieNet a positive review. He called it “a pretty impressive piece of work, especially the personal Bowie information which has been hidden in the vaults (and I'm sure a lot more of it will surface over the coming months).”

Community and Fan Access

Reaction amongst other Bowie fans was mixed, with some believing that BowieNet was another example of “corporate” Bowie selling out. But for many fans, BowieNet quickly became an important online community. Christine Luby was a teenager when BowieNet launched, but she found her tribe on the site — and even met her future husband. Later, in 2016, she described the impact it had on her life back in 1998:

“It was a fascinating community to be part of. We all watched live webcasts and dealt with buffering issues because it was the first thing of its kind that we had ever seen. We posted on the message boards, working hard to get “karma” points, which were essentially up votes.”

Luby added that she participated in an early contest on BowieNet.

“The winner would get a phone call from Bowie himself. I came in 17th and got a signed CD of my choice. My future husband came in second and got Bowie’s entire back catalog signed. The last I heard, the winner never got that phone call.”

So the sense of community on BowieNet was immediately palpable, but was the personal connection to Bowie himself somewhat illusory? Luby wrote that Bowie “would occasionally pop into the chat and introduce us to new music like he was just one of our friends.” But then again… “the winner never got that phone call” — and friends don’t let friends down.

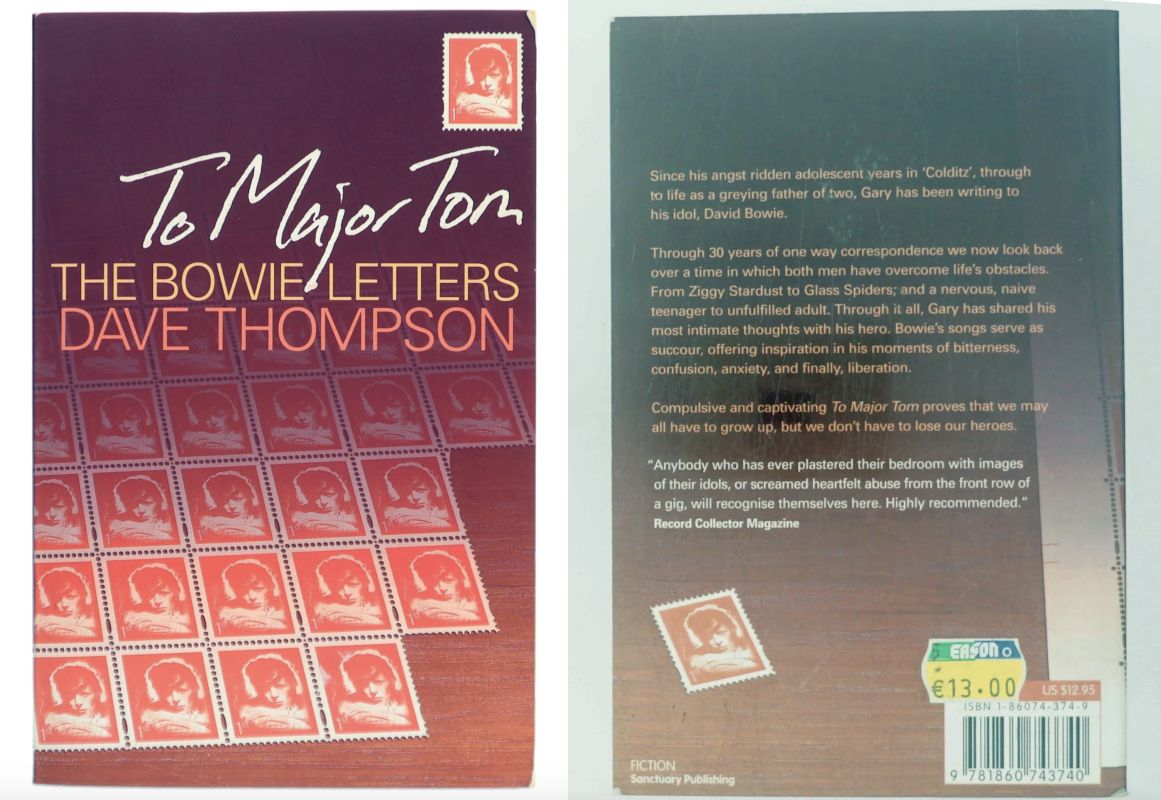

Perhaps the fan relationship aspect of BowieNet was best captured in a 2002 novel, To Major Tom: The David Bowie Letters, by Dave Thompson (who also wrote two biographies of Bowie: Moonage Daydream in 1987 and Hallo Spaceboy in 2006). The novel is structured as a series of fan letters written to Bowie by a fictional character called Gary Weightman, who had discovered Ziggy-era Bowie in 1972 as a 12-year old boy. In the introduction, Gary describes his letters as “30 years of one-way correspondence that passed between myself and David Bowie.” His sense of disappointment at never receiving an answer from his hero is only amplified with the arrival of BowieNet. Although Thompson gets the dates wrong — the first BowieNet mention is a letter dated 2 March 1998, months before it launched — his description of the artist-fan relationship rings true:

“The mistake we all make is in thinking that because you’ve made a difference to our lives, then we’ve made a difference to yours. And it’s not true, is it? Apparently, you occasionally visit the chatrooms yourself and interact with the users. But I was wondering, precisely which ‘you’ is it really?”

Gary lists out several versions of Bowie’s characters through the years, before concluding that “the only David Bowie you’re going to find on the computer is a computer image himself, a flickering 3-D graphic that has no time for the past and no vision for the future.”

As a super-fan, the fictional Gary is most interested in getting inside stories from Bowie about his unreleased songs, or insights from the great man on what will happen to all the Bowie bootlegs that have accumulated over the years. That’s what he really wants as a fan — he doesn’t even want to be Bowie’s friend, because he understands from decades of unanswered letters that it’s just not feasible.

In a following letter, this one dated 31 October 1998, Gary has finally come to terms with BowieNet and now enjoys it for what it is. “Funny thing about the Internet — you spend years denouncing it, then one day you get sucked in…” He admits that “there are a few places I habitually check out” on BowieNet, “and a lot that I’ve clicked on once.” That sounds like how many of us treat social media sites like Facebook or Reddit these days.

For many real-life fans, though, just being in proximity to Bowie — even if only virtually — was enough. “It felt good, just to think that Bowie might just read your posts,” wrote Sarah Atkinson in 2018, in response to a post on the official Bowie Facebook Page celebrating the twentieth anniversary of BowieNet.

While Bowie himself was a regular, if evasive, presence in the BowieNet chat rooms, the fans got to know each other well. So gradually a new community formed, larger and more expansive than those that had previously formed on the alt.fan.david-bowie newsgroup or on fan sites like Teenage Wildlife. You only have to scan the comments of that 20th anniversary Facebook post to see what BowieNet meant to many fans. Two of them had this sweet exchange:

Ray Garcia: Blackout80, present!

Paula Hightower: hello Ray - squeakie here 😉

Ray Garcia: Oh wow! It’s been a long time! How’s life?

Paula Hightower: Good!! you?

Ray then proceeds to tell his life story, post-BowieNet, to Paula, who responds in kind (“Congrats on finding love and raising a family!”). And while I’m not sure if Blackout80 and squeakie ever revealed their real names back in 1998, it doesn’t matter — they were connected by their Bowie fandom and an online community run by their hero, and their life stories became interesting to each other as a result. It wasn’t quite social networking, in the way that Facebook would do it in the 2000s. But it was slightly more personal than your typical newsgroup or chatroom in 1998.

Socializing on the Web

Something new was happening on the web at this time — people were spending more time on the internet and the web’s communication tools had become more diverse and just plain better. Social networks and social media hadn’t yet emerged, but web-based communities were prevalent and were encouraging deeper connections than, say, a Usenet forum. Instant messaging was also blossoming in 1998, thanks to products like ICQ (which was bought by AOL in June 1998) and Yahoo Messenger (which launched in March 1998 as Yahoo! Pager). BowieNet contributed to this change in the zeitgeist, with its active message boards and occasional group chats with Bowie himself.

In an academic paper published in February 2001, sociologist Barry Wellman discussed the emergence of “computerized communication networks” in the late 90s:

“The human use of these technologies is creating and sustaining community ties. These ties have transformed cyberspace into cyberplaces, as people connect online with kindred spirits, engage in supportive and sociable relationships with them, and imbue their activity online with meaning, belonging and identity.”

From the get-go, BowieNet became a “cyberplace” where kindred souls connected. Was this part of the birth of internet culture? What was really happening here? As he so often did, Bowie managed to capture in a song the sense that culture was changing — but not always in good ways. Even more remarkably, in this case the song was co-written by a fan, via the Internet.

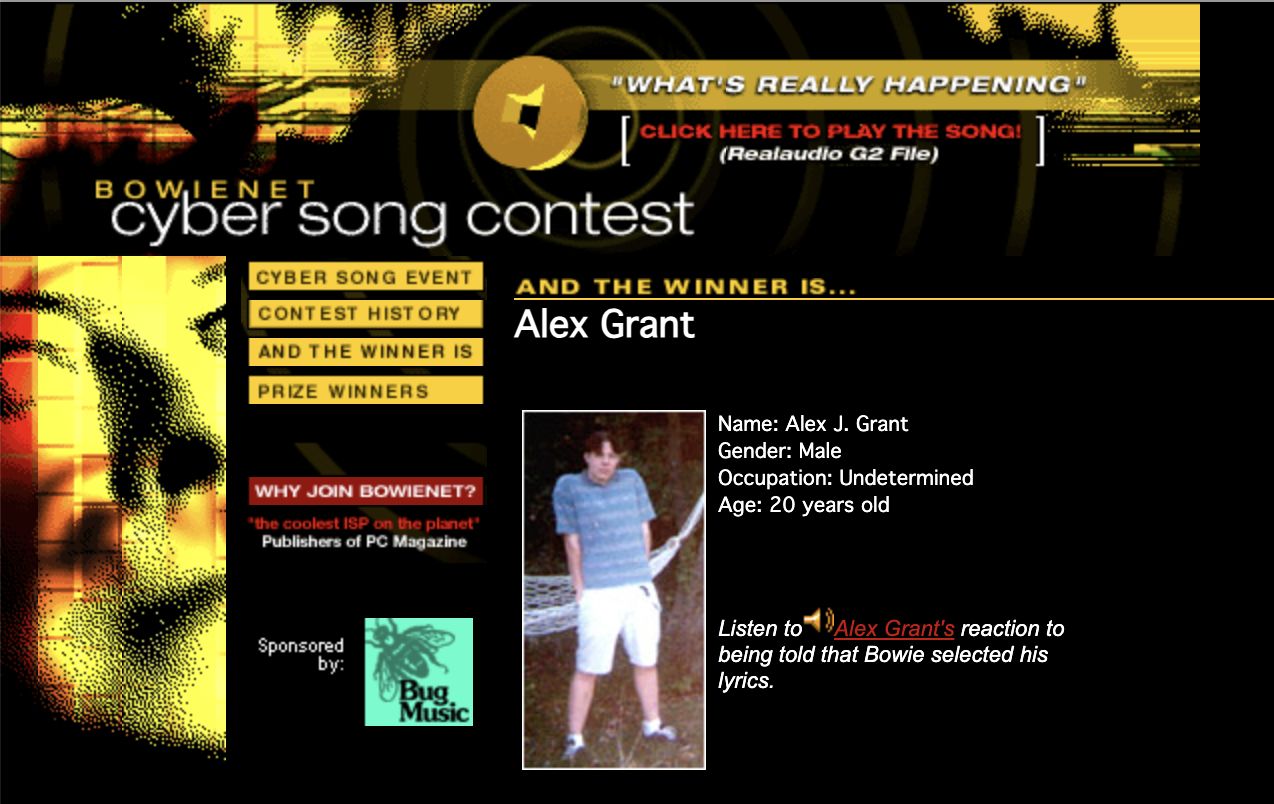

At the end of October, the big online contest promised at the launch of BowieNet was finally announced. It was a songwriting contest where fans were invited to “compete to become co-writer on one of his new songs, entitled What's Really Happening.” Bowie had already written the music and chorus for the song and contestants were asked to “submit three verses.”

The winner turned out to be a 20-year old from Ohio, Alex Grant, who got to meet Bowie as he recorded the song vocals in May 1999. In documentary footage of the encounter, Grant explained that his lyrics were kind of a meta commentary on the internet. “When I first logged on three years ago, [the Web] was this beautiful magic thing, but after a certain amount of time I was getting stuck inside of that — my whole life became the Internet,” he said. The first verse reflects this and is almost claustrophobic in tone:

Grown inside a plastic box

Micro thoughts and safety locks

Hearts become outdated clocks

Tickin' in your mind

Bowie’s chorus repeated the lines “What's really happening? What tore us apart?” Granted, that could mean anything. But I like to think it is, in one sense, about the sea change the internet was causing in the wider culture in the late 1990s. Bowie was surfing that change harder than most other musicians (although Prince and Todd Rundgren also embraced the web during this time).

Of course, in 1998 nobody truly understood “what’s really happening” with the internet — and what growing up “inside a plastic box” (a personal computer) might be doing to the generation of kids born into this new cyber world. We'd have to wait another 15-20 years for that shoe to drop.

This is part of a series of posts about BowieNet and David Bowie's website in the mid-to-late 1990s:

- David Bowie’s Early Websites, 1995–1997: Outside to Earthling

- Telling Lies: Bowie and Online Music Distribution in 1996

- BowieNet: The Inside Story of Its Creation

- Launch of BowieNet and the First Inklings of Social Networks

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.