The Age of Buffering: Video Streaming and Webcasts in 1997

During 1997, video streaming came to web browsers through plug-ins like RealVideo, VDOLive and Microsoft's NetShow. David Bowie even attempted to 'cybercast' one of his concerts that year.

Online music companies like N2K and Liquid Audio were mostly concerned with music downloads, but it was now possible to stream music in the browser — that is, have it play in real-time. By 1997, streaming was possible not just with audio, but video too. Although, this was often an unsatisfactory experience for the end user.

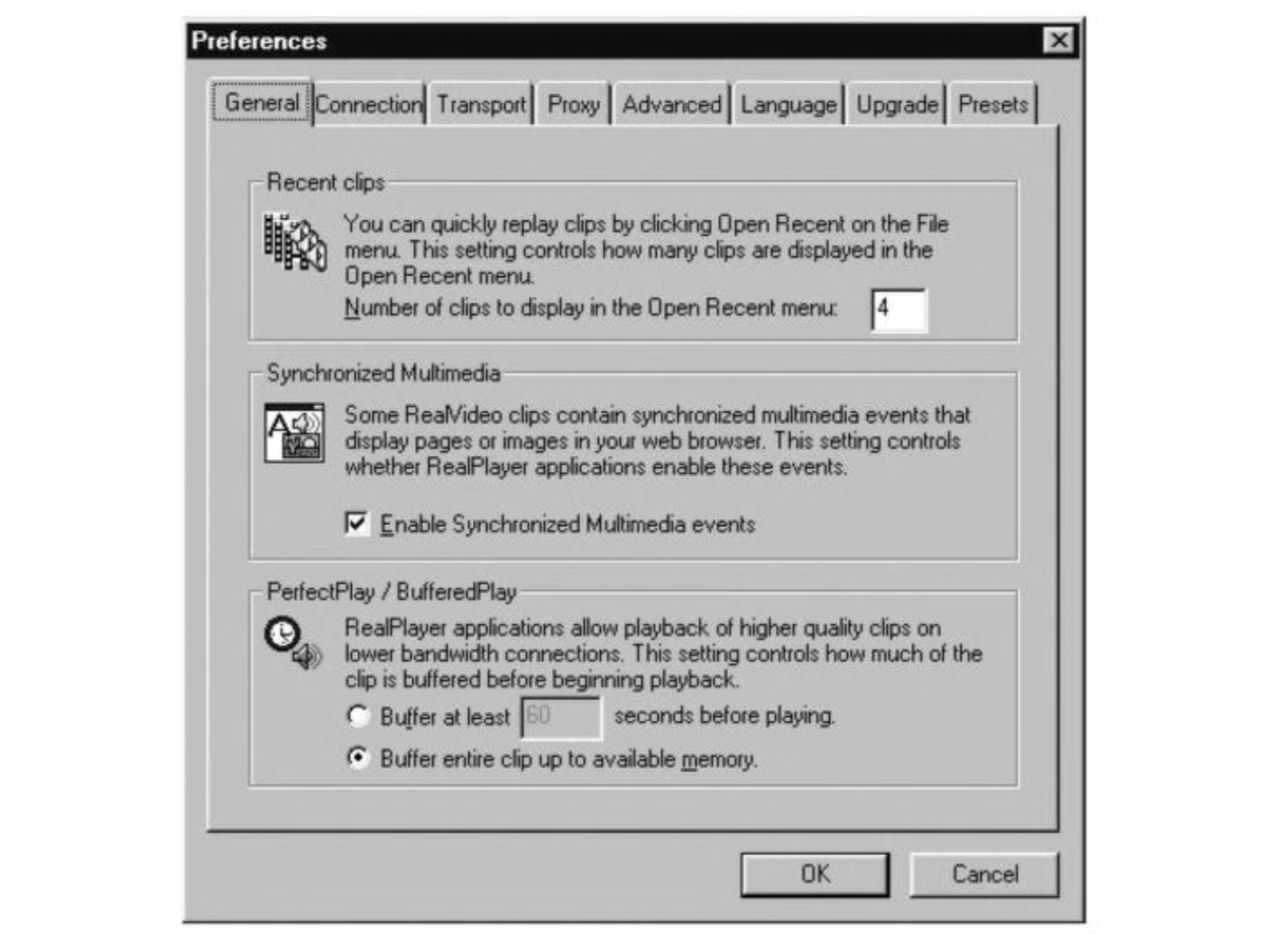

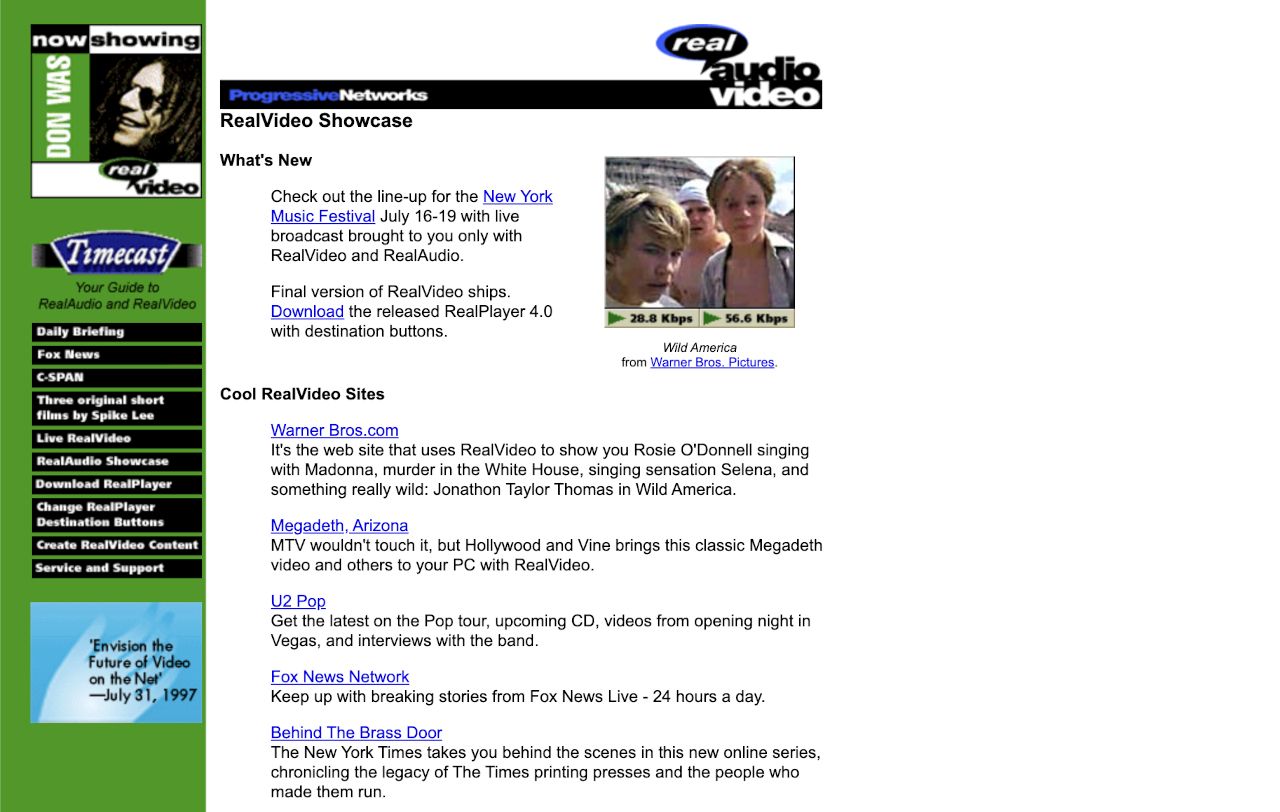

In February, Progressive Networks announced RealVideo to try and commercialize video streaming. The final version of RealVideo was released in June and included new features like “streaming thinning,” which purported to detect “poor or congested Internet connections and will dynamically adjust the video frame rate for both live and on-demand content in real-time.”

Despite Progressive Networks' promise of “always-on, all-the-time” online video, the reality was rather different when it came to “webcasting” a live event via video streaming.

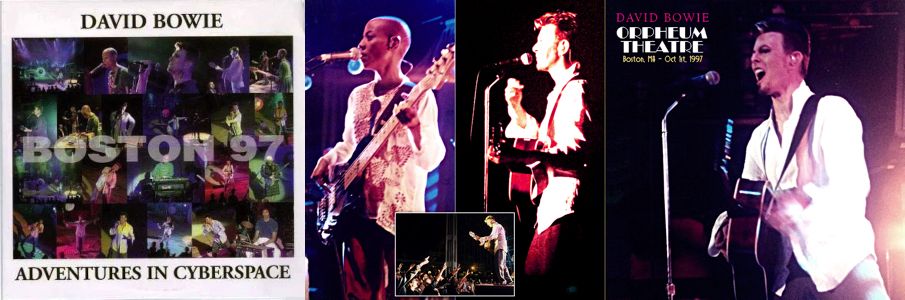

A year after the Telling Lies online release, it was announced that David Bowie would webcast — or what his people called “cybercast” — an upcoming concert in the Earthling tour. The show would be on October 1, at Boston’s Orpheum Theatre, and the technologies that would enable this were RealAudio, RealVideo, NetShow and VDOLive.

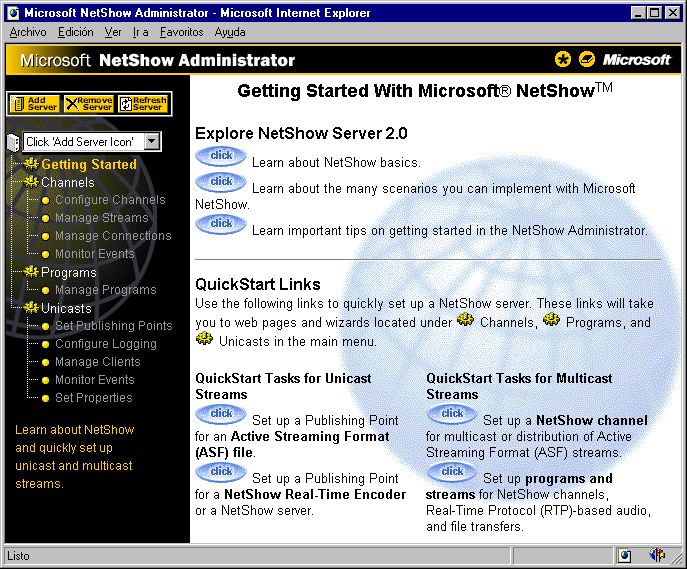

NetShow was Microsoft’s version of what Progressive Networks had pioneered. The NetShow Player (which later morphed into Windows Media Player) had been included in the release of IE4 and promised to bring “production-scale audio and video broadcasts to web application or sites.” Meanwhile, VDOnet was a small video streaming business trying to gain a foothold in the market (it would eventually be acquired by Progressive Networks the following year).

Progressive Networks was the undisputed leader in streaming multimedia, at least technically. Microsoft was the 800-pound gorilla that threatened to crush it. Perhaps fuelled by this rivalry, the hype around online video ramped up in significantly over 1997.

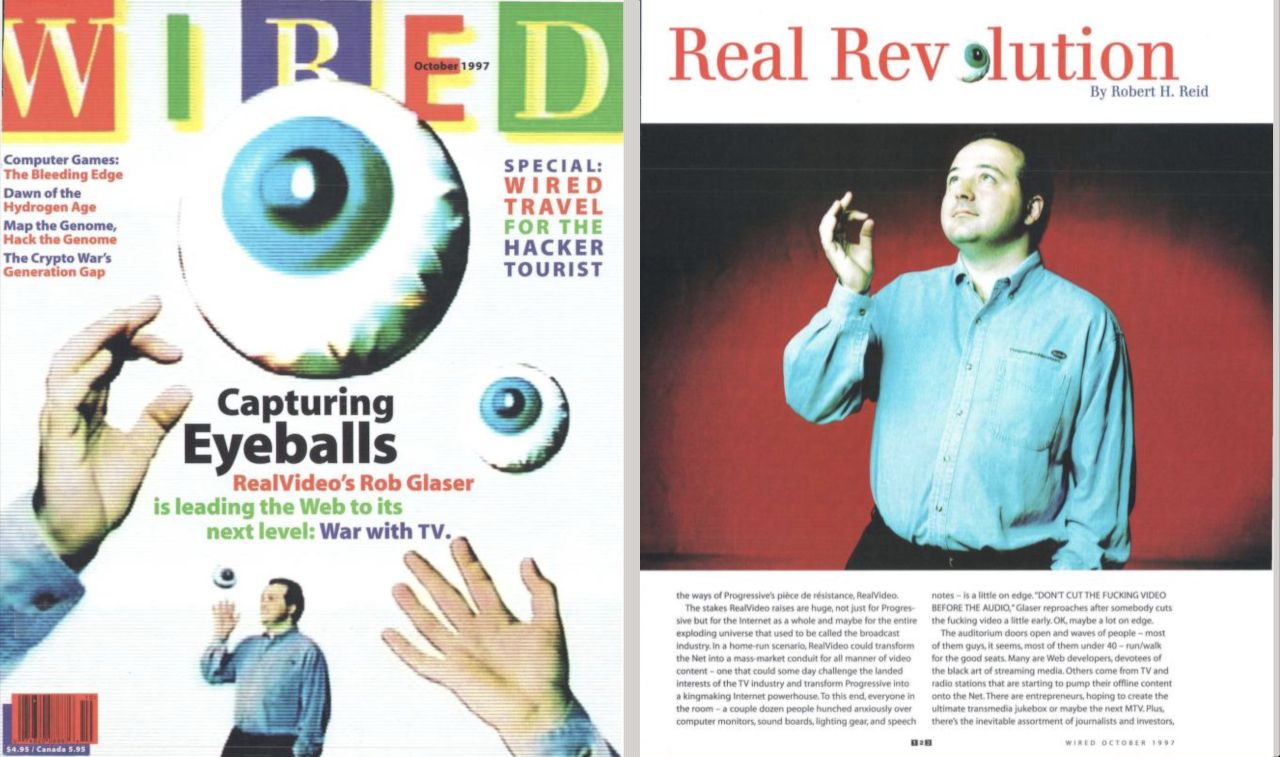

In an October 1997 profile of Progressive Networks, which rather ridiculously positioned the company as leading a “war with TV,” Wired confirmed that RealVideo was the better solution — “NetShow didn't look or sound as good as RealVideo.” But anyone who read that article and had also tried to tune into David Bowie’s concert on the web would’ve noticed a glaring disparity.

(Note: Progressive Networks changed its name to RealNetworks in September 1997, just after the Wired profile and just before the company's IPO.)

David Bowie himself was both excited and cautiously ironic as he opened his concert at Orpheum Theatre on 1 October 1997.

“We’re joined this evening on the Internet,” Bowie said to the Boston audience after the second song that evening, a rollicking version of ‘Queen Bitch.’ In his familiar lad-about-town South London accent, he then poked gentle fun at the internet. “What is an Internet? They’re getting a simul-ah…broadcast of the show tonight. Hello Internet people! Oh, there's only one of them, and he's had to bring his own camera anyway, so it's probably not really…so if you brought your PowerBooks, probably it’s not going to afford you much further enjoyment tonight.”

Despite affecting to know little about the Internet in this welcome spiel, Bowie almost certainly had an inkling that technical issues would provide an underwhelming experience for the “Internet people” tuning in. And that’s exactly what happened. Since most people were on 28.8Kbps dial-up connections (56Kbps if you were lucky), the experience of live streaming the concert proved less than ideal.

“I don't know who else saw the cybercast of tonight's Boston concert, but I did and I thought the internet version was terrible! I had all the right hardware and software to view the concert live, but both video and audio were very poor in quality,” complained a fan on the Bowie newsgroup, alt.fan.david-bowie.

The fan further noted that “all I got were garbled pictures frame-by-frame,” so the video was basically a write-off. “I at least listened in,” he added.

Even those with more than a dial-up connection were frustrated.

“I have an ethernet connection and I wasn't impressed with the cybercast at all,” wrote another fan. “I was getting like 3 frames a second at the best times. I can't imagine how bad it would've been like with a modem.”

If you worked for a business or were a student at a university at the time, it was possible you could get a T1 internet connection, meaning a speed of up to 1.544 Mbps (nearly thirty times faster than dial-up). If you were really lucky, you could get T5, which had a data rate of 565/697 Mbps. These were different levels of carrier systems developed by AT&T, for digital transmission of telephone calls and data over physical cables.

“I'm one of the lucky ones with a cable modem connection giving me approximately T1 speeds...the quality still sucked,” said one Bowie fan, adding that the event was “mostly unwatchable/unlistenable...shows you how wide the gap between hype and reality with this Internet media stuff.”

“I've got a T-1 connection from my university, and the quality was awful,” replied someone else. “I ended up minimizing Real Player and just listening to it.”

Even those who claimed to be on a T5 connection struggled.

“I have a T5 connection and it was still awful,” said another fan. “The audio was OK. I logged on the next morning and listened to the entire concert again but no video. This technology has to improve before they can start offering these services.”

These real-world complaints didn’t stop the hype about online video increasing. In a February 1998 article for a publication called HotList, a “members-only publication of a New England-area ISP,” Lisa M. Moore discussed the growing trend of webcasts like Bowie’s:

“There are now Webcasts every day of the week, from major acts like Bowie, U2, the Cure, and the Rolling Stones, to smaller acts like Chavez, the Squirrel Nut Zippers and the Afghan Whigs. And, although everything from poetry readings to the Hong Kong handover is being "Netcast" or "cybercast," as Webcasting is also known, popular music events are garnering the lion's share of attention.”

Much of the article amplifies the hype of webcasting, including a short interview with Nicholas Butterworth, president of an online music site called SonicNet (which, after some corporate twists and turns, eventually got acquired by MTV in May 1999). “I think there's something very magical about being able to log on to your computer and tap in to a live event that's happening thousands of miles away and have it come to you right there in your living room,” Butterworth told Moore.

It’s only near the end of the article that the key problem of limited bandwidth is mentioned. “At 28.8Kbps, streaming audio and video feeds can contain a lot of static, and the video image appears in a window only slightly larger than a postage stamp,” Moore wrote.

Bowie’s cybercast proved that video streaming technology wasn’t quite as ready for web prime time as certain articles would have you believe. It did have one positive outcome for hardcore Bowie fans, however: it made it much easier to bootleg that particular show. It is now easily found online, as a double-CD length bootleg appropriately entitled Adventures In Cyberspace.

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.