The Internet’s Impact on Culture

Marc Andreessen says the internet's impact on culture is just beginning and that it will set the culture going forward. But what does he mean by that?

“It feels like the internet’s impact on culture is just beginning. A world in which culture is based on the internet, which is what I think is happening, is just the very start. Right, ’cause it had to get universal before it could set the culture.”

Those words were spoken by Marc Andreessen, co-founder of Netscape in the Dot Com era and now co-founder of the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz. He was speaking to another internet luminary, Kevin Kelly (a co-founder of Wired magazine), on the topic of “why we should be optimistic about the future.”

I’ve been pondering what Andreessen meant, because unfortunately Kelly didn’t ask for any clarification. What did he mean by culture “based on the internet”? How can the internet “set the culture”?

Part of the problem is that Andreeseen’s VC partner, Ben Horowitz, has a new book out entitled ‘What You Do Is Who You Are: How to Create Your Business Culture.’ So when I googled “Andreessen culture,” and variations thereof, all I found was references to that book. But of course, Horowitz is using the term “culture” to mean the ethics and behaviour of a business. Not, as Andreessen used the term, to mean the arts, entertainment and media industries.

The other challenge I had in trying to tease out Andreessen’s meaning is that he no longer writes a blog, or even uses Twitter very much. As far as I can tell, he only thinks out loud in irregular conference appearances and podcast episodes. Perhaps it’s beside the point, but I do think it’s sad that one of the leading thinkers on internet technology doesn’t engage with people anymore on the internet. Or perhaps it’s just smart business, since his VC firm is in the business of finding – and funding – The Next Big Thing before anybody else.

So I’m forced to try and decipher for myself what Marc Andreessen meant when he said that “the internet’s impact on culture is just beginning” and that we’re now entering an era where “culture is based on the internet.”

Thinking about it in eras is a good approach. So let’s start by looking back at the Dot Com period, which Marc Andreessen had a big part in shaping thanks to his pioneering Mosaic and Netscape Navigator web browsers. This was when culture first had to adjust to the internet.

In music, for instance, it became common in the 90s to share digital music files publicly over the internet – often without the permission of the copyright owners. At its extreme, that led to Napster in 1999 and the rise of peer-to-peer (P2P) file sharing on a mass scale. Eventually, after vanquishing Napster and its P2P ilk through the legal system, the record labels figured out how to sell digital downloads of music. Largely thanks to Apple and its iPods and iTunes Store.

All of this happened in the Dot Com period or just after. But despite the record companies and Apple figuring out how to use the internet to sell music – in other words, successfully adjusting to the internet – not much had truly changed in the music business.

The traditional formats – singles and albums – were still largely the same. Okay, playlists had suddenly jumped in popularity, thanks to iTunes putting them front and centre in its app (in order to sell more 99c song downloads). But the artists still produced singles and albums, and then marketed them through radio promotion, music videos (back when MTV still played them) and other record label promotion. And we consumers still acquired their music – sometimes buying it, sometimes not – and added it to our “record collection.” The only difference was, increasingly our record collections were managed through software like iTunes and lived on a digital hardware device (like the iPod).

When the so-called Web 2.0 era began, roughly in 2004, music sharing became further legitimised when social networks like MySpace and then Facebook emerged. But again, not much had fundamentally changed about how the internet and the music industry mixed.

In summary, for the first twenty or so years of the Web, the music industry was at first rocked by the internet (Napster and file sharing) but then successfully adapted to it (iTunes and iPods). The internet became a legitimate distribution channel for music, with Apple cleverly inserting itself as a new middle man.

2015 was the turning point.

The advent of streaming, from Spotify and others, was the first sign that the internet might no longer be just a distribution channel for music. In fact, Spotify ended up fundamentally changing how we consume music.

With streaming and the online subscription model, by 2015 the internet had begun to shape and re-make the music business. Or as Marc Andreessen might say, set the culture.

Although like any new technological paradigm, music streaming didn’t happen suddenly in a single year. There was a build-up – and build out – of several years.

Spotify was initially launched only in Europe, starting October 2008, but it didn’t really take off as a cultural phenomenon until its US launch in July 2011. By September 2011, Spotify had doubled its paying subscribers to 2 million. By the end of 2012, it was 20 million total active users, including 5 million paying customers globally. Fast forward another couple of years and it was 60 million users, including 15 million paying, by December 2014.

As of October last year, Spotify now has 248 million monthly active users (MAUs) and 113 million subscribers, with its paid user base growing 31% year-over-year.

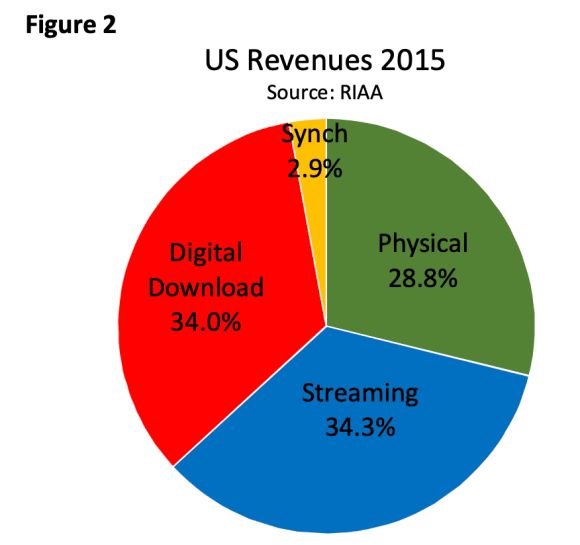

The key year though was 2015. That’s when streaming revenue surpassed both digital downloads and physical sales for the first time, according to the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).

Not coincidentally, 2015 was when Apple fully embraced the streaming era. In June of that year Apple Music launched, in the process integrating Apple’s Pandora clone iTunes Radio (which had been launched in 2013). Apple Music was modelled on Spotify, where users could stream entire albums and playlists. It was proof that Spotify’s user-controlled streaming service had won out over its main competition till that point, the internet radio service Pandora.

Incidentally, 2015 would be the last year Pandora had more active users than Spotify. As of last November, Spotify has nearly four times as many (248m vs. 63.1m). The two models are very different – with Spotify the user is in complete control of what music is played, but with Pandora the user doesn’t always control which songs are played. Pandora started out in 2005 as a “recommendation engine” for music, but by the time Spotify ramped up in the US it was clear consumers wanted to choose their own music (the on-demand model).

So streaming overtook digital downloads in 2015, which of course affected Apple’s revenue from music. But the impact of streaming on the music industry was more profound than just changing the revenue models. This was a total re-imagineering of what it means to consume music in this era.

For one thing, we no longer have to purchase music as a product – whether a CD or digital download. Indeed, purchasing music has almost become an anachronism nowadays. Most of us now simply “subscribe” to music as a service, whether through Spotify, Apple, Amazon, or some other streaming aggregator.

I used to have a CD collection of music that filled a few CD racks. Sometime in the Web 2.0 era I began copying the CDs I owned – as well as many CDs I borrowed from my local library – into iTunes. So iTunes became the home of my music collection.

But not any more.

I can’t remember the last time I bought a CD, although I’ve continued to buy the odd album on Bandcamp (a digital download store for independent artists). Right up till 2019, I had continued to import music into iTunes. Now I have even stopped doing that, because nearly everything I own – or at least, still want to listen to – is on Spotify. Although I haven’t completely abandoned iTunes, I’m more likely to fire up Spotify when I want to listen to music – whether it be at the gym, in my home office, or where ever.

We’ve seen similar evolutions play out in other cultural industries. Movies and TV are also largely consumed nowadays by subscribing to streaming services. Like Spotify in music, Netflix led the way in the streaming of video entertainment. Netflix actually launched back in the Dot Com era, as a DVD rental service. It introduced streaming in 2007, but it wasn’t until Netflix began creating its own tv shows in 2013 (starting with ‘House of Cards’) that streaming began to take off in TV and movies.

Streaming changed the way we consume television, in particular. It became common to “binge” TV shows (consume multiple episodes in one sitting), which in turn changed how TV shows were made. These days popular TV shows are serial in structure, meaning that storylines play out and interweave over an entire season – and in the bigger picture, an entire series. Prior to streaming, episodes of television tended to be self-contained stories – meaning they followed the traditional ‘beginning, middle, end’ narrative structure, over the course of a thirty or sixty minute episode. Now, a typical episode of a show like House of Cards or Mindhunter is usually unresolved at the end, which entices viewers to move straight onto the next episode (helped of course by Netflix and other streaming services automatically starting the next episode).

In the cases of both music and television, the internet has changed culture for the good. Spotify and Netflix, and their competitors, have given more people access to more cultural content than ever before. Now, whether it’s been good from the point of view of creators is another question (streaming revenues for musicians are minuscule compared to what they used to earn from CDs). But from a consumer point of view, it’s hard to argue that Spotify and Netflix have been bad for us.

One cultural sector where the internet has, I would argue, set the culture in the wrong way is book publishing. Not only are books less widely read now, since there is so much other “content” to consume via streaming and browsing your social media feeds, but there hasn’t been an equivalent internet revolution in books comparable to streaming in music and television.

The closest books have had to an internet reset was Amazon’s ebook self-publishing ecosystem combined with its Kindle e-reader, which debuted in 2007. But the Kindle hasn’t had a major technology upgrade since the Paperwhite was launched in September 2012 (there have been other models since then, like the Oasis line, but none has truly advanced the state of e-readers). And while Amazon did launch an ebook streaming service called Kindle Unlimited in 2014, it has a limited selection of books and as a result is not widely used.

More recently, the popularity of audiobooks has lifted the book industry’s fortunes a little. But overall the industry is struggling, due in large part to Amazon – which dominates book retail – not innovating enough in the internet era.

I mustn’t forget to mention two other technologies that have had a profound impact on the cultural industries over the past decade: smartphones and social media.

In the case of music, to take one example, we all use our smartphones now to listen to Spotify, Apple Music and other streaming services. We also use apps on our smartphone to control music in our houses and cars.

As for social media, it’s allowed artists and creators to communicate directly with fans. Perhaps more importantly, it’s enabled conversations to flourish based on the actual content – fans discussing the plot and characters of ‘Succession’ on Twitter, for example, or Billie Eilish using her Instagram to post stories about her music and inspirations.

As an aside, Billie Eilish – who at 18 years old was born and raised in the internet era – has deliberately crafted her music to suit the streaming era. Her Grammy winning 2019 album ‘When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go?’ has thirteen diversely styled songs, designed to be successful on a variety of Spotify playlists. Her management has also deftly used Apple and Spotify promotional opportunities to gain traction for her career.

So these are all examples of how our culture is increasingly “based on the internet.” But as Marc Andreessen alluded to, we’re just at the start of the internet-led culture.

You can bet that it won’t be traditional forms of cultural content that take us to what’s next. It will be cultural content created specifically for digital technology and the internet that will define the 2020s. Online gaming, Virtual Reality experiences, Augmented Reality and similar interactive and immersive technologies are the ones to watch this decade. In large part because they will change not only how we consume content, as streaming has done over the past decade, but the shape of content itself.

You can see it happening already with online gaming. A popular game like Fortnite is part visual world, part narrative, part software, part community. But the ‘content’ itself only exists as a unique experience for each individual user. These experiences are also partly created, on the fly, through automated software. This is an entirely different paradigm from music, television or books – which are all typically consumed as finished cultural products.

If the 2010s was a decade in which the way we consumed and talked about cultural content fundamentally changed, due largely to smartphones, streaming and social media, the coming decade will be even more revolutionary. By the end of the 2020s, cultural content will be created from – and for – the internet.

Photo by Kym Ellis on Unsplash

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.