State of Online Music in 1996: RealAudio and Rocktroplis

Over 1996, the Web became an experimental testing ground for new ways of distributing and promoting music. RealAudio, Rocktropolis, Music Boulevard and IUMA were some of the leading sites.

The Internet Underground Music Archive (IUMA) is the undoubted pioneer of online music, with its website launching at the end of 1993. But over two years later, in early 1996, IUMA was struggling to make headway using the internet as a distribution channel for music.

Download speed, or lack thereof, was still the biggest issue for online music — one nickname for the web at this time was “World Wide Wait.” Most people used dial-up Internet connections, with speeds ranging from 28.8Kbps to 33.6Kbps (56Kbps modems didn’t come onto the scene until 1997).

It wasn’t just slow downloads that drove users crazy. Internet connections were also notoriously flakey. Sometimes when you tried to download or stream an audio file, an incoming phone call would drop your internet connection and you’d have to start over again later.

Not that IUMA didn’t try to make the web a distribution medium. It had initially started out as a way for indie bands to promote their music and connect with their fans, but by 1996 audio downloads and streaming were integral parts of the site. The evolution to multimedia wasn’t easy though, as IUMA co-founder Jeff Patterson and his colleague Ryan Melcher attested in the introduction to their 1998 book Audio on the Web:

“We quickly learned a lot about the Web’s limitations. We couldn’t synch up page changes with audio, we couldn’t integrate video, and we got tons of complaints about how long it took to download songs from our site.”

MPEG audio, which at this point had the file path .mp2, was the main format for downloading music files (it was a precursor of MP3). But it required a bit of initial set-up, depending on which computer and browser you used.

For Windows users, you needed to download a “sound card” first of all. Then you needed an MPEG Audio player application in order to play the file — most likely you used the default Windows one, Windows Media Player. For Netscape Navigator browsers, by far the most popular browser in 1996, you then needed to configure your browser to play .mp2 files with your chosen MPEG Audio player.

Streaming With RealAudio

For browser users, anything interactive running in a web browser in 1996 was known as a “plug-in.” This was the term, coined by Netscape, for a small third-party web application that could be added to a web page.

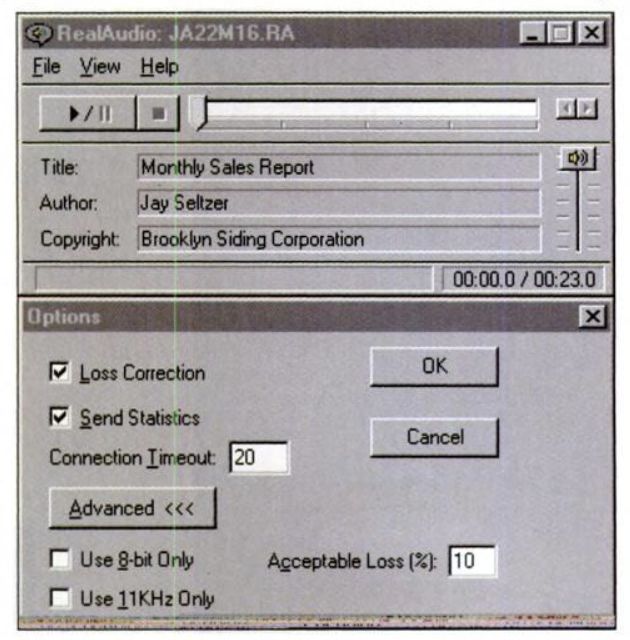

One of the earliest Netscape plug-ins was RealAudio, created by a Seattle company called Progressive Networks. IUMA made use of it on their site during 1996.

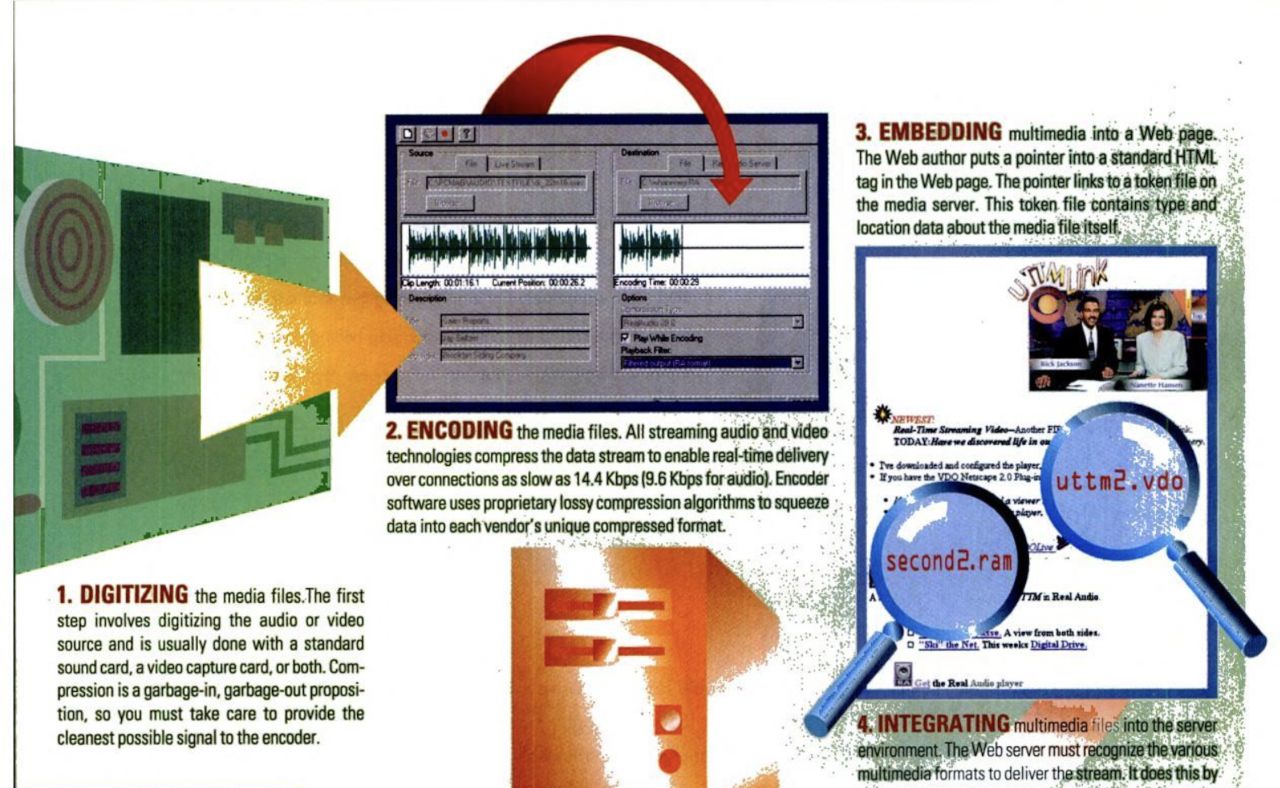

RealAudio was one of the first technologies to enable streaming audio over the Internet. It was also a product synonymous with the word “buffering,” due mainly to slow internet speeds. That aside, RealAudio was quite a remarkable technology for its time. Prior to its introduction, web users would have to download an entire audio file before playing it. That would often involve segmenting files into parts and then reassembling them after download. So audio downloads over a modem could be a painful process.

RealAudio was the first product to “stream” the audio file as it was being downloaded. It would also adjust the bitrate to fit the available bandwidth, so audio could be streamed over dial-up modems — although quality would degrade on slower connections.

When used as a plug-in to Netscape’s browser, you had to have the RealAudio software installed for the audio streams to work. It relied on a client-server architecture, with a RealAudio server required on the streaming provider's end to encode and transmit the audio streams. Some early Internet radio stations used this set-up.

By the way, RealAudio used its own proprietary format, which had a filename extension of .ra (while MP3 technology had been invented in the early 1990s, it did not become popular until the late-1990s).

Rocktroplis: Virtual Music City

Despite offering music downloads and a nascent form of streaming via RealAudio, IUMA wasn’t seen at the time as a serious threat to record labels. While it had over 800 music acts on the site, all were independent and very few had record deals — even at indie labels. By July, IUMA had reached 75,000 users. Certainly respectable, but by no means something the music industry was worried about.

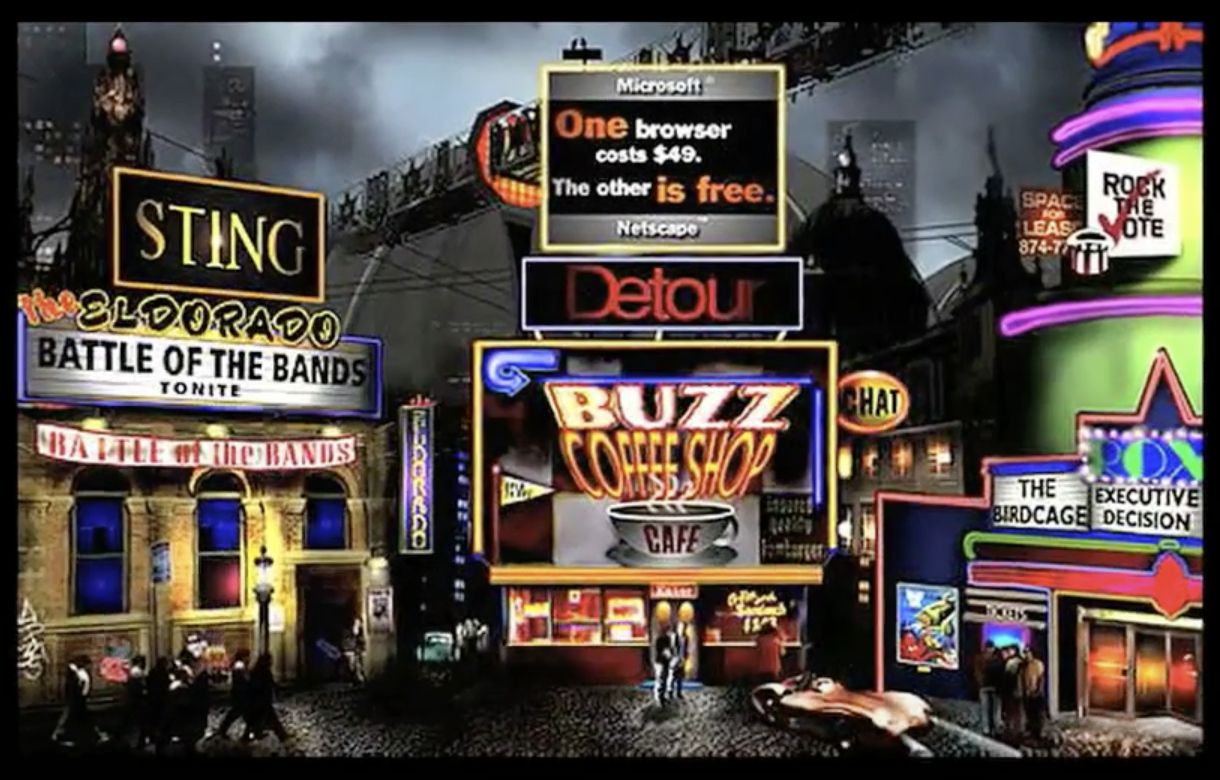

Nevertheless, the World Wide Web was becoming an experimental testing ground for new ways of distributing and promoting music. One of the more interesting websites in this regard was Rocktroplis, which Billboard called a “virtual music city” in a June 17, 1995 article about Sting (one of the first artists to feature on Rocktropolis).

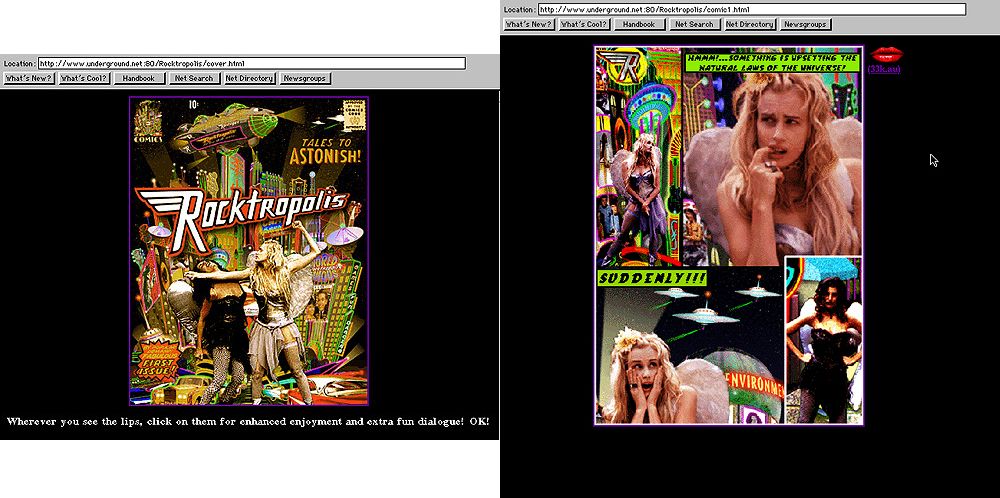

Rocktropolis had been launched in 1995 by Nick Turner, a former rock musician. As Turner said at a panel entitled “Creating Entertainment Online,” recorded on July 25, 1996 and later broadcast on C-SPAN, the goal for Rocktropolis was “creating a place, as opposed to a site with a logo at the top and the HTML text underneath it.”

The early version of the site is lost to time, but screenshots suggest a more garish version of GeoCities. A virtual Darryl Hannah ushered users into the site via the landing page, and then you’d see a cityscape with multiple alleyways and billboards crammed into the scene — each seemingly with a different color scheme and font.

Contemporary reviews seemed to appreciate the site’s content, but the overt commercialism was off-putting. In its August 21, 1995 edition, People magazine noted that the site “hasn't struck the right balance between content and commercialism: for every area with valuable info, there's another peddling T-shirts and CDs.” In an article published December 29, 1995, Entertainment Weekly wrote approvingly that Rocktropolis “spotlights new releases with full-bore Web gimmickry.”

Over 1996, Rocktropolis doubled down on the web gimmickry. In its edition dated 16 March, 1996, Billboard reported that Rocktropolis had “considerably updated its music site,” which now required Netscape Navigator 2.0 to view and utilised RealAudio, Shockwave, Xing’s Streamworks (an audio and video streaming service), and Java. In its August 1996 edition, Wired wrote that “Rocktropolis is graphically gorgeous (read: slooooww) and filled with tantalizing, explorable nooks and crannies.”

Music Business on the Web

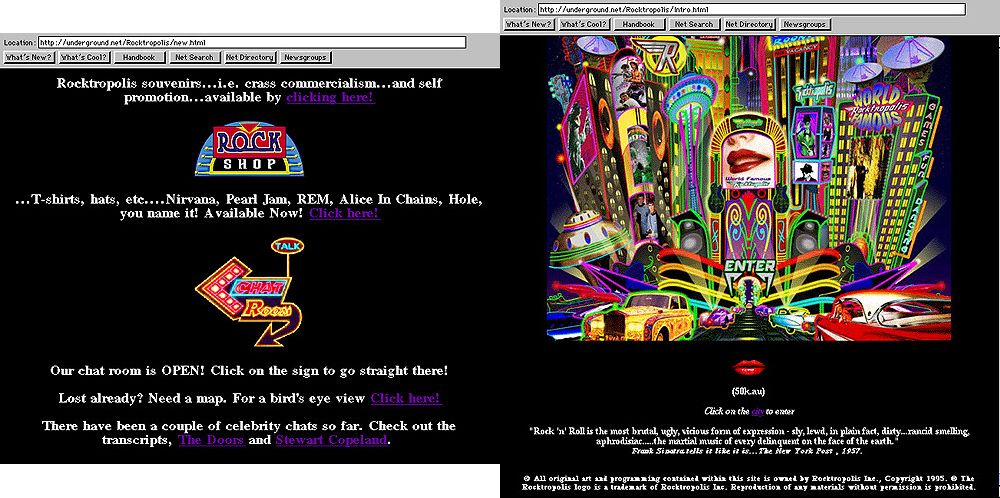

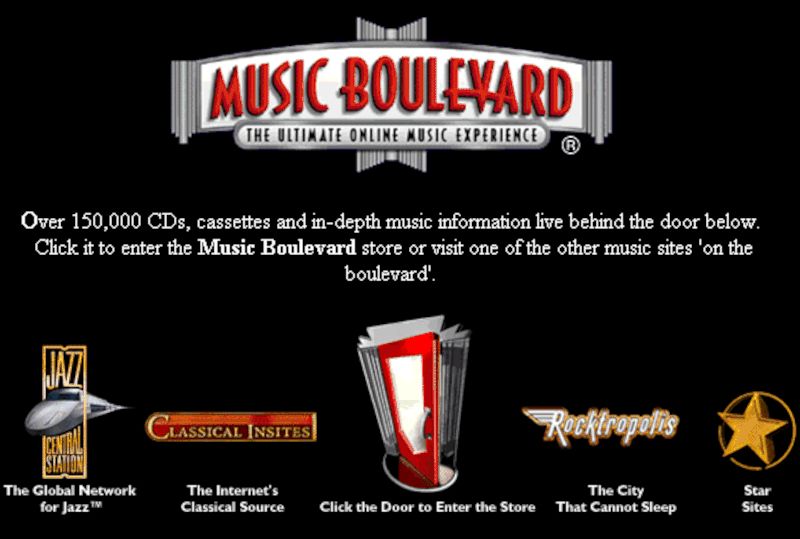

Along with the technological progress of the Rocktropolis website, there was an attendant increase in commercialism. In the July 1996 panel, Turner noted that he had merged Rocktropolis with N2K — the company that had created the first version of David Bowie’s website. The intention was for N2K to help with selling CDs online, along with “developing the whole business area of the site.”

This was a point in the web’s evolution where revenue models were beginning to form. Turner partnered with N2K partly to help him get advertisers. But he noted that although advertisers were interested in the web, they were “incredibly confused right now.” Rocktropolis was doing banner advertising, like many other sites at the time, but he said they were exploring “product placement and that kind of stuff within the virtual city.” Through N2K, Rocktropolis was introduced to Music Boulevard, a leading online CD retailer that N2K had merged with in February. So the plan was to sell CDs and other merchandise on the site, although Turner noted that “people are still being educated [that] it is relatively safe to use their credit cards online.”

As for the music itself, Turner suggested in July 1996 that users were accustomed to waiting several minutes or more for downloads to complete, and actually wanted more music or video files to download. “They're happy to wait three or four minutes — or sometimes if we have video, even 20 minutes, they’ll go make a cup of coffee or something, come back and then they have something on their hard drive forever.”

However, Turner admitted that Rocktropolis users found it difficult to navigate the site and that the city metaphor didn’t entirely work. “It is frustrating for the user,” he said. “We were hoping that the user would be intuitive and just keep continue to explore and explore and explore. But we've now found that we have to present them with the information and lead them to where we want them to go. And I think that's a factor of bandwidth as well.”

A further frustration for Turner was that despite the launch of Netscape Navigator 2.0 in early 1996, many of its users were still using older technology — which meant they couldn’t experience the latest version of Rocktropolis, with its RealAudio streaming, Shockwave videos, and so forth. He said there were “still probably 50% of people with Netscape 1.1, or AOL users, or whatever, who can't see what we do.”

Tech Advances

Despite the practical struggles of sites like IUMA and Rocktropolis, online music technology continued to improve in the second half of 1996.

Of particular note was the release of RealAudio 3.0 in September 1996, which allowed sites to offer "stereo sound at 28.8 [Kbps] and near CD-quality sound at higher bandwidths." Rob Glaser, chairman and CEO of the company, trumpeted the 3.0 release as marking "the beginning of the next era in Internet multimedia broadcasting." For once, the hype was justified, because RealAudio 3.0 did indeed usher in the streaming era on the internet. Progressive Networks can legitimately be viewed today as the grandparent of today’s streaming giants, such as Spotify and Netflix.

Being able to stream music was a big win for the IUMA, which boasted on its homepage that you could “enjoy our artists in real-time with RealPlayer.” David Bowie’s record label, Virgin Records, promoted Real Audio 3.0 on its website as a way “to hear dramatically improved sound,” noting that “28.8+ users can enjoy stereo.”

It’s strange to think that streaming a song in stereo was so revolutionary back then, but that was the state of the art in online media circa 1996.

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.