Netscape in 1994: The Rise of the Webuloids

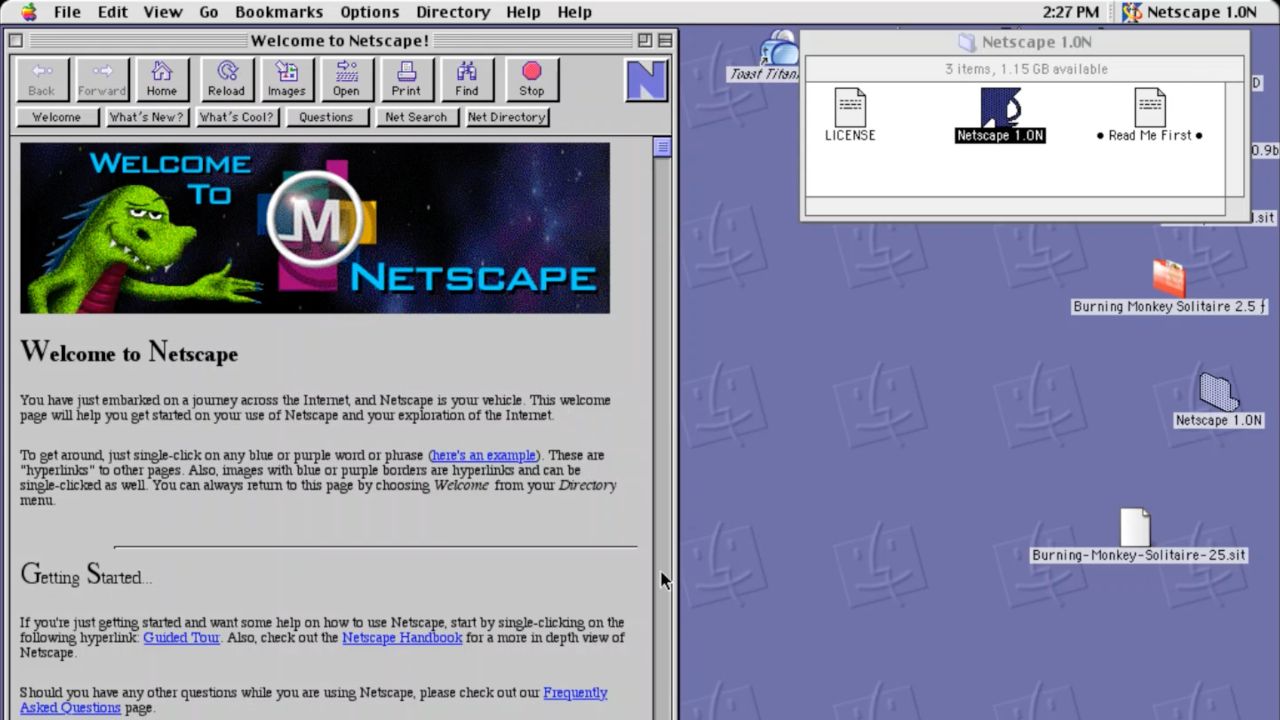

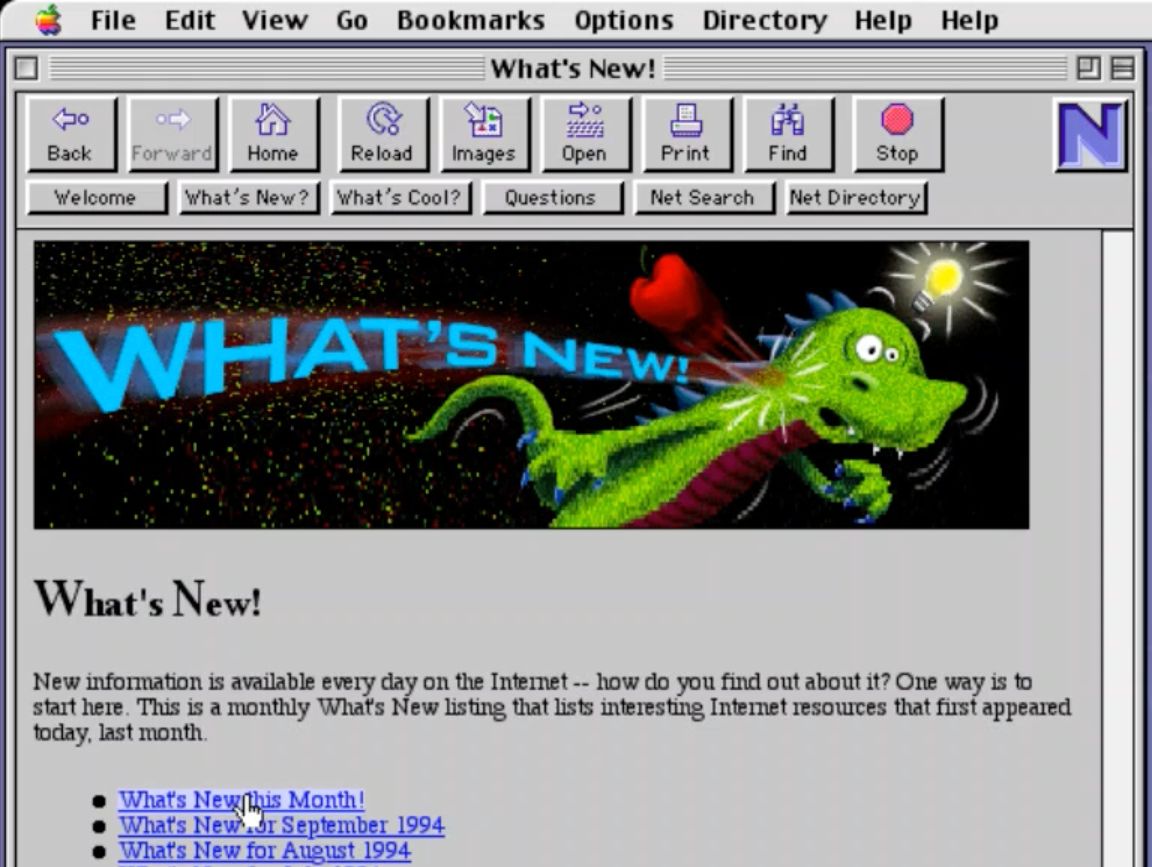

By the time Netscape Navigator was released in December 1994, the World Wide Web was beginning to overcome bandwidth restrictions and live up to its potential as a multimedia portal to the internet.

Netscape was founded in 1994 on the premise of bringing multimedia to the internet via a web browser. The initial focus was on managing basic multimedia elements — particularly images, but also sound — in an age of super slow modems.

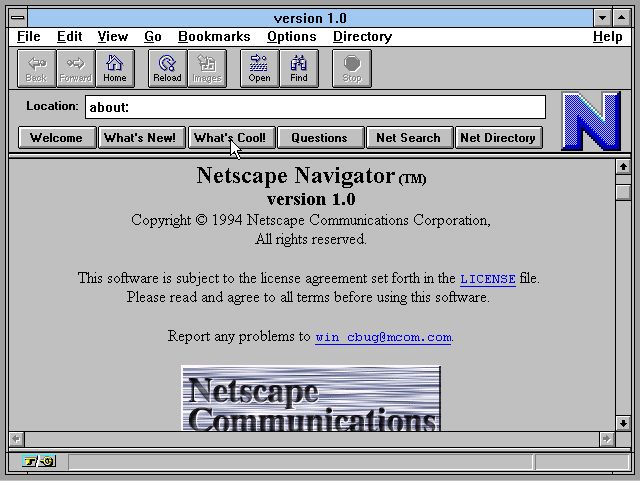

The burden of loading images was so great in these early days, that when Jim Clark and Marc Andreessen released the 1.0 version of their browser in December, they’d added an option to turn off the automatic loading of images. If a user did this, small icons were placed “in the position on the page where an image would otherwise be,” according to a manual from that time. Many early web users will remember seeing those little image icons. You often had to hesitate before clicking on them, in order to make a quick mental calculation of how much time and bandwidth you had available!

In the 1.0 announcement of Netscape Navigator (previously called Mosaic Netscape), it was said that Navigator was “optimized to run smoothly over 14.4 kilobit/second modems as well as higher bandwidth lines, delivering performance as much as ten times that of other network browsers.”

The “as well as higher bandwidth lines” bit was due to the appearance of the first 28.8 kilobit/second modems onto the market in late-1994 — potentially offering speeds twice as fast as the previous generation. The international standard for 28.8 Kbps (V.34) had been ratified in September 1994, but it took months for this to filter through to computer retailers. As late as March 1995, a Washington Post article about modems stated that 14.4 Kbps modems were “today's most popular models” — although it added that “manufacturers are now pushing hard to get you interested in 28.8 kbps modems.”

Even if you had a new 28.8 Kbps modem by the end of 1994, there was no guarantee your phone line would be capable of reaching the top speeds. It was common for large file downloads requested on a 28 Kbps modem to run at an average of between 1 and 6 Kbps. So the true speed of data transfer in late 1994, when Netscape Navigator 1.0 was released, was often only about one fifth of the advertised one. These problems were exacerbated at peak times of Internet usage, such as the early evening.

On top of all this, there just weren’t many Internet Service Providers (ISPs) in 1994 — so for most people, the only way to get on the Internet was through a walled garden provider like CompuServe, Prodigy or AOL.

Regardless of internet access issues or the technical limitations of web surfing in 1994, Clark and Andreessen were betting that the World Wide Web would become the future of media consumption. The question was: how long would it take for that future to arrive?

Internet in a Box

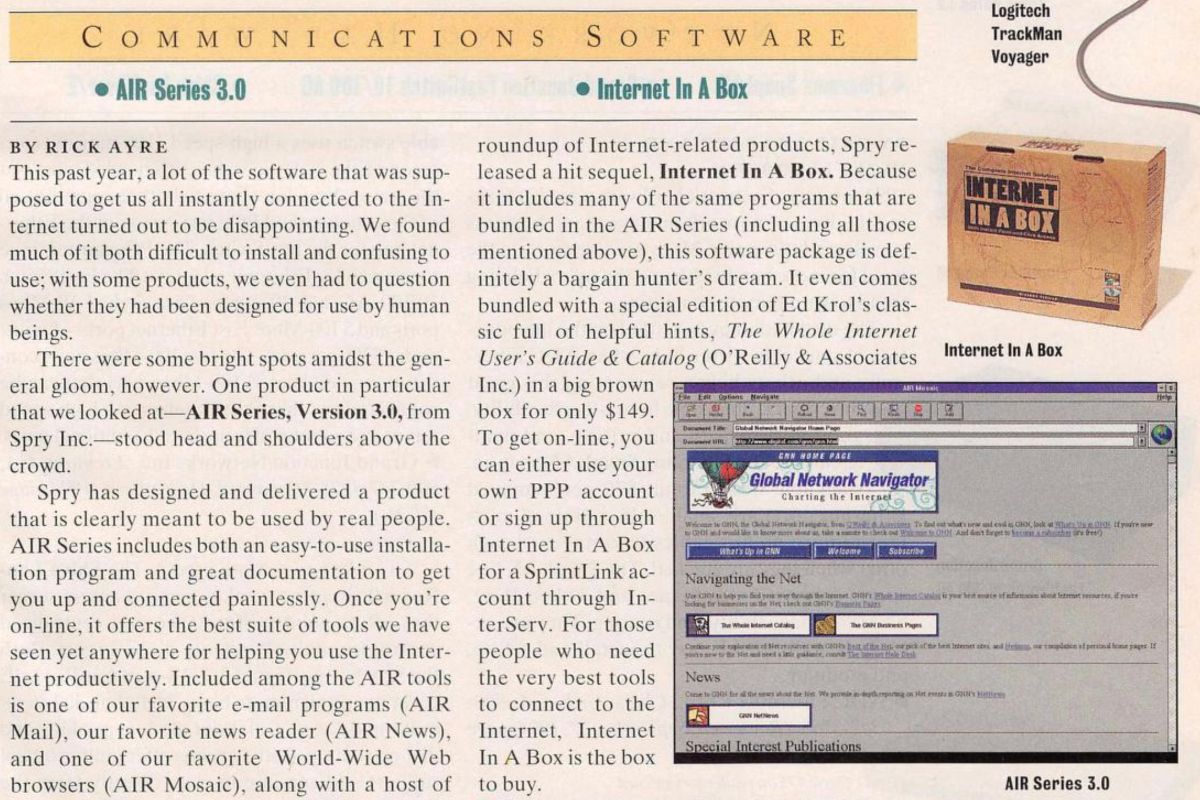

In its “Best Products of 1994” Christmas issue, PC Magazine claimed that “this was the year CD-ROMs exploded.” But clearly what hadn’t exploded yet was the Internet, which was barely mentioned in the 380-page issue. Amongst the pages of reviews of printers, accounting software and wireless LANS, there was not a single note about Netscape Navigator.

However, Mosaic was briefly mentioned when PC Magazine named two products from a company called Spry as its best “communications software” of 1994. Spry was in fact the first company to licence the Mosaic browser from the University of Illinois’ NCSA division, and its software bundles — one of which was called “Internet In A Box” — included a version of Mosaic (called AirMosaic).

But the box metaphor for the Internet was analog thinking. As its very name implied, Netscape was already thinking about itself as a front end interface for information and commerce networks — starting with the World Wide Web, but also the Internet more broadly. Indeed, in Netscape’s December 1994 press release announcing Navigator, the company said it would encompass “other global networks” as well. The implication was clear: whichever information networks became dominant, Netscape aimed to be the default user interface.

It’s easy to forget now, but Netscape’s strategy to be a software interface to multimedia flew in the face of the prevailing theory of the Internet at the time: that it would eventually “converge” into one dominant physical interface (a box, if you will). Most people thought the winner would be the box sitting in the corner of everybody’s lounge — cable television.

In an interview in early 1995, Andreessen was asked, “do you see the physical interfaces for all these services — TV, videophone service, personal computers, video games and the like — converging towards a single box?” He replied that convergence was one model, but that “interconnection is probably the right model.”

Crucially, interconnection was a software model — and Andreessen wasn’t thinking about connecting boxes, he was thinking about connecting people.

From ROMbloids to Webuloids

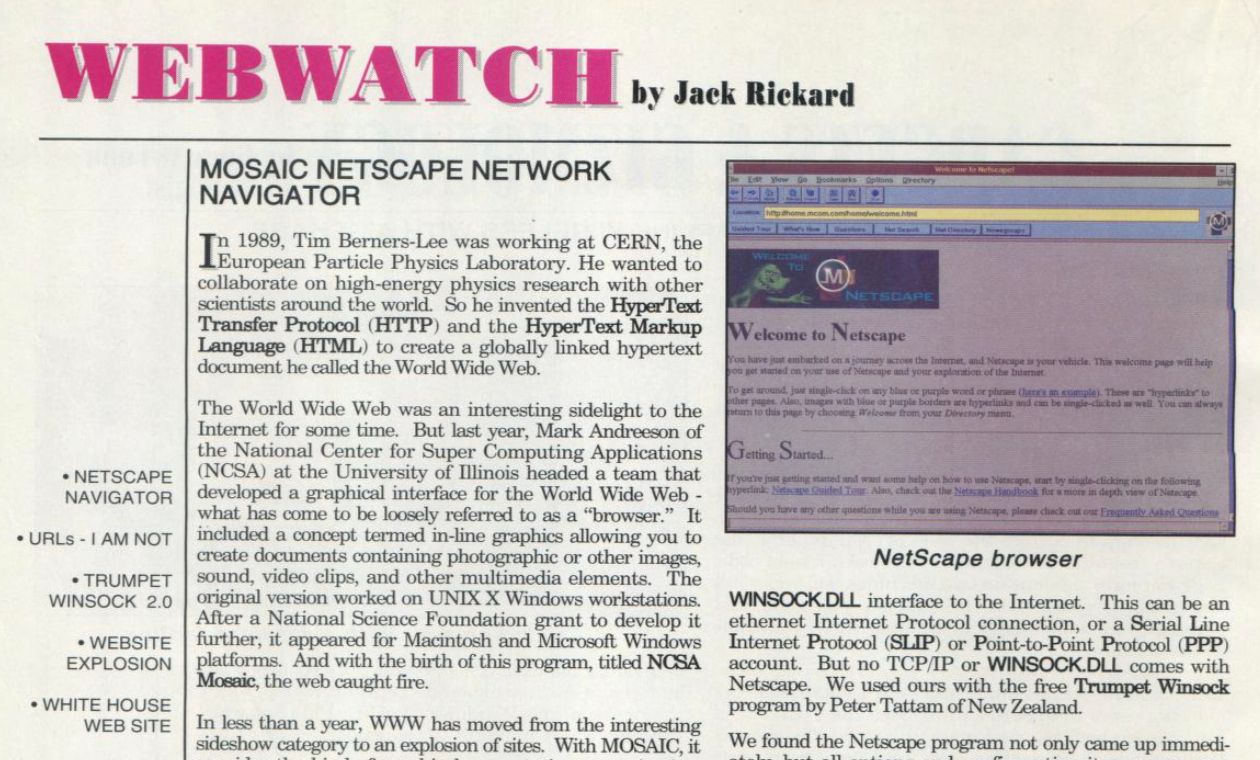

In the December 1994 edition of Boardwatch, a magazine devoted to the online Bulletin Board Systems of the 1980s and 1990s, editor Jack Rickard declared that he was a newly converted “webuloid” — perhaps a wordplay on David Bowie’s “peoploids” from the 1974 album, Diamond Dogs.

Boardwatch had covered the World Wide Web “in numerous past issues,” but Rickard admitted that he’d previously been “a closet skeptic about WWW.” He listed out several reasons for that: the web was too focused on information and not enough on communication between people, it was a “bandwidth hog,” there wasn’t enough compelling software, and not enough people were even on the internet at that time (Rickard estimated that maybe one million people could connect to the web “if they really wanted to”).

However, by December, Rickard had come around — and it was because of Netscape's browser. “Mosaic served as a catalyst and the web is flashing into something very different to what it was,” he wrote.

What seems to have engaged Rickard most of all was what Marc Andreessen had been trying to proselytise over 1994: that Mosaic/Navigator was a graphical interface to interconnect with various internet systems, which in turn allowed for more people to connect with each other. In trying to get across his new-found enthusiasm for web browsing, Rickard reverted to capitalisation. He was practically shouting hallelujahs.

“USENET newsgroups in Mosaic? Why not? Why not e-mail? Why not Internet Relay Chat? That you can NOW read in Newsgroups and actually click on HTTP Universal Resource Locators embedded IN messages and BE there is illustrative of how this is really something DIFFERENT.”

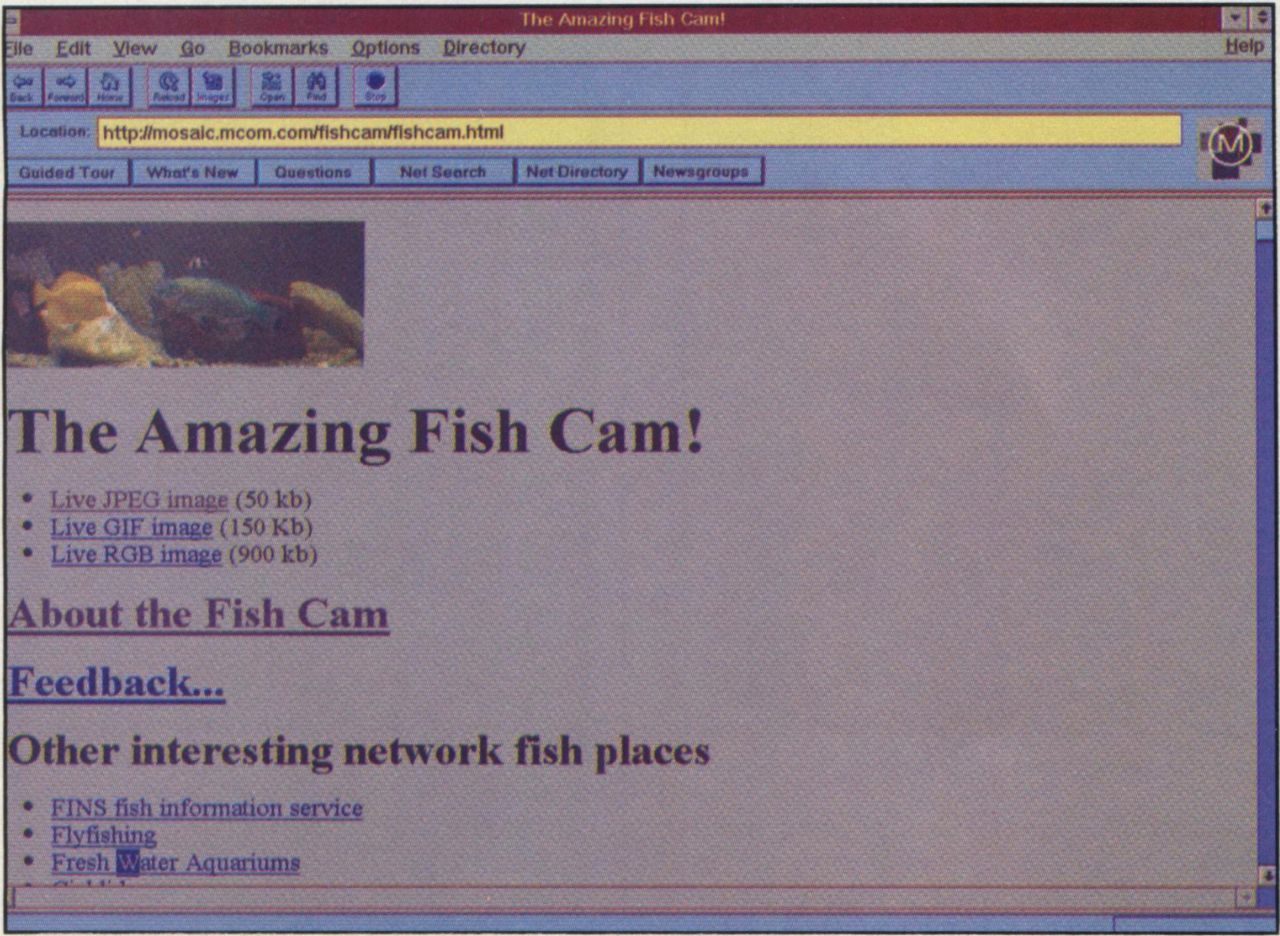

In his review of Navigator later in the issue, Rickard highlighted Netscape’s “Fish Cam” project, which offered almost real-time glimpses into Netscape employee Lou Montulli’s office fish tank. Every minute a digital camera — from Clark’s old company, Silicon Graphics — would take a photo of the fish tank and a link to it would appear on the web page, in three different image formats: RGB, GIF or JPEG (the latter an emerging standard for compressed image files).

It was, of course, a gimmick to highlight the multimedia capabilities of Netscape Navigator. But it got the message across: this was a web browser that went beyond text-based internet services, like bulletin boards. This was a new world; a world of images, audio files, and even video clips.

Rickard also mentioned the Internet Underground Music Archive website during his extensive review of the web at the end of 1994. He told his readers that IUMA was “well worth checking out,” but he sounded a note of caution: “Be aware, this is a graphics intensive site and some of the music samples are upwards of 1 meg.”

So there were still real technical bandwidth limitations to web browsing at this time, but — thanks largely to Netscape — the WWW was now a multimedia experience. With a new year about to dawn, one thing was for sure: it was time for the ROMbloids to move aside, because 1995 would be the year of the Webuloids.

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.