Multimedia Gulch in 1994: The Age of Interactive CD-ROMs

Multimedia Gulch was a trendy neighbourhood in San Francisco in the 1990s, home to wannabe rock stars making CD-ROM adventure games. They lived fast in a time of slow modems.

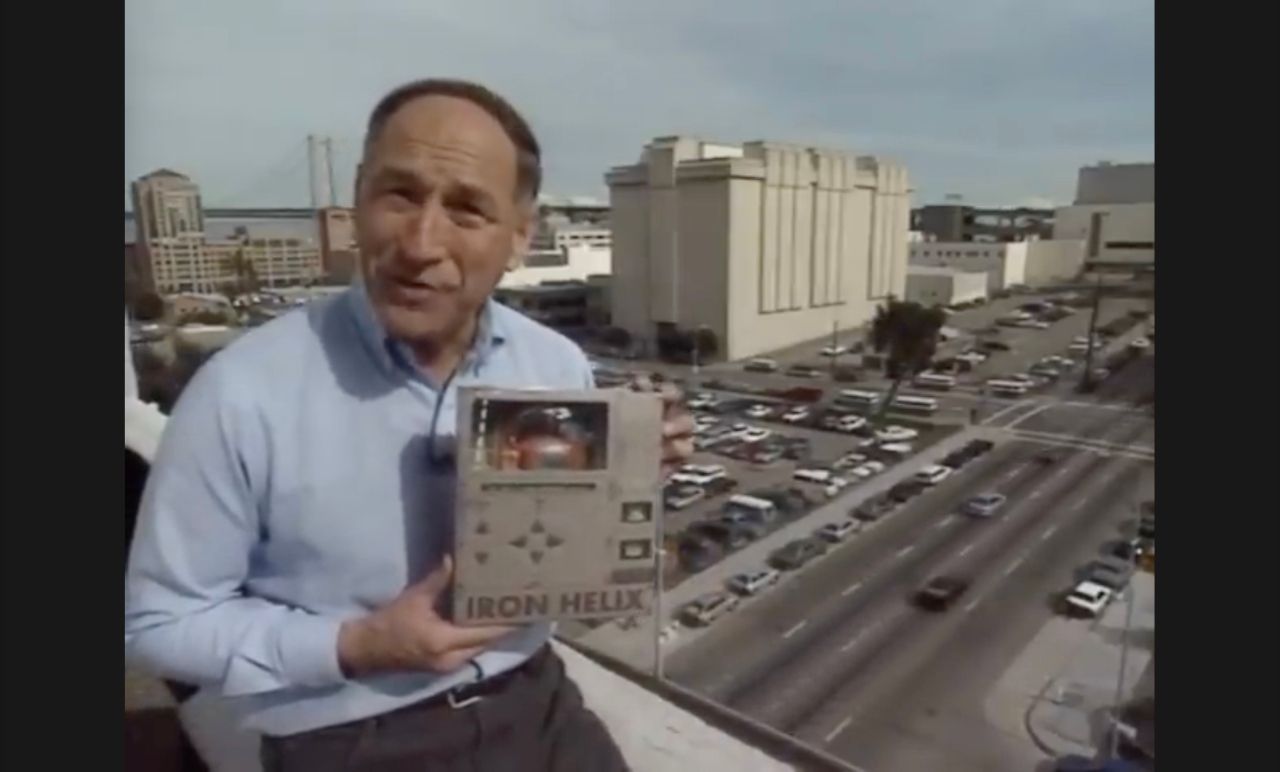

In April 1994, the PBS tv series Computer Chronicles devoted an entire show to multimedia.

“The personal computer revolution started about 40 miles south of here in an area now called the Silicon Valley,” said the show’s host Stewart Cheifet, as he sat atop a building overlooking San Francisco Bay. “But there is a new technology revolution underway and it's called multimedia — redefining the way we create and consume information and entertainment. The center of this new revolution is right here in San Francisco in this part of town now called Multimedia Gulch, home to dozens of new companies developing new multimedia products.”

Multimedia Gulch was in a neighbourhood south of Market Street known as the SoMa district. During the Web 2.0 boom of the 2000s, it would become the home of exciting new startups like Twitter and Foursquare. Web companies continue to base themselves in SoMa to this day — in October 2023 I interviewed the CEO of the web development company Netlify, which had just moved into an office around the corner from South Park.

But back in 1994, before the internet took hold, SoMa was populated by multimedia startups creating CD-ROMs, as well as early digital media luminaries like Wired magazine and Macromedia (which Fortune magazine described as “a leading maker of software used for creating CD-ROMs” in a March 1994 article).

CD-ROMs

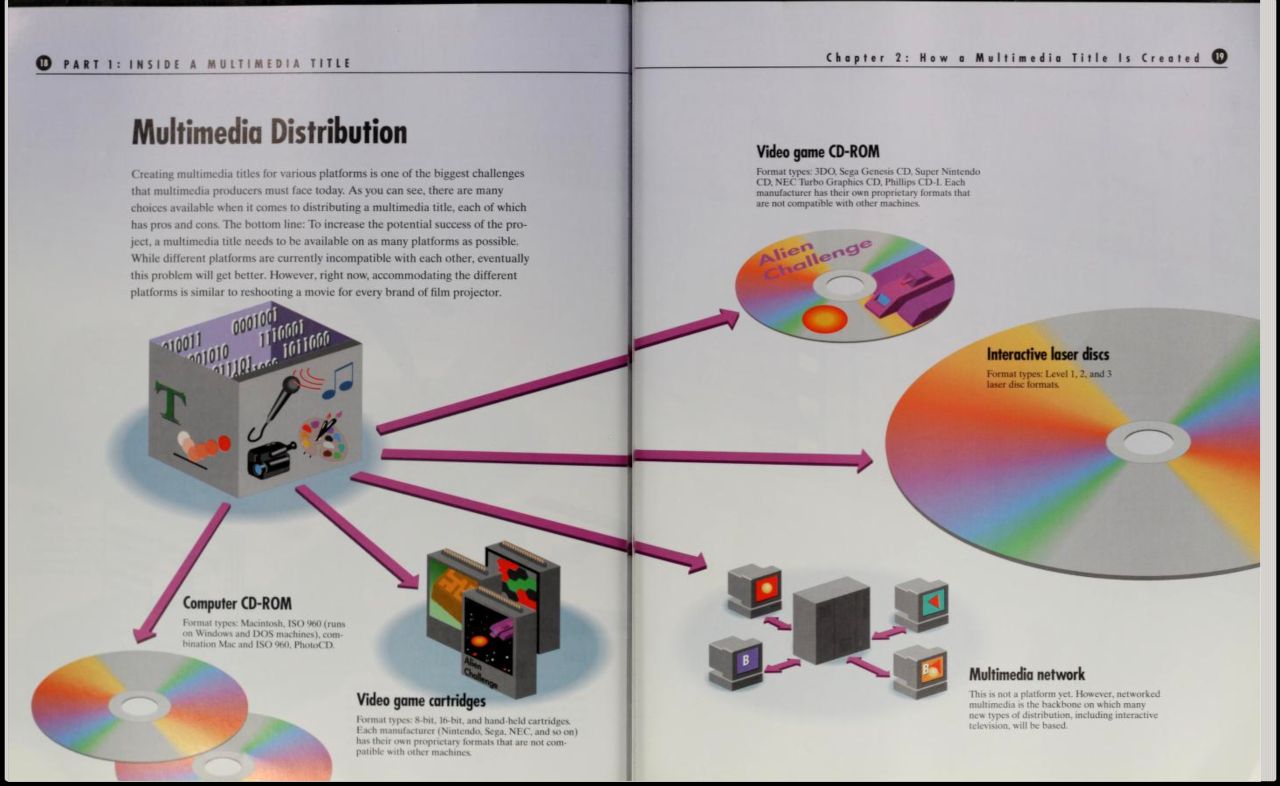

Since this was before the World Wide Web had gained traction, the default format for multimedia at this time was CD-ROMs — an acronym for “compact disk read-only memory.” CD-ROMs were identical in appearance to audio CDs, only they contained data for a computer instead of audio for a CD Player.

I’m writing this in an era where streaming media from the almighty cloud is not only common, but ubiquitous. Disks of all kinds are now rapidly going obsolete. So it can be hard to comprehend that people used to have to insert an object into a machine, in order to consume media. Indeed, back in 1994, free CD-ROMs delivered by AOL were how most US residents connected to the internet.

“Each disk can hold up to 660 megabytes of information — the equivalent of 471 floppy disks,” reported CS Monitor at the start of 1994. This was more than enough memory to hold a series of videos, animations, sounds and images, although not enough for a full-length movie.

The prevailing attitude in Multimedia Gulch in 1994 was that CD-ROMs were analogous to audio CDs, which had overtaken vinyl and cassettes by the end of the 1980s. I'd bought my first CD, R.E.M.’s Green, at the end of 1988, shortly after I turned seventeen. My cassette tape collection, including Prince’s Purple Rain, Duran Duran’s Seven and the Ragged Tiger and George Michael’s Faith, was soon consigned to history.

From an entertainment industry perspective, it was hoped that CD-ROMs would do for multimedia what CDs did for music and VHS tapes did for movies. That is, entice tens of millions of consumers to purchase them. Certainly, the technology for running CD-ROMs was becoming cheaper and more widely available. CD-ROM players were fast reducing in price (you could buy one for “as low as $199,” said CS Monitor) and, even better, more and more computers were being sold that had in-built CD-ROM drives. So there was a good chance that if you had a PC in 1994, it either had an in-built CD-ROM player or you had shelled out an extra couple of hundred bucks for one.

So multimedia producers weren’t crazy to think that CD-ROMs might emulate the success of audio CDs. But they wanted to take the comparison a step further. The creators of multimedia wanted to live a rock and roll lifestyle too, just like the creators of CDs.

The CD-ROM Scene in 1994

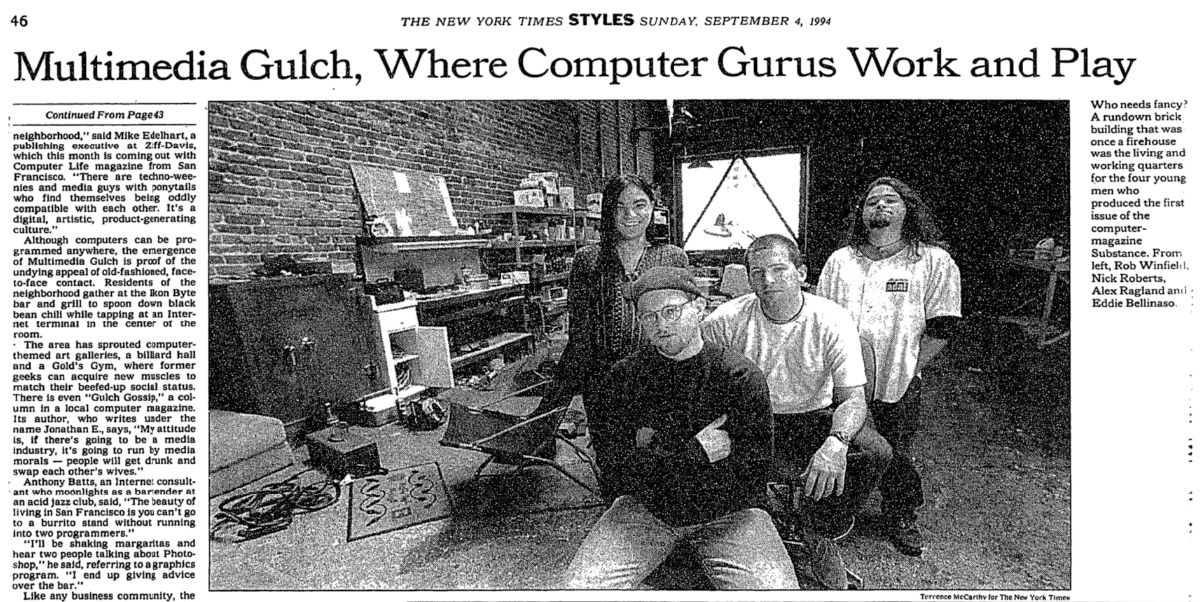

In its “Styles” section in early September 1994, the New York Times tried to convey Multimedia Gulch as a hip scene in San Francisco. But instead of making CD-ROM creators sound cool, the article ended up portraying them as clichéd and slightly ridiculous.

“There's a lot of similarities to being in a band, trying to put out your first record, and doing this,” the Times quoted a pony-tailed man named Joe Sparks, described as “a 29-year-old programmer who works in his home in a tiny nook with drawn blinds, surrounded by synthesizers, a guitar, computers and a low-tech stereo.” He once played in a punk rock band, the article added (of course he did).

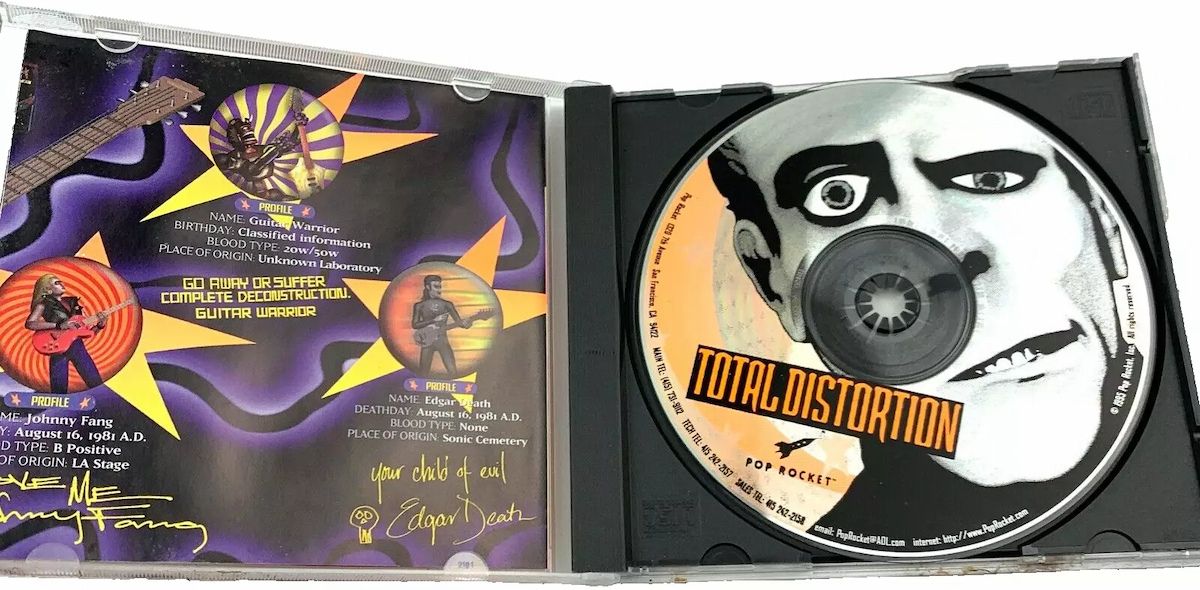

At the time, Sparks and his wife Maura were creating a CD-ROM entitled Total Distortion, an improbable sounding adventure game “that requires the user to make a music video and sell it to a big-time producer who is prone to refuse the user's phone calls.” Sparks had been working on the game since 1992, but it took another year after the NYT profile for it to be finally released — earning it a somewhat unkind entry into GameSpot’s “vapourware hall of shame.”

The denizens of Multimedia Gulch were trying hard to make CD-ROMs into a popular media format, like CDs or VHS tapes. The problem was, titles like Total Distortion and Substance (a digital magazine about music, also featured in the NYT article) weren’t very convincing as consumer products. Much more successful was the new multiplayer video game Doom, which Netscape co-founder Marc Andreessen was known to play throughout 1994. But even Doom was years away from developing into a fully interactive product.

Slow Modems

Part of the appeal of CD-ROMs in 1994 was that they enabled a form of interactivity that simply wasn’t possible on the Web at the time — due mainly to the limited speeds of dial-up internet.

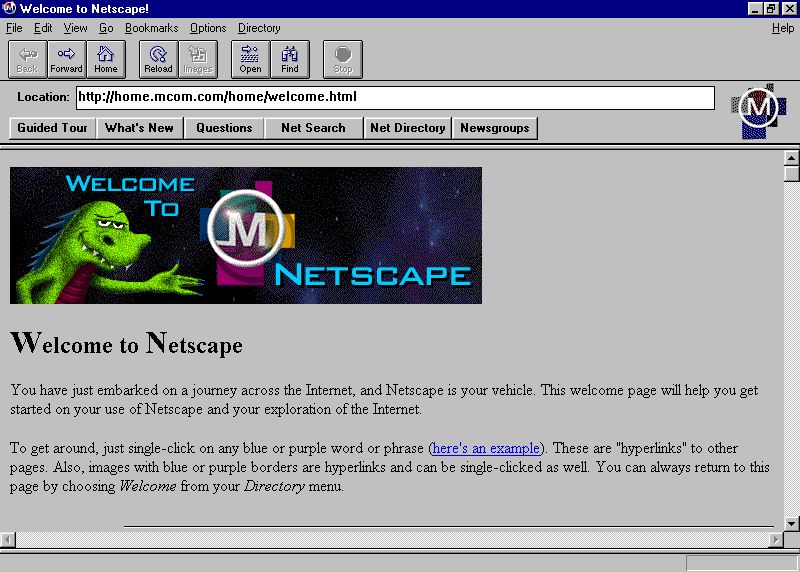

By October 1994, the newly formed startup Netscape was ready to release a “0.9 Beta” version of its web browser, then called Mosaic Netscape (it would soon be re-named Netscape Navigator). “Mosaic Netscape is a built-from-scratch Internet navigator featuring performance optimized for 14.4 modems, native JPEG support, and more,” Marc Andreessen announced on the WWW-Talk mailing list.

The "14.4" part meant kilobits per second. Translated to modern terminology, that’s 51.84 megabytes per hour — incredibly low from today’s perspective. Nowadays, many people routinely get 100 megabytes per second (sometimes much more) on a broadband fibre connection. But thirty years ago, it was the dial-up era of internet connections — and that meant using your telephone line to connect.

A modem, short for "modulator-demodulator,” was a piece of equipment that translated (or modulated) the zeros and ones of digital data from the internet into phone-line signals, and then back into zeros and ones for your personal computer. So when we’re talking about multimedia in 1994, bear in mind that browsing the web was painfully slow. Even supporting the downloading of images was a big deal.

In a November 1994 review of the Netscape beta, David Brody wrote that “Mosaic Netscape was developed with the aim of addressing the needs of bandwidth deprived computer owners like me,” but that it was still “a snail when it comes to loading those cool color pictures and happening sounds.” He noted that Mosaic Netscape had a nifty feature to help cope with slow downloads: it would allow the user to go on browsing while the browser downloaded items in the background. This would become a familiar feature of the early web browsing experience in the mid-1990s — images loading “a piece at a time” (as Brody put it), so that you could at least read the surrounding text while you waited for the full web page to appear.

So while the multimedia Web did in a sense arrive with the beta of Mosaic Netscape, the user experience was far from optimal. Which is why CD-ROMs were still seen as the best format for multimedia in those early years of the Web.

Multimedia and Interactivity

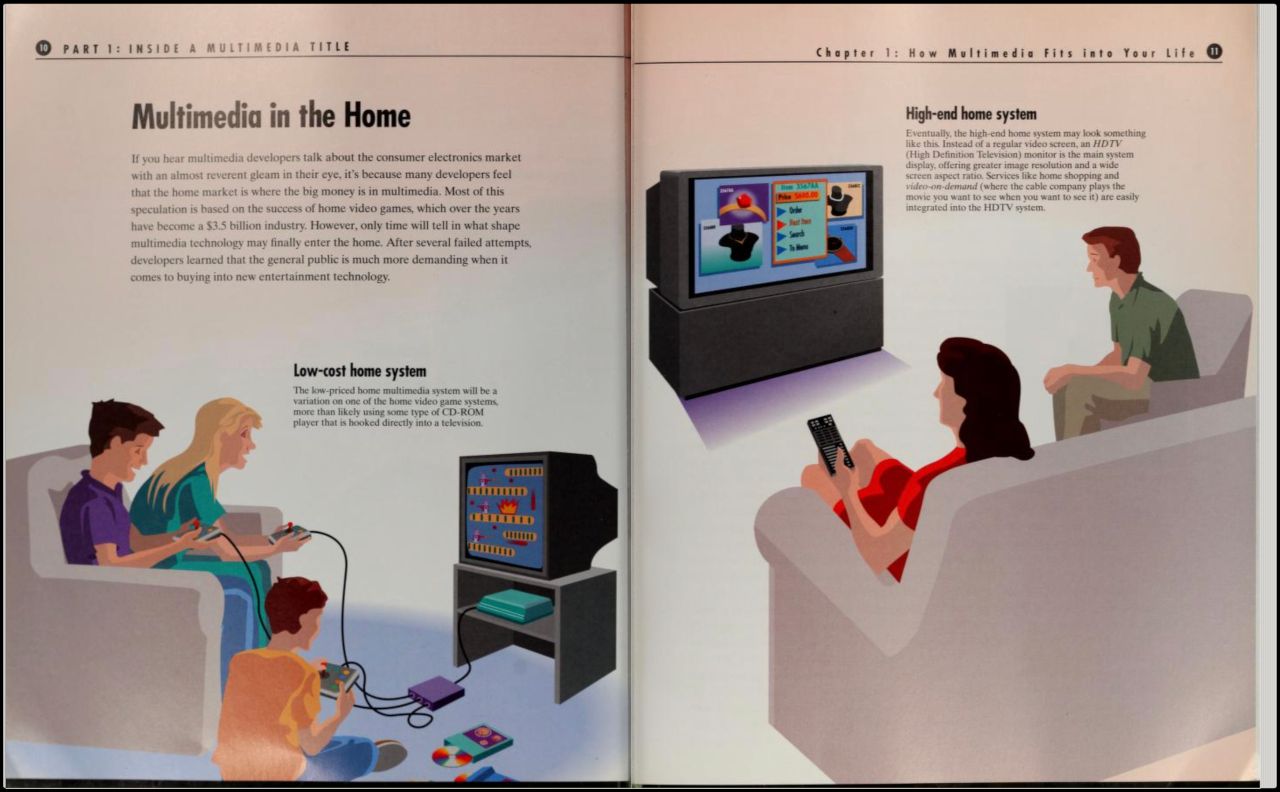

In a 1994 book entitled “How Multimedia Works,” Erik Holsinger defined interactivity as the key ingredient that separated multimedia from other forms of media, such as television. After noting that a TV news program isn’t interactive, he wrote that a “multimedia title” could make it so.

“A multimedia version of a newscast could contain all the elements of the newscast, but you’d be the one who tells the newscaster what information you want to hear and when you want to hear it. The choice is yours. Just click a button, touch a screen, or press down on a keyboard, and you can call the shots within a multimedia title.”

In theory this sounded great, but in the book Holsinger struggled to define the form factor that multimedia would inhabit. Everyone had a square TV box in their lounge in 1994 and many of us had CD players in our bedrooms, but what exactly was a “multimedia machine”? Like many in the industry, Holsinger thought multimedia in the home would start out as “some type of CD-ROM player that is hooked directly into a television,” and over time become integrated into cable TV.

Even though nobody had yet figured out how people would consume multimedia, there was no shortage of computer software for people to create it. With software like Apple QuickTime, Adobe Photoshop and Macromedia Director, it was possible for computer-savvy people to create multimedia content on their personal computers. It wasn’t cheap to buy this software and there was a technical learning curve, but the tools were available. These same companies — Apple, Adobe and Macromedia — would go on to provide some of the key web building tools of the mid-to-late 1990s.

What Happened to the Gulch?

Of course, the Web eventually usurped CD-ROMs as the default way to consume multimedia, but the name “Multimedia Gulch” took longer to go away. As late as October 1999, the San Francisco Chronicle published a feature article about the continued growth of the SoMa area for “digital media companies.”

“There are now more than 35,000 people working in the multimedia industry in The City, according to a new survey from the UC-Berkeley Haas School of Business,” reported the Chronicle. “The vast majority of them work in Multimedia Gulch.”

As for Joe Sparks, one of the “gurus of Multimedia Gulch” profiled by the New York Times in 1994, his CD-ROM company folded in the mid-90s after the market failure of Total Distortion. Soon after, he joined Macromedia and pursued a career in online video.

In the next dot-com era post on Cybercultural, we review CD-ROM titles from actual rock stars in 1994. They were delightfully bad!

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.