Paradise Lost: How Moreover Won & Lost the Real-Time Web

News aggregator Moreover was born in the late 1990s, at the same time as Google, and at one point dominated the real-time news market. So why did Moreover turn its back on the consumer web?

The late 1990s was the middle of the Dot Com boom. Looking back, we tend to associate this period of intense growth with e-commerce startups. During 1998, eBay went public, Paypal was founded, Amazon.com was spending big to “expand its reach” and Pets.com launched. Also started in the late 90s, but with much less noise, were two pioneering information management businesses. In 1998, two Stanford University students working from a Menlo Park garage were testing a new search engine, called Google. At about the same time, three Englishmen joined forces to create a “news aggregator” called Moreover.

We all know the Google story by now. Much less well known is the story of Moreover and how it changed the way we consume news. Basically, what Moreover did was gather news headlines from all over the Web and make them available to other websites to use. Both were pioneering search engines, in their own way. Google ‘spidered’ the Web for links, while Moreover ‘scraped’ news websites for headlines. Google ended up building the best all-purpose search engine in the world. Moreover succeeded in building not only the best online news distribution tool, but (almost by accident) the first news search engine. Indeed Moreover was the catalyst for Google building its own news aggregator, Google News.

The story of Moreover is also one of opportunity lost, for both Moreover’s founders and for consumers of online news. Because within the space of just a few years, Moreover switched from a consumer business model to an enterprise model. It went from being an ‘information wants to be free’ enabler, to the lock and key of information gatekeeper.

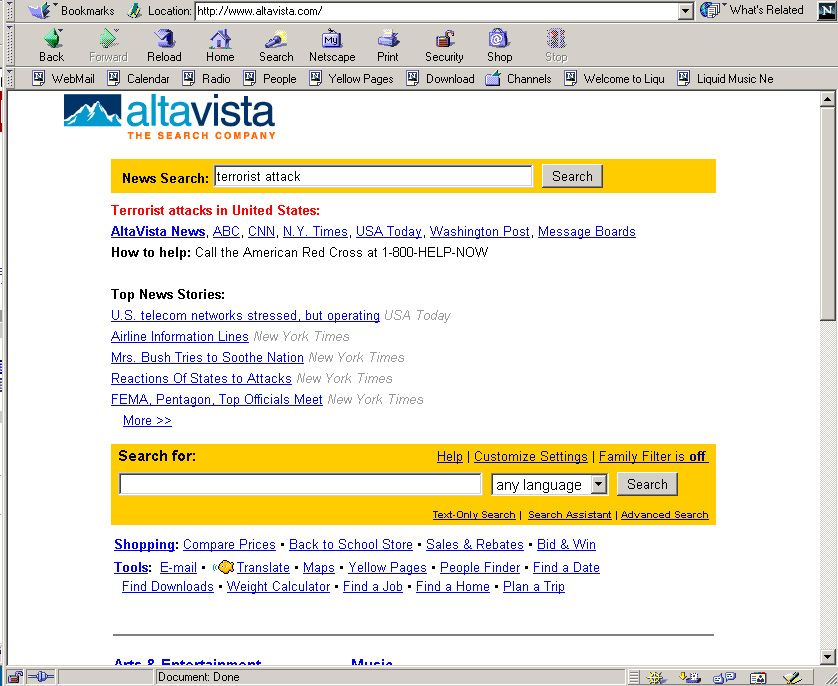

It’s not as if Moreover wasn’t successful in the consumer market. In 2001, Moreover had Google on the ropes as a distributer of online news to consumers. When the 9/11 tragedy struck, the best way to get updates online was the Moreover-powered news search on AltaVista. But soon after, Moreover turned its back on the consumer market for the easy money in enterprises.

It’s particularly galling as a consumer of online news today, since the powerhouses of this era — Facebook and Twitter — are terrible at filtering and organizing online news. Precisely the expertise that Moreover had, and still has.

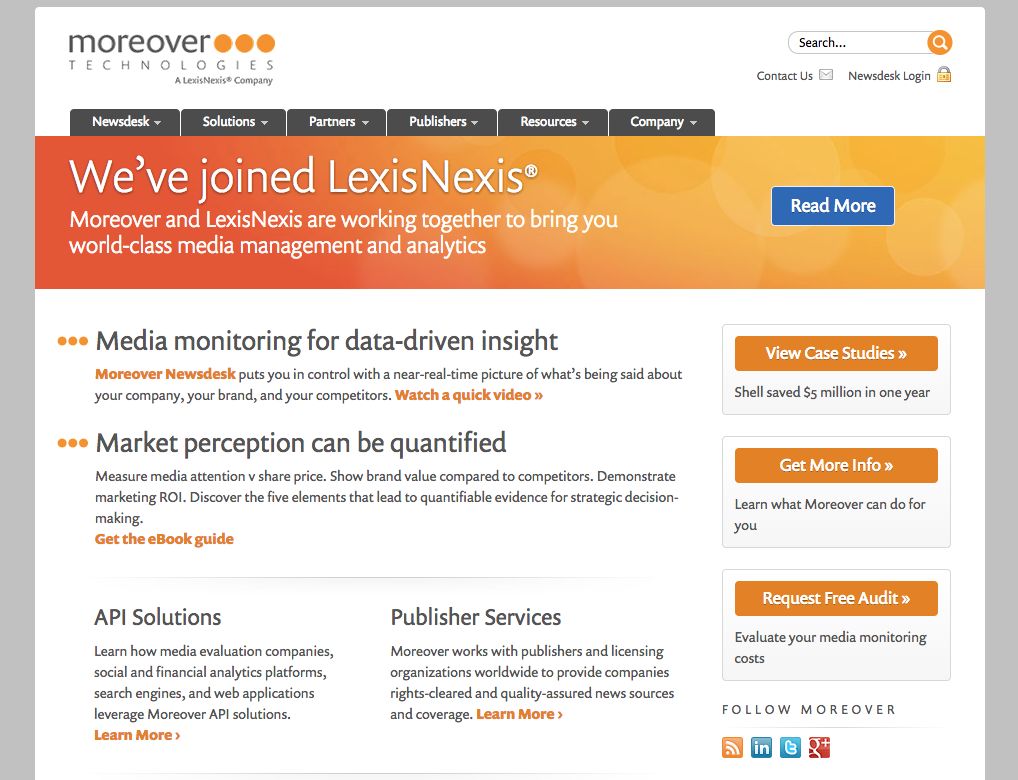

Late last year, Moreover was quietly sold for the third time. This latest acquirer seems appropriate to the fate that Moreover chose for itself. The sale was to LexisNexis, one of the earliest gatekeepers of electronic information (it was founded in 1970).

Moreover is a good case study of what happens when consumer innovation is stifled early on. Had Moreover kept going on its original groundbreaking path, it may well have solved some of the problems that frustrate us today on the consumer Web: a lack of intelligence in sourcing quality news, the paucity of quality topic tracking tools, a general lack of interest amongst the big companies (Google, Facebook and Twitter: I’m looking at you!) to let users filter and organize information. Moreover’s technology could’ve made a difference, had it chosen a different route.

How Moreover Got Started

The founders of Moreover were Nick Denton, David Galbraith and Angus Bankes. Galbraith and Bankes were the developers, Denton the business guy. Denton is the most well-known of the trio now, as the always quotable founder of blog network Gawker. In 1998, he left his job as a journalist at the Financial Times in order to raise money for Moreover. He roped in two early investors, angel investor Richard Tahta (a senior director at Amazon.co.uk) and British venture capitalist Christopher Spray of Atlas Venture. A press release dated June 2, 1999 announced the seed round, which valued Moreover at $3.75 million.

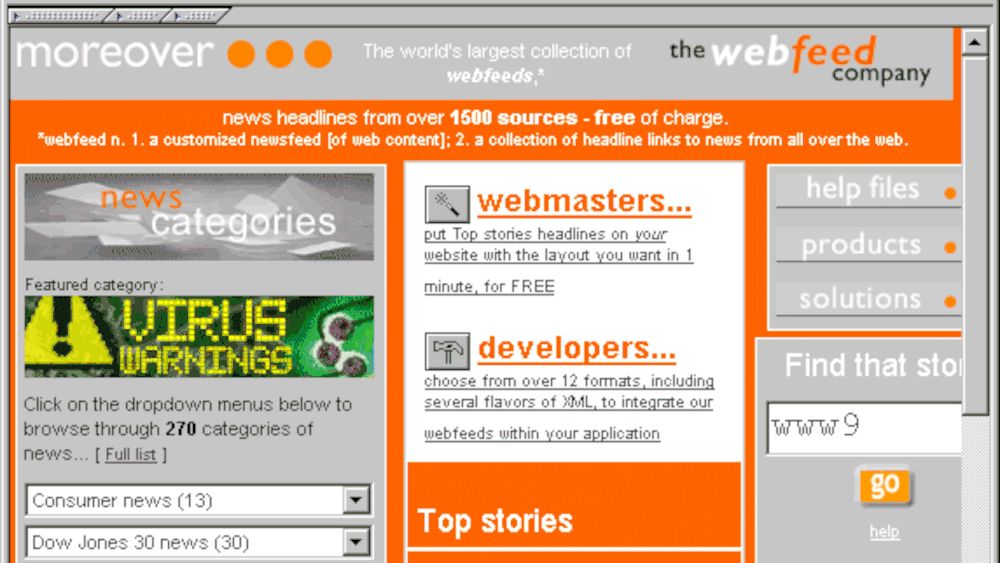

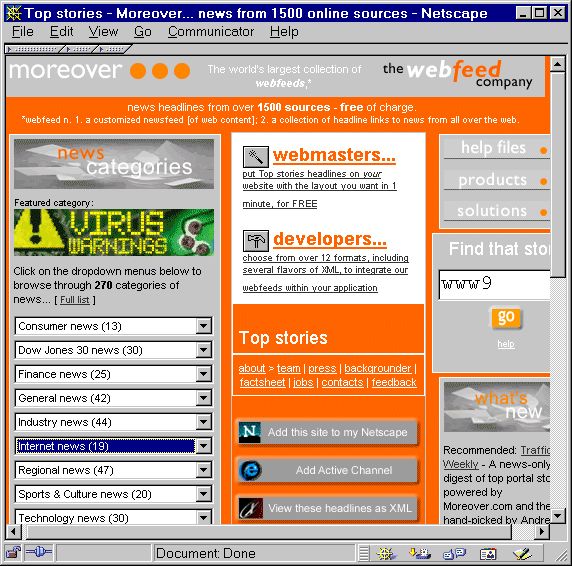

On the same day, Moreover launched its website. It enabled anyone to add a list of news headlines to their own website, by copying and pasting a snippet of code. Denton’s ambition was “that every site should have a Moreover section, of web-style newsfeeds that we provide.”

The service was free for webmasters and developers. But to make money, Moreover also had a premium offering for corporate and media websites. Search engine portals were its prime target. Portals were all the rage in the late 1990s and early 2000s, as destination webpages for all kinds of content: news, email, weather, and more. Moreover’s news headlines would be perfect for portals, as well as company intranets (which were essentially portals too — I know this because I built and managed intranets for a living back then).

Although it charged companies to access its news feeds, Moreover itself didn’t pay news providers for the links. Instead it used a clever technology hack to “scrape” the headlines. At the end of August 1999, Denton described Moreover to a technical message board as “an internet service which scrapes headline links from about 1,500 sources on the web, and across more than 150 categories of news.”

This ‘scraping’ method eventually attracted controversy, because to some news media companies ‘scraping’ was a synonym for ‘stealing’. The way Moreover preferred to view it was that it was doing the world a service, because it organized information — much like Google was doing. As David Galbraith described it for a presentation at the 2000 World Wide Web Consortium, held during May in Amsterdam, Moreover was “taking unstructured data and delivering structured results in various flavors of XML.”

The Rise of RSS, Blogging & The Real-Time Web

In 2000, a Web publishing format called RSS began to gain momentum. Originally developed by Netscape in 1999, RSS was based on XML and enabled websites to publish a real-time feed of news. The acronym had several definitions: Rich Site Summary, RDF Site Summary, or Really Simple Syndication. The reason for this was that development on RSS had forked into two separate projects: the first run by blogger and Web developer Dave Winer, the other a breakaway group of entrepreneurs and developers called the RSS-DEV Working Group.

In February 2000 Denton and Galbraith traveled to Silicon Valley to get their heads around the politics of RSS. The pair ate spicy noodles in Menlo Park with Dave Winer. [Incidentally, I too have had the privilege of eating spicy noodles with Dave Winer — along with Michael Arrington, Gabe Rivera and Fred Oliviera — in October 2005.] Despite the appeal of Winer’s format, which was already popular with bloggers, Moreover sided with the RSS-DEV Working Group — which didn’t release its version until December 2000.

Moreover soon cornered the market on the commercial use of RSS. It began to position itself as “the webfeed company” and claimed to have “the world’s largest collection of webfeeds.”

Moreover also tried to grab a big slice of the blogging market. Sometime during 2001, Nick Denton tried to pursuade the Moreover board to buy pioneering blog publishing platform, Blogger. The price was $3m, but the board balked at the deal. Frustrated at not getting his way, Denton quit as CEO in August 2001.

As an ex-journalist, Denton saw potential in blogging and he began to experiment with this new form of publishing. He bought the domain name Gizmodo.com in July 2002, which became the early flagship of his media empire Gawker.

Despite Denton eventually being proven right about blogging, Moreover was right to keep its focus on news aggregation in 2001. Indeed, shortly after Denton resigned as CEO, Moreover made a breakthrough as a source of real-time news. It was due to the 9/11 tragedy. That fateful day, everyone wanted news updates urgently. It turned out that AltaVista, not Google, was the fastest way for people to get updates. That was thanks to the Moreover-powered ‘Top News Stories’ widget on AltaVista, which meant the latest news stories about the terrorist attack were just a click away. AltaVista also had a special ‘News Search’ box on its homepage, which enabled users to search across the more than 2,000 news sources scraped by Moreover at that time.

As well as AltaVista, Moreover had licensed its technology to other leading search engine portals of the era — including Yahoo!, MSN and AskJeeves.

Ironically, Google had overtaken AltaVista as the leading search engine on the Web earlier in 2001. But Google hadn’t realized the importance of real-time news updates and search, until it saw Moreover’s widget on AltaVista. Development on Google News began shortly after, finally debuting in September 2002. Several months after that, Google acquired what Denton had coveted — it bought Blogger for an undisclosed sum in February 2003.

Google may’ve been slow off the mark with real-time news, but after 9/11 it made all the right moves. The same can’t be said for Moreover after 2001.

The Switch to Enterprise

Moreover’s exposure on the leading dot-com search engines was as far as it would go in the consumer world. Soon after, it began chasing the easy money in the enterprise world.

By the middle of 2002, Moreover was promoting itself as “a provider of real-time information management solutions to Global 2000 companies.” Its PR became a jumble of enterprise IT buzzwords. Moreover promised to “impact business decisions,” “capture the most actionable information” and “provide business users with continuous function-specific information.”

This switch in focus was a great shame. It’s tempting to wonder how far Moreover could’ve gone in the consumer Web market, considering that another golden era (which came to be termed ‘Web 2.0′) was just around the corner. Consider that Moreover had built a pioneering news syndication and distribution service. It had virtually cornered the consumer market for this, with its near blanket coverage on the major search engines of the era. The only major search engine Moreover wasn’t featured on was Google. But at the time, 2000–2001, Google was a distant second to Moreover on real-time news. Google wasn’t yet a big threat.

Yet despite holding all the cards in the nascent RSS and news syndication market, Moreover went the conservative route and marketed itself to corporations. The conclusion is clear: Moreover missed a huge opportunity to out-maneuver Google and dominate the real-time Web.

Blogger Jason Kottke, who worked as a designer for Moreover from late 2000 to mid 2001, lamented in an October 2003 blog post that Moreover was no longer “at the forefront of this still-developing space, building on those innovative ideas that they weren’t able to execute on.” The frustrating thing is that Moreover was certainly capable of executing on its innovations. It simply chose the safer route. Co-founder David Galbraith later suggested this was due to internal pressure from its board to find “a revenue model.”

The Exit: Verisign

Despite the opportunity lost in Web 2.0, Moreover’s enterprise pivot was undoubtedly profitable. It also led to Verisign’s $29.7m acquisition of the company in 2005.

Verisign, an Internet infrastructure company, wanted to become the Grand Central Station of real-time news — the central point from where it all flowed. A not unrealistic goal, considering that at the time Moreover was gathering news from “more than 12,000 news sources and millions of blogs.” Google was worried about this, so it put in a late bid for Moreover. But the deal went ahead with Verisign.

Verisign made another, similar, acquisition at the same time, buying weblogs.com from Dave Winer for $2.3m. Weblogs.com tracked any change made to a weblog, via a simple “ping” to the web server. As blogger Tom Foremski put it, the two acquisitions together enabled Verisign to “track most new content published online, and track who accessed it and where.”

At a time when RSS and blogs were the primary ways to disseminate news on the Internet, Verisign was suddenly looking like a potential kingmaker.

Verisign had at least a couple of years with which to press its advantage, but it frittered it away with corporate dithering. It wasn’t until 2007 that social networks — and in particular Facebook and Twitter — began to challenge RSS and blogs as content distribution platforms. But from 2005–2007, Verisign did virtually nothing with Moreover on the consumer Web.

What Verisign did instead was double down on the enterprise strategy. Which meant more impenetrable marketing-speak. In May 2006, Verisign announced the release of something called the “Moreover Connected Intelligence (CI) Newsdesk 3.0.” The market yawned.

At about the same time, I was writing on ReadWriteWeb about how a young startup called YouTube had doubled its traffic in May 2006, from 6.6m unique visitors in April to 12.6m in May (YouTube now has over a billion users). Of course in 2006 nobody had any clue how big social networking would become, but something was happening here. Whatever it was, Google noticed. It acquired YouTube in October 2006 for $1.65 billion, at the time a staggering amount.

In this context, Moreover’s connected-newsdesk-blahdy-blah was at most dull and at worst irrelevant.

Moreover continued to sleepwalk through 2007. By the end of that year, Verisign had given up completely — it announced a plan to sell off Moreover and other “non-core” businesses.

To add to the frustration, Moreover’s scraping of news feeds finally got it into legal trouble. In October 2007, Associated Press sued Verisign for copyright infringement. The lawsuit was settled “amicably” in August 2008. Although the terms weren’t disclosed, the fact that Moreover continued to include AP’s links in its service suggests that a licencing agreement was reached.

The Rise of Social Media; Moreover Goes Indie Again

After yet more dithering, Verisign finally sold Moreover in May 2009 to a group of investors led by former AOL executive Paul Farrell. Included with the transaction was weblogs.com, which led to a name change for the combined company: Moreover Technologies, Inc. At the time of the sale, Moreover claimed to catalog “450,000 news articles daily from more than 30,000 news sources.”

Paul Farrell assumed the reigns as CEO of the newly independent Moreover just as social media was starting to dominate the online news landscape. The month after Moreover was sold, Facebook began to make public posting the default for its users. Prior to 2009, Facebook was primarily a private social network. This shift in strategy by Facebook was largely in response to the growing popularity of Twitter, which had a breakout year in 2009. In a June 2009 blog post, Moreover itself noted that “the traditional blog [is] no longer the main vehicle for expression.” Instead, it was “micromedia platforms like FriendFeed, Posterous, and Twitter.”

While the term “micromedia” quickly went out of fashion, the big picture trend was evident by the end of 2009: social media was taking over from RSS and blogging as the main distribution method for online news.

Under Farrell’s leadership, Moreover adapted to this seachange. It continued to focus on the enterprise market, so nothing earth-shattering was developed. But to its credit, Moreover poured resources into social media monitoring. In June 2010, it announced a new product called the ‘Social Media Metabase business intelligence portal’. Moreover was now scanning 12 million news sources, a 390% increase from a year ago — thanks to the addition of millions of new social media accounts.

Gatekeeper 2.0

Nothing of note happened for the next four years, until Moreover was acquired by LexisNexis in October 2014 for an undisclosed sum. The acquisition wasn’t even noticed by the technology media. Since LexisNexis is a legacy gatekeeper of digital information (primarily legal content), it just seemed like a big fish swallowing a smaller one.

But the LexisNexis acquisition was deeply ironic, because Moreover was created in 1998 to be the antithesis of LexisNexis.

‘Information wants to be free’ was the rallying cry behind early Web innovations like Wikipedia and Blogger. In part, that philosophy was in response to the first wave of digital information management companies — like LexisNexis. Those companies held information under lock and key. If you wanted access, you had to pay for it.

During its first few years, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Moreover had challenged this model. It had made access to information — in this case, news content — much more freely available. It put that content onto many of the major search engines and portals of the Dot Com era. It allowed bloggers and small niche websites to access and use that content too.

In my research I stumbled across an article dated 1 January 2000, in which two LexisNexis executives discuss the then young startup Moreover. “Wasn’t this UK company,” asked the reporter, “by providing news feeds for free, flying in the face of the established online vendors?” The European Director of LexisNexis at the time, Jon Webb, agreed that Moreover presented a challenge. But he questioned its long-term viability. “If all the information which is currently for free remains free and increases,” said Webb at the beginning of 2000, “then where is the profit going to come from to pay for the endeavour? The quality must suffer and where is the incentive for you, as a journalist, to write, or me manage? There are still many people out there who value trusted sources.”

It turns out that Jon Webb of LexisNexis was right: there wasn’t enough profit for Moreover in providing news feeds for free. Or at least, not enough profit to satisfy Moreover’s board and investors. The bursting of the Dot Com bubble didn’t help. So in 2001, at the same time it was successfully beating Google on real-time news, Moreover began to look for a solid revenue stream. There was an easy solution: sell its news aggregation technology to enterprise customers.

In short, in 2001 Moreover became an information gatekeeper — just like LexisNexis.

The further irony is that Moreover was able to become a gatekeeper despite not paying for information itself. The only exception was when Moreover was sued — then it had little choice but to pay. For the most part though, Moreover freely ‘scraped’ information from thousands of news sources around the Web.

What If…

What if Moreover had continued to make its technology available to consumers for free, instead of becoming a gatekeeper? Instead of Verisign and then LexisNexis acquiring it, it could’ve been Google or Yahoo. Indeed, think what Twitter or Facebook would be able to do with such powerful information management software. The achilles heel of both Twitter and Facebook is that neither does a good job of filtering and organizing news content.

I’m not faulting the founders of Moreover — Denton, Galbraith and Bankes — for not following through on its early innovation. The likely cause of its switch to the enterprise market in 2001 was financial pressure. Moreover’s board wanted the company to find a revenue source fast, so it chose to focus on corporate customers.

The real damage was done in 2005, when Verisign acquired Moreover. At the time, Moreover was still well positioned to disrupt online news — after all, Google itself put in a bid to buy it. But the innovation was stifled once and for all under the bumbling management of Verisign.

That said, history also suggests that Google probably would not have done much better. Witness how Feedburner, the most innovative RSS management startup of the Web 2.0 era, was virtually shelved after Google acquired it in June 2007.

As for the information management landscape of today, it’s clear that Moreover under LexisNexis is totally irrelevant to consumers. If there’s one takeaway for the present I’d like to posit from the story of Moreover, it’s this:

We need a new Moreover for the Facebook/Twitter era.

What if a couple of clever developers like David Galbraith and Angus Bankes, and a big thinking entrepreneur like Nick Denton, took on the information gatekeepers of today? What if they developed a tool that helped us better organize social media, track the topics we’re passionate about, and discover the pearls of data we’re looking for. What a divine service that would be!

Of course, the temptation would be the same: to sell out to an enterprise company.

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.