Introduction to Bubble Blog, a Memoir of Web 2.0 (2004-2011)

The introductory chapter of my serialized memoir and internet history book, 'Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution.'

Welcome to the first post in the serialization of my Web 2.0 memoir. This is the introduction, which sets the scene for the 20 chapters to come. Each following chapter will have a number of sections, which you’ll receive as posts via email. There is also a roadmap (table of contents), which lists all the sections in order — in case you need to catch-up at any point. Thank you for joining me on this journey to the heart of Web 2.0. Please leave comments and/or share on social media if you enjoy it — this is the read/write web after all!

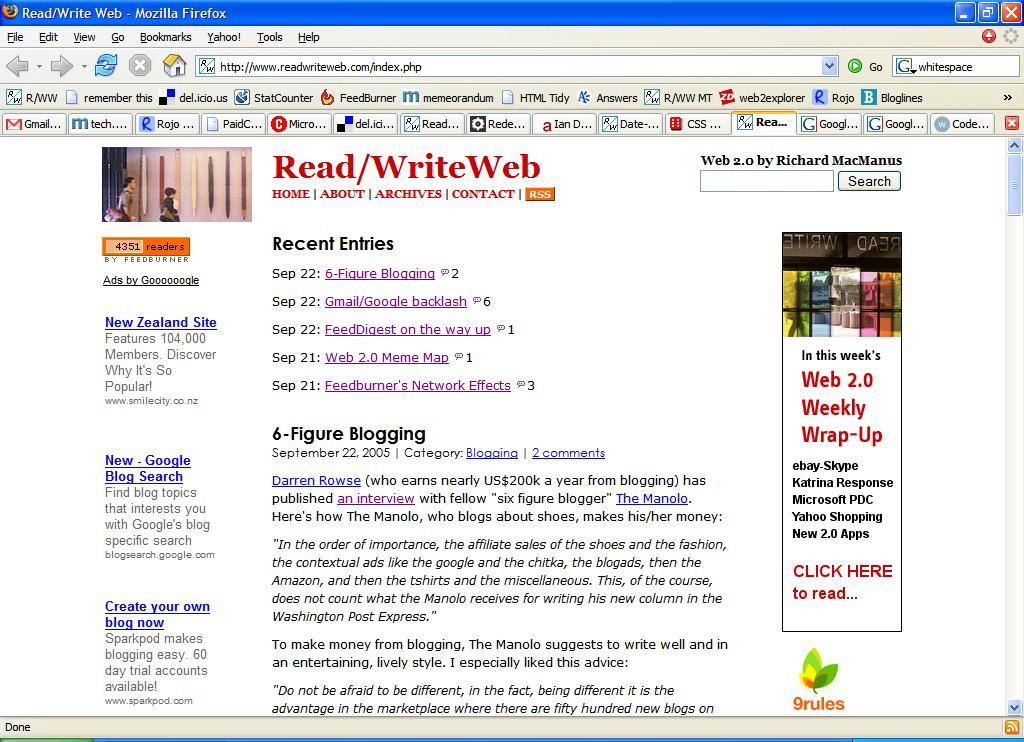

My Silicon Valley story began in September 2005, when I took my first trip to the valley — in fact it was my first trip to America. I’d just turned 34, was born and raised in New Zealand, and had barely set foot out of my home country prior to 2005. At the time, I was running a tech blog that was beginning to make some money, but only just.

A screen capture of RWW just before I visited Silicon Valley for the first time. The Feedburner RSS badge number indicates this was pre-growth spurt.

Like anyone who works in tech but has never been to Silicon Valley, I had illusions about the place before I arrived. Some were formed by the books I’d read. I had thought all startup founders were crazy, monomaniacal and heroic; like the Netscape co-founder Jim Clark, as portrayed by Michael Lewis in his book, The New New Thing. But the founders I eventually met on the ground were strivers, like me. Many had been humbled by the Dot Com boom and bust, so they were willing to listen to new ideas and new people — even ones from the other side of the world.

Some of my illusions ended up correct on the surface, but ignorant of the deeper nuances. I’d imagined Palo Alto as an idyllic, tree-lined town with a main road full of cafes and burger joints — just like on the tv show Happy Days. That one turned out to be largely true, but what I hadn’t conceived of was the long and bumpy, busy and dirty highways you must travel along to get to Palo Alto, and which separate the rich and the poor of California.

I had also imagined Silicon Valley to be populated by a mix of rich old hippies and preppy MBA types. Again, this was true in broad strokes, but I had no conception of both how friendly these people would turn out to be (much friendlier than New Zealanders, I thought, or at least much more open), and how desperately much they wanted something from me. I didn’t yet understand what it was they wanted from me; I just knew it had something to do with my blog.

To me, Silicon Valley was the modern embodiment of the American Dream, in that it was a place outsiders could arrive at and begin their striving for a better life. And the thing is, everyone is an outsider when they first arrive in Silicon Valley; or at least, that was the accepted lore when I arrived in 2005.

The author in all his geeky, naive glory in March 2005.

Even Marc Andreessen, the guy who Jim Clark piggy-backed off to launch Netscape in the 1990s, didn’t come from the valley. Andreessen went on to become the internet’s first rock star and the ultimate tech insider, but he was an outsider when he landed in the valley in 1993 (or so the story goes). He’d been raised in Iowa and went to his local University of Illinois, so I imagined his journey west was not unlike that of W. Axl Rose a decade earlier, who famously — but possibly apocryphally — stepped off a greyhound bus from Indiana and onto the hard but glamorous streets of LA.

Many years later, Andreessen would admit that he wasn’t truly an outsider. “I used to think I’d travelled sort of this weird road from rural agricultural midwest all the way to high-tech Silicon Valley, and it was an unusual thing,” he said in 2022. But then he found out that Robert Noyce, the inventor of the microchip and one of the founding fathers of Silicon Valley, was also an “Iowa farm boy.”

Some, like Andreessen — and his farm boy forbearer, Robert Noyce — would strike gold and set up camp in Silicon Valley for life. They would become the new insiders. Others, like me, would stumble upon a version of the American Dream for themselves, but ultimately go back home, to be outsiders once more.

As it happens, Andreessen is my exact contemporary (he is just over a month older than me). Like him, I completed college in 1993, in my case with a degree in English literature from my hometown university in Wellington. I don’t remember coming across the web, let alone Andreessen’s Mosaic browser, during my studies. The closest I came to the internet was using Apple’s HyperCard software for an “Information Systems” course.

Also like Andreessen, I took flight straight after college. But whereas he walked off the plane and into an engineering job in California, I arrived in Auckland, New Zealand, without a job and with dangerously low self-esteem.

A couple of years later — a personal dark ages of scrabbling for an identity, or even a reason to live — I began tinkering with web technology through website builders like Macromedia Dreamweaver and Geocities. Several years after that, in 1999 (around the time Andreessen was starting his second company, Opsware), I finally got a job in the tech industry. Well, if you can call being a technical writer and doing contract documentation work a tech career. But I had at least turned a corner and found, in the web, something to strive for.

By the time the Dot Com bubble burst in 2001, I was a Web Manager for Ericsson’s New Zealand branch. Funnily enough, I was even an outsider in that company — they didn’t know whether to put me in the IT team or the marketing team. I ended up in Marketing, but I hung out with the IT guys at coffee and lunch breaks.

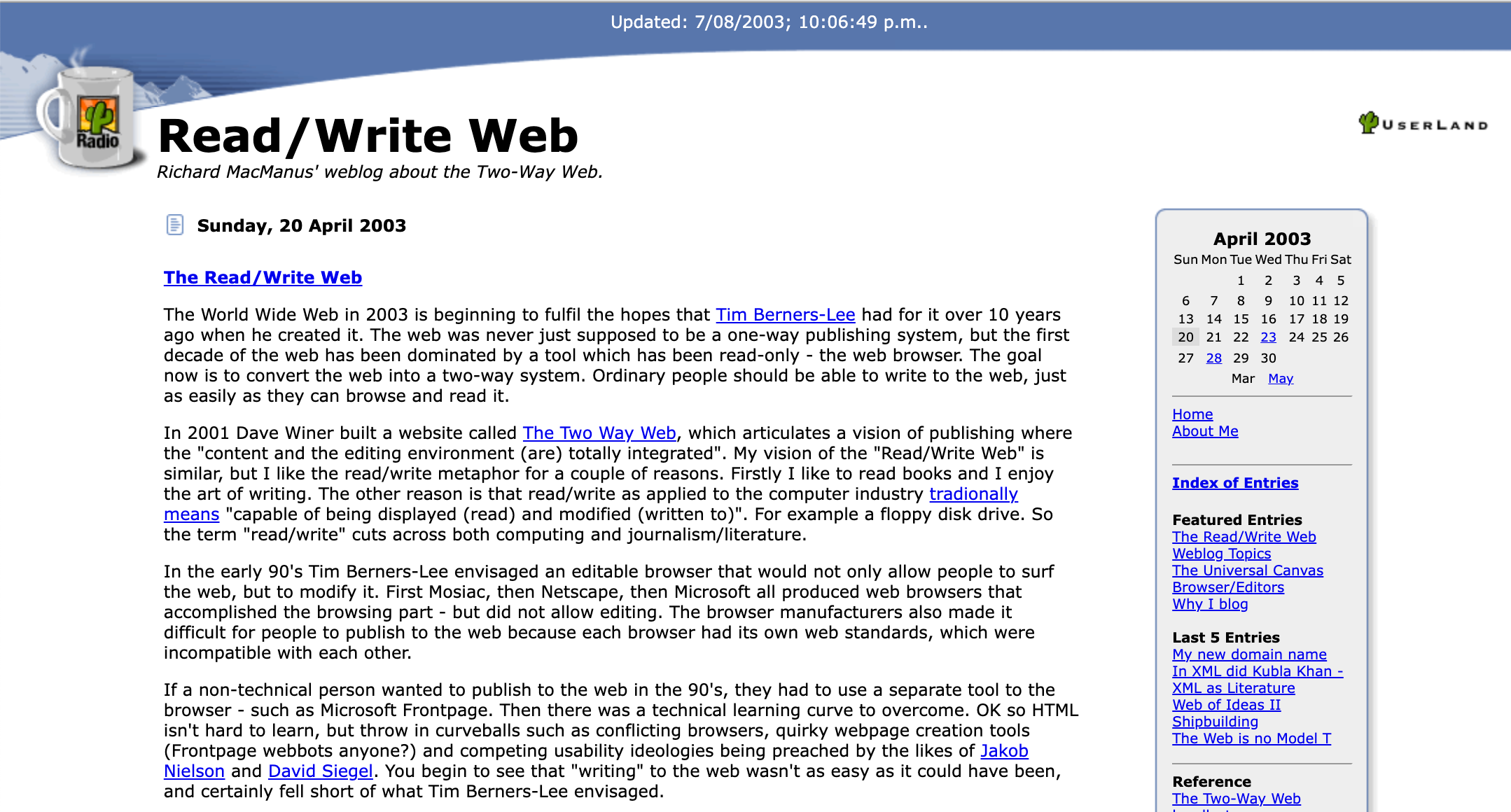

A couple of years later, in April 2003, I started a blog and called it Read/Write Web. Initially it was an outlet for me to explore the cutting edge of internet technology; things I didn’t need to know to do my job, but I wanted to know because I was curious where web technology was headed. I didn’t realize it at the time, but people in Silicon Valley were also curious about this, since it was the depths of the post-Dot Com winter.

The first RWW post, April 2003 (screenshot from Aug 03)

By 2004, winter was thawing and Silicon Valley was experimenting with the web again. Blogs were one of the emerging technologies, along with wikis and primitive social networks like Friendster and MySpace. Because I was writing about these and other web trends, people from Silicon Valley began reading my blog, commenting on it, and linking to it from their own blogs. Amazingly, these people seemed interested in what an outsider — someone who lived 7,000 miles away, spoke funny, and had not gone to Stanford or Harvard — had to say about their industry.

It’s almost impossible to believe now, but in 2005 not one of the top ten companies in the Fortune 500 was a technology company. The highest entry was Hewlett-Packard at number 11, but it had nothing to do with the web. Microsoft, which was coasting along at this point with its dominant Internet Explorer web browser, was number 41, and Intel was 50. It was a long drop then to Apple Computer at 263 and Amazon.com at 303. None of the other companies that would come to dominate our society were present on the 2005 list. Google had gone public in 2004, but it would not break the Fortune 500 until 2006. Facebook was at this time a tiny startup working out of a rented Palo Alto office.

Today’s list features three internet companies in the top 10 (at time of writing: Amazon at 2, Apple at 3, Alphabet/Google at 8) and a further two in the top 30 (Microsoft at 14 and Meta/Facebook at 27). These five companies led the way in creating the defining products of our current era — Facebook with social networking, Apple and Google with smartphones, Amazon and Microsoft with cloud computing.

This book starts in 2004; a time of transition for both insiders (like Marc Andreessen) and outsiders (like me). Andreessen was searching for his Next Big Thing, after Netscape and after Opsware. I was searching for myself, and slowly finding it through blogging. The story runs until the end of 2011, when I sold my then full-blown media company and by which point Andreessen had become the most influential tech VC in Silicon Valley.

In those intervening years, several major tech trends happened that changed our society — and our culture. Hundreds of millions more people joined the internet in the first decade of the 2000s, thanks to a worldwide broadband rollout and PCs continuing their by now inevitable Moore’s Law advances. This allowed the Social Web to happen, with companies like Facebook and Twitter becoming the centers of online conversation. Then the smartphone made it all portable, first with the iPhone in 2007 and then Android. Their respective app stores both debuted in 2008.

A geekier revolution was also taking place in Silicon Valley — and indeed the entire tech industry — over this period. The World Wide Web became a full-fledged platform for startups to build on. While web applications began as far back as 1993, with CGI scripting, it wasn’t until the 2000s that the computing environment became conducive to multimedia-driven, interactive websites — online video wasn’t really viable until 2005, when YouTube was created. Browser technology settled after Microsoft was forced by the US government to compete in 2001; and, in 2008, took a leap forward when Google released its Chrome product.

Meanwhile, companies like Google and Amazon took advantage of “the wisdom of the crowds” to create powerful web products that increasingly seemed to predict what the user wanted — be it the right search result, or the right consumer product to buy. Some websites became platforms in their own right, allowing other startups to build on top of them (Facebook and Twitter). Also, data began moving to “the cloud” after Amazon launched its first cloud computing service in 2006.

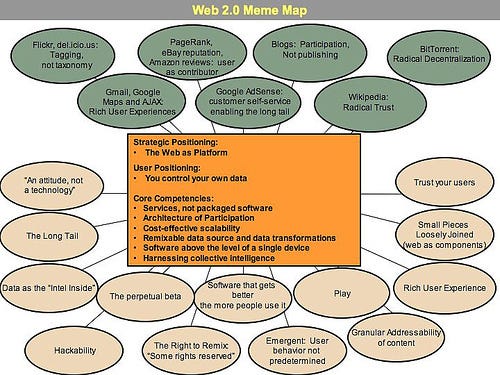

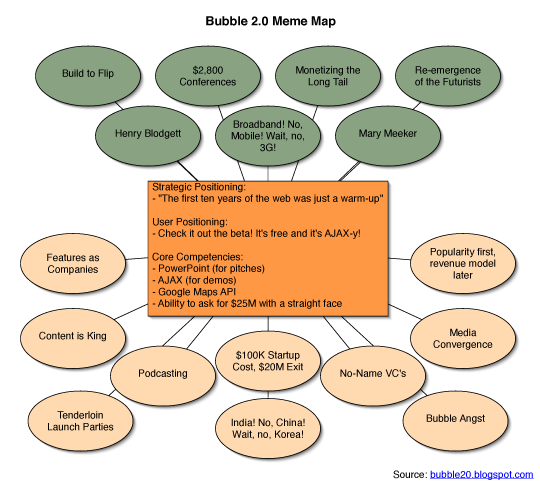

All of this, which I chronicled on my tech blog, was bundled into a term that became a rallying cry for entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley during the 2000s: “Web 2.0.” It was coined in 2004 by O’Reilly Media, a technical books company led by Tim O’Reilly, a shrewd businessman who had built his career on watching carefully what computer programmers did and then documenting it before anyone else. Web 2.0 was a clever term, because it implied that this was a second generation of the internet. It was billed as a renaissance, a re-building of the startup scene after the Dot Com boom and bust. Web 2.0 meant nothing to the outside world, but it didn’t need to — it was a term that startup founders could put in their PowerPoint presentations to angel investors (like Andreessen) and VCs, which in turn helped developers get jobs again in Silicon Valley.

Tim O’Reilly maps “the many ideas that radiate out from the Web 2.0 core.” Published 30 September 2005.

As the Web 2.0 movement grew, in 2005 and beyond, Tim O’Reilly and others attempted to retroactively define the term. But it resisted a firm definition, even after O’Reilly hired me and another blogger in August 2005 to write a book documenting it (that project was abandoned half a year later, just a few chapters in). Although O’Reilly Media went on to publish a 100-page technical report at the end of 2006 about Web 2.0 — written by a fellow tech blogger, John Musser — the meaning of the term continued to be debated for several years after that. Over time, many developers positioned themselves against Web 2.0, disliking the hype that surrounded it and claiming it was empty of technical merits.

In any case, my blog — ReadWriteWeb, a.k.a. RWW — became one of the defining Web 2.0 tech blogs. And, I must admit, I rode that hype wave for all it was worth.

A parody of the Web 2.0 Meme Map by Charlie Wood. Published 11 October 2005. Side note: the very next day, Charlie posted this quote from me: “OK so there’s a lot of hype. So the VCs are throwing money around. So get to work. Build something Web-based that mainstream people will need and want. Now’s the time to do it.” (original RWW post where that quote comes from)

I never got to meet Marc Andreessen — the ultimate insider — in person, but we did briefly communicate during my first trip to Silicon Valley.

In 2004, Andreessen had begun working on his latest startup, the weirdly named 24 Hour Laundry. This company was building a DIY social network service that would eventually be called Ning. The premise was that anyone could create their own social network, similar to how Geocities allowed anyone to create their own website in the 1990s.

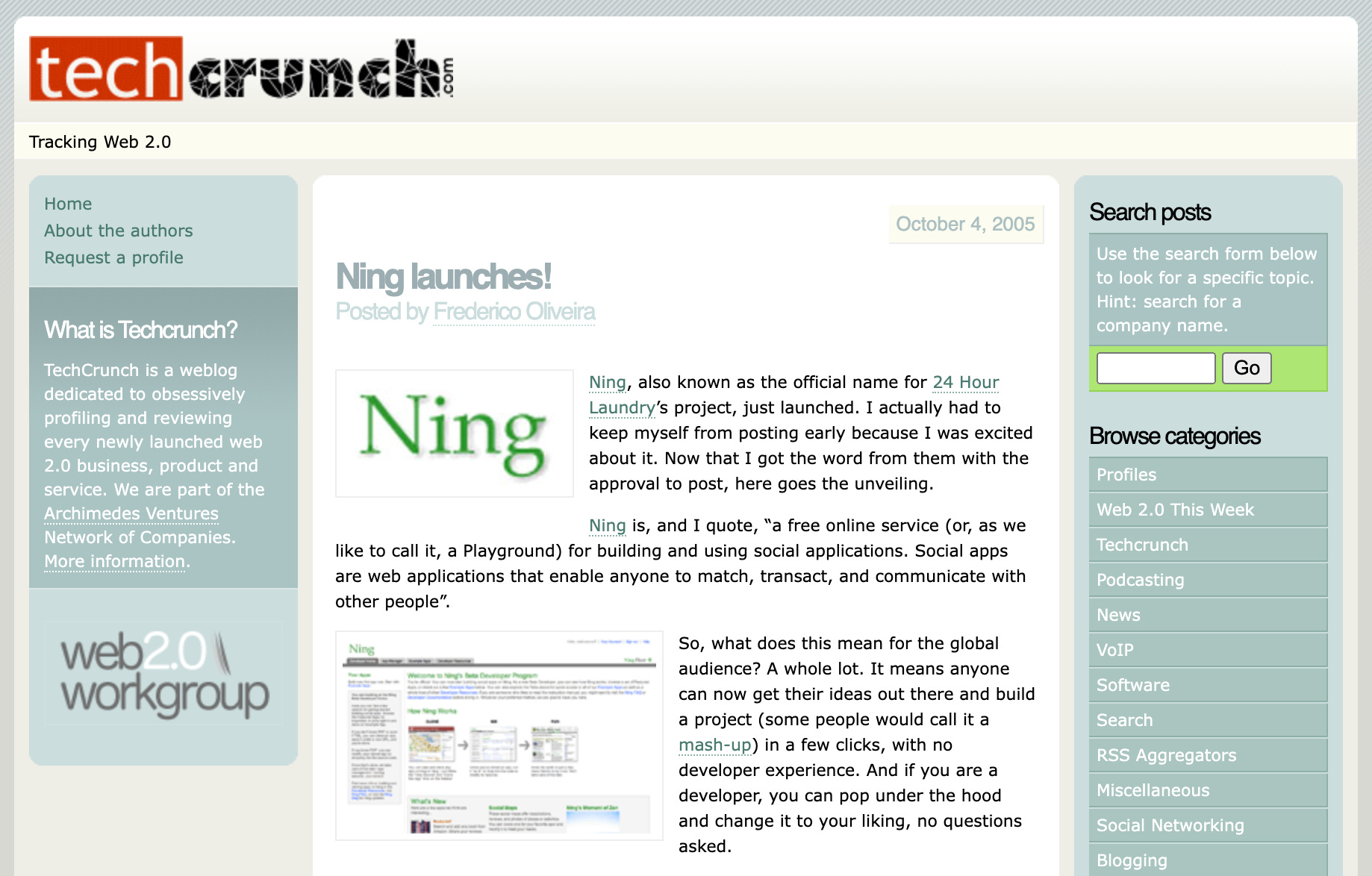

The news about Ning’s launch broke on Tuesday, October 4, 2005, on a relatively new tech blog called TechCrunch. It was the day before the start of the second annual Web 2.0 Conference, run by O’Reilly Media and to be held at the Argent Hotel in San Francisco. Andreessen wasn’t on the event schedule that year (he had attended the inaugural Web 2.0 Conference in 2004), but he and his co-founder Gina Bianchini took advantage of the Web 2.0 news cycle to launch their new company.

I was in town to attend the Web 2.0 Conference. The founder of TechCrunch, Michael Arrington, had kindly invited me to stay at his rented ranch house in Atherton, in the heart of Silicon Valley (a couple of years later, Andreessen would purchase a $16.6 million Tuscan-style mansion in Atherton). Mike had launched TechCrunch just a few months before my trip, and it had very quickly become the go-to blog for Web 2.0 news.

As soon as it launched, I’d reached out to Mike’s co-founder, a British expat named Keith Teare, noting that TechCrunch “looks like a great resource about Web 2.0.” Keith cc’ed in Mike, who immediately replied, saying, “I am a big fan of your website and have been using it for leads on TechCrunch.” We were similar ages — he was born the year before Andreessen and me — so we swapped emails and soon connected on Skype IM.

At the TechCrunch home office, 13 October 2005. From L to R: Fred Oliveira, Michael Arrington, Gabe Rivera from tech.memeorandum.

Since I was staying with Mike in his Atherton ranch house, I had noticed the TechCrunch post about Ning as soon as it went up. It had been posted in the early hours of Tuesday, about 1am — late-night blogging was all part of the adventure. The writer wasn’t Mike, but Frederico (Fred) Oliveira, a young developer from Portugal who was also staying at the TechCrunch ranch. Both Fred and Mike were friendly to me and I had felt an immediate camaraderie with them; we were “bloggers” and there was a lot of talk about Web 2.0 and the exciting startups that were emerging at that time, interspersed with rounds of Applewood pizza and watching episodes of South Park.

It had soon become clear to me that Mike was already an insider in this scene, by dint of his Atherton location and previous Dot Com experience (he’d been a lawyer for startups). He had some kind of direct access to either Andreessen or Bianchini, or both, which I didn’t yet have. Fred too had connected with at least one of Ning’s founders, opening his own blog post about Ning by writing, “Gina from 24 Hour Laundry just IM’d me giving me the green light to talk about their project.”

The TechCrunch Ning post (screenshot from 13 October 2005). Note the “Web 2.0 Workgroup” badge on the left — that was brand new. It was a group that me, Mike Arrington and Fred Oliveira launched while I was staying at the TechCrunch ranch.

After seeing the TechCrunch post, I wrote a quick post that linked back to it. I really had nothing to add, since I had not actually been given access to the product yet. But I wrote, “I can’t wait to have a play.” This initiated my first — and to this day, only — direct contact with Marc Andreessen. Soon after my post was published, I received the following email from him:

“Hi Richard – I read your blog – thanks for the kind words re Ning – if you haven’t been activated for a beta developer account already, please send me the email address you used to sign up and I will turn you on!”

Marc Andreessen read my blog?! At this point, I knew I had found my calling. I emailed him back saying I’d signed up. A couple of hours later, he confirmed that my account was activated.

I felt like I’d just joined the ranks of Silicon Valley’s insiders. And, as it turned out, tech bloggers were indeed the new nexus of Web 2.0.

This post is part of my serialized book, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley’s Web 2.0 Revolution. View table of contents.

Next up: 002. The Early Years of ReadWriteWeb

You're reading Cybercultural, an internet history newsletter. Subscribe for free, or purchase a premium subscription. Your support for this indie publication would be greatly appreciated.