What the Internet Was Like in 2010

2010 was the year of mobile apps — Instagram's launch, the rise of Foursquare, the release of the iPad, and the rapid growth of Facebook and Twitter via apps. The internet also impacted political uprisings.

The internet in 2010 was when social media conquered the world, as people flocked to Facebook and Twitter to have their say. Much of this was driven by smartphone apps—not just from the established players, but by newer apps like Instagram (the first truly mobile-native photo sharing app) and the location-based social networking app Foursquare.

In addition, 2010 saw the release of new forms of mobile devices—Android phones like the Nexus One, along with Apple's breakthrough tablet. The iPad's release in April was quickly followed by tablet-focused apps like Flipboard (a social reader), Zinio (magazines), Newsy (video news) and Brushes (finger painting!).

Mobile Apps Breakthrough

The culture flip to mobile was epitimized by the launch of a new iOS app in October, called Instagram. Its founders, Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger, had originally created an HTML mobile website called Burbn—where photo sharing was just one of the features. But the pair soon pivoted and turned that minor feature into its own product: Instagram. It was an immediate success. By the end of 2010, Instagram had a million users—a textbook example of a well-executed startup pivot.

Instagram eventually became the leading platform for influencer culture, but the beginnings of that trend were evident even before it launched. Throughout 2010, bloggers and YouTube users were increasingly marketing products on their blogs and video channels, as well as cross-pollinating their content across social media services like Facebook and Twitter. Indeed, for much of 2010 blogs were still at the center of the social web—even on YouTube, the emerging influencers were known as “vloggers.”

It's worth noting that although Instagram was iOS-only at first, over 2010 Android gained significant traction as a smartphone platform competing with iPhone. The most popular new Android phone that year was the Nexus One, which launched in January.

And let's not forget the iPad, which was released in April 2010. One of the first batch of apps developed specifically for Apple's new tablet was Flipboard, a "social magazine" app that launched in July. I interviewed founder Mike McCue a few months after, who told me that Flipboard initially had two different types of users—"there's the more social networking-oriented user and there's the RSS news reader type of user." An indication that RSS was still a key feature of apps in 2010, despite social media feeds gaining ascendancy.

Mainstreaming of Social Media

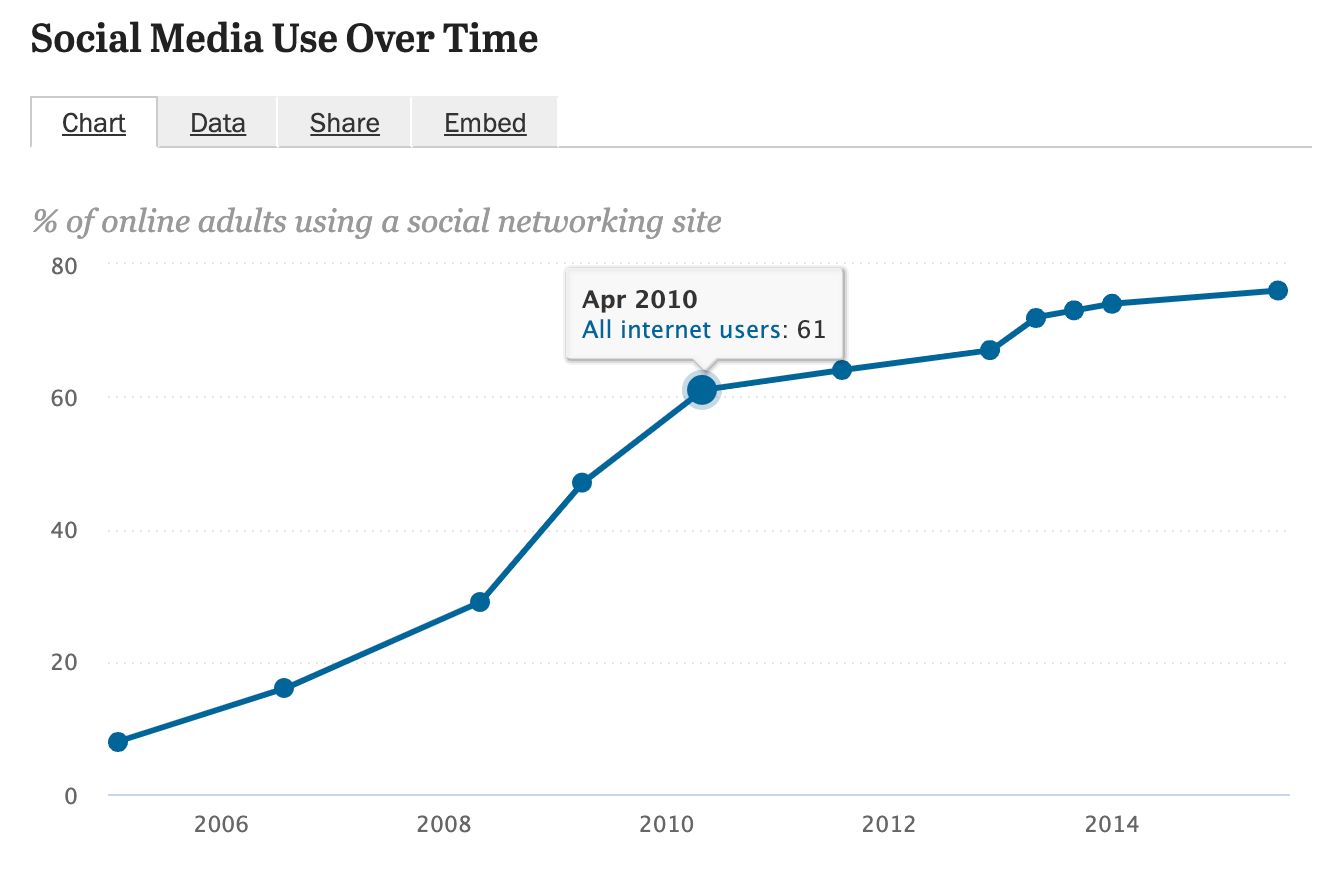

By May 2010, it was apparent that the social web was entrenched in the culture. A Pew Research report at that time found that more than half of Americans now used a social network.

The internet in 2010 was still controlled by Silicon Valley geeks, but it was also increasingly the scene of a vast cultural shift. It wasn’t just bloggers writing to the web anymore—it was everybody. And primarily they were adopting social media for that purpose.

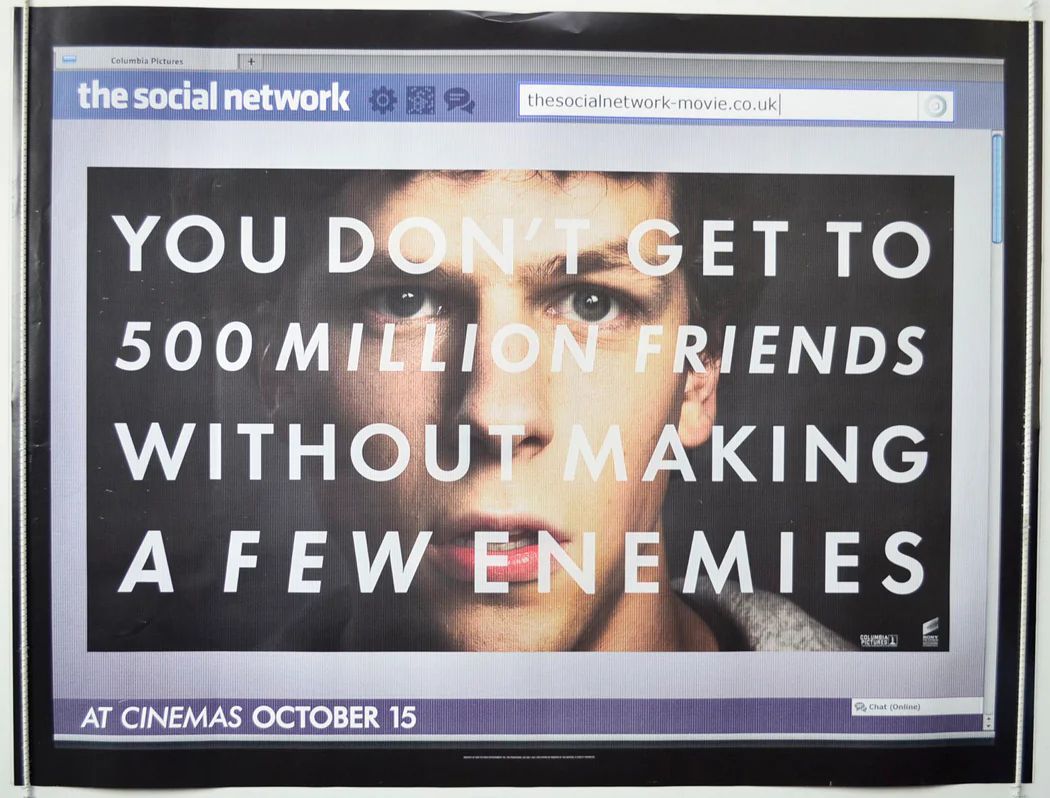

By July 2010, Facebook had passed five hundred million active users. But the real tipping point came in October, when Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook were immortalized in the culture with the Hollywood film The Social Network.

The mainstreaming of Twitter was more complicated. In September Twitter redesigned its home page, primarily to make it easier for non-tech people to consume content on Twitter. “You don’t have to tweet,” then Twitter CEO Evan Williams said at a press gathering, “any more than you have to make a webpage to use the Web.”

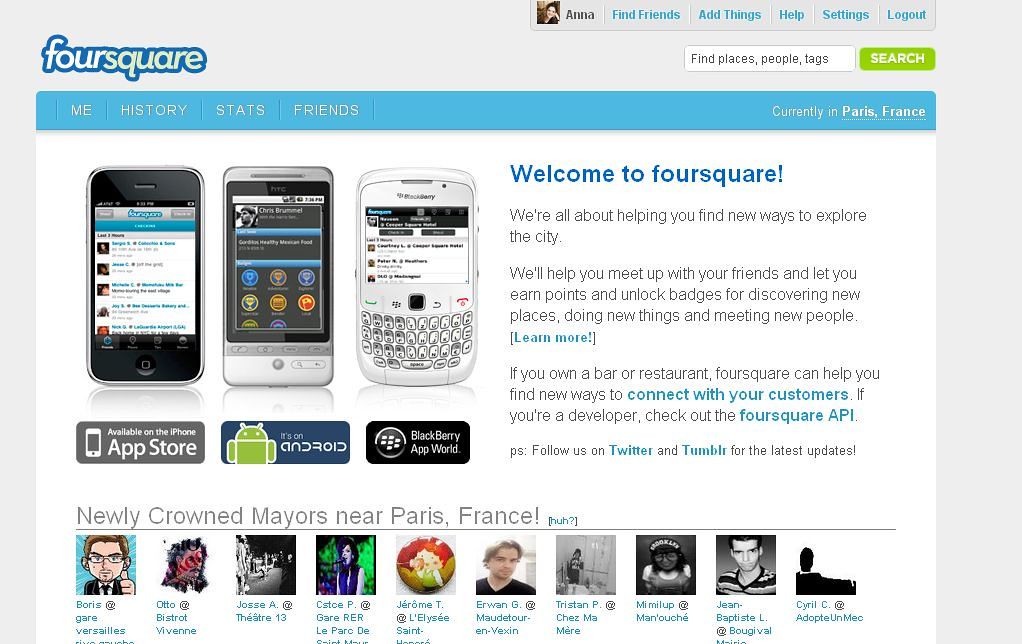

Location Social Networks

Foursquare, an app that encouraged you to "check in" to cafes, bars, parks—indeed, any place at all—became one of the trendiest Web 2.0 apps of 2010. For a time, there were multiple check-in apps competing for attention, including Gowalla and Brightkite. But Foursquare was the original and kept adding features to keep their users happy—for instance adding photos and comments to the product in December (remember Instagram only launched in October, so photo-sharing wasn't necessarily that common in mobile apps until then).

Many Foursquare users took pride in being the "mayor" of an establishment—the person who had checked in the most. I ended up checking into my favourite cafe, Go-Bang Expresso in Petone, New Zealand, 137 times. It was enough to be the mayor of that establishment for about three years, starting in August 2010. Being the mayor was a simple example of “gamification” in Web 2.0 apps—a way to keep users from doing otherwise pointless things on social media, like checking into a cafe 100 times.

Social Gets Serious

It wasn’t all fun and games. In China during 2010, there was an ongoing crackdown on Western internet apps.

In March 2010, I participated in a live event at the Paley Center for Media in New York City, alongside Chinese artist Ai Weiwei and Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey. Weiwei's description of internet censorship in his home country of China was sobering. He noted that people in China could not use Twitter, YouTube, or Facebook, and that Google might soon be added to that list. “Basically, it’s a society which forbids any flow of information and of freedom of speech,” Weiwei remarked. He explained that even though the Chinese internet had lots of clones of Western apps, their usage was closely monitored and censored by the government.

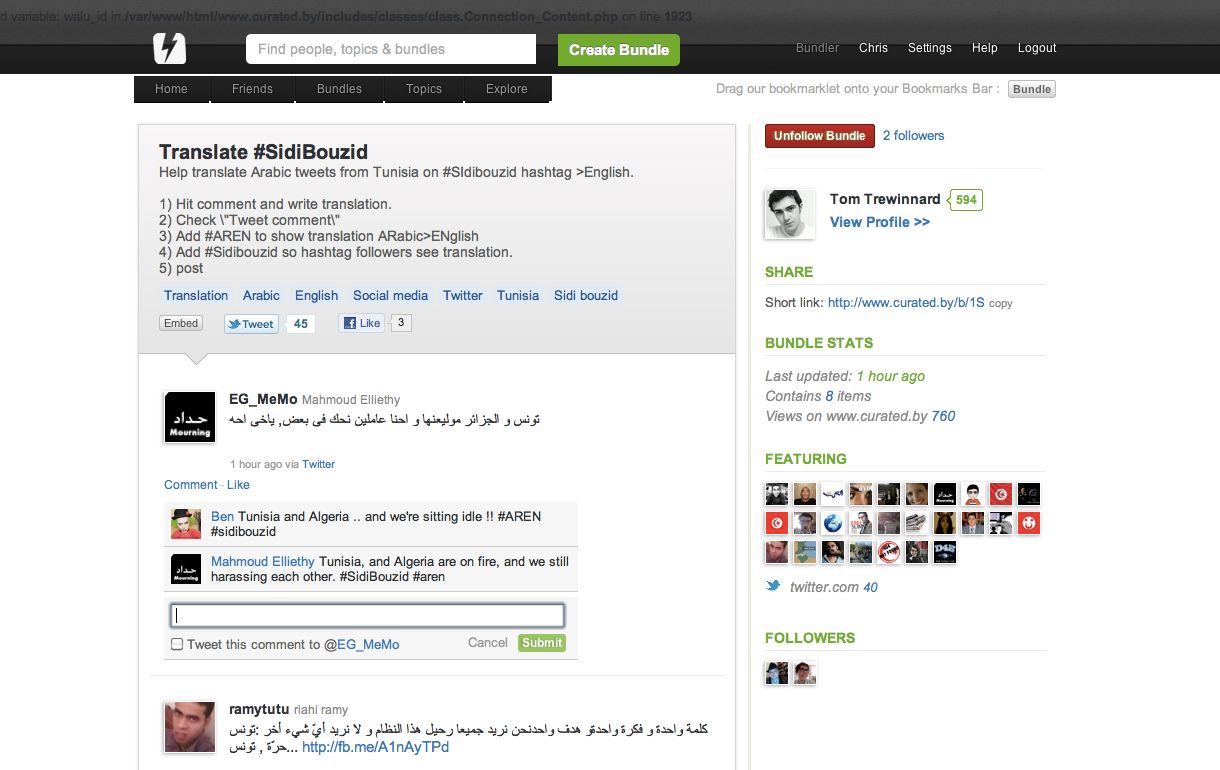

Meanwhile, towards the end of 2010 a series of protests against government oppression began across the Middle East and North Africa. It became known as the "Arab Spring" and internet technology—particularly the use of mobile apps like Twitter—was a key part of the uprising.

One of the first series of protests was in Tunisia, starting in December 2010 when a young Tunisian, Mohamed Bouazizi, set himself on fire to protest living conditions in his country. As ReadWriteWeb's Curt Hopkins reported: "On Twitter, the coverage has been hashtagged #sidibouzid, for the city Bouazizi killed himself in and where the protests started. Additional tags have included #jasminrevolution and, for the hacktivist actions against the government's websites by Anonymous some are using #optunisia."

For all the fun things that the social web and smartphones apps enabled in 2010, there was a serious side to these technologies too. The rest of the decade would certainly prove that out, as platform power asserted itself on the internet and privacy issues proliferated.

Lead image: Photo by Scott Beale / Laughing Squid; some pixelation applied by author.

Read next: More year-by-year overviews of internet history

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.