What the Internet Was Like in 1997

In 1997, the first browser war began amid new internet trends like 'push' and DHTML. Meanwhile, instant messaging apps like ICQ and AIM became popular and GeoCities achieved 1 million users.

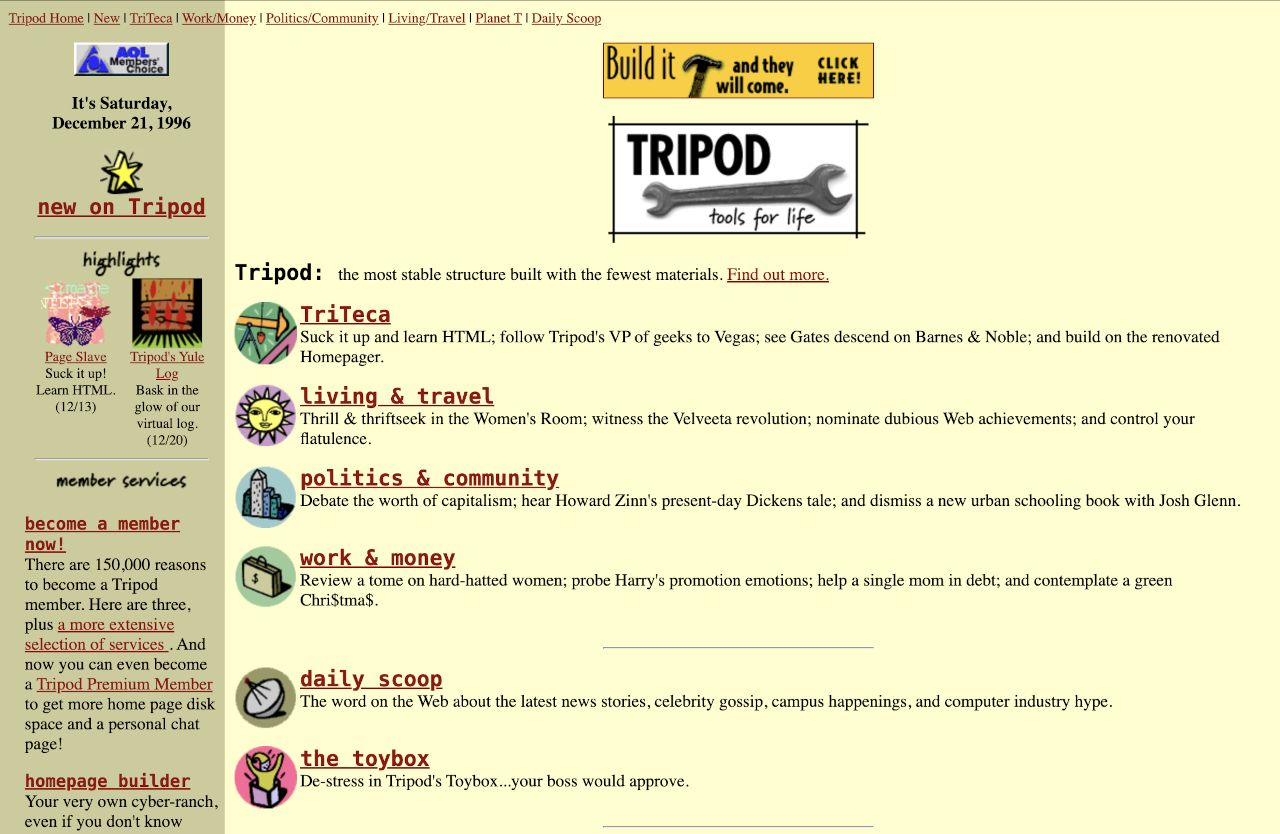

In 1997, the World Wide Web finally went past 1 million websites — with over 120 million internet users. As the number of websites went up, the range of sites blossomed too. Over a million people built personal home pages on GeoCities, Tripod and Angelfire. And while the Web had only just gone multimedia a few years before, now it was pushing the limits with technologies like Flash, Java applets and streaming media.

Web commercialism also ramped up over 1997. While the dot-com boom was still in its early stages, notable IPOs this year included Amazon.com in May, N2K in August and RealNetworks in November. Meanwhile, Wired Magazine — Silicon Valley's bible — declared in July that "we're facing 25 years of prosperity, freedom, and a better environment for the whole world." Wired called this the beginning of "the long boom." Clearly, things were looking up for the internet.

Browser War

Despite the rising tech-optimism of 1997, the underlying web platform was still in flux. The two main web browsers, Netscape Navigator and Microsoft Internet Explorer, began to diverge in how they implemented web technologies like HTML, CSS and JavaScript.

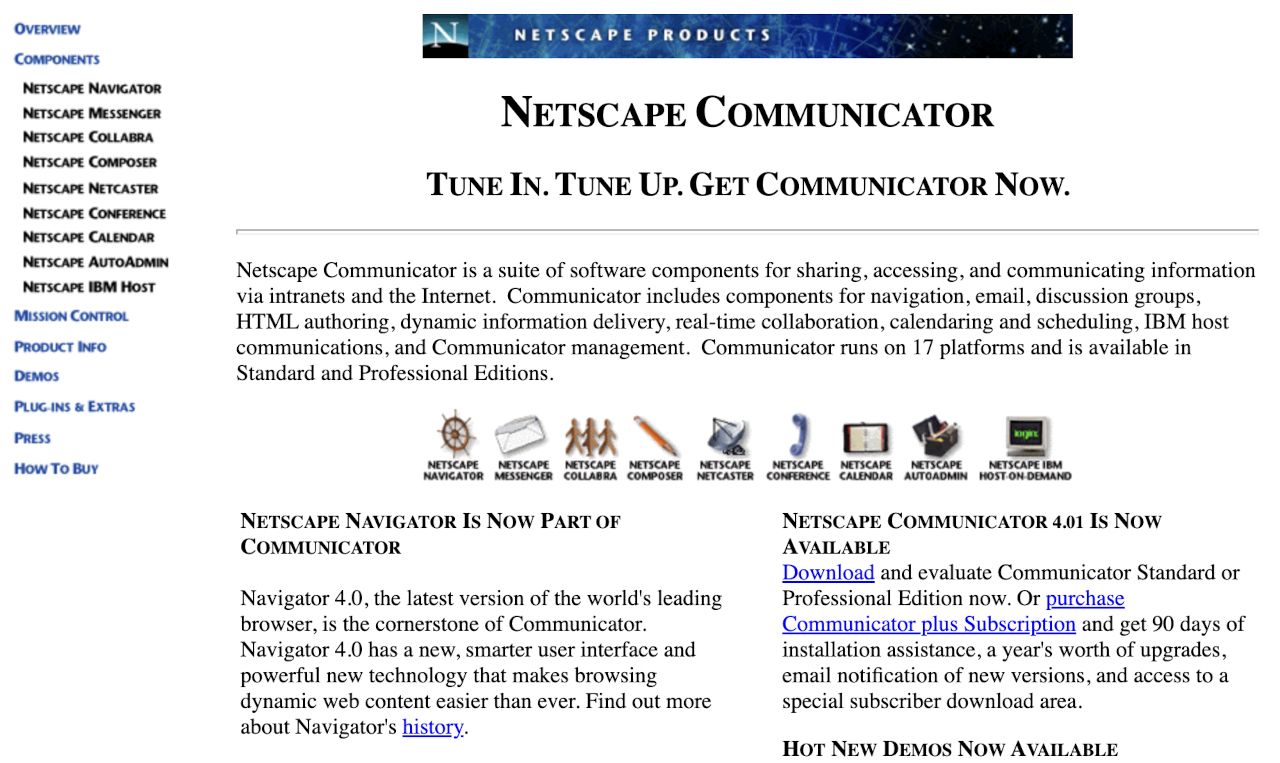

Web users in 1997 also discovered that the browser was now just the start of what was being offered to them. Netscape launched a suite of products called Netscape Communicator in June 1997. As well as Navigator 4.0, it included integrated email, calendar, newsgroups, a webpage builder, and other features.

When Microsoft's Internet Explorer 4.0 was released as a preview the following month, as well as the core browser it promised "a complete communication and collaboration solution, and true Web integration." (The "integration" part would soon attract the interest of the US Justice Department, as it meant integration with the Windows operating system.)

Push!

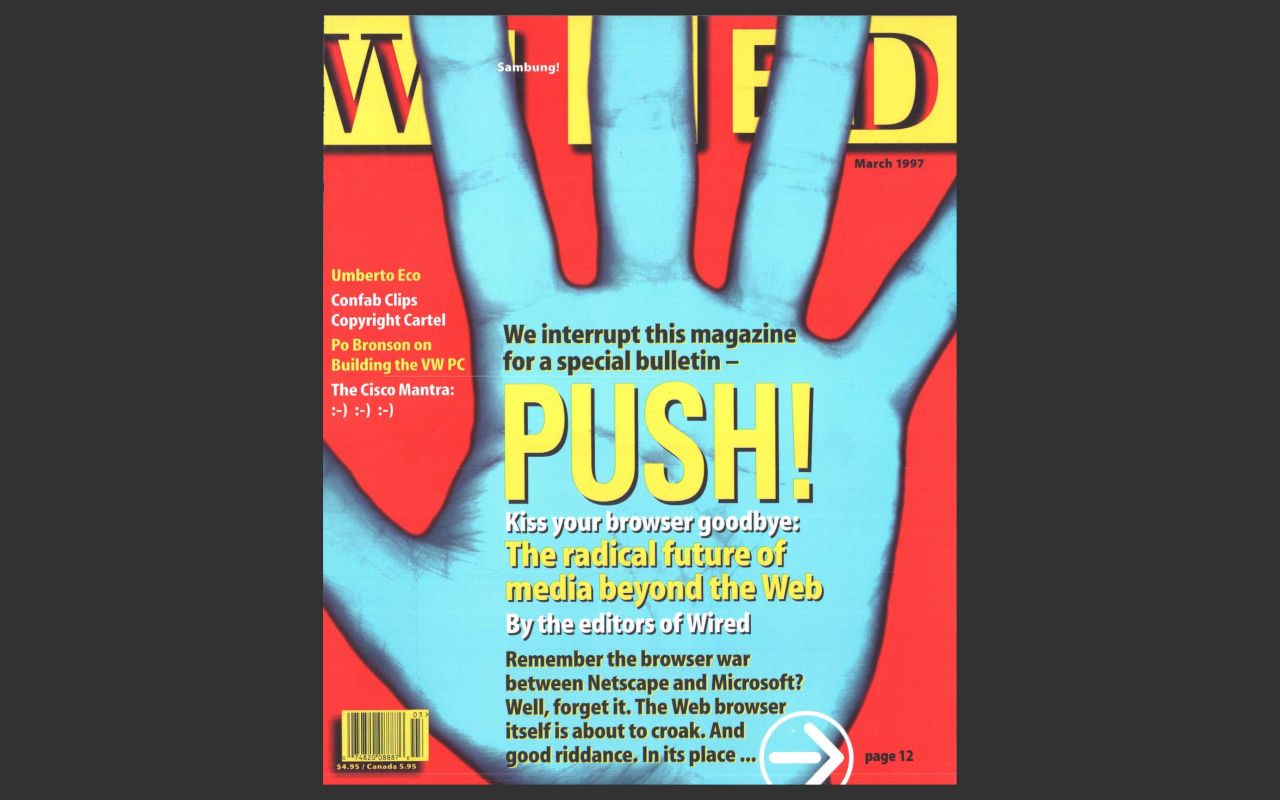

A web browser allows you to 'pull' information from the World Wide Web onto your computer. 'Push' technology was the opposite — you would subscribe to certain types of information and it would be delivered from a server onto your computer. In March 1997, Wired Magazine claimed that "you can kiss your browser goodbye," because push technology — as touted by PointCast, BackWeb and similar companies — would be the future of internet media. Never shy to ramp up the hype, Wired's cover that month stated:

"Remember the browser war between Netscape and Microsoft? The Web browser itself is about to croak. And good riddance."

However, in the main article, Wired struggled to define what exactly push was: "...anything flows from anyone to anyone - from anywhere to anywhere - anytime." Okaaaay. How Wired described PointCast also didn't sound very enticing:

"The 1.7 million downloaded copies of PointCast demonstrate how a gentle push works. When your computer is idle, PointCast uses the Web to push news bits (of your choice) and advertising onto your screen in a slow parade. If your attention is grabbed, you can click to pull up an expanded version."

So push was...a new way for adverts to be delivered electronically?

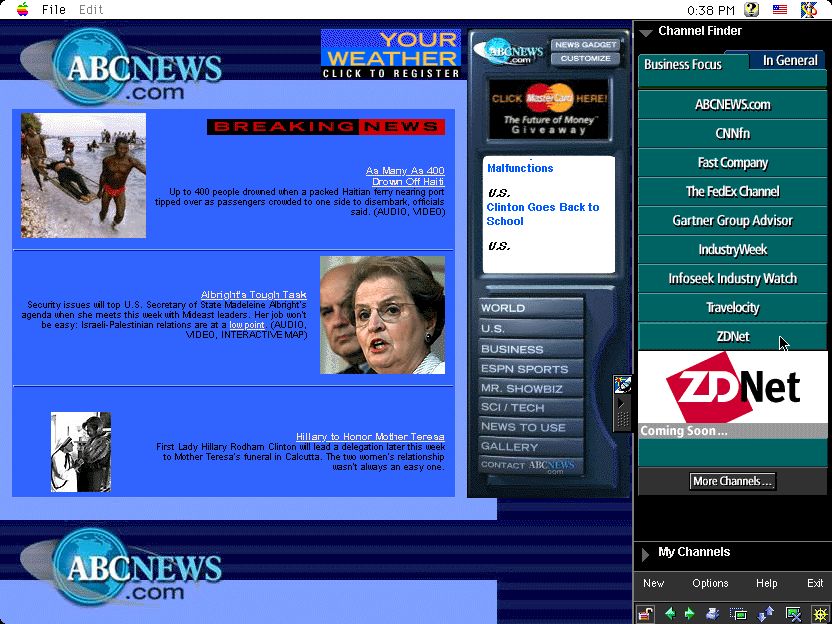

Despite the amorphous hype around push technology, the browser companies quickly adopted it — calling it "channels" instead. "Active Desktop" was the Microsoft version and Netscape had a product called Netcaster, which was bundled with Netscape Communicator 4.0. Here's how CNN described Netcaster in an April 1997 article:

"Through Netcaster, users will be able to subscribe to and receive information from leading content providers through dynamic Web channels."

But both Microsoft and Netscape used HTML to deliver these features, proving that Wired's 'death of the browser' pronouncement was woefully wrong.

In any case, push turned out to be a short-lived phenomenon — when Netscape debuted RSS (RDF Site Summary) a couple of years later, that killed off push. PointCast was also nearly dead by then.

DHTML

The browser companies were not immune to hyping up new buzzwords in 1997.

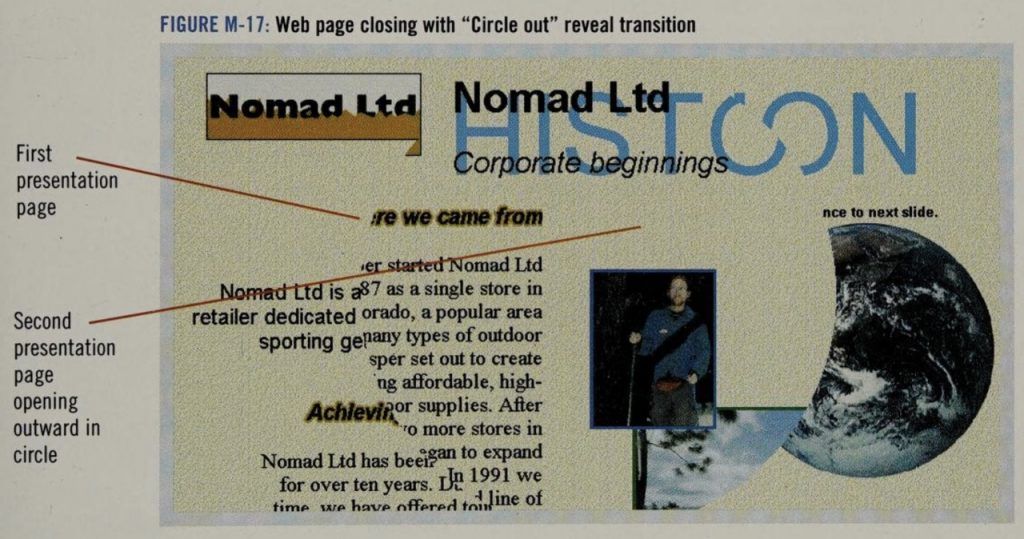

DHTML, or Dynamic HTML, was essentially a combination of HTML, JavaScript, the newly released CSS standard, and an emerging web programming model called the DOM (Document Object Model). However, the precise definition of DHTML depended on which browser company you spoke to: Netscape or Microsoft.

As it turned out, Microsoft’s vision for DHTML was more compelling from a technical perspective than Netscape’s. Microsoft set out to make every element of an HTML document into a programmable object. JavaScript was, at the time, focused on the interactivity of forms and images. Microsoft’s DHTML, though, expanded the canvas for interactivity to the entire web page.

In comparison, Netscape's version of DHTML was limited to the positioning and layering of certain elements of a webpage.

Nowadays we don’t use the term “DHTML” and much of the interactive functionality that it promised in 1997 became subsumed into the W3C DOM standard, which debuted the following year.

Personal Home Pages

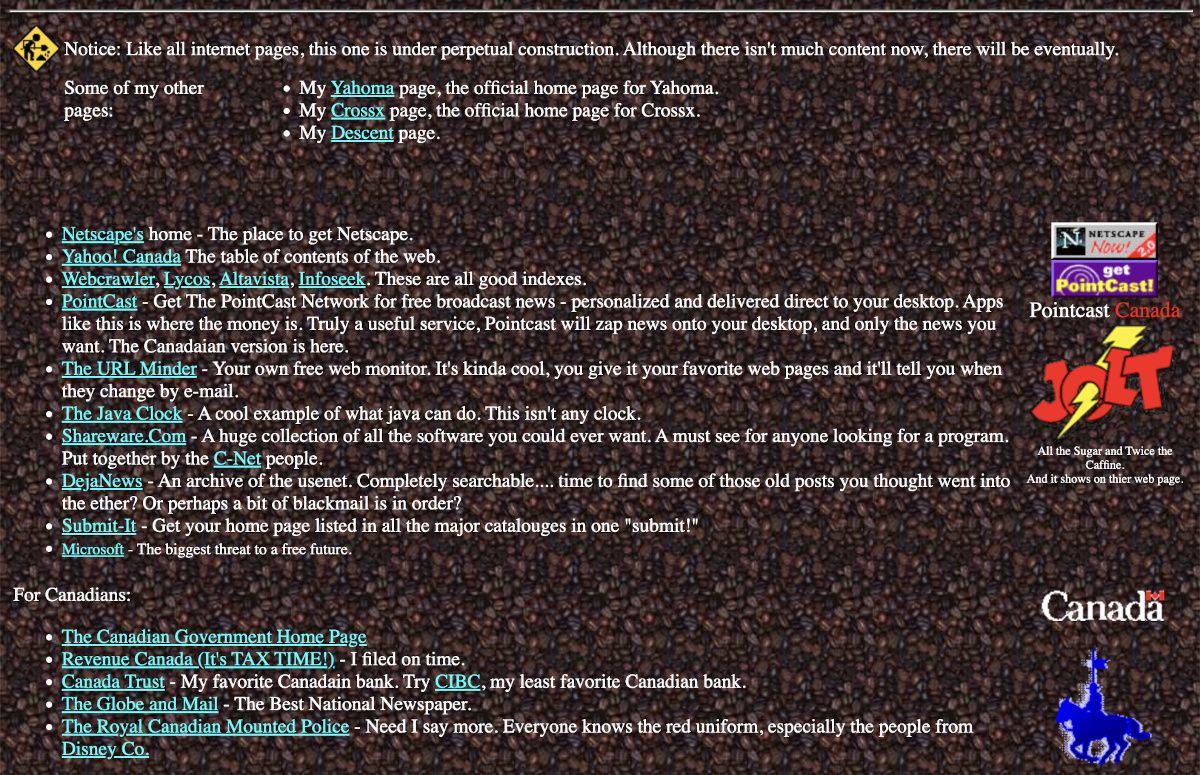

Aside from the expansion of web technologies over 1997, the use of personal home page tools like GeoCities, Tripod and Angelfire also rapidly increased. In October 1997, GeoCities announced that it had "registered its one millionth 'homesteader' since the company opened its doors in June of 1995."

(At first glance, this statistic seems to contradict the 1 million websites figure that I quoted in the opening paragraph. My guess is that internetlivestats.com only counted GeoCities as one website in 1997, since it defines "website" as a "unique hostname".)

Conveniently, it was a teenager who was purportedly the one millionth user of GeoCities:

"The event, a unique milestone among Web sites, occurred at exactly 6:00 PM (Pacific Time) on October 2 when a 16-year old girl from St. John, New Brunswick, Canada completed the construction of her own personal home page."

Designwise, most GeoCities home pages tended to feature colorful backgrounds, animated GIFs, and autoplaying MIDI music. "Under construction" signs proliferated and many home pages used frames to divide content into scrollable sections. Popular features included hit counters and guestbooks.

As GeoCities scholar Olia Lialina later quipped, "already in 1997 in web design cicles 'Geocities' was a swear word."

Instant Messaging

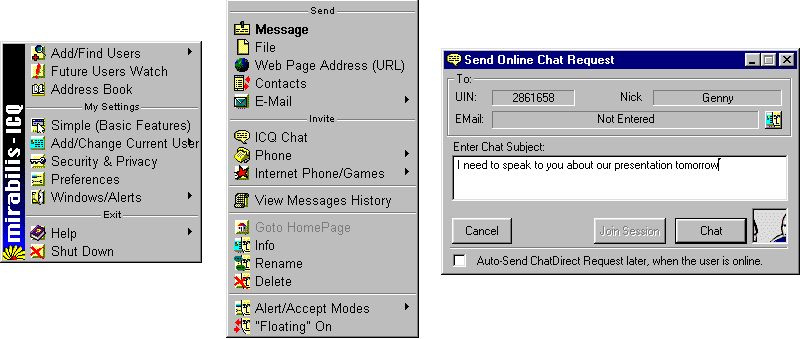

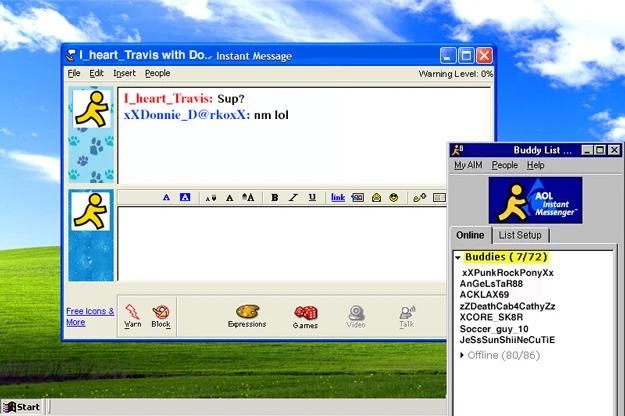

Finally, instant messaging was a noteworthy trend in 1997, thanks to ICQ and AOL Instant Messenger (AIM). Both were internet apps that you downloaded onto your computer and which let you chat one-on-one or in small groups in real-time. They featured buddy lists and notifications when one of your friends came online.

Earlier messaging systems like IRC and Usenet newsgroups had often started as text-based protocols, although they later adapted with graphical clients. But since ICQ and AIM were designed from the ground up as standalone GUI apps, they were more intuitive and approachable for everyday users.

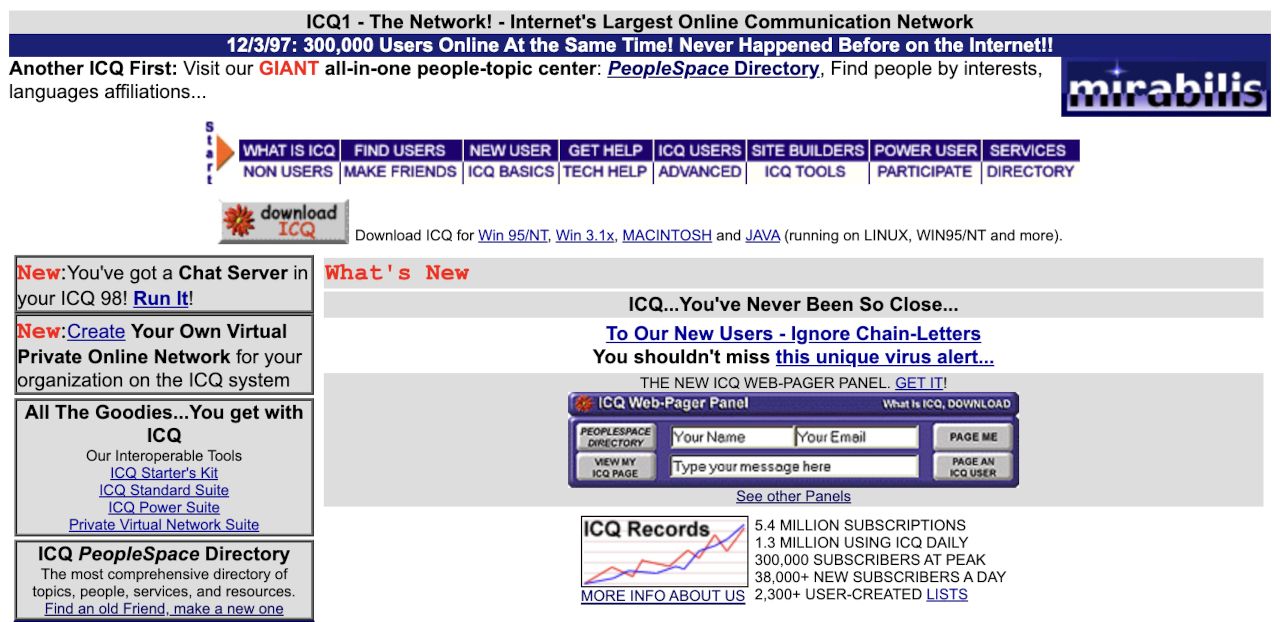

ICQ was the first of the pair to launch, in late-1996, and grew fast over 1997. Its parent company, Mirabilis, described the product as "a revolutionary, user-friendly Internet tool that informs you who's on-line at any time and enables you to contact them at will."

AOL already had chat functionality, but it wasn't until May 1997 that it launched AIM as a separate app for Microsoft Windows.

Even though ICQ had first-mover advantage, AOL ended up winning the IM market — it acquired Mirabilis the following June.

Overall, 1997 was quite a diverse year in terms of internet products (IM apps, push, home page builders, etc.) and the underlying technology (browser expansion, DHTML).

To read about other years in internet history, click here.

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.