GeoCities in 1995: Building a Home Page on the Internet

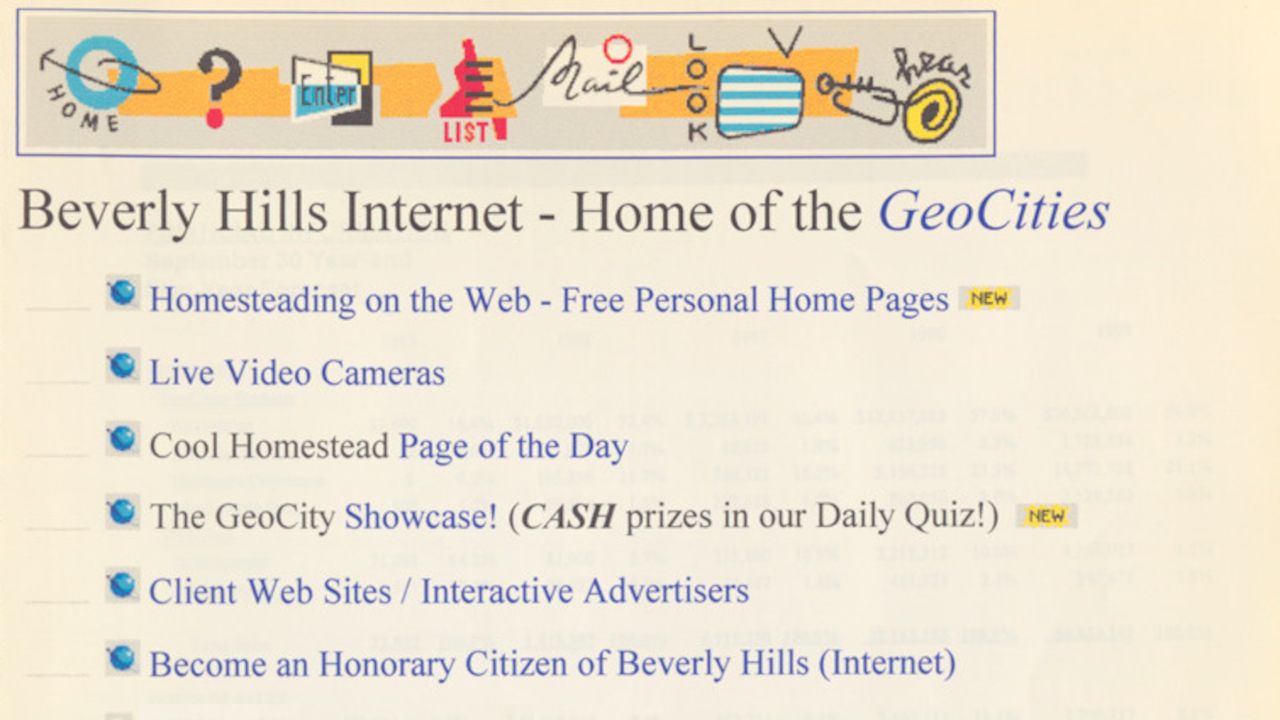

GeoCities, known throughout most of 1995 as Beverly Hills Internet, was one of the first commercial internet services to make it easy for people to publish a home page on the World Wide Web.

By 1995, people had begun to create their own web pages on the World Wide Web — or “home pages” as they were called back then. Previously, home pages had typically been created by professional coders, or academics who had technical knowledge of the web. Not only did you need to know how to code in HTML, the web’s programming language, but you also needed to know how to operate web servers and FTP (File Transfer Protocol) software.

But as the web became more popular, consumer-friendly tools emerged to help people create a home page. Beverly Hills Internet (BHI), later renamed GeoCities, was one of them.

GeoCities had been started in late 1994 by David Bohnett and John Rezner. Initially it was a web hosting service named Beverly Hills Internet (www.bhi90210.com), because that’s where Bohnett lived and worked. After getting some local businesses up and running with their first webpage, he began to think of what he could offer beyond web hosting.

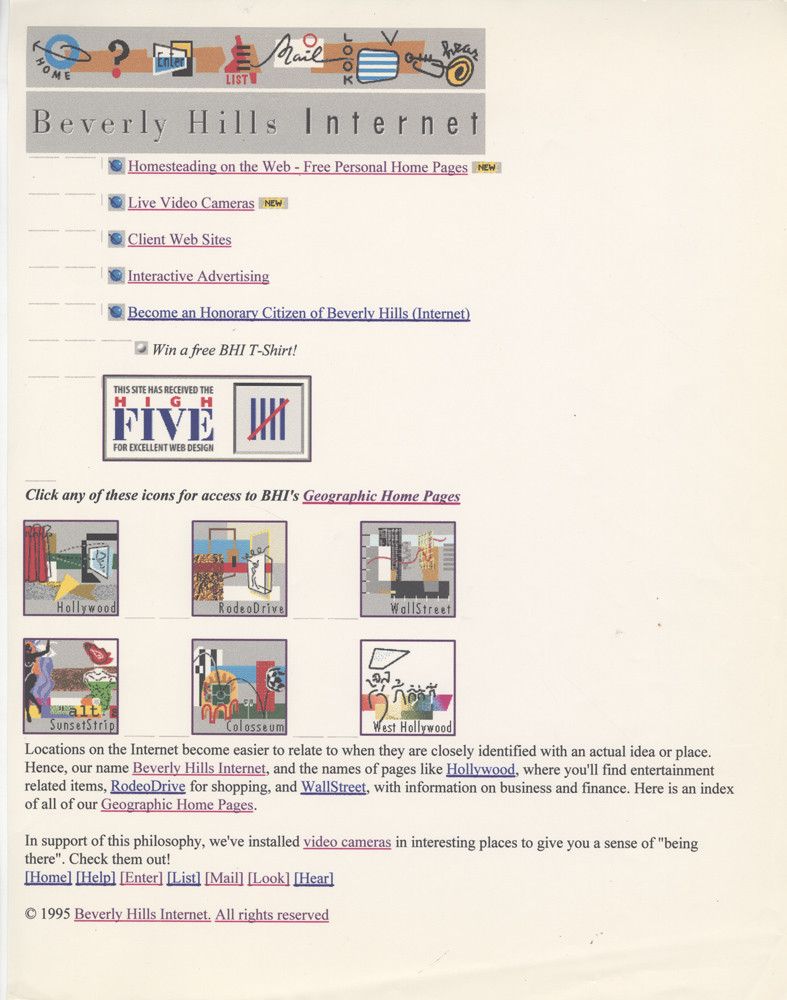

Bohnett then set up a couple of webcams, one at his Beverly Hills office and the other at the Hollywood office of a friend. This brought in a bit of traffic, which gave him the idea to offer free home pages to people based on those locations. For the webcam in Beverley Hills, people could set up a web page based around shopping. And for the Hollywood webcam, people would be able to create a fan page for a celebrity — or any entertainment product. These two “cyber cities” were called RodeoDrive and Hollywood.

Four other location-themed communities were added soon after: SunsetStrip (music and nightlife), WallStreet (business), the Colosseum (sports), and WestHollywood (for the gay and lesbian community — Bohnett is gay).

A Home on the Internet

In July 1995, Beverly Hills Internet (BHI) announced another four “virtual communities based on real-world locations” — SiliconValley (for technology), CapitolHill (for politics), Paris (for the arts) and Tokyo (for anime and “all things Asian,” according to Blade’s Place). By this time, the young company had begun to name these communities “GeoCities.” They’d also appropriated the term “Homesteader” to denote a person who published a web page on the service.

The key to BHI's initial growth over 1995 was helping people who had no technical knowledge of HTML to build a web page on the internet. It offered a “Personal GeoPage Generator” that enabled homesteaders to easily create a home page. But more than that, and as the name for its users implied, Bohnett wanted to give people the sense that they had a home on the internet.

“You may surf the net via access utilities or online services but you'll live in BHI's GeoCities,” he said in a press release. “There, on the street or in the city of your choice, you'll dwell in a home that reflects the context of your life, become part of the fabric of the community and establish your own net culture.”

Bohnett was perhaps the first web entrepreneur with the gift of the gab for marketing. Essentially he was offering a way for people to create a web page on the internet, but he spun that basic idea into an elaborate geographic metaphor. When a new user joined a community, they were even given a “street number” for their virtual neighbourhood.

“This is the next wave of the net — not just information but habitation,” said Bohnett.

GeoCities Design

When we look back on GeoCities today, we often think about all the quirky elements that made up a GeoCities web page in the 1990s: the animated GIFs, the garish colours, the cartoon fonts, the “Under Construction” icons. But in 1995, when the site was still known as Beverly Hills Internet, the web pages were relatively sparse.

Olia Lialina, an internet artist from Germany and co-founder of the GeoCities Research Institute with Dragan Espenschied, has studied the early web more than most. On the project’s blog, One Terabyte of Kilobyte Age, Lialina commented that many of the GeoCities pages archived from 1995 had design features in common, including “‘Under Construction’ and ‘Cool Links’ ribbons down the page, and the red bullet opening the ‘Links to other sites on the web’ section.” Horizontal bars were also common to these early pages, along with a limited selection of icons (small, usually square, image files).

Lialina concluded that these common design elements were the result of a template, via BHI’s “Personal GeoPage Generator.” She spoke with Bohnett about this and he described the generator as “a sample page, that one could edit in browser, by filling in text into the forms and by choosing icons, rulers and bullets from the menus.” The icons available were the result of Bohnett “surfing the web and saving items that would in his opinion match the expectations of the first webmasters.” Many of these early icons were national flags, but there were also things like an image of Dr Spock from Star Trek, Grover from Sesame Street, Calvin from the ‘Calvin and Hobbes’ cartoon strip, a newspaper icon, a bomb icon, and so forth.

Most BHI web pages from 1995 were relatively simple in construction and featured the elements noted above. The selection of images and icons became more extensive over time, while users also began to experiment more with web design. Another factor was the introduction of interactivity to websites at the end of 1995, when JavaScript debuted in Netscape Navigator 2.0 in December.

But it would take more time for scripting to infiltrate into GeoCities home pages. As Lialina told me on Mastodon, "stylewise, the most significant thing about "Geo1995" in contrast to widely celebrated "Geo1996" is that the pages were very close to the sample page David Bohnett put online some time in between May and July 1995."

GeoCities Legacy

In December 1995, BHI changed its name to GeoCities (although its web address was initially www.geopages.com). By this point, there were fourteen different geographic-themed communities and the service had attracted more than 20,000 users since its launch in June.

GeoCities went on to become hugely influential over the rest of the 1990s. However, we have to remember that ultimately it was a centralized platform that put certain dimensions around the creativity of those early web users. Other, similar, web hosting services would emerge during the mid-to-late nineties, such as Tripod, Angelfire and Homestead.

If you knew how to set up a web server and do HTML coding, you could of course create your own website outside of those services. As Lialina put it in a later blog post, “the point about the web before social networks or before Web 2.0 is not that you had a profile on GeoCities, but that you had a chance to build your cyber home outside of it, you could exist and grow outside of a centralized service.”

Lialina claims that GeoCities was not even a very good web hosting service. “It was free and not worse than others,” she wrote, and “that’s why webmasters endured the pain of clumsy page builders, interventions from commercial scripts being injected into their pages, accidental file deletions, etc.”

Regardless, the emergence of GeoCities over 1995 did make it easier for non-technical people to create a presence on the World Wide Web. Its design elements were certainly clunky and destined to become clichéd, but services like GeoCities were an important stepping stone for the rise of creative expression on the web.

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.