Cyberculture 1960s-1990s and the Legacy of Alice Mary Hilton

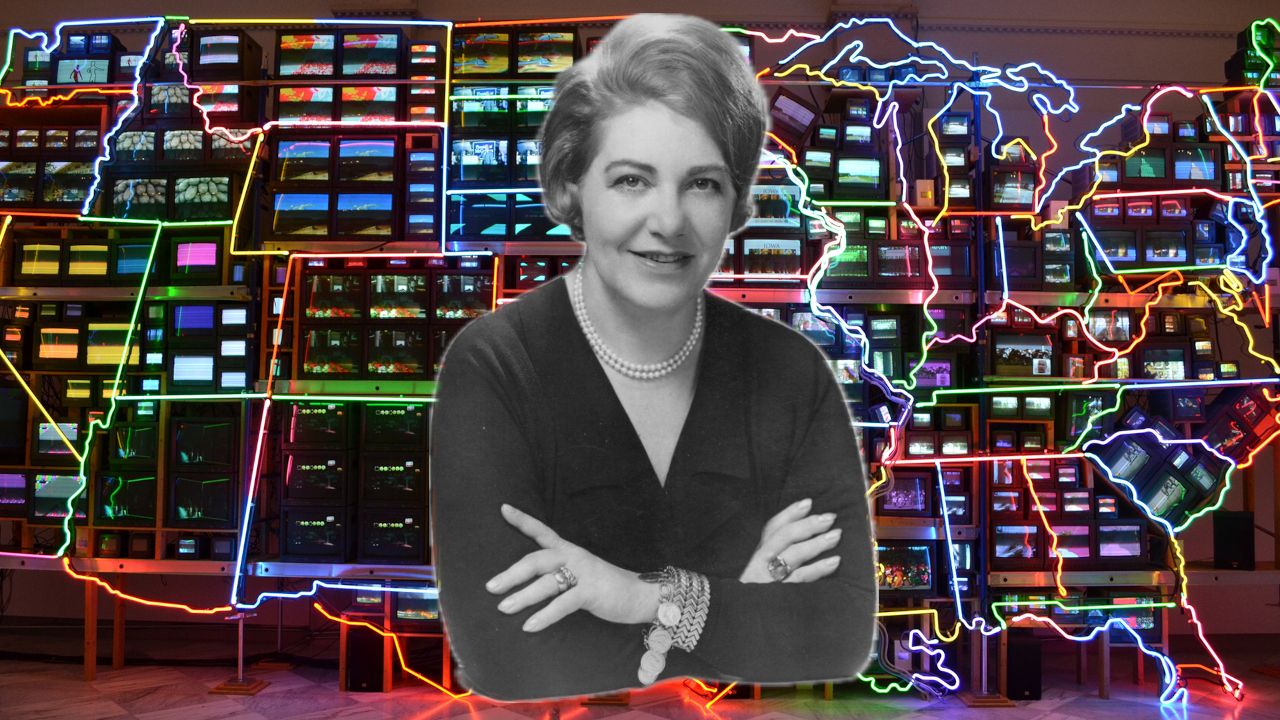

The word 'cyberculture' was coined by Alice Mary Hilton in 1963 and by the mid-90s was in common use. But Hilton never got her due, especially compared to her contemporary Marshall McLuhan.

If you search for “cyberculture” today in Wikipedia, you are re-directed to the page for “Internet culture” — which rightly indicates that the internet is now just a normal part of culture. But if you go back 30 years, to 1995, the word "cyberculture" was part of the online vernacular. Perhaps only in niche circles, but you’d have come across it if you read tech zines like Wired or bOING-bOING, if you were a sci-fi enthusiast who liked cyberpunk authors, or if you were an academic in the field of media theory.

The Origins of Cyberculture

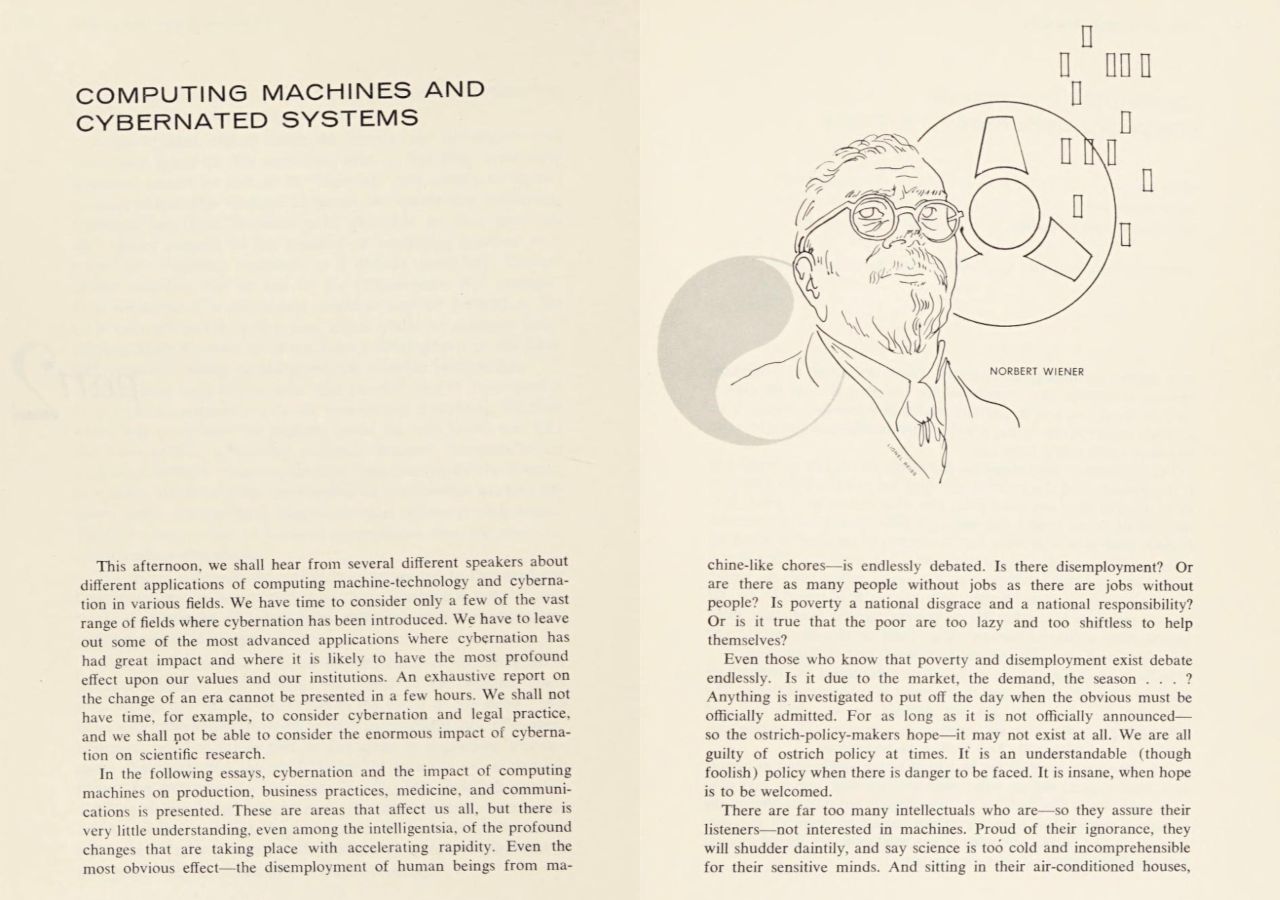

Although Wired and similar publications adopted cyberculture as part of their panoply of technobabble keywords, it was actually coined decades before. The origin dates back to the late-1940s, when the academic discipline of cybernetics was invented. Cybernetics is the study of feedback mechanisms in nature and technology. Its most famous progenitor was Norbert Wiener, who published a book in 1948 entitled Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. In that book, Wiener explains:

“We have decided to call the entire field of control and communication theory, whether in the machine or in the animal, by the name Cybernetics, which we form from the Greek κυβερνήτης or steersman.”

We then have to fast forward 15 years to come to the person who specifically coined the word “cyberculture”: Alice Mary Hilton, an accomplished British-American academic in her early-40s.

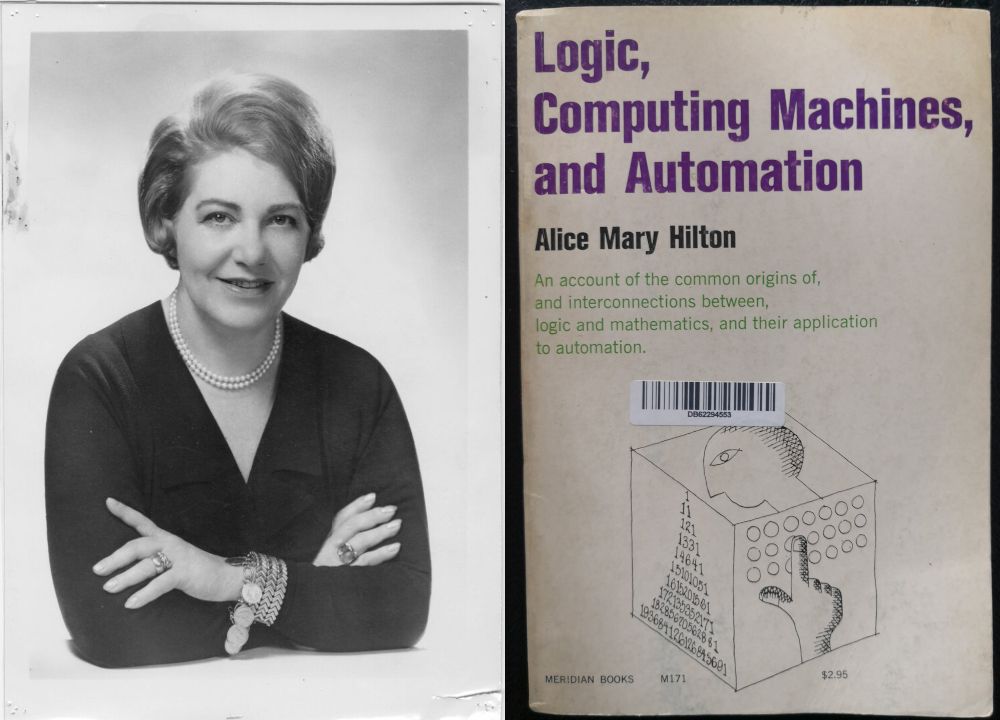

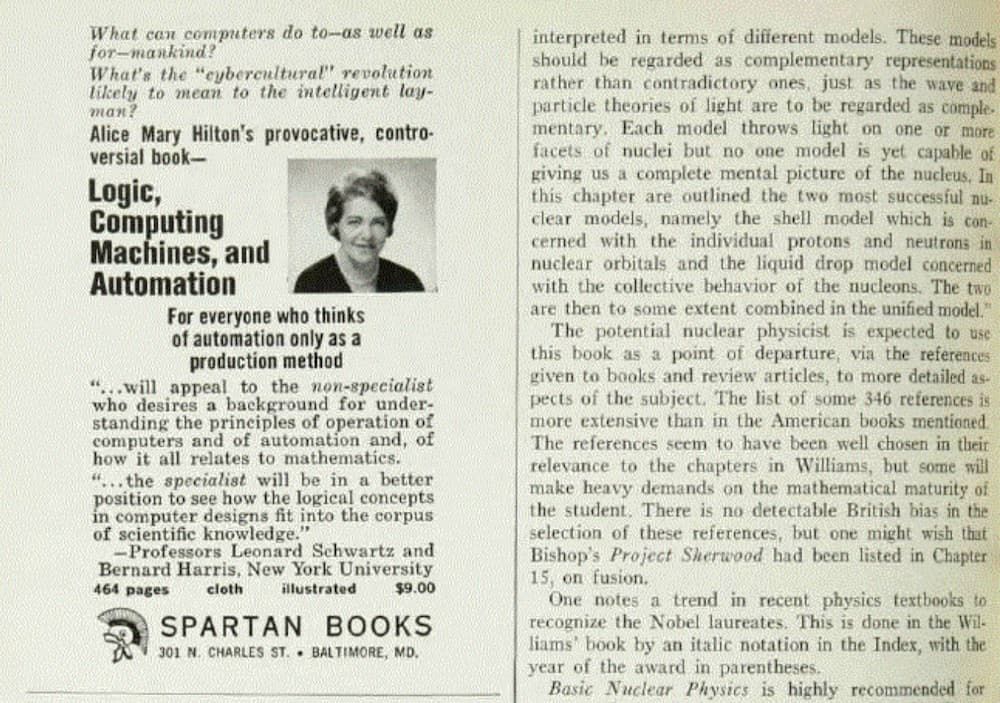

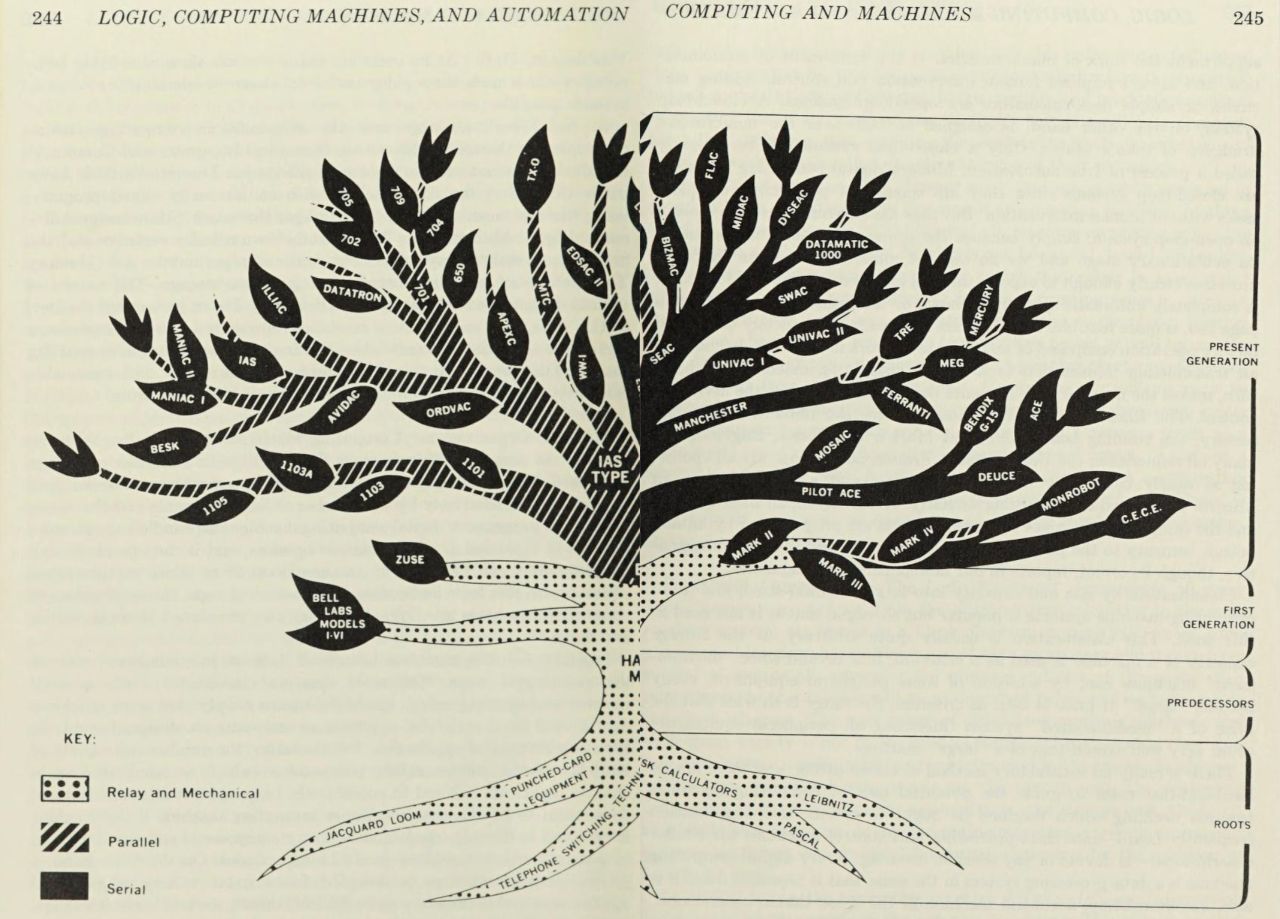

In 1963, Hilton published a book entitled Logic, Computing Machines, and Automation. The book described an emerging era of automation by “computing machines” — which in the early 1960s meant expensive business machines sold by the likes of IBM and Burroughs. Hilton felt that she had to invent a new word to describe her focus. The word she chose was inspired by cybernetics, but her concerns were less theoretical and more focused on the practical impacts of computer automation on society:

“The word "automation," in its broadest sense, encompasses far more than the commonly used, narrow definition implying more or less "automatic", i.e., machine-directed, production methods. Reluctant as I am to add to the deluge of new terms, I do not find an existing word for this vast new phenomenon with all its ramifications, i.e., the socio-economic and cultural aspects of the scientific-technological revolution in progress, and I shall call it the cybercultural revolution. In the word "cyberculture”, cybernetics, the science of control, and culture, the way of life of a society, are combined.”

The following year, Hilton founded The Institute for Cybercultural Research, a forum to discuss computers and the future of work. [1]

Hilton and McLuhan

Alice Mary Hilton’s focus on computerised automation can make for uncomfortable reading today, when generative AI threatens to automate many human jobs out of existence. When she writes in 1963 about “the emancipation of human beings from the need to do repetitive tasks, which can now be delegated completely to machines,” that’s a little too on-the-nose in 2025. So she was oddly prescient about the AI era we’re now living through, even though the references to mainframe computers are now very outdated.

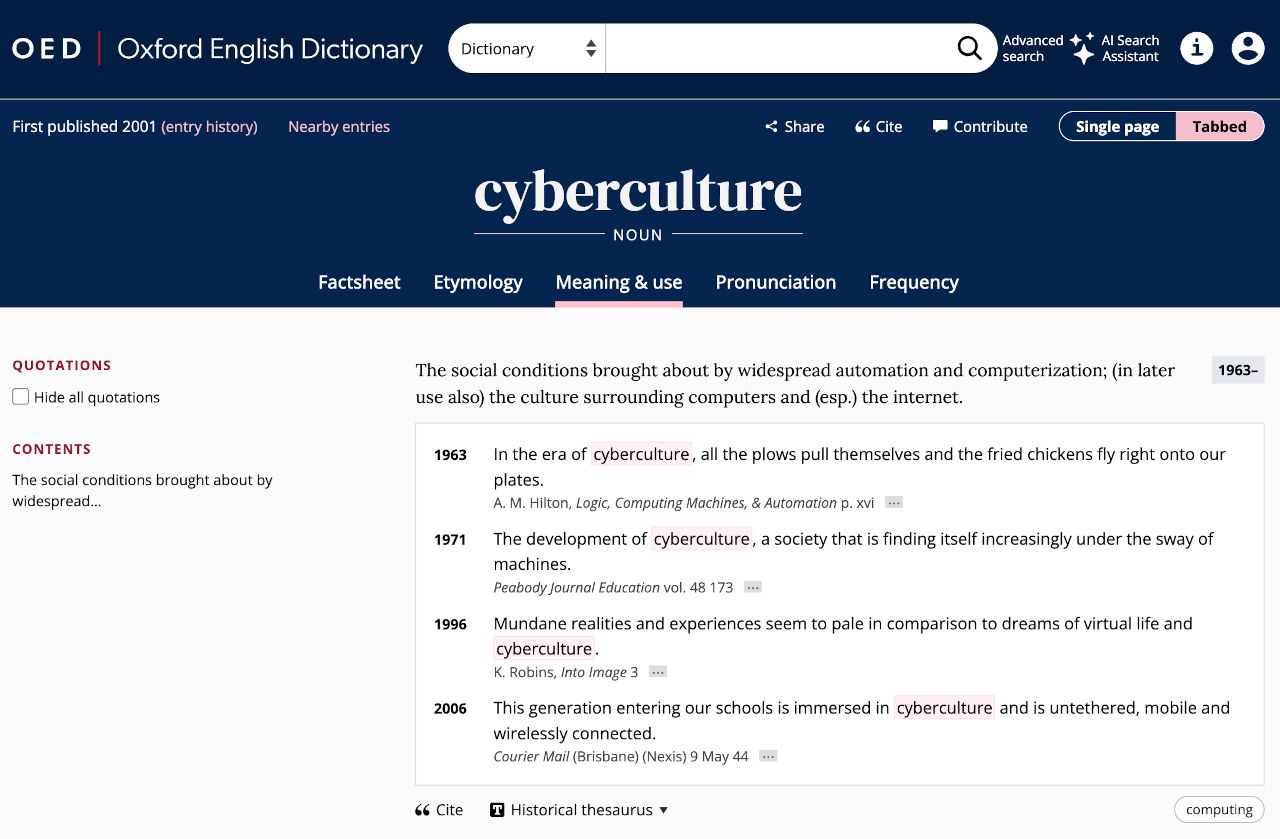

On the other hand, some of what Hilton wrote has aged poorly. For example, this from the book's forward: “In the era of cyberculture, all the plows pull themselves and the fried chickens fly right onto our plates.” Unfortunately, that’s the Hilton quote the Oxford English Dictionary chose to use in its entry for the word “cyberculture.”

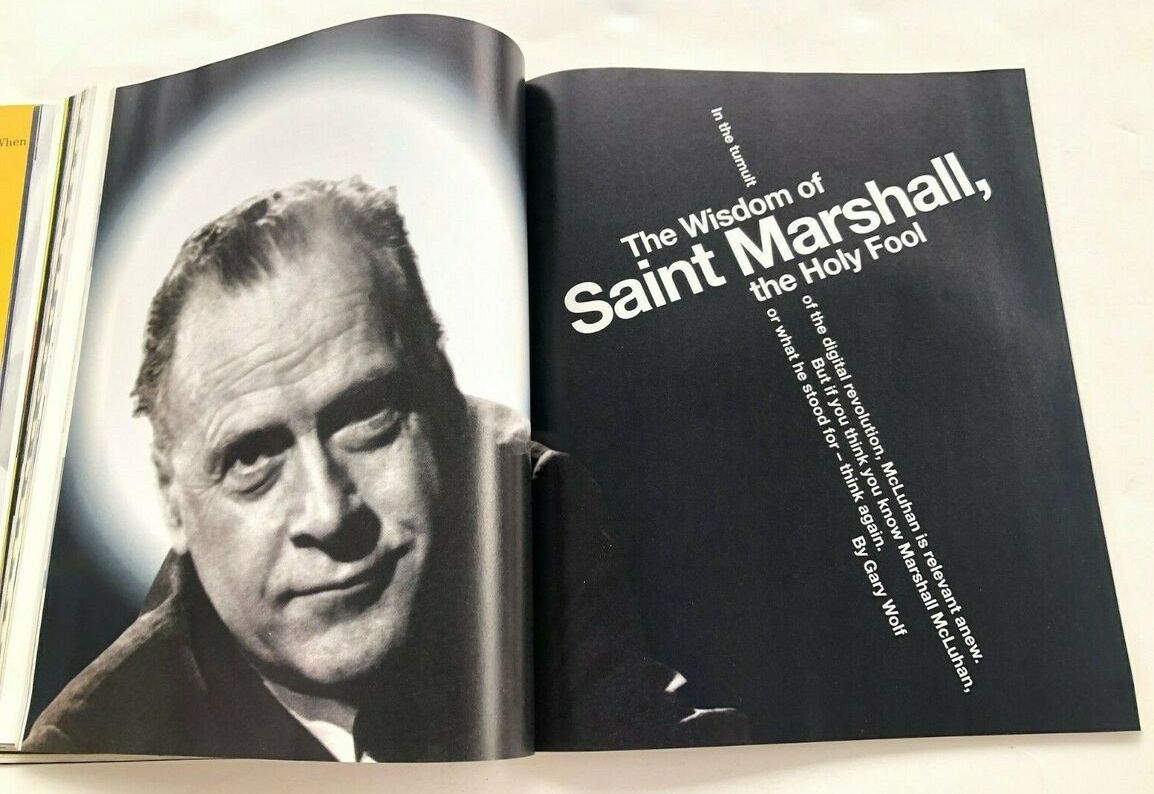

Today, Hilton is almost completely unknown — especially compared to her tech philosopher contemporary, Marshall McLuhan. In his 1964 book Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, McLuhan coined the term “global village.” Like cyberculture, McLuhan's term was often evoked during the dot-com era of the Internet. By then he was long gone — he died in 1980, aged 69 — but he'd ascended into a kind of Silicon Valley sainthood. No really, he was listed in Wired's masthead as its “patron saint"!

In an online excerpt from his 2022 book, Digital Communion: Marshall McLuhan’s Spiritual Vision, Nick Ripatriazone outlined all the other ways Wired (and Silicon Valley in general) worshipped McLuhan:

“Over the years, articles like “Honoring Wired’s Patron Saint,” “McLuhan Lives,” “Five Views of St. Marshall,” and “The Wisdom of Saint Marshall, the Holy Fool” reminded readers of their guiding visionary.”

McLuhan's theories were so popular because they were focused on electronic media and its rapid evolution — a core topic of not only Wired, but many tech magazines and websites during the '90s. Alice Mary Hilton was more concerned about how computers might help human society evolve. While that was a very worthy goal, it was more difficult for ordinary people to get their heads around.

Cybernated Slaves

Hilton held a conference in 1964, the proceedings of which were turned into an academic book published in 1966, entitled The Evolving Society: The Proceedings of the First Annual Conference on the Cybercultural Revolution – Cybernetics and Automation. Flipping through the book, it's clear that Hilton is mainly concerned with the social impact of computerized automation. She has an optimistic view of technology — and in particular, the kind of automation we now associate with generative AI (but which was far more abstract in the 1960s). In this way she's similar to Doug Engelbart, who also believed that computers could lift humankind up.

With Hilton, there's a deep moral and ethical concern too. In her opening essay, "The Bases for Cyberculture," She emphasizes that humans must take responsibility for what the machines do:

"...in the age of cyberculture the theme of human mastery over an obedient, tireless, and completely literal slave is realized. And with such power, human beings bear the heavy responsibility of power."

The word "slave" is applied to computers by others in the conference too. It's a somewhat dubious metaphor now, but Hilton's point is that these "machine slaves" can emancipate us and allow human society to flourish. The following passage from The Evolving Society has since become eerily resonant, with the rise of AI technology in the 2020s:

"We must know how to control our machine slaves not because they are error-prone, but because they are so perfect. Like the genic from the bottle, the monkey's paw, the sorcerer's brooms, and all the other nightmares human beings have always feared in their tales of perfectly obedient slaves, the machines of this new age that can emancipate us and allow us to lead truly human lives, frighten those who are afraid of their own weakness and incompetence. To those who have no faith in man, the machines seem threatening to destroy mankind. But machines cannot destroy mankind; only we, our present generation of humanity, can destroy our own and future generations if we do not learn to be wise as well as omnipotent masters who can use cybernated slaves intelligently and for the good of mankind. Machines are amoral. And what man has created for the benefit of man, he can use also for man's destruction."

Hilton's Institute for Cybercultural Research, formed after the 1964 conference, continued her quest to establish guidelines for a machine automated society. But the institute seems to have petered out by the end of the 1960s. Perhaps she was just too ahead of her time, or maybe she became disillusioned with the rise of personal computer technology in the 70s and 80s — which had more to do with personal productivity than societal improvement. If it was the latter, she followed a similar path to Engelbart, whose vision for an augmented society was also usurped by the more selfish PC revolution.

Cyberculture in the 1990s

Although the Cybercultural Institute didn't last the distance, the word that Hilton coined did — albeit with a meaning that evolved with the times. Basically, it became a buzzword for digital culture.

By the 1990s, there were even specialist “cyberculture magazines.” One of them, Mondo 2000, used the word in its first ever issue back in 1989. In the introduction, co-editors Queen Mu and R. U. Siruis wrote that their goal was “bringing cyberculture to the people!” By which they meant bringing you “the latest in human/technological interactive mutational forms as they happen” (whatever that means). Axcess Magazine was another, with “Music · Cyberculture · Style” sometimes splashed across its cover.

The Mondo 2000 and Axcess sense of the word comes mostly from the cyberpunk authors. William Gibson is credited with coining “cyberspace” in the early 1980s and was one of the pioneers of the cyberpunk sub-genre of sci-fi, along with the likes of Bruce Sterling and Vernor Vinge. Here’s Gibson describing the protagonist of his 1984 novel, Neuromancer:

“He’d operated on an almost permanent adrenaline high, a byproduct of youth and proficiency, jacked into a custom cyberspace deck that projected his disembodied consciousness into the consensual hallucination that was the matrix.”

Tech magazines of the ‘90s were greatly influenced by cyberpunk — Sterling was even on the cover of Wired’s first issue, in 1993.

Soon “cyber” was being prefixed to any number of words, which Wired itself called out in its 1996 book, Wired Style: Principles of English Usage in the Digital Age. Editor Constance Hale wrote in the introduction:

“In too much technical writing, however, tech subjects are a swamp rather than a springboard, filled with useless gobbledy-gook. Many words are just plain overused. Among the words of which we are wary (and weary) are those starting with net.-, cyber- and techno-.”

But Wired doth protest too much, which Hale herself acknowledged. “Not that we at Wired always succeed at following our own prescriptions,” she wrote.

Wired was also a part of Silicon Valley’s transition from tech hippiedom in the 1970s into capitalist techno-optimism in the 1990s. Fred Turner chronicled this in his 2006 history book, From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism. Turner defines “cyberculture” in that book as “a world of individuals and organizations linked by networks of computers.”

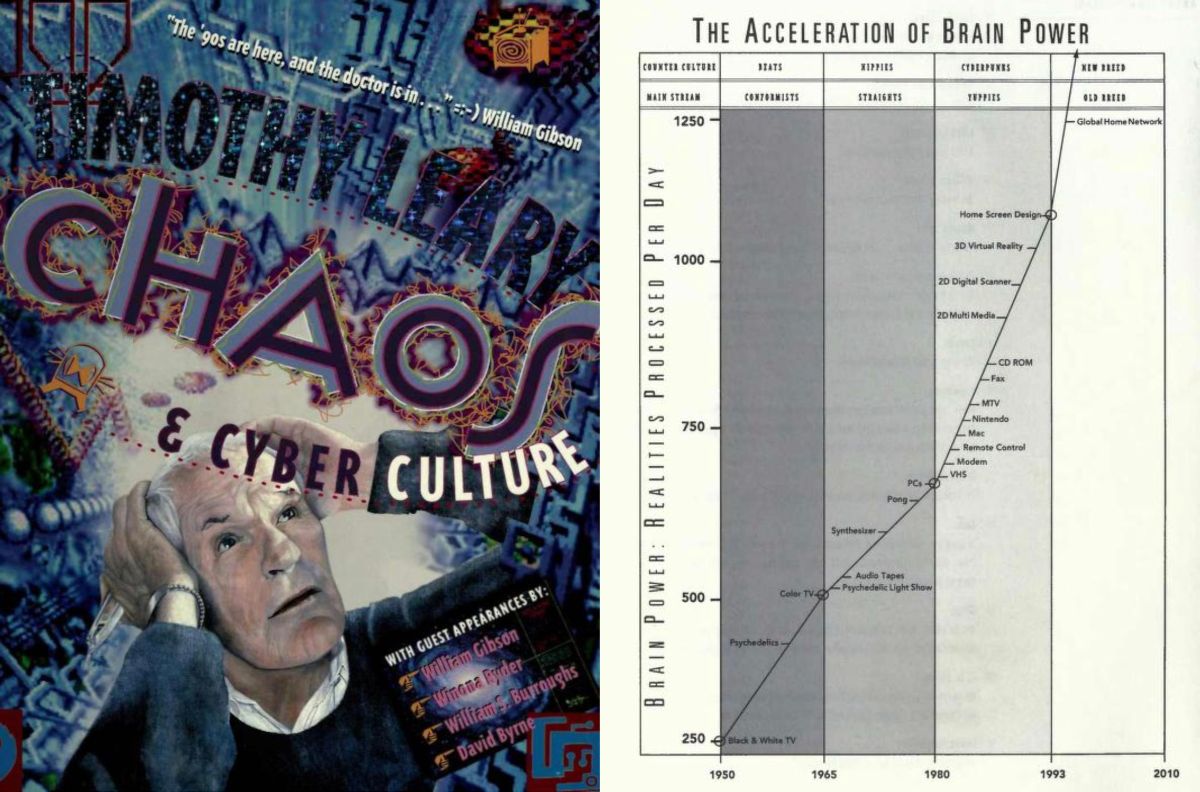

But nothing sums up cyberculture in the '90s better than the final book of Timothy Leary, the 1960s psychedelic drug advocate famous for his catchphrase, "turn on, tune in, drop out." Then 74 years old, Leary entitled his book Chaos & Cyber Culture. It was a sprawling tome, with a lot of quasi-philosophic mumbo jumbo (e.g., the word "quantum" was deployed many times), and featuring conversations with William Gibson, Winona Ryder, William S. Burroughs, and David Byrne. "The PC is the LSD of the 1990s" is one of the blurbs on the back cover (attributed to Time Magazine).

In any case, by the mid-90s cyberculture was an accepted term in the increasingly influential internet culture — for proof, look no further than the cyber-themed Hollywood movies of that year.

Hilton's Legacy

Alice Mary Hilton died in 2011, aged 92. The only media obituary I could find was a paid notice in The New York Times. But there was no mention of her death in Wired; indeed, I can find no reference to her at all in Wired’s web archive. This may be because Hilton changed tack in her career sometime in the 1970s, apparently moving away from technology completely. In April 1981, she wrote a guest article in The New York Times about “the great cathedrals of Europe.” She’s described at the top of the article as “an art historian engaged in research on the mathematical basis of medieval art.”

Hilton could not have guessed then that her word, cyberculture, would be adopted by media academics in the 1990s as the primary descripter of a new type of digital culture — one brought into existence by the Internet. In an essay about cyberculture studies from 1990-2000, David Silver from the University of San Francisco wrote that by the mid 1990s, "cyberculture studies was well underway, focused primarily on virtual communities and online identities." In the second half of the 1990s, he continued, "many academic and popular presses have published dozens of monographs, edited volumes, and anthologies devoted to the growing field of cyberculture."

Nowadays this field of study is more broadly called "media studies." The word "cyberculture" is still kicked around, but usually by people like me who love its nostalgic vibe and associations with the 1990s.

Of course, what Hilton defined as cyberculture — an automated society where mankind is freed from drudgery by computers — is very different to what it ended up meaning in the 90s. You could even argue that McLuhan got it right, that society has been flattened to a “global village" because of the internet. But I for one am more attracted to Hilton's goal (and Engelbart's): to uplift humanity through that same technology. And who knows, Hilton's theories may end up being extremely relevant if AI continues on its current trajectory.

The fact remains that McLuhan got all the glory in internet culture and Hilton was mostly forgotten after the 1960s. Then again, the peak of technology for McLuhan was television (since he died in 1980, before PCs really gained traction). Hilton got to see and experience PCs, then the web and internet culture. Her death in 2011 happened near the end of Web 2.0, so she may even have sampled social media.

Unfortunately, Hilton left no trace of what she thought of the internet and web revolutions. But we can at least be grateful for her 1960s vision for a cybercultural revolution. Some of us are still pursuing it.

I was only vaguely aware of Hilton’s use of the term “cybercultural” when I named my website. When I started this site in 2019 as a Substack newsletter, I was specifically focused on the intersection of internet technology with the ‘cultural industries’ — since I thought I could turn that topic into a business newsletter. I was attracted to the word “cybercultural” because it was a portmanteau of “cyber” — in the internet sense described above — and “cultural.” The fact that the dot-com domain was available sealed the deal! Later, when I pivoted to internet history, I decided that the word “cybercultural” still perfectly described my new goal (to chronicle internet history and its cultural impact) and so here we are… ↩︎

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.