Internet Amnesia: Clive James & His Website

In addition to his many books and tv shows, the late writer and cultural critic Clive James considered websites a viable way to preserve cultural content.

The writer and cultural critic Clive James died last November, at the age of 80. I mainly knew of James from his 1980s and 1990s tv shows, such as Clive James on Television and Saturday Night Clive. I’d also read some of his essays and books before. He was one of those humorous and wise critics – not just about television, but of culture in general – that I always took notice of whenever he popped up in the media or on tv (which was often, at least where I live).

After he died, I was reminded that I hadn’t read as much of his work as I should’ve. Particularly as James was as penetrating a cultural observer as we’ve ever had. So over Christmas I read perhaps his most important work, certainly from a cultural point of view, the 850-page doorstop of a book, Cultural Amnesia. It’s an eclectic history of culture in the twentieth century and does a surprisingly good job of summarizing such a complex and chaotic period in our history.

Given its grand sweep, the book can’t help but dip – more often than is comfortable – into the dismal aspects of last century. So the atrocities committed by Hitler, Stalin and Mao are often examined. Yet within all that horror, James managed to unearth a persistent streak of wondrous humanism that ran through the twentieth century, principally via its cultural content.

What I hadn’t realised until I read Cultural Amnesia is that James considered websites a viable way to preserve cultural content too. That the very humanism he espoused and illustrated throughout the book was also available, in hyperlinked form, on his own website.

He saw his website as a way to preserve his work, and even in a sense live forever. He told The Financial Times in 2015:

“The website is a version of immortality, isn’t it? It’s a bit like an Egyptian pyramid without the drawbacks. It doesn’t take up any space. When I caught myself thinking of living for ever through the website, I, luckily, was saved by a more sane and humane insight, which is to preserve other people’s stuff, along with mine.”

James often “got it right,” as the title of a loving obituary in The New Yorker put it. The writer of that piece, Adam Gopnik, knew James in person (he tells of being with him during one of his late medical emergencies, and supplying him with books in the hospital). Gopnik wrote about James that “appetite was his great engine, but appraisal was his greatest gift.”

I have no doubt that’s true about James’ essays and thoughts about literature and culture, but unfortunately he didn’t get the Web right. At least not the Web as we now know it. Because far from preserving our culture, the Web is at best forgetting it and at worst erasing it. As it turns out, a website is much more vulnerable than an Egyptian pyramid.

The internet theorist Doc Searls wrote in a recent essay:

“Today the World Wide Web, which began as a kind of growing archive—a public set of published goods we could browse as if it were a library—is being lost. Forgotten. That’s because search engines are increasingly biased to index and find pages from the present and recent past, and by following the tracks of monitored browsers. It’s forgetting what’s old. Archival goods are starting to disappear, like snow on the water. Why? Ask the algorithm.”

We can certainly blame the algorithms of Big Tech for burying the past, but we must also apportion some of the blame on the software used to build websites – often developed by those same corporations. Previously trendy but now defunct Web technologies like Flash and Shockwave have made many websites from the 1990s and early 2000s inaccessible now – even on the Internet Archive, which is otherwise a global treasure of online culture from our recent history.

The Internet Archive operates a time travel search engine known as The Wayback Machine, and it’s increasingly the only method of accessing past websites that have otherwise disappeared into the ether. Many old websites are now either 404 errors, or the domains have been snapped up by spammers searching for Google juice.

I’m currently writing a nonfiction book whose setting includes the Web of the 1990s and early 2000s, so I’ve been frequenting The Wayback Machine a lot this year. Alas, many of the websites I try to view in Wayback are beset with HTTP errors, redirect loops, or are no longer accessible due to obsolete technology.

Even if a website was built using just that most basic of World Wide Web code, HTML, it may still have died off due to a missed domain name renewal or a web host that went under.

Of course, Clive James had the noblest of intentions when he started his website (as many of us do). He aimed to “offer a critical guide, through the next medium, to works of thought and art.” Those words still grace his homepage today.

A browse through the content of his website is a satisfying – and edifying – way to spend an hour on the internet. The menu is neatly categorized by content type (Books, Essays, Poetry, Lyrics, Video, Radio). Each section features a selective list of James’ works.

In the Books section is a list of all his books, helpfully put into sub-categories (Memoirs, Cultural Commentary, etc.). Some of the books listed have their own web page, but not all of them. The page for the book Cultural Amnesia has an introduction composed specifically for the website. There’s also a “cast list,” a “buy this book” link, a link to extracts published on Slate, and a list of linked reviews.

James’ website is a little treasure trove of his life’s work, and it’s holding up well in 2020 – although the design is a bit outdated and the site is slower than average. While the content is not a comprehensive overview of his career, it’s fair to say that had ill health not intervened then he would’ve made more progress preserving his own – and others’ – cultural content. His home page states:

“After a large-scale rebuild in late 2009 to rationalise the structure, the site was all set for some heavy loading, but annoyingly I fell ill in early 2010 and all work except for routine maintenance had to slow right down.”

That homepage message is dated June 2013, at which point he says he is “getting up to speed again” on site maintenance. Even though James lived another six years and change, it’s unclear if he updated the site again after 2013.

He does note that the website is only operational at all thanks to his webmaster Dawn Mancer, “who understands how the machines work.”

As far as I can tell via LinkedIn, Dawn Mancer is a self-employed webmaster who did freelance work with James. She is still listed as the site manager, in the footer. Probably she added the obituary for James (penned by the man himself) onto his author page.

So the website lives on for now, albeit we don’t know who’s in control (Mancer? James’ estate?). We also don’t know how often – if at all – the site will continue to be updated. Or how long its web hosting agreement runs to, and whether it will be renewed.

But the basics of Clive James’ online presence are all in place, so there’s no immediate reason to fear that the website will pass away.

The domain, clivejames.com, was registered in June 2003 and has been reserved until June 2022 (it was last renewed in August 2019, a few months before James’ death). It seems James or his people originally acquired the domain from someone else, since an August 2000 BBC report quotes James as saying the domain had “already been snapped up by another Clive James – he’s a jetski instructor in Miami.”

Incidentally, the same BBC report noted that “in the long run he hopes to start using the internet as a medium for getting his writing and broadcasting to a new audience.”

In February 2009, clivejames.com was set up on the website builder and host Weebly, a Web 2.0 equivalent of previous Dot Com site building services like Geocities and Angelfire. In April 2018, the payments company Square, Inc. acquired Weebly, suggesting its future will revolve around the building and hosting of e-commerce websites. I mention this only because it’s possible that in a few years Weebly will no longer be an appropriate web host for clivejames.com, unless it sets up an online store to sell James’ books and DVDs.

If Weebly does indeed, as they say in the business, ‘pivot’ away from basic websites, will anyone in James’ estate be motivated to move web hosts? That will almost certainly require a re-design, so it won’t be a straight forward process.

Again, I’m not saying Weebly will abandon personal websites. I sincerely hope it doesn’t. But one thing I’ve learned as a long-time internet commentator is that jarring change to existing customers is always a possibility whenever a startup gets acquired.

Take Weebly’s direct ancestor, Geocities. It was founded in the mid-90s and soon became extremely popular, which enticed Yahoo! to acquire it for $3.57 billion in January 1999. But in the 2000s, Geocities was quickly usurped by blogging tools like Blogger and WordPress. Ten years later, Yahoo! closed down Geocities. The sites could still be visited up till 2014, but after that they were erased forever. As Wikipedia put it:

“Many of the pages formerly hosted by GeoCities remained accessible, but could not be updated, until 2014. Attempts to access any page using the original GeoCities URL were forwarded to Yahoo! Small Business, but now generate a Yahoo! HTTP 404 error.”

Today, the only way to access websites built on Geocities is to visit The Wayback Machine; and that’s only the case because the Internet Archive ran a specific project to preserve Geocities. What if Weebly is eventually shuttered by Square, but the Internet Archive decides it does not have the resources to save it?

The Web changes fast and history has shown it’s not always kind to the recent past.

Clive James was one of the great preservers, and explainers, of twentieth century culture. Even up to 2016, with his book about streaming tv entitled Play All: A Bingewatcher’s Notebook, James was a master of appraising cultural content. There’s no doubt his books – and even some of his television work – will live on in our culture. I for one will continue reading and watching his work.

I wish I could say the same about clivejames.com living forever, but I fear it will be gone before long. That’s no fault of James himself, who tried his very best – even in ill health, near the end – to preserve his own and other people’s work on his website.

No, it’s an indictment of internet corporate culture that websites like clivejames.com are more likely to die off, than live on.

Update, 1 March 2020

After this article was published, I was given a tip on Twitter to contact Stephen J Birkill, who runs a website devoted to Clive James’s songwriting partner Pete Atkin (peteatkin.com). I emailed Birkill, who informed me that in fact clivejames.com did go offline at the end of 2018, when its hosting service wasn’t renewed. In August 2019, with the official site still offline, Birkill decided to create his own online archive of James’ work using The Wayback Machine copy of clivejames.com as foundation. As a temporary measure, he put the WIP archive on his peteatkin.com server.

While he was working on the alternative archive, in September 2019 the official clivejames.com site suddenly re-emerged – thanks to its webmaster Dawn Mancer (who I mentioned in the essay). According to Birkill, it had “a whole new, modern, WordPress-y look.”

At this point, just a couple of months before James would pass away, Birkill was invited to visit James’ home. Birkill told me via email:

At the invitation of Clive’s daughter Claerwen and in the company of Pete Atkin, I visited Clive at his Cambridge home in October, just seven weeks before his death, and we agreed that I continue to construct the archive, in parallel with and quite independently of Dawn’s site, and that Claerwen would take over from Dawn the editing of the ‘official’ clivejames.com. In that way we could together work towards the preservation of his legacy, an end we all strongly believed in.

The end result is that there are now two Clive James websites: the official one, clivejames.com, still run (at time of writing) by Dawn Mancer on Weebly; and a second one being built by Stephen Birkill, currently residing in draft form at clivejames.peteatkin.com. You can read more about Birkill’s project here.

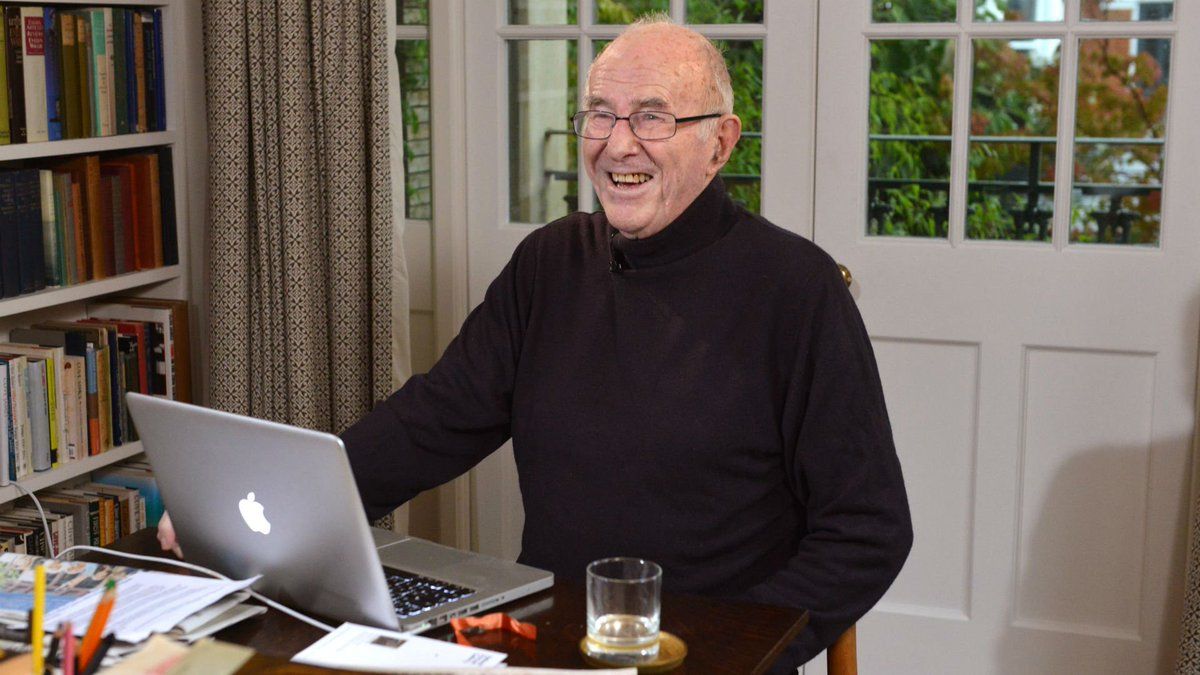

Image credit: BBC Radio 4 Today

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.