BowieNet: The Inside Story of its Creation

Part web portal, part ISP, part proto-blog, when David Bowie and his web team launched BowieNet in 1998, it was truly revolutionary. Cybercultural interviews one of its creators.

In late 1996, just before his 50th birthday concert at Madison Square Garden and before his latest album ‘Earthling’ was released, David Bowie had quietly approved the development of what was to become his biggest internet legacy: BowieNet. It was to be more than Bowie’s official website; it would also do business as an Internet Service Provider (ISP), meaning it would provide internet access and an email address to users. Most importantly, it would be an officially endorsed online community for his fans.

BowieNet was the brainchild of Bowie insider Robert Goodale and a multimedia producer named Ron Roy.

Goodale, a New York City entertainment attorney, was running Bowie’s business management company Isolar at the time. It was a role he’d obtained through his close relationships to Bowie and his main financial partner, Bob Zysblat. In addition to Isolar, Goodale had become Bowie’s go-to business contact for anything to do with technology and the internet — he was listed as executive producer on the ‘JUMP’ cd-rom in 1994 and Bowie’s original website in 1996.

Goodale and Roy first met in the summer of 1996, Roy told me in an interview in March 2020. When he met him, Goodale was winding down his time at Isolar. He was looking for opportunities in the internet space and “wanted to continue to do really cool innovative things,” said Roy.

In the summer of 1996, as Goodale was preparing for the release of the ‘Telling Lies’ single — which Bowie would be releasing as an exclusive online download on his website — he reached out to Roy to discuss working with him.

“I was a partner in a technology company in Connecticut,” Roy explained, “and one of our specialties was hosting. We built the ISPs, we built some community based things for ISPs. But really we hosted software companies, real estate companies and some e-commerce companies. So through this, Bob heard about me and he reached out to the company. He actually came out to Connecticut.”

The object of the meeting was to discuss Roy’s company providing backup services for the ‘Telling Lies’ online release. Goodale’s biggest concern about the project was ensuring that the bandwidth and hosting held up. Roy was thrilled about the prospect of working in some capacity with David Bowie; he was a music buff and had been a Bowie fan from the early days.

In the end, ‘Telling Lies’ was released without Roy’s involvement, in September 1996. While naturally disappointed, Roy had made a valuable contact in Goodale. The pair kept communicating.

How BowieNet Originated

As Roy tells it, BowieNet originated from he and Goodale spitballing ideas.

“He [Goodale] said, let's figure out something to take David that will knock his socks off, and he hasn't heard before. The place we landed on was doing a private label ISP.”

The pair thought there was an opportunity to offer something different than the dominant consumer ISPs of the era — companies like AOL, CompuServe and Prodigy in the US.

“We came up with this idea of, what if we could take the backend technology of how those ISPs work and create something that became BowieNet. What if we could use the leverage of David Bowie and create more of a fun, more media-centric, music-centric, art-centric community. And that's really where we separated ourselves, because instead of trying to be really big — all things for all people — we went in the opposite direction. We wanted to create this really tight community of passionate music people.”

David Bowie, the pair agreed, was “the perfect launching pad to do this.”

In retrospect, it was the community aspect and fan interaction that was to prove key to the success of BowieNet over the coming years. Those parts of BowieNet made it into a truly innovative social network, years before MySpace and Facebook arrived on the scene. But it was the ISP foundation that paved the way for all this. At the time, millions of people had yet to sign up to an internet provider, so helping “on-ramp” Bowie fans to the internet was a viable customer acquisition strategy.

Some further context: during this era, the leading American ISP, AOL, was struggling to meet demand from consumers. That opened up opportunities for smaller companies. Indeed, any company — no matter how small — could make a deal with a telco or one of the many infrastructure companies that leased dial-up capacity (remember, this was before broadband). So access wasn’t an issue. It was also relatively easy to compete with AOL on price. Full access to BowieNet, including unlimited internet access, was eventually priced at $19.95 per month. This compared favourably to AOL’s pricing at the same time, which was $21.95 per month for unlimited access.

Where the likes of AOL and Microsoft had a distinct advantage was in name recognition and a wider array of content and services on their web portals. But again, when it came to name recognition, David Bowie was a good ‘brand’ for Goodale and Roy to hang their ISP hat on. And Bowie certainly took care of the content side of their pitch to consumers — exclusive Bowie content would be manna from heaven for many of his fans.

Goodale and Roy were convinced they were onto a good thing.

Pitching Bowie

The ultimate plan for BowieNet was not just to create an ISP service plus online fan community for David Bowie, but to also offer the platform to other artists and entertainers. Any celebrity or sports team with a large fan following could get in on this, thought Goodale and Roy.

But Bowie would be first, and that would be a key part of their pitch to him. Bowie had always wanted to be seen as an innovator, not just in music but in everything, so being the first to launch a new type of product on the internet would likely be a big driver in his decision-making.

Roy traveled to New York City in the fall of 1996, for a meeting between he, Goodale, and Bowie’s manager Bill Zysblat.

“We spent a couple hours with Bill, pitched the concept, and Bill liked it a lot.”

However, Zysblat wasn’t convinced Goodale and Roy could pull it off. “There's a lot of missing parts to this,” he told the pair. Not the least of which was the lack of a technology partner for the ISP. Nevertheless, Zysblat promised to “get in front of David” and share the idea.

“It was about a week and a half later,” Roy recalled, “and Bob called me and said, get your ticket because you're coming into the city again. David wants to meet with us.”

It was a dream come true for Ron Roy, who had followed Bowie’s career since the first time the singer had traveled to the US, in 1971. Now here he was, an unknown internet guy from Connecticut with a not yet fully formed ‘dot com’ idea, about to pitch one of his heroes. The meeting was to be held at Zysblat’s company headquarters in New York City.

“Bill’s company was called RZO, and I was in this very nice conference room and two doors opened up,” Roy told me, his voice tinged with excitement recalling the moment. “And there's this guy right in the middle of the opened doors. He had this long trench coat on, and these camel-coloured boots. And there's Bowie!”

The pitch session lasted about 90 minutes, double the time Zysblat had scheduled. Bowie had a lot of questions, he was engaged, and he went out of his way to make a nervous Ron Roy feel comfortable.

Right away, Roy could tell that Bowie liked the idea. But then again, he understood that Bowie must get pitched with a lot of different business propositions. He and Goodale hadn’t even worked out the technical arrangements for this concept, and yet they were expecting Bowie to attach his name and considerable reputation to it? For someone of Bowie’s stature, it was a big risk. They had better be able to pull this off!

After the meeting, Roy didn’t know whether he’d ever see or talk to Bowie again.

Fortunately, Bowie gave the go-ahead towards the end of 1996. Even better, he also wanted to invest in Goodale and Roy’s plan to make it into a business for other artists and entertainers.

The Backend Deal

Zysblat warned Goodale and Roy that the first thing they needed to do was sign up a technology company to run the ISP. But he gave them permission to use Bowie’s name during this process. As Roy recalled, they’d be able to tell potential partners that “David Bowie is going to be the first private label music ISP in the history of the Internet.”

“So then everything fell on me,” laughed Roy, “because that was more my background than Bob's. So I just started calling around. I knew AOL very well. Prodigy was twelve miles from my house, so I visited them.”

But the big consumer ISP companies didn’t bite. Roy started reaching out to more business focused ISPs and finally found a match with a Californian company called Concentric Network Corporation.

“I literally cold called them,” Roy said. “I’d read about them, they had raised a lot of money, and had an amazing management team. I also liked that Concentric had a lot of big clients — banking and hospitals. So I knew they had a really solid infrastructure.”

Even so, it took four or five months of negotiations and planning before the Concentric deal was finalised. Concentric would provide the infrastructure to run a Bowie-themed ISP, as well as e-commerce capabilities.

As Roy put it, Concentric would “be our backend service provider, help us brand everything, do all the [customer] transactions, mail out the [dial-up connection] CDs, and do everything you needed to do at that time to create an ISP.”

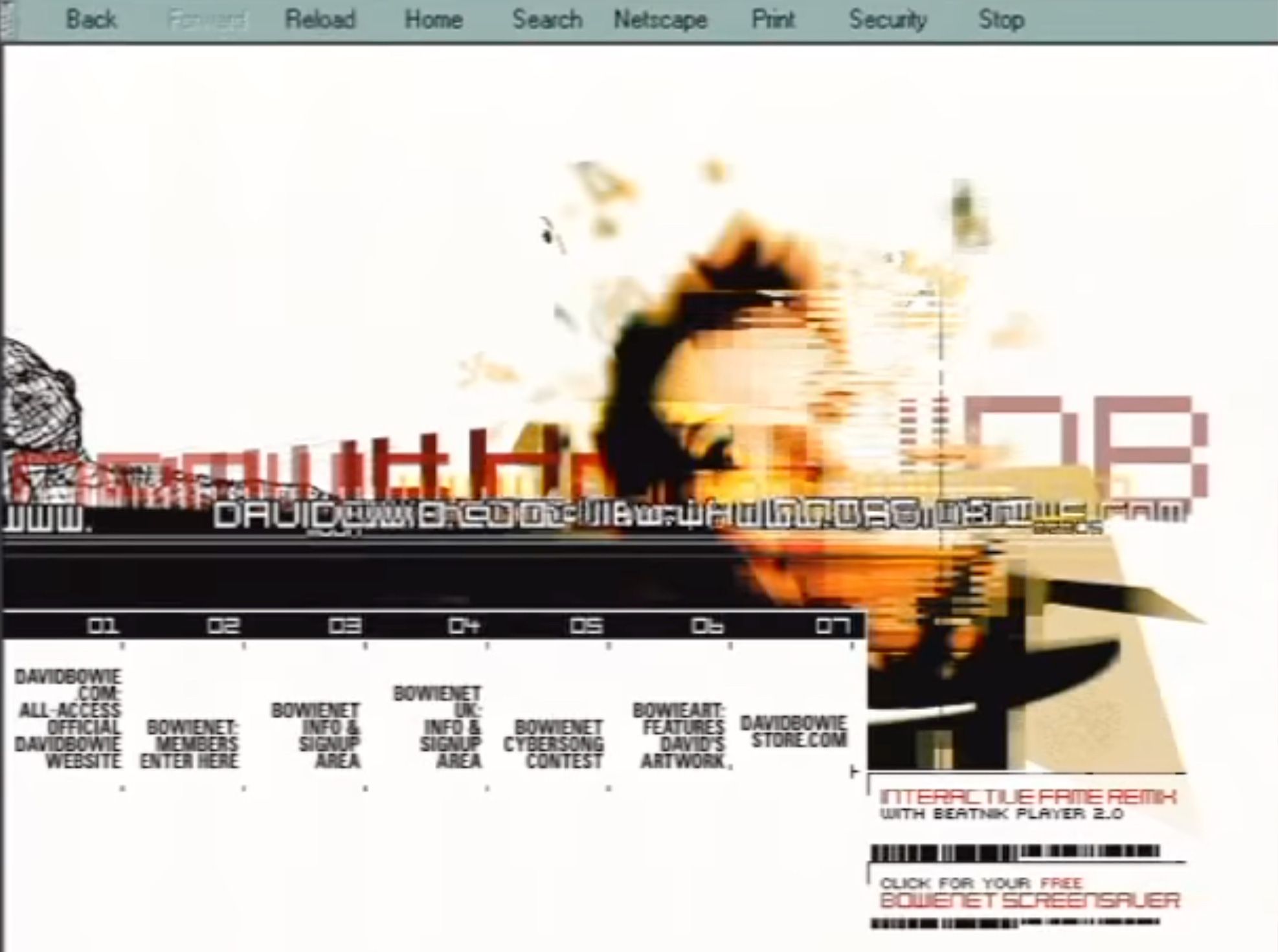

Bowie’s Web Design

Bowie had also told Goodale and Roy that he wanted to find a hotshot web design firm of his own. Up till then, he’d relied on his record label to manage his website. Even though it had undergone multiple re-designs up till that point, and the latest ‘Earthling’-themed iteration designed by a company called N2K was well executed, Bowie wanted to take control of the process. He asked Goodale and Roy to find him a design firm that would take his vision of how he wanted to represent himself on the Web, and make it a reality.

“Bob and I met with so many different people and a bunch of different firms. We landed on a company out of Canada which had an office in New York City, called Nettwerk. They were really into Flash early on, really did a lot of innovative things.”

Nettwerk was a Vancouver-based indie record label which, after making a name for itself producing “enhanced CDs” for artists, created a spin-off web design company called Nettmedia. Specialising in creating multimedia websites for musicians, the company soon became a regular feature in Billboard’s awkwardly-named ‘The Enter*Active File’ news section.

Reportedly, Bowie was particularly impressed by Nettmedia’s work for Lilith Fair, a festival featuring female rock and folk musicians. In any case, it became Bowie’s web design firm from 1997 on.

As you’d expect of a visual design and fashion icon like Bowie, he had ideas about what he wanted BowieNet to look like.

“In the beginning, he wanted something dark,” Ron Roy told me. “He also wanted a design that was unique, that you just didn't see anywhere else.”

The Development Process

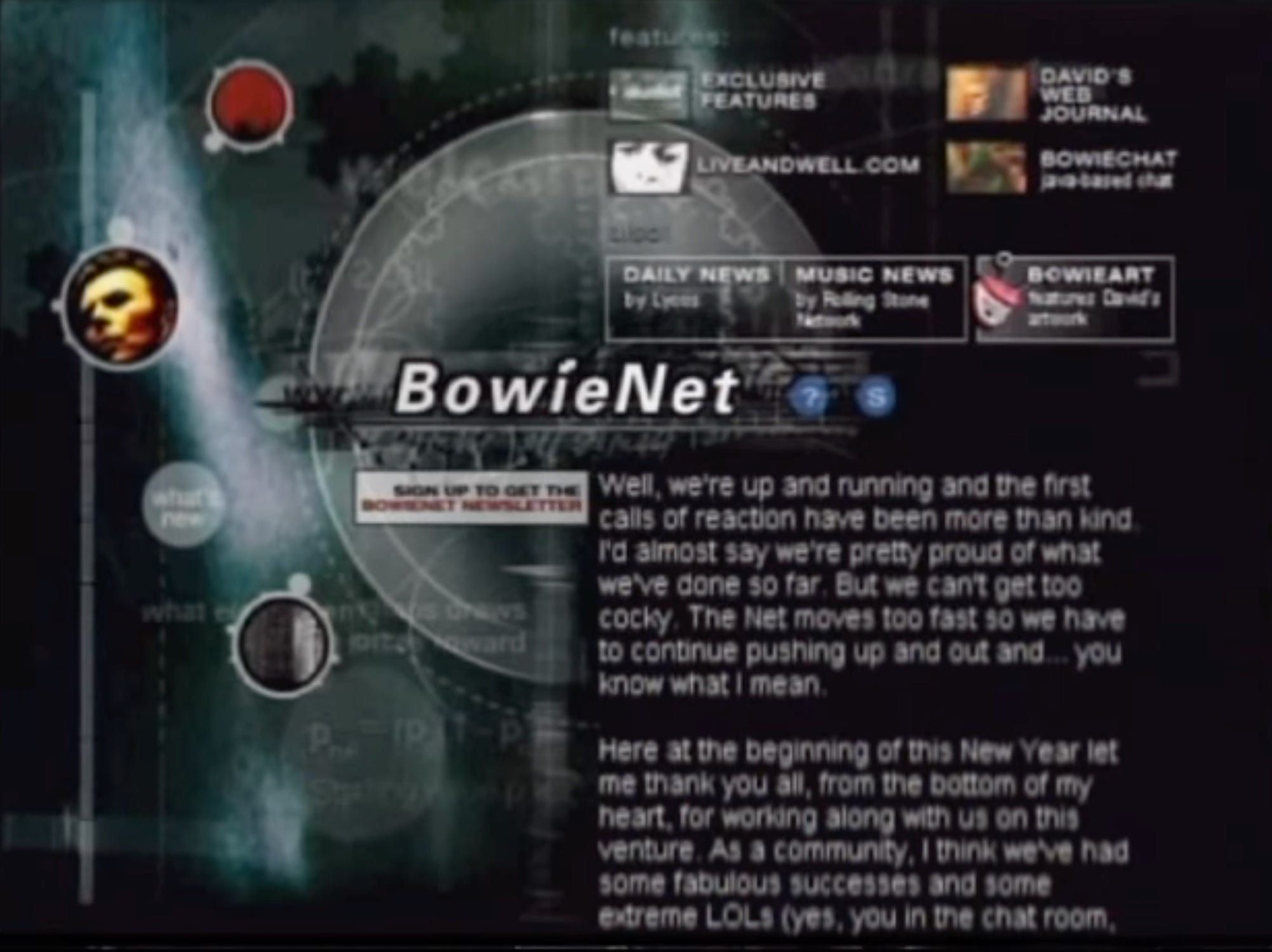

Bowie was involved in the early planning for the website, along with Roy, Goodale, Nettmedia and others. The focus was always on fostering community among Bowie fans, but a core decision from the beginning was to emphasise creativity on the site. They didn’t want BowieNet to be just another place to chat online.

“So we created all these places in the site,” said Roy, “where people could post their art work or post a poem. Down the road, people could even post little five-to-seven second audio clips.”

Remember this was years before ‘user generated content’ became fashionable on the Web, so at the time Bowie’s focus on making his website a creative space for his fans was unique. He was adamant that BowieNet not become a “brochureware” site, which was a web design term from the 1990s describing a one-dimensional informational website (the equivalent of a paper brochure before the Web).

“The last thing he needed was another electronic billboard of who David Bowie was,” said Roy. “He didn’t want a marketing site to try to sell albums or concert tickets. He wanted this to be an interactive community of people, who could go to the site to contribute and learn…and have fun!”

In the second half of 1997, Bowie was on his worldwide ‘Earthling’ tour, so he had to necessarily take a step back from the website development process. But he kept in regular communication about it.

“He was a power emailer,” chuckled Roy. “Sometimes it was just ‘how's it going’, or we would get him something to look at — you know, log into this site and look at this design, and we’d get his feedback. I mean, you have to understand his name was on this. He was in communication all along the way. Mostly email, or he'd be in communication with Bill [Zysblat, his manager], who was on tour with him. I don't think a week went by that we didn't hear from David, whether it was directly or through Bill.”

Goodale and Roy worked full-time on BowieNet, with the web designers and technical people on retainers. They hired consultants and other freelancers as needed.

“David invested some money, he gave us a runway of about a year,” said Roy. “So we had to be lean and mean too.”

Roy described his and Goodale’s job as “piecing together all the things that eventually became the launch of BowieNet.”

Roy was point man for the backend technology, so he worked closely with the ISP provider Concentric. Being an attorney, Goodale’s speciality was doing the business deals and so he handled all the contractual negotiations. Both managed the design phase. Roy told me that, overall, their partnership was a “50/50” relationship.

BowieNet Announcement

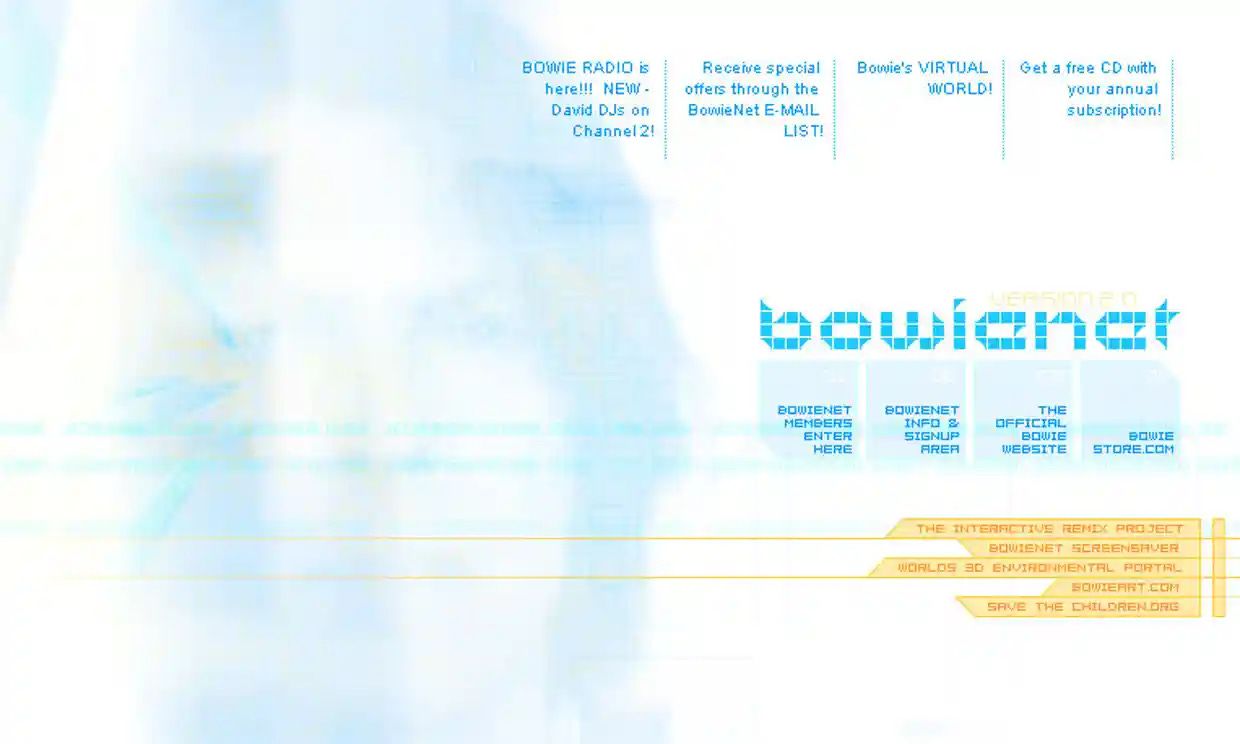

On 17 July, 1998, BowieNet was announced to the world. Rumours had been circulating for a few weeks due to a leak at EMI, so Bowie’s management issued a press release to confirm it.

BowieNet was to launch on 1 September, offering “high-speed Internet service across North America and, by year end, throughout the world,” plus a raft of features including “a fully customizable home page, davidbowie.com e-mail address ([email protected]), news groups, chat rooms, online shareware, multi-player gaming, and much much more.”

As per Robert Goodale and Ron Roy’s original business plan, there would be a good assortment of exclusive content to entice Bowie fans — as well as “music fans in general” — to sign up. Fans were promised “previously unreleased audio tracks, videos and photos,” together with “numerous cybercasts (both live and archived) from Bowie as well as other artists.”

Pricing was reasonable for the time. You could choose to sign up to the full ISP service for $19.95 per month, or remain with your current internet provider and access davidbowie.com for $5.95 per month.

Bowie’s comments in the announcement were typically ambitious, stating that he didn’t just want to attract his own fans — but “all music lovers.” He wanted BowieNet to be “a single place where the vast archives of music information could be accessed, views stated and ideas exchanged.”

He admitted that obtaining “unique proprietary content” to sit alongside his own exclusive Bowie content would be challenging. He also recognised that the technical platform for internet access, “from tech support to billing,” needed to be top notch. But, he said, “after nine months of work, I believe we have achieved just that."

The announcement of BowieNet also doubled as the coming out of Goodale and Roy’s new company, UltraStar. It was billed as “a management technology partnership that specializes in the arena of Internet services, bringing major entertainment, sports and fashion clients to the world in a community-based forum delivered over the Web.” Bowie’s manager, Bill Zysblat, was listed as a Principal of the company.

Goodale and Roy spent a lot of their time in the months leading up to the launch making partnerships for BowieNet and marketing it. Not only did social media not exist at the time, but even Google had yet to incorporate (that would happen on 4 September, just a few days after BowieNet’s launch). So Goodale and Roy had to utilise offline media like magazines and newspapers for marketing, as well as tap into the audiences of the big internet portals. Bowie himself was more than willing to help.

“David was great,” Roy told me, “because he would agree to do a chat on AOL or Yahoo if he could promote BowieNet. He was willing to get out there and help carry the flag. As you know, when you launch something it's all about awareness.”

As launch day approached, BowieNet was looking good. But not all of the desired features made it to the final product.

“We wanted to do more video streaming,” said Roy, “but bandwidth was just 56 kbit/s back then. And you only have one launch party, so didn't want any mistakes.”

Bowie’s Blog

A week before BowieNet launched, Bowie started an online journal. Initially posted to his existing website, the intention was clearly for it to be a regular feature on BowieNet. The first entry, dated Sunday August 23rd, 1998, began:

“I should suppose that an interesting and nicely arbitrary way of starting these journals is to make a few notes on various stories and rumours that have been floating around on the Net, write a little on what day-to-day life seems to hold, and maybe go back a few years, try to catch a glimpse of all that.”

However, the initial entries are less an intimate look into the mind of a great artist, than Bowie blandly talking about Hurricane Bonnie and making tepid surrealistic jokes. He also dutifully promotes the upcoming launch of BowieNet (“I boot-up and go on-line and watch the countdown clock on Bowienet.”).

Where the journal is most effective is when Bowie uses it to muse on his song writing process. Here he starts to sound more genuine.

“Tried some new song ideas this morning. I'd been listening to the sweet sound of the Semar Pegulingan, regularly called the gamelan or Balinese orchestra. It never fails to transport me to another place and way of thinking.”

He is careful to reference a couple of his fan sites in the journal, in a fairly obvious attempt to curry their favour before the launch of BowieNet. Paul Kinder’s Bowie Wonderworld site gets a shout-out (“I found the Bowie diaries on Little Wonderworld and, boy did they take me back.”) and Evan Torrie’s Teenage Wildlife is also referenced (“Talking of fog, yes, Teenage Wildlife. I did just do a track of the old Gershwin song 'A Foggy Day in London Town’.”).

The Friday before the big launch, Bowie obliquely talks about the last minute preparations:

“Boy, is the work on-line getting serious or what. Nettmedia is going crazy trying to up-load everything on time. There are still major plumbing problems in some areas but everything should look halfway decent when we go on Monday night.”

On Sunday, he’s nervously anticipating the next day:

“This is supposed to be the day of rest but as soon as we get back from our walk Iman goes to make coffee and I tunnel my way into the computer room, checking on content for the ISP.”

On the big day, he posts a final message at 5pm a couple of hours before go-live:

“THIS IS IT THEN. I have to submit this journal right now or I'll miss the deadline for tonight”

He thanks his website designers, Nettmedia, “for putting up with my constant fidgeting and last minute changes and additions and moans,” and ends with “...and here we go.”

Image credits: YouTube video of David Bowie interview on ZDTV's Internet Tonight, June 1999.

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.