1997: The Year of DHTML

DHTML, or Dynamic HTML, was essentially a combination of HTML, JavaScript, the newly released CSS standard, and an emerging web programming model called the DOM (Document Object Model).

As we saw in the previous post, 1997 was a year of growth for JavaScript. However, it was also a year in which its limitations were recognized and a new term was coined that both embraced and extended JavaScript. DHTML, or Dynamic HTML, was essentially a combination of HTML, JavaScript, the newly released CSS standard, and an emerging web programming model called the DOM (Document Object Model). That said, the precise definition of DHTML depended on which browser company you spoke to: Netscape or Microsoft.

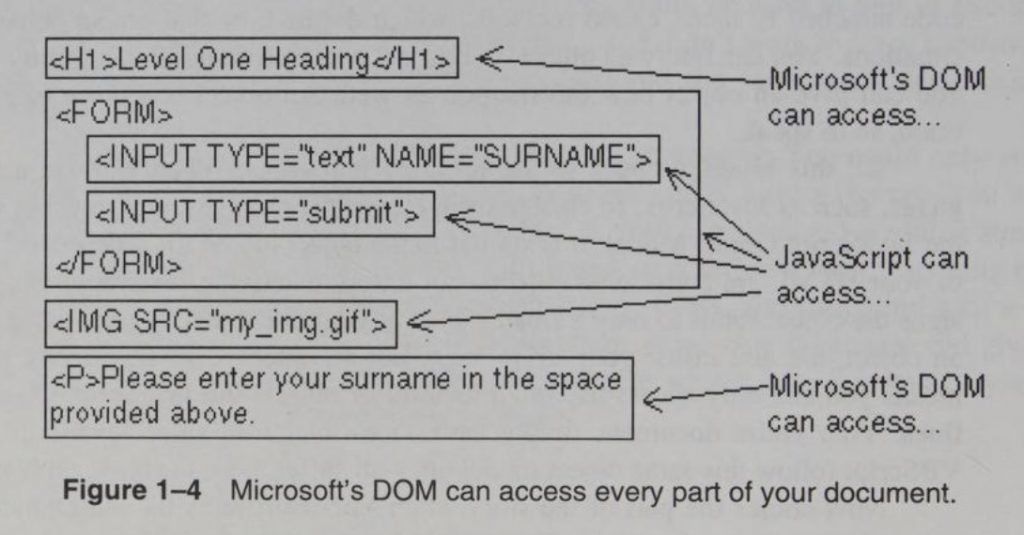

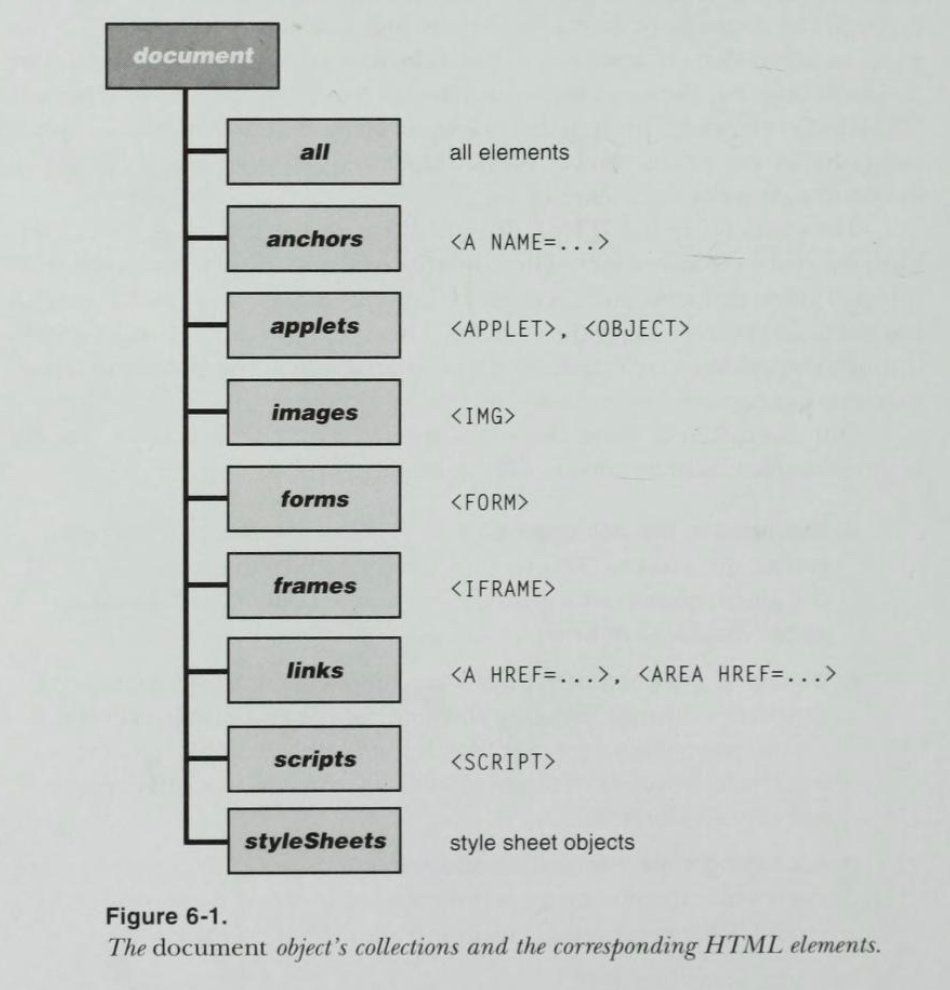

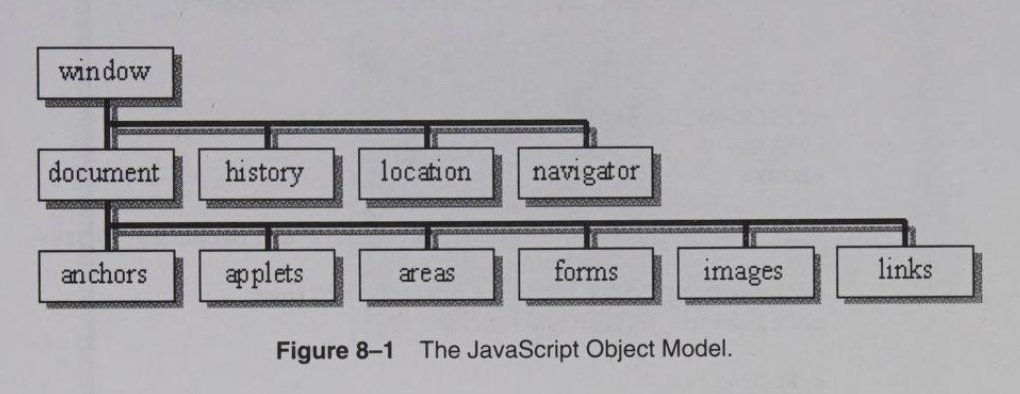

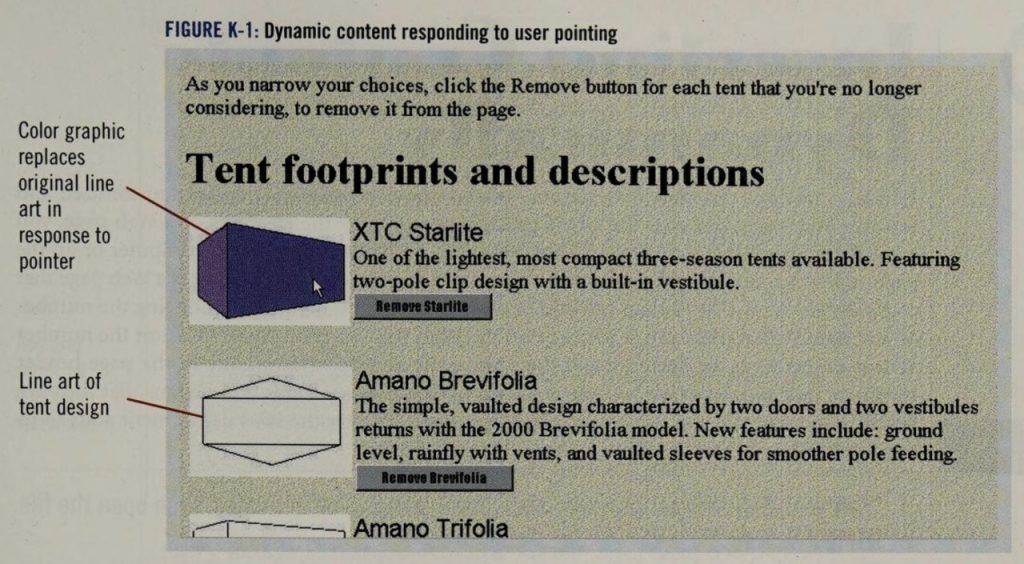

As it turned out, Microsoft’s vision for DHTML was more compelling from a technical perspective than Netscape’s (perhaps the first time that could be said about a web technology Microsoft pioneered — but it would not be the last). What Microsoft wanted to achieve with DHTML was to make every element of an HTML document into a programmable object. JavaScript was, at the time, mostly limited to interactivity of forms and images. Microsoft’s DHTML, though, aimed to expand the canvas for interactivity to the entire web page.

As Robert Mudry put it in his book The DHTML Companion, released at the end of 1997:

“Microsoft saw the JavaScript Object Model and realized that in order for a scripting language, any scripting language, to be truly useful, it must have full access to every piece of your HTML document. Everything must be recognized as an object.”

One of the architects of Microsoft’s version of DHTML was Scott Isaacs, who worked for Microsoft for 20 years (1993-2013). He also authored a 1997 book about DHTML, released a month or two before Mudry’s. In 2005, Isaacs told the Microsoft Channel 9 video team that “DHTML was all about pages that could change in response to basically any stimuli — whether it was the user, data from the server, a timer, who really cares.”

DHTML could do these updates without reloading the page, which at the time was a novel approach. “Everything happens on the client and you don’t have to go back to the server,” Isaacs explained in an interview promoting his 1997 book.

If this sounds familiar to developers of Single Page Applications (SPAs) today, it’s because Microsoft’s DHTML was the start of all that. It’s often thought that Ajax (Asynchronous JavaScript and XML) in the early 2000s was where this approach began. But it wasn’t Google that invented it with Gmail in 2004; the beginnings go back to Microsoft’s DHTML in 1997. That led to XMLHttpRequest a year or two later, and then into Ajax. But that’s a story for a future post.

Toward a DOM Standard

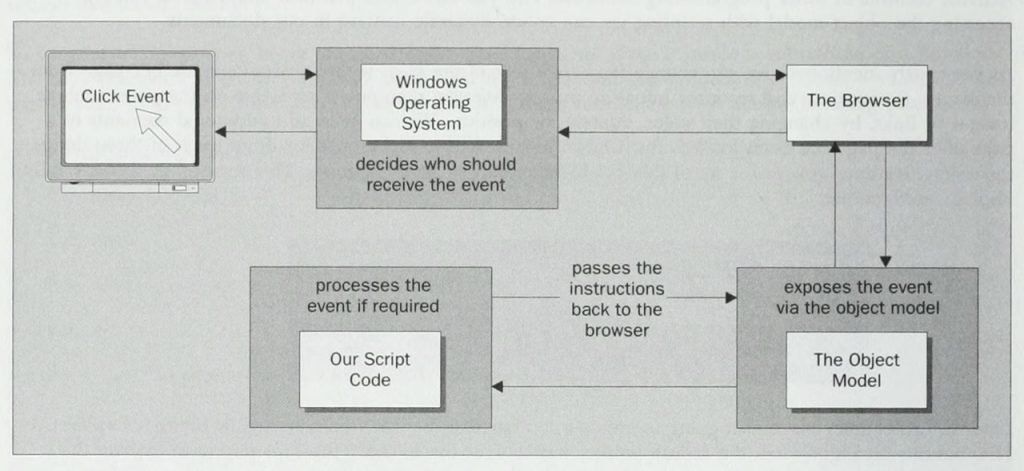

When Microsoft announced its new browser, Internet Explorer 4.0, in April 1997, it called DHTML “an open, language-independent object model.” This object model directly inspired the emergence of the W3C standard called the DOM — although there was some prior art that came from Netscape.

In previous browsers, versions 2 and 3, there existed an unofficial and fairly limited DOM that was later labeled “Level 0.” As Peter-Paul Koch wrote:

“The Level 0 DOM was invented by Netscape at the same time JavaScript was invented and was first implemented in Netscape 2. It offers access to a few HTML elements, most importantly forms and (later) images.”

We discussed these beginnings of the DOM in our post about JavaScript in 1996. In 1997, the evolution of the DOM entered into an intermediate stage — where developers knew that a standard web object model was needed, but the details were yet to be hashed out. Indeed, at this time Netscape and Microsoft had very different object models for their respective version 4 browsers. Here’s Koch again:

“Netscape and Microsoft chose to create their own, proprietary DOMs to provide access to layers and to change their properties (their position on the page, for instance). Netscape created the layer model and the DOM document.layers, while Microsoft used document.all.”

It wouldn’t be until 1998, with the version 5 browsers and a W3C specification, that the DOM would reach Level 1. It became a W3C specification in October of that year (and it didn’t just cover HTML; it was also for XML, another emerging W3C standard).

Early discussions about the DOM were happening on the W3C mailing lists by April 1997. This message on 15 April 1997, in response to someone asking what this new-fangled DOM was, indicated that Scott Isaacs and Microsoft were influencing the emerging standard:

“It is a (very) new W3C WG – they don’t appear to have their own page up yet. I talked to several of the participants at WWW6 and Scott Isaacs from MS was kind enough to demonstrate the MSIE reference implementation. It is very powerful concept – but we’re a ways from seeing a standard I expect.”

At around the same time, a new W3C mailing list was started for discussions based on the DOM working group. Lauren Wood, chair of this group, posted the first message on 25 April 1997:

“The first pages about the Document Object Model are now available. Point your favourite browser at http://www.w3.org/pub/WWW/MarkUp/DOM”

A copy of that page from June 1997 exists on the Wayback Machine. It defined the DOM as follows:

“The Document Object Model is a platform- and language-neutral interface that will allow programs and scripts to dynamically access and update the content, structure and style of documents. The document can be further processed and the results of that processing can be incorporated back into the presented page.”

So it was clear from the get-go that the DOM was an interface for scripts and programs (which enabled interactive content). What’s most interesting in this early version of the W3C DOM documentation, is that DHTML is cited as the motivation for the project:

“‘Dynamic HTML’ is a term used by some vendors to describe the combination of HTML, style sheets and scripts that allows documents to be animated. W3C has received several submissions from members companies on the way in which the object model of HTML documents should be exposed to scripts.”

The Release of IE4

When Internet Explorer 4 was released in October 1997, it was the first browser to demonstrate a full-page object model — as described above, basically a prototype of the W3C DOM spec that would be released a year later. In these respects, IE4 was a revolutionary product for web developers. As described in 2011 by Jeremy McPeak:

“IE4’s designers wanted to turn the browser into a platform for Web applications. So they approached IE4’s API like an operating system’s—providing a near complete object model that represented each element (and an element’s attributes) as an object that could be accessed with a scripting language (IE4 supported both JavaScript and VBScript).”

Netscape Navigator 4 had a limited DOM by comparison. It was perhaps most noticeable in how each browser moved elements around a web page. Netscape used a proprietary technology called “layers,” which animated content on a web page using JavaScript (as discussed in our previous post). Compare this to how IE4 did it, as explained here by Scott Isaacs:

“Internet Explorer uses an object called the All Collection to move elements around. Netscape uses a different collection called Layers. And the difference really comes back into the fundamentals of what both browsers did. Microsoft, in the All collection gives you access to every element and does not distinguish between whether it’s positioned or not. With Netscape, you can only program positioned elements – elements located at specific points on your screen. These few elements are packaged in a separate collection called Layers.”

All that said, there was a lot that IE4 either didn’t support yet (e.g. CSS borders) or that was non-standard and unique to IE (e.g. the infamous Marquee element). Despite these compatibility issues, Mudry concludes in his book that IE4 is “a very powerful and robust browser” and that its ideas on dynamic HTML were superior to Netscape’s. Crucially, those ideas were picked up and carried forward by the W3C — “this time Microsoft has standards on its side,” is how Mudry put it.

The Legacy of DHTML

What’s striking looking back on 1997 is that, for the first time, it wasn’t Netscape setting the agenda for web development. Microsoft’s object model was superior and it formed the basis for the W3C standard. Netscape also tried to create an alternative to CSS, with a JavaScript-powered styling mechanism called JavaScript-Based Style Sheets (JSSS). Although it was submitted to the W3C, JSSS went nowhere. Eventually Netscape moved to support the emerging CSS and DOM standards, but it was surprising that they ceded the floor to Microsoft in DOM innovation.

Nowadays we don’t use the term “DHTML” and much of the interactive functionality that it promised in 1997 became subsumed into the W3C DOM standard (which itself went through many iterations over the years, but that’s another series of posts). We can look back on DHTML now as being the impetus for the development of a standard programmatic interface to HTML pages. Craig Knuckles and Joe Hummel put it nicely in an academic paper from 2005:

“Perhaps the most important legacy of DHTML is that it has introduced a new paradigm in GUI development — create a GUI using a markup language, and script the events using some programming language.”

In the next post in this series, we’ll explore how the DOM became a standard in 1998 and how the leading browser companies adapted to it — particularly Netscape, which had the most work to do to re-align.

Read next: 1997: Netscape Crossware vs the Windows Web

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.