1997: Netscape Crossware vs. the Windows Web

After Microsoft upped the ante in the browser market in 1996 by integrating Internet Explorer 3.0 into Windows, Netscape began the new year with a renewed focus on the open web.

After Microsoft upped the ante in the browser market in 1996 by integrating Internet Explorer 3.0 into Windows, Netscape began the new year with a renewed focus on the open web. Co-founder and CTO Marc Andreessen, along with the Netscape product team, introduced a new strategy called “crossware”:

“Crossware describes on-demand applications that run across networks and operating systems, and are based entirely on open Internet standards like HTML, Java, and JavaScript.”

Since Netscape’s core product was a browser — by now the primary gateway to the Internet — this strategy made perfect sense. The problem was, only one of the three technologies Andreessen mentioned was a certified open standard at the time (HTML). Java was a proprietary programming language controlled by Sun Microsystems, while JavaScript was still owned by Netscape.

Java was destined to stay propietary, but for JavaScript the standardization process had at least begun.

ECMAScript

To turn JavaScript into an open standard, Netscape approached a European computing standards body called the ECMA in November 1996. By early January 1997, the so-called ECMA Committee #39 released version 0.3 of the proposed standard. Since it couldn’t be called JavaScript (“Java” was a trademark of Sun), the language had been rather awkwardly named ECMAScript. There was little contention, however, between Netscape and Microsoft regarding the core specification. From the introduction to v0.3:

“There are three known implementations of ECMAScript in common use today: Netscape JavaScript 1.1, Borland JavaScript 1.1 and Microsoft JScript. All three implementations share a great deal in common.”

The main players, Netscape and Microsoft, were happy to let the spec wonks take the lead. It was smooth sailing and the first edition of ECMAScript was released in June 1997. But while the specifications process was straight forward, how ECMAScript would be implemented inside the browser was a much more contentious topic. Even before the new standard had been ratified, Marc Andreessen was sounding off in his column about browser security when running JavaScript:

“Even as JavaScript’s existing features are standardized, Netscape is continuing to drive the technology forward. Netscape Communicator adds a capabilities-based security model that gives the user flexible control over which resources a signed script may access. Like Java, JavaScript was designed to run safely over the Internet, so by default it runs only in a protective “sandbox” where it cannot access local resources such as individual hard drives.”

This was a not-so-subtle dig at the known security flaws of Microsoft’s ActiveX platform, which could access local Windows resources (sometimes to the user’s detriment).

The browser wars were heating up.

Components: JavaBeans vs. ActiveX

Netscape’s DevCon 3, its third developer conference, was held from 11-13 June, 1997, in San Jose, California.

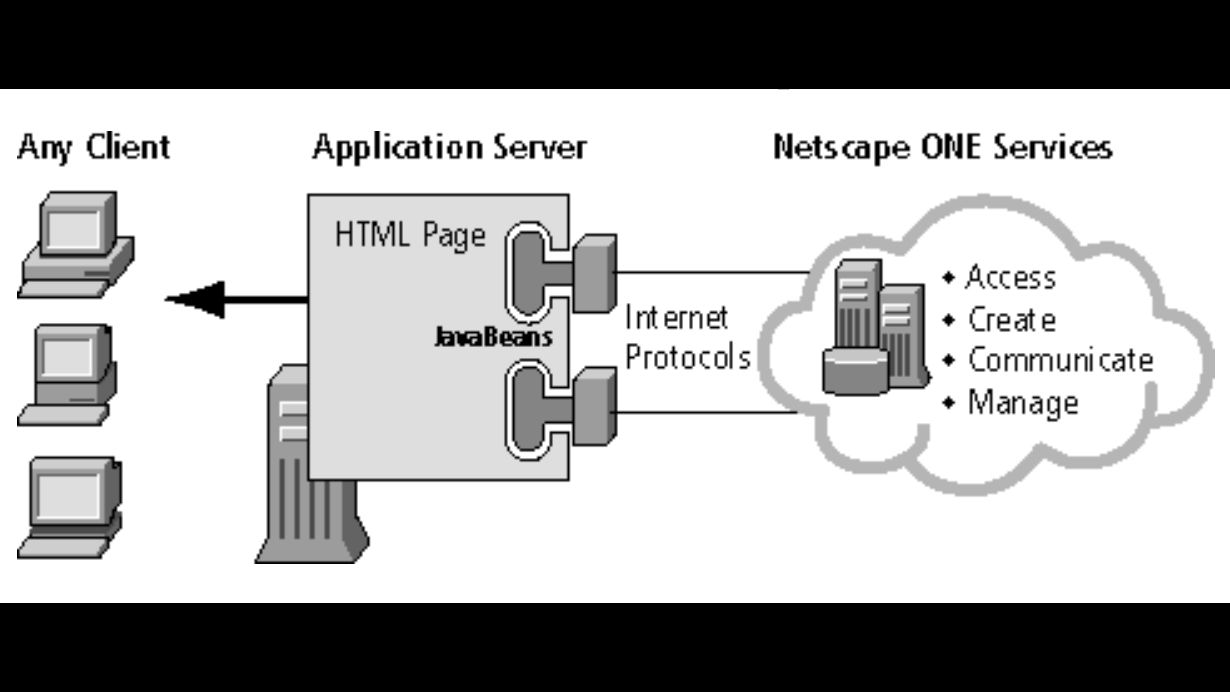

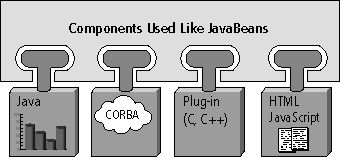

One of the key announcements was that Netscape would be using Sun’s JavaBeans technology as the component architecture for its web development platform (which went by the name of Netscape ONE). JavaBeans were blocks of Java code that could be inserted into web applications. It was Netscape’s response to Microsoft’s ActiveX component model, which had tight integration with the Windows OS. By comparison, JavaBeans were cross-platform. Java was famously a “Write Once, Run Anywhere” programming language; and with JavaBeans, “Re-Use Everywhere” was appended to that catchphrase.

As described in the JavaBeans API specification in 1997:

“The goal of the JavaBeans APIs is to define a software component model for Java, so that third party ISVs can create and ship Java components that can be composed together into applications by end users.”

The spec noted that some JavaBean components “will be used as building blocks in composing applications,” while others will “be regular applications, which may then be composed together into compound documents” (it gave the example of a spreadsheet being embedded inside a web page).

For Netscape, JavaBeans were a convenient way of introducing powerful desktop application functionality into its browser. This was particularly important for enterprise applications, which ran on corporate-controlled networks called “intranets.” This form of app development was a traditional strength of Microsoft, given its OS and office software dominance in the market. Netscape realized that the only way it could compete with Microsoft in enterprise software — and by extension attract more app developers to its platform — was to partner with Microsoft’s competitors in enterprise software, like Sun and Oracle.

JavaBeans enabled developers to access data and functionality in applications outside of the browser, but connected via the intranet — such as messaging, directory, security, publish and databases.

Although Netscape heavily relied on Sun and its Java technology, it also wasn’t afraid to change — or even subvert — the process of using it. As part of the Communicator suite, Netscape released a program model called BeanConnect. It enabled multiple Java objects to be embedded into an HTML page, optionally using JavaScript. Netscape positioned this new feature as an alternative to using the Java applet model:

“Currently, developers who provide Java components and objects for crossware applications are mandated to use Applet and related classes in the Sun java.applet package to create an application, and must use the tag to embed the application in an HTML page. While the applet model works well for simple, self-contained Java applications, each such applet is restricted to a single AWT Frame object, runs in the page where it is embedded, and cannot participate in HTML form posting. The applet model does not provide a shared execution context for multiple objects. Finally, applet lifetime is not well-defined, and cannot be controlled by the application developer.”

The Networked Enterprise

A couple of months earlier, in April 1997, Andreessen had outlined his vision for Netscape inside the enterprise. The whitepaper listed a series of code-named services, like Mercury, Apollo and Compass. For example, Mercury was the code name for the next version of Netscape Communicator, “targeted for early 1998.” Unfortunately, at times this came across as buzzword bingo. For instance:

“Apollo is complemented by Palomar, a first-of-its-kind visual crossware development tool that allows complex crossware applications to be quickly and easily designed and deployed.”

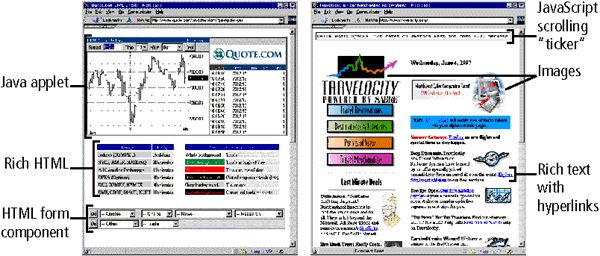

There was a creeping complexity, too. Netscape Navigator 4.0, released during DevCon in June 1997 as a part of the Communicator suite, was described as having an “enhanced application environment” in the whitepaper. Among its features:

“Navigator 4.0 builds in a CORBA Object Request Broker (ORB) to support CORBA/IIOP applications and faster Java support across platforms, including Windows 3.1.”

As described in a June 1997 Wired article, Common Object Request Broker Architecture (CORBA) was “a model designed to allow applications to communicate with one another no matter where they are located or who has designed them.”

Netscape’s strategy was to enable developers to build “cross-platform applications that can be deployed on a browser”; but it was unclear at the time how well JavaBeans and CORBA would integrate with Netscape’s browser (let alone competing browsers).

Regardless, in a developer roadmap paper released for DevCon, Andreessen doubled down on the portability and interoperability of its approach:

“Together with CORBA and IIOP, the Internet standards for communication between JavaBeans, it is now possible to develop and deploy service-based applications that are portable, in that they can run on any platform, and are interoperable, in that they can interoperate with each other and leverage a variety of back-end systems and services.”

Although all of this was still relatively unproven in 1997, in hindsight Netscape’s web application strategy set the standard for how all web technologies have been positioned ever since — as cross-platform and interoperable. It’s more true than ever for modern day web apps, in comparison to ‘walled garden’ platforms like Facebook or Apple’s iOS.

Developer Tools

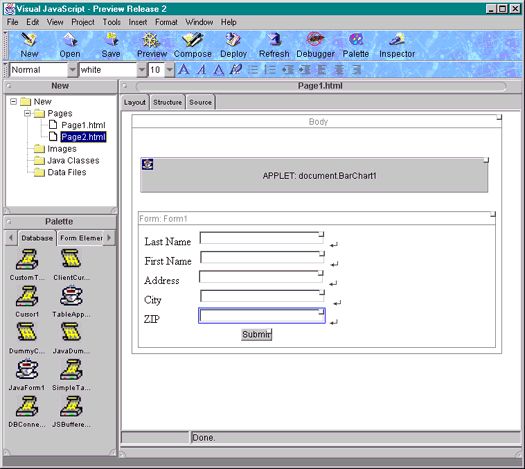

With the added complexity of Netscape Communicator — less politely referred to as “bloat” — Netscape took a leaf out of Microsoft’s book in order to ease web developers into the world of JavaBeans and CORBA. At DevCon 3, Netscape announced Netscape Visual JavaScript, a visual tool for “rapid crossware development.” It was an obvious clone of Microsoft’s Visual Basic tools.

In fact, Microsoft had already one-upped Netscape in 1997 with Visual Studio 97, which had been released in January of that year. Such tools were called IDEs (integrated development environment) and Microsoft Visual Studio 97 was the very first version of a product that continues to be offered to this day (the latest version, as I write, is Visual Studio 2019).

An interesting sidenote to the tooling: as part of their promotions, both Netscape and Microsoft laid claim to the term “Dynamic HTML.” Netscape defined it as “combinations of HTML, style sheets (including CSS1 and HTML positioning and layering), and JavaScript” and it was supported in the Visual JavaScript product. Meanwhile, part of Microsoft’s Visual Studio 97 was Visual InterDev, a tool “for building dynamic Web applications.” Of course the two versions of Dynamic HTML (soon to be known as DHTML) didn’t always overlap. But that’s a whole other story, which I get into in a separate post.

Conclusion

Looking back on it over two decades later, 1997 was the year when web development began to get overly complicated. That’s because web applications were the new battleground for the two main browser companies, and each had their own component model and differing view of what “dynamic” web pages entailed.

JavaScript / ECMAScript was a key glue language for both Netscape and Microsoft, but it was at that point overshadowed by more powerful web programming languages (Java for Netscape, and the emerging Active Server Pages paradigm for Microsoft).

All of this development divergence meant that browser incompatibility was becoming an increasing source of frustration for web users, a theme we will explore further in upcoming posts.

Read next: 1998: Open Season with Mozilla, W3C’s DOM, and WaSP

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.