1997: JavaScript Grows Up, Developers Push Boundaries

Pointy-headed technical analysis of JavaScript was not what was required in 1997. Developers of that era needed practical guidance and code samples. Also, Brendan Eich moves on from Netscape.

By the start of 1997, JavaScript had become a regular topic for tech reference websites and books. Nick Heinle was perhaps the epitome of this, as he began 1997 with a column on WebReference.com called JavaScript Tip of the Week, released an O’Reilly book in August 1997 entitled Designing with Javascript: Creating Dynamic Web Pages, and ended the year running a website called WebCoder.com (owned by CMP, the computer magazine publisher).

Oh, and Nick Heinle was 17 years old! There’s something very 90s about teenage developers leading the way with web scripting (you may recall Matt Wright from a previous post, the high school student who ran a popular CGI scripting directory).

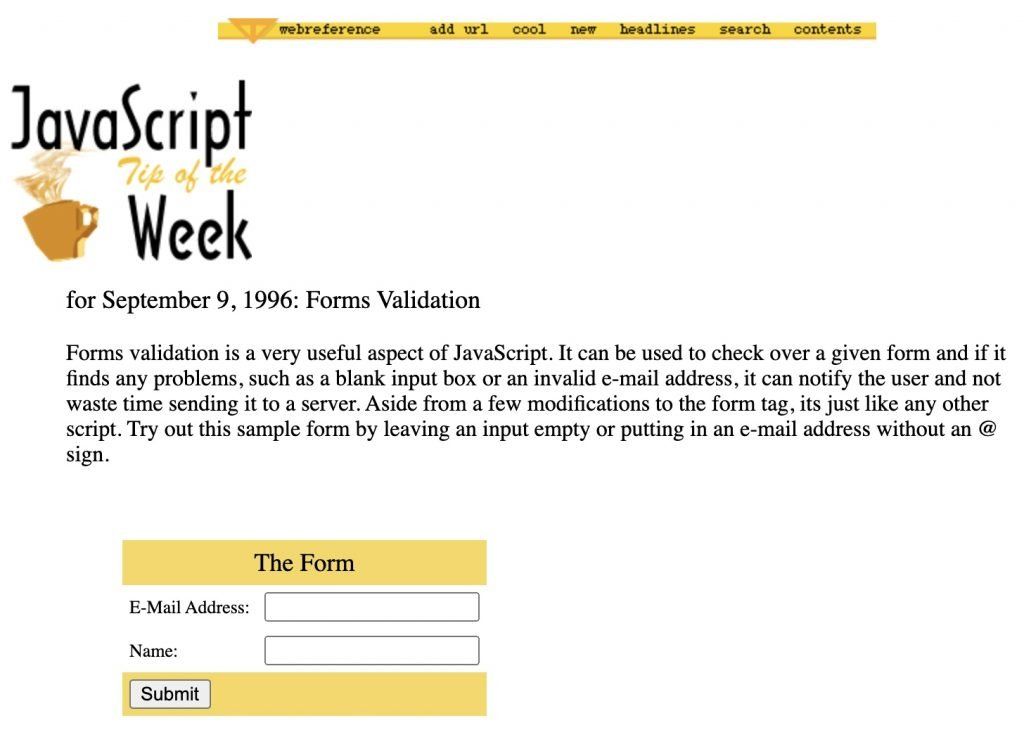

During the first half of 1997, the main browsers were Netscape Navigator 3 and Internet Explorer 3. Heinle’s JavaScript Tip of the Week articles covered fairly basic JavaScript functionality for these browsers, such as forms validation and how to use cookies.

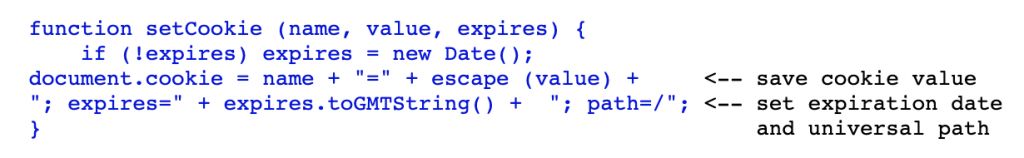

In the cookies article, Heinle pointed out that the “most prevalent code out their [sic] is Bill Dortch’s.” Having said that, Heinle wanted to write his own functions.

As teenage computer wizards are wont to do, Heinle boasted that his functions were “twice as fast as Dortch’s.” That may’ve been so (I don’t know for sure), but it turns out Dortch was doing some much more innovative things with JavaScript around this time.

JavaScript inventor Brendan Eich later pointed to a gallery website developed by Dortch in 1996 that Eich said was an “SPA [Single Page Application] years before Ajax.” Dortch himself wrote in 1996, about the Whitetail Butte Gallery website, that “JavaScript buffs will be interested to note that all the pages of WBG are generated on the fly, except for the artist biographies.”

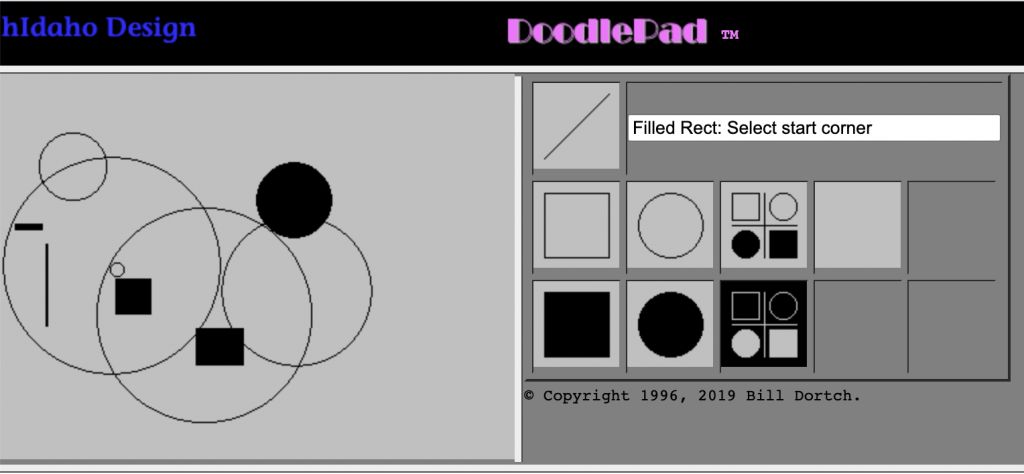

Although we can only view the gallery website now via the Internet Archive, we can see emulations of Dortch’s JavaScript innovation for two other websites from the same time period. The first, DoodlePad, was described by Dortch as “a simple JavaScript drawing app I wrote in February, 1996.” It may’ve been simple to use (and you can try for yourself in an emulator), but the code behind the scenes was very sophisticated for this period.

“As far as I know, DoodlePad was the first pure-JavaScript drawing app, and likely the last until browser support for the SVG image format came along circa 2001,” wrote Dortch. Other web drawing apps of the era were created using Java applets or Adobe Flash (and the latter was brand new; it had been released in early 1996). Creating such an app using JavaScript was “nearly impossible,” Dortch wrote — emphasis on nearly.

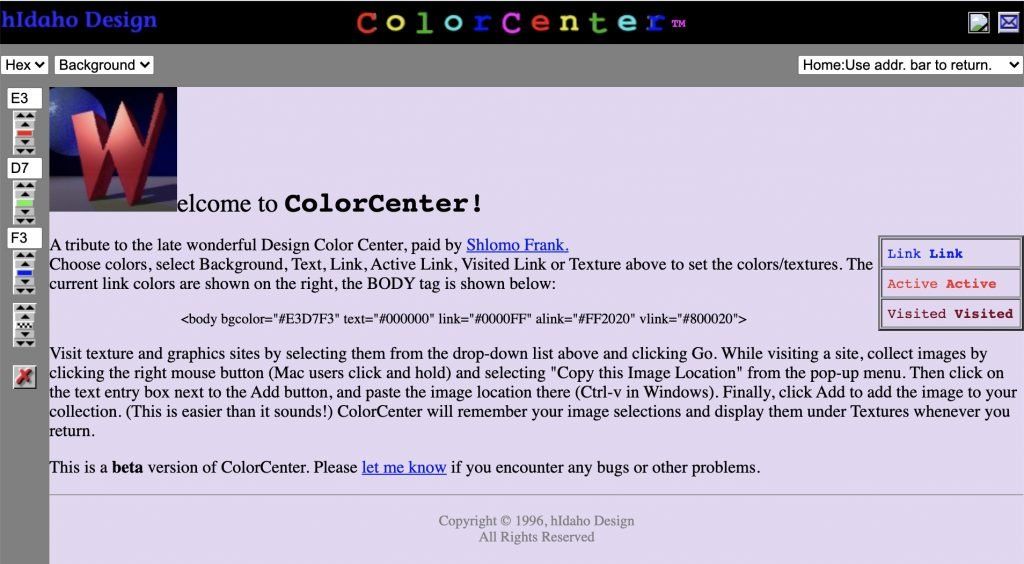

Another Dortch creation from 1996 was ColorCenter, which allowed the user to dynamically adjust the colors inside a browser window.

Dortch noted that “by later in 1996” he had “moved on to mainly Java back-end work.” A pity, as he was clearly pushing the boundaries of JavaScript.

The New Tricks of JavaScript

By the time Nick Heinle’s JavaScript textbook was released in August 1997, Netscape had released version 4.0 of its browser. Microsoft IE 4.0 would be released a couple of months later, but Heinle made sure to account for both new browsers in his book.

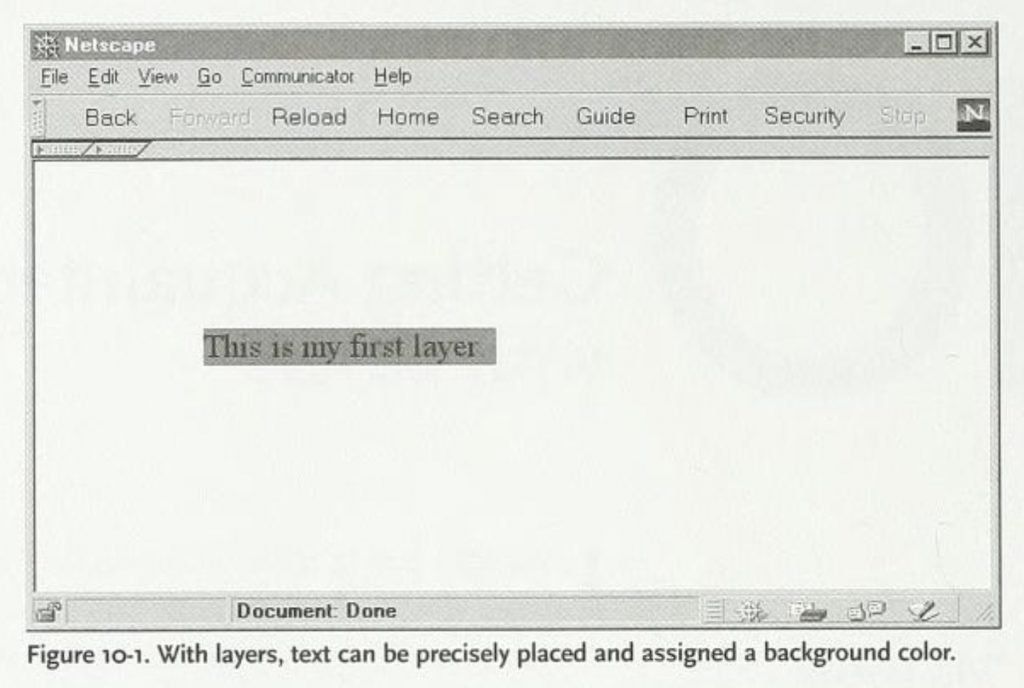

When Netscape Navigator 4.0 launched in June, it came with a new version of JavaScript labelled 1.2. One of the features that JavaScript 1.2 introduced was layers. In one of its technical documents, Netscape described the layer object as “a positioned block of HTML content.” The idea was that you’d be able to modify that block of content and place it anywhere on a web page. The Netscape document explained:

“For each layer in an HTML page (whether it is defined with the tag or as a style whose position property is either absolute or relative) there is a corresponding JavaScript layer object. You can write JavaScript scripts that modify layers either by directly accessing and modifying property values on the layer objects, or by calling methods on the layer objects.”

Heinle devoted one of the chapters of his book to this topic. In it he described a way to “use layers and JavaScript to create a complex animation effect.”

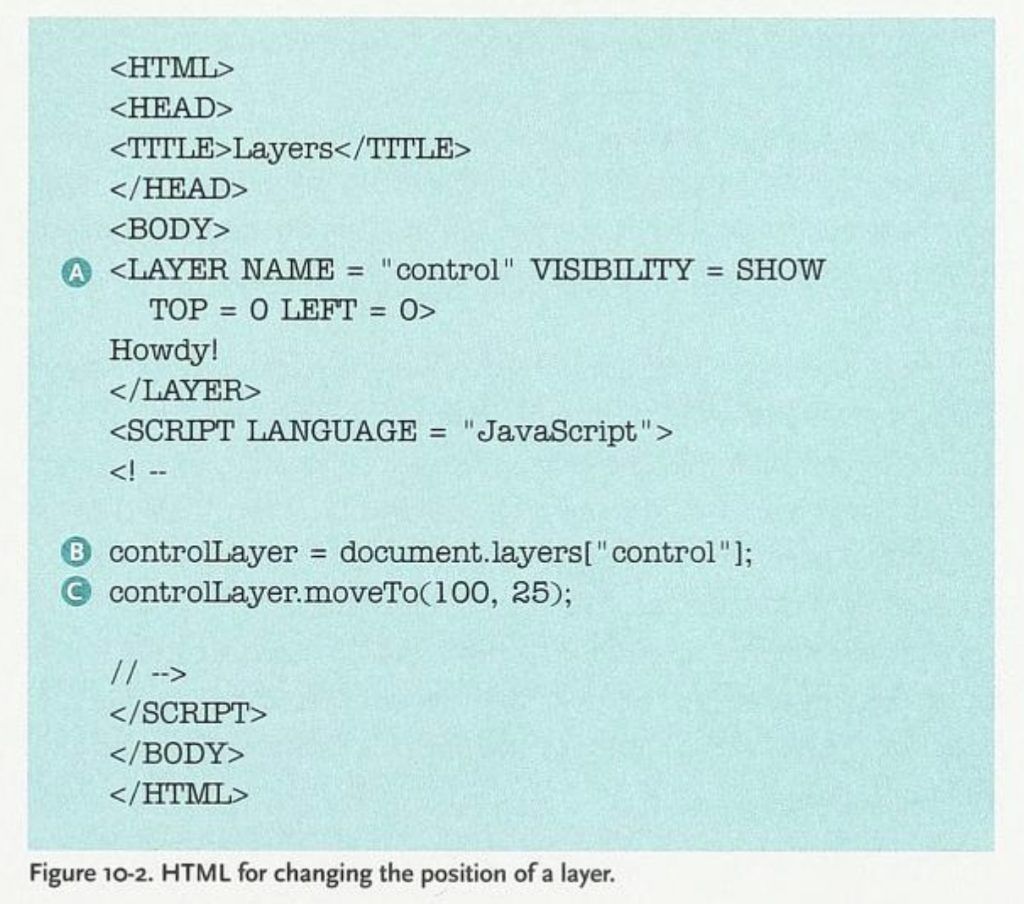

After explaining the basics, Heinle then showed a variety of coding techniques to control a layer:

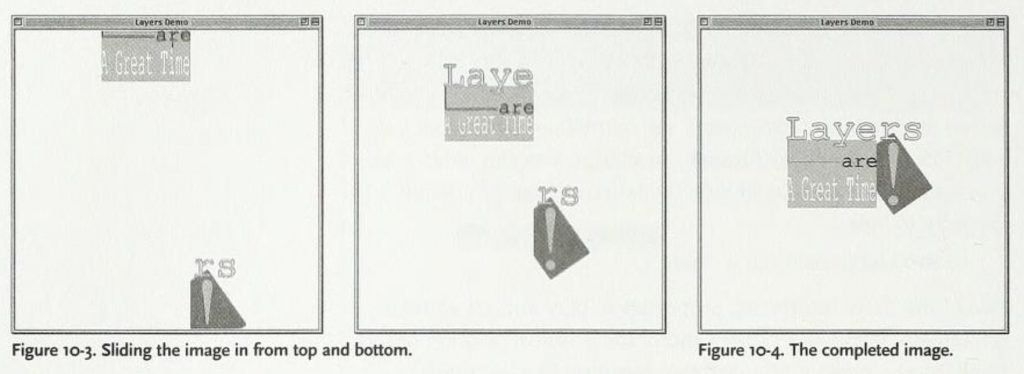

The complex animation effect that Heinle illustrated was an image moving across a web page, from bottom to top:

He goes on to show how you can do even trickier animation on a web page using the layer object. The chapter is short, but practical. You can see why the book was fairly popular in 1997 and going into 1998 — Heinle’s writing style is engaging without ever being wonky, and the diagrams and code examples supplied are excellent visual guides to working developers of that time.

However, Heinle’s relative inexperience shows when he brushes off in-depth explanations of how the technology works (“Explaining exactly how this works would require a crash course in basic trigonometry”). But then again, pointy-headed technical analysis was not what was required in 1997. Developers of that era needed practical guidance and code samples. So in that sense, there’s something refreshing about Heinle’s willingness to experiment with new JavaScript features such as layers. It also perhaps explains why teenagers were among those at the forefront of documenting web development in the 1990s — they had time to mess around with the latest web technologies, didn’t accept established code (ref: Heinle’s attitude towards Dortch), and weren’t afraid of trying new things to see what could be accomplished on a website. Although to be fair, the same could be said about Dortch.

Heinle ends the chapter with this line, which I’d happily nominate as a motto for web developers of all eras:

“If this sets your head “spinning,” don’t worry: a few minutes of experimentation and this will quickly come into focus.” [page 175]

Brendan Eich Moves On

By the end of 1997, JavaScript inventor Brendan Eich had moved on from active development of Netscape’s fast-growing web scripting language. By his own account, the JavaScript team had grown “large by end of 1997,” so he decided to take a break from JavaScript and join the nascent Mozilla organization. By that point, JavaScript was one of two main client-side web programming languages, alongside Microsoft’s VBScript. There were other options, such as Tool Control Language (Tcl, pronounced “tickle”), but the web development agenda of this era was increasingly being set by the two leading browser vendors: Netscape and Microsoft.

It had been a busy year for Eich. The same month that JavaScript 1.2 was released as part of Netscape Navigator 4.0 (June 1997), the first edition of ECMAScript was released — the open standard based on JavaScript, with input from other companies like Microsoft, Borland and Sun. Eich had a big hand in both developments.

At the same time, Eich was being influenced by other web trends happening around him — such as the rise of Python as a scripting language. He later wrote:

“JS1.0 in 1995 was under Perl influence; JS1.2 in 1997 fell more under Python influence.”

By that he meant that JavaScript 1.2 was influenced by the language design choices of Python. Later, in 2006, the ECMAScript wiki recorded that JavaScript was “standing on Python’s shoulders” by borrowing important programming concepts like “structured value-generating continuations and a general iteration protocol.” Eich himself wrote on the wiki that Python “has covered the same thought-space and recorded the arguments” required to grow JavaScript.

Programming theory is beyond the scope of this website, but it’s worth noting that Python is well regarded for its conciseness and ease-of-use. On the other hand, Perl’s best known motto is “There’s More Than One Way to Do It” — implying that it’s not so easy to decide how to use it!

Eich wasn’t the only one being swayed by Python over Perl during the time JavaScript 1.2 was being released. Eric Raymond, author of the famous computing book The Cathedral & The Bazaar, also discovered the joys of Python in 1997, calling it “a more elegant scripting language” than Perl.

The point is, we can see in hindsight that JavaScript had become a sophisticated language by 1997 — with new features like layers adding a further dynamic dimension to its capabilities. The language was also increasingly being used in combination with HTML, CSS and other web technologies to enable something that Netscape labelled “Dynamic HTML.” Microsoft had its own definition of that term, but I’ll delve into both in the next article in this series.

Read next: 1997: The Year of DHTML

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.