1996: JavaScript Annoyances and Meeting the DOM

Other than homepages sprinkled with little animations, scrolling text, and embedded digital clocks, adventurous corporate webmasters began to experiment with JavaScript in early 1996.

The Netscape Navigator 2.0 browser was finally released in March 1996, almost a year after Brendan Eich joined Netscape with the express purpose of creating a scripting language for the web. He’d developed the prototype of JavaScript over a ten day period in May 1995 and spent the rest of the year embedding it into the browser. JavaScript was publicly announced at the end of 1995, as part of Netscape’s beta launch of Navigator 2.0.

As well as JavaScript, Navigator 2.0 added support for Java applets, plug-ins, frames (“multiple documents on one page”) and more. It was a significant leap forward in functionality from the last major Navigator release, 1.22 in August 1995.

For all of the technical wizardry in Netscape Navigator 2.0, when it was first released JavaScript was put to use in fairly trivial ways — scrolling text, silly animations, tricks with colors (fading, rainbow effects, and so on). As Eich put it in a 2005 presentation, “JS caught on like a bad cold (per plan!).” He bemoaned the proliferation of “annoyances” that JavaScript enabled, a complaint that likely prompted his Netscape colleagues to create a satirical web homepage for him.

Other than homepages sprinkled with little animations, scrolling text, and embedded digital clocks, some of the more adventurous corporate webmasters began to experiment with JavaScript in early 1996. Sometimes to the befuddlement of their website users.

In an exchange on the W3C www-html public mailing list in February 1996, someone named Christian Gerard posed this question to the group:

“Ok I’ve been listening in to many conversations lately about different types of web pages. I recently took a look at Rogers Telecommunications based in Toronto Canada. ould someone PLEASE tell me how in the heck they were able to send information to me through the ADDRESS line in the Netscape browser? they also had multiple images over each other…

Could someone please tell me how they did that—? And how the heck can I DO THAT??”

While we can no longer view the version of www.rogers.com from February 1996, the Wayback Machine has a copy from November 1996 that includes a “Multi-Media” section and “Virtual Gallery.” So we can assume the design team were web savvy and a bit ahead of the curve for corporate websites.

In response to Gerard’s question, someone pointed out that JavaScript was being used on rogers.com. However, not everyone on the list was impressed with the user experience of this nascent technology:

“You will not, however, glean what caused them to think that text scrolling slowly and choppily across the bottom of a window was a good idea. (Just for fun, sit there and watch it go for a minute or two. JavaScript runs out of memory and, in my admittedly limited tests, locks up Netscape about half the time.)”

Another commenter called the text scrolling feature a “bit o’ fluff,” adding that “Netscape’s homepage has it too.”

But while many early JavaScript features were dismissed as being mere “annoyances” (to use Eich’s term), JavaScript could also be put to use in more pragmatic ways. For instance, adding a back button to a page with multiple frames — so that when pressed, the ‘back’ function is applied to just one frame and not the entire page.

A little context: frames were another new feature in Navigator 2.0 and they allowed you to embed two or more separate HTML documents in one web page. Most commonly, frames were used to put a persistant menu on the left side of the page, with the primary content in the second frame on the right (usually taking up the bulk of the page width). You could also have your header and footer in separate frames. In later years, web designers would use CSS to do this — but in early 1996, frames were the go-to option.

Returning to the back button example, one way to utilise JavaScript in frames was to add the button (or a simple text link) to the content frame. When clicked, it took the user back to the previous content page without affecting the other frames.

Introducing the DOM

The JavaScript that debuted in Navigator 2.0 in March 1996 was version 1.0 of the new scripting language. One of the innovations of JavaScript 1.0 is that it led to the creation of what would become a fundemantal model of web programming: the Document Object Model (DOM). As explained in JavaScript: The First Twenty Years, the DOM was derived from the very first JavaScript library:

“JavaScript 1.0 comes with a library of built-in functions, objects, and constructors. The library defines a small number of general-purpose objects and functions along with a larger set of host-specific objects and functions. For Netscape Navigator [2.0], host objects provided a model of portions of the current HTML document. These APIs ultimately became known as the Document Object Model (DOM) level 0.”

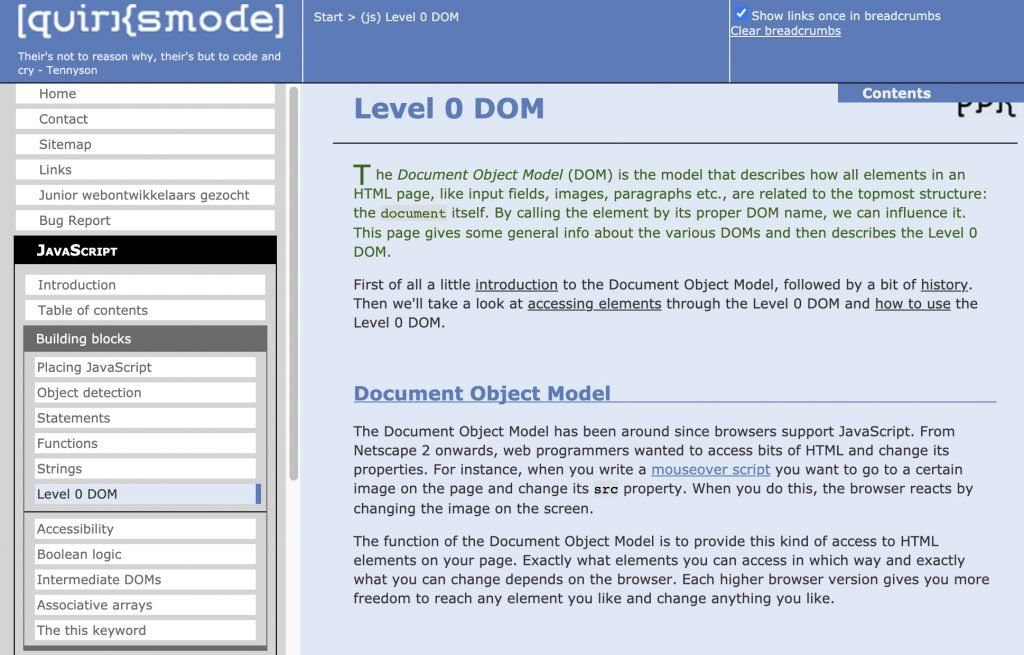

Peter-Paul Koch defined the DOM as follows:

“The Document Object Model (DOM) is the model that describes how all elements in an HTML page, like input fields, images, paragraphs etc., are related to the topmost structure: the document itself. By calling the element by its proper DOM name, we can influence it.”

He went on to note about level 0:

“The Level 0 DOM was invented by Netscape at the same time JavaScript was invented and was first implemented in Netscape 2. It offers access to a few HTML elements, most importantly forms and (later) images.”

Incidentally, Koch’s website from that era makes heavy use of frames — and he offers a sturdy defence of that decision. Other than claiming that “frames add usability to my site” — primarily via the persistant menu — he notes that JavaScript enables him track the user across different frames:

“Frames allow me to preserve state between pages. I can add simple JavaScript routines that remember where the user has been.”

Starting from Navigator 2.0, web designers could include multiple JavaScript features in a single web page (and indeed in frames). Each code insert was demarked by using the <script> tag in HTML. The order of execution was also important at this stage, as explained in JavaScript: The First Twenty Years:

“In Netscape 2, the JavaScript code for each <script> element is parsed and evaluated in the order they occur within the page’s HTML file. In later browsers <script> elements may be tagged for deferred evaluation which lets the browser continue processing HTML while it waits for the JavaScript code to be retrieved from the network. In either case the browser evaluates one script at a time.”

A final key concept worth noting here is the event-driven model of JavaScript 1.0, which was inspired by Apple’s HyperCard. Again from ‘First Twenty Years’ (I’m quoting a lot from this ebook firstly because Brendan Eich himself is a co-author, but also because the technical explanations usually cannot be improved upon):

“Interactive JavaScript Web pages are event-driven applications where the event loop is provided by the browser. HyperCard inspired Brendan Eich to use the concept of events in the original Netscape 2 DOM design. Originally events were triggered primarily by user interactions, but in modern browsers there are many kinds of events, only some of which are user originated.”

Growing Interest Among Developers

JavaScript 1.1 was released as part of Navigator 3.0, which debuted in August of 1996. JavaScript was still at this point a raw and buggy scripting language, mainly because of a lack of resources devoted to its development — Brendan Eich was “the only Netscape developer working fulltime on the JavaScript engine” for most of 1996. Indeed, JavaScript 1.1 “still consisted primarily of code from the 10-day May 1995 prototype.”

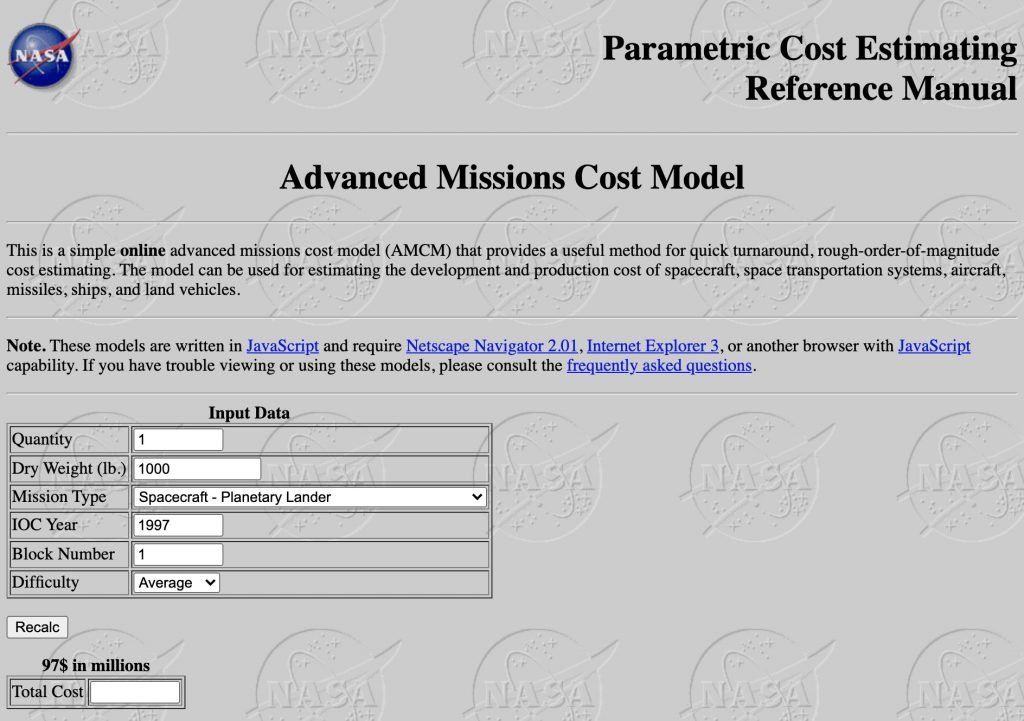

Even so, developer interest in JavaScript was growing and there were some excellent resources on the web by the latter half of 1996. For instance, the Java directory Gamelan listed 68 JavaScript resources and example applications in October 1996 — including several NASA cost models, a 3D graphics experiment called The Random Garden (“uses JavaScript to randomly place and texture objects in a VRML/Live3D scene”), and more complex applications such as this message board written in C that used JavaScript for “error checking and frame control.”

So by the end of 1996, the underlying power of JavaScript was beginning to be appreciated. The use cases for JavaScript were slowly expanding, despite Netscape apparently not having recognized its full importance yet. JavaScript was still seen as second fiddle to Java within Netscape. And to be fair, this view was widely held.

Java was “now the darling of the computer industry,” declared Charles Petzold in a New York Times article in September 1996. “Java’s biggest selling point is that little Java applications (called applets) can be incorporated in a World Wide Web page along with text and pictures,” he concluded. The article did not even mention JavaScript, which is a good indication of where it stood in the pecking order of web programming languages at the time.

In any case, Netscape’s strategic priorities now far exceeded animated GIFs, scrolling text and online form checking. The company’s multimedia ambitions for the web took on a grander tone in the second half of 1996, spurred on by increasing competition from Microsoft — whose Internet Explorer 3.0 browser was also released in August 1996. In the months following, Marc Andreessen began outlining a more expansive vision for Netscape. He talked up the addition of office, networking and video functionalities into a new suite of products to be released in 1997, called Netscape Communicator. I’ll look at the details of this in a follow-up post.

Read next: 1996: Netscape Lays the Groundwork For Web Applications

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.