1995: The Birth of JavaScript

JavaScript was invented in a two-week flurry in May 1995 by Brendan Eich, a newly hired developer at browser company Netscape. The idea was to extend the early Web beyond the limits of HTML.

JavaScript was invented in a two-week flurry in May 1995 by Brendan Eich, at the time a newly hired developer at browser company Netscape. The project was initiated by Netscape because of a desire to extend the early Web beyond the limits of HTML, the declarative markup language that web pages are written in. In particular, Netscape wanted to add interactivity to websites. JavaScript ended up being the solution and this post explores how that came to be.

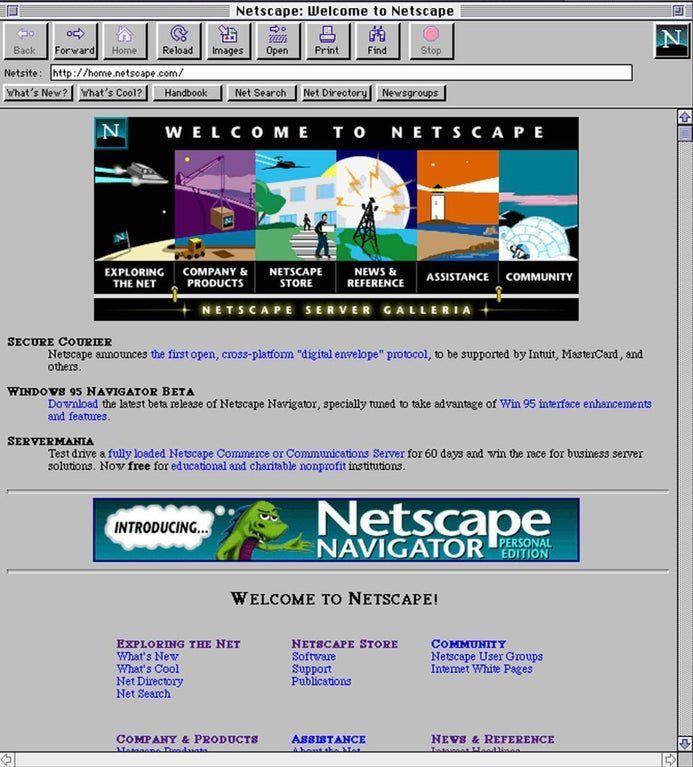

It’s hard to picture it now, twenty-five years after the fact, but at the start of 1995 web browsers had limited functionality. Netscape Navigator 1.0 had only just been released in December 1994. There was zero interactivity and support for the web standards of the day was patchy. As Adrian Roselli put it, version 1.0 “pre-dated frames, cookies, HTML tables (support came in 1.1), JavaScript, and support for any of the robust features of HTTP.” In other words: Netscape Navigator 1.0 supported HTML markup, but not much more than that.

1993-94: Back History of JavaScript

HTML was great for what it enabled — text documents presented to internet users inside a web browser. But Netscape was founded as a commercial operation (one of the web’s first) and it needed to find a way to provide added value to the nascent world wide web community. Given its origins as a graphical web browser, it was clear from the start what Netscape wanted to bring to the web: multimedia.

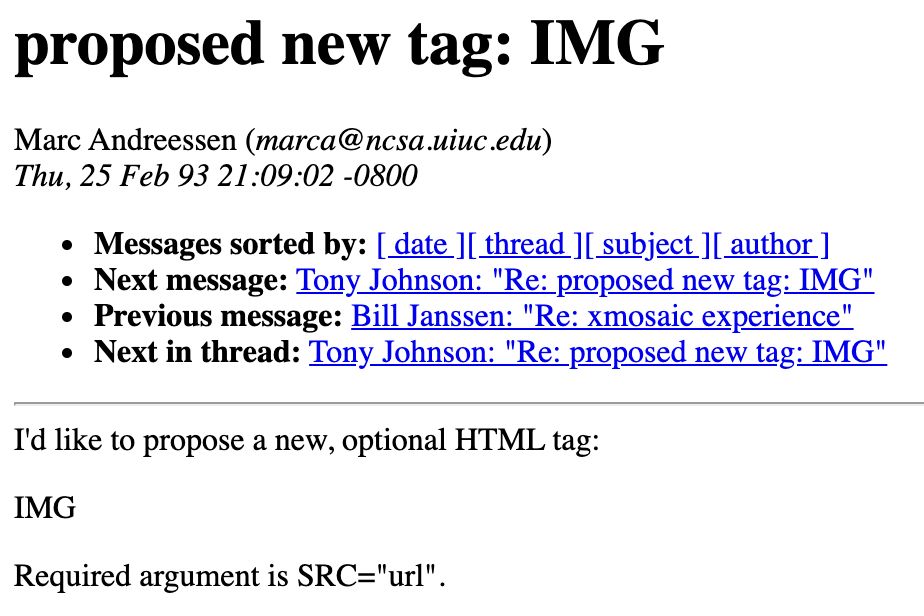

Netscape co-founder Marc Andreessen had already signaled his interest in adding multimedia elements to HTML as early as February 1993, with his suggestion to add an image tag to the specification. This was just a month after the initial release of Netscape’s predecessor, Mosaic — which Andreessen had co-created and was among the very first graphical web browsers.

At that point, early 1993, images could only be added by linking to them (when the link was clicked, the image would open in a new window). But Andreessen wanted inline images that would sit alongside text. The Mosaic team went ahead and added this functionality to their browser later in 1993, although the img tag wasn’t included in the W3C’s HTML specification until November 1995.

It’s also worth noting that prior to 1995, browsing the web was painfully slow — so even supporting the downloading of images was a big deal. In a 1994 review of the 0.9 version of Netscape’s browser (then known as Mosaic Netscape), David Brody wrote:

“Mosaic Netscape was developed with the aim of addressing the needs of bandwidth deprived computer owners like me. Those whose umbilical cord to the net is a 14,400 kbs modem, high speed by modem standards, but a snail when it comes to loading those cool color pictures and happening sounds.”

Brody listed Mosaic Netscape’s most significant feature as “the way it allows the user to go on browsing while it downloads items not immediately needed in the background.”

“Rather than forcing you to wait for a graphic to load, Netscape, loads a page’s text first, allowing you to scroll down the page or jump ahead to another URL while that nice looking, but perhaps not immediately necessary graphic, loads a piece at a time and without the need to wait for the page to paginate.”

The burden of loading images was so great in these early days, that in Navigator 1.0 you had the option of not downloading images by default. According to a manual at the time:

“You have the option, however, of turning off the automatic loading of images. You can do this by unchecking the Options/Auto Load Images menu item. When this menu item is unchecked, the images in pages do not automatically load. Instead, small icons are placed in the position on the page where an image would otherwise be.”

Many early web users will remember seeing those little image icons. You often had to hesitate before clicking on them, in order to make a quick mental calculation of how much time and bandwidth you had available!

So in Navigator 1.0, the focus was on managing basic multimedia elements (images, sound) in an age of super slow modems. But by the time 1995 rolled around, it was time for Netscape to take the next step in its multimedia plan: interactivity.

This time though, Netscape couldn’t just tweak the HTML spec. That’s because adding dynamic components to web pages could not be done with HTML alone. What was needed was a programming language that would add extra functionality to web pages, by way of code insertions into the HTML.

1995: Enter Eich…and Java

As told in JavaScript: The First Twenty Years, Brenden Eich joined Netscape in April 1995. He was hired because of his background developing “small special-purpose languages that supported kernel and networking programming tasks.” He’d actually been offered a job at Netscape when the company had launched, in April 1994 — likely because he’d previously worked for Netscape co-founder Jim Clark at Silicon Graphics. He’d turned it down back then, but took the job a year later when given the chance to implement a scripting language for web pages.

However, Eich didn’t think he’d have to write a new language from scratch. There were existing options available — such as the research language, Scheme, or a Unix-based language like Perl or Python. So when he joined, Eich “was expecting to implement Scheme in the browser.” But the increasingly fractious politics of the software companies of the day (it was, basically, everyone against Microsoft) soon saw the project take a more creative turn. Long story short, Netscape created an alliance with Sun Microsystems.

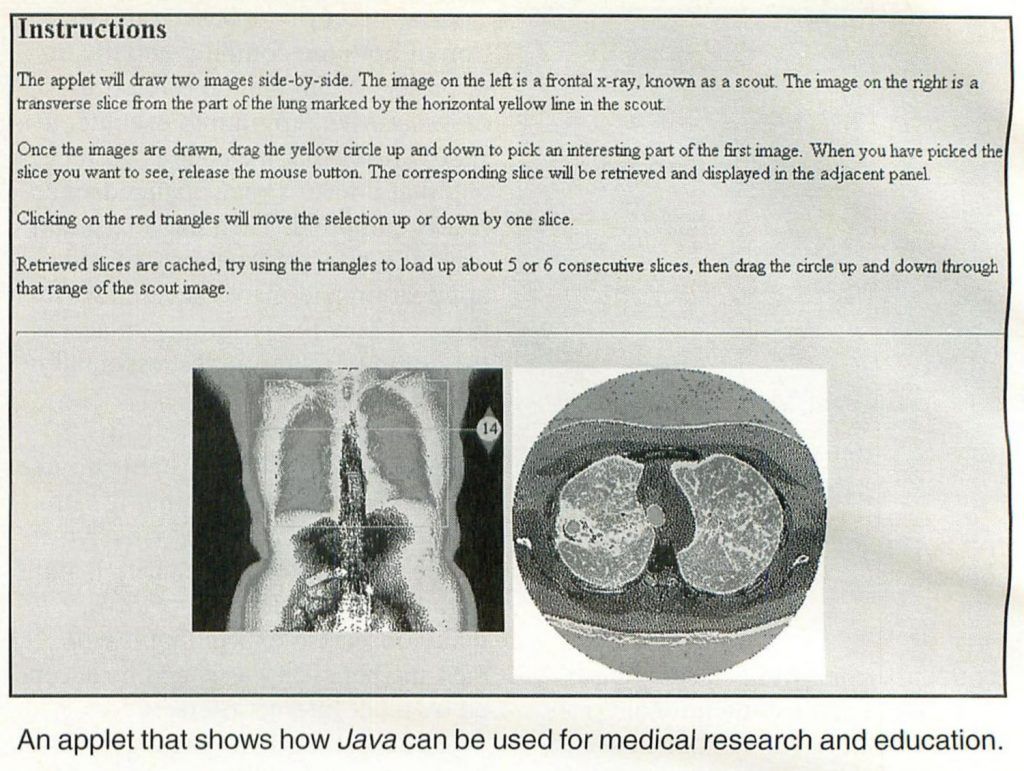

On 23 May 1995, Sun Microsystems launched a new programming language into the world: Java. As part of the launch, Netscape announced that it would license Java for use in the browser. This was all well and good, but Java didn’t really fit the bill for the web. Java is a general-purpose programming language that promised Write Once, Run Anywhere (WORA) functionality, but it was too complicated for web designers and other non-programmers to use. So Netscape decided it needed a scripting language, which was a trendy term at the time for a smaller, easier to learn programming language.

Netscape’s relationship with Sun soon influenced the scope for Brendan Eich’s project. The language he’d be developing now wouldn’t be based on Scheme; instead it would have to be somehow connected to Java. The idea was to have JavaScript and Java be the programming equivalent of Microsoft’s Visual BASIC (the easy one) and Visual C++ (the hard one).

The decision was made that JavaScript — or “Mocha” as it was originally code-named within Netscape — would “look like Java,” but be an object-based language rather than class-based like Java. Eich recalled later that “I was under marketing orders to make it look like Java but not make it too big for its britches … [it] needed to be a silly little brother language.”

Regarding the name: the key word in Eich’s quote above is “marketing.” Technically, JavaScript had little in common with Java. But in 1995, Java was the hot new programming language and so it made sense for both Netscape and Sun to exploit that popularity for promotional purposes. Eich has resented the name “JavaScript” ever since — in 2020, he tweeted that it “was a big fat marketing scam.”

In any case, the plan in 1995 was that JavaScript would be the scripting language to create client-side programs that ran inside the Netscape browser, while big brother Java would be used for developing more complex web components. Eich saw JavaScript at the time as “a ‘glue language’ for the Web designers and part time programmers who were building Web content from components such as images, plugins, and Java applets.”

Eich also wanted to make JavaScript a “very malleable” language, that could be shaped and molded by others to fit multiple paradigms. This was a crucial decision early on, given the many ways JavaScript is used today — everything from client-side scripting (the original use case), to server-side (Node.js), to mobile-focused (React), and other developments that we will get into in later posts on this site.

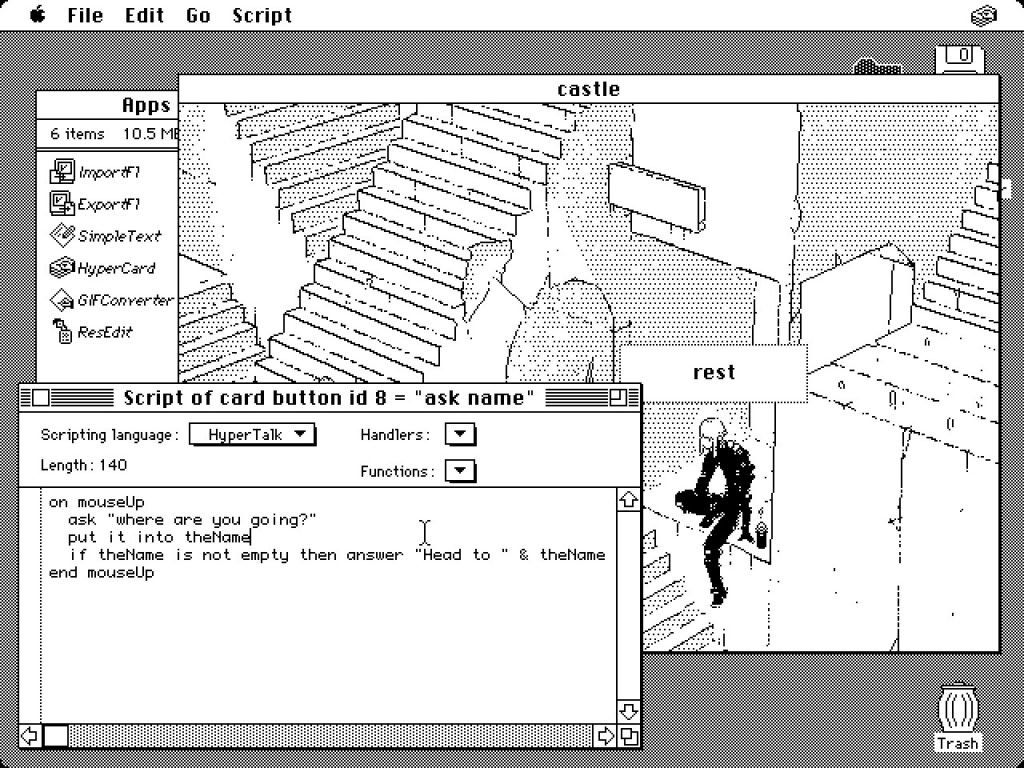

Finally, it should be pointed out that JavaScript owes a debt to Apple’s HyperCard, which pre-dated the web (I will be chronicling this product in an upcoming post). HyperCard included an object oriented scripting language called HyperTalk, that a non-programmer could easily learn. As Matthew Lasar described it in an Ars Technica feature, HyperTalk “allowed developers to insert commands like “go to” or “play sound” or “dissolve” into the components of a HyperCard array.”

HyperCard allowed users to be interactive with the program, for example by moving an object around the screen with your mouse. That type of functionality was missing from the web in its very early years. You could click on links, including links of images, but that was about as interactive as it got. Until JavaScript came along.

The format of JavaScript was in part inspired by HyperTalk, as explained in early Navigator 2 documention:

“JavaScript descends in spirit from a line of smaller, dynamically typed languages like HyperTalk and dBASE. These scripting languages offer programming tools to a much wider audience because of their easier syntax, specialized built-in functionality, and minimal requirements for object creation.”

JavaScript and Netscape Navigator 2.0

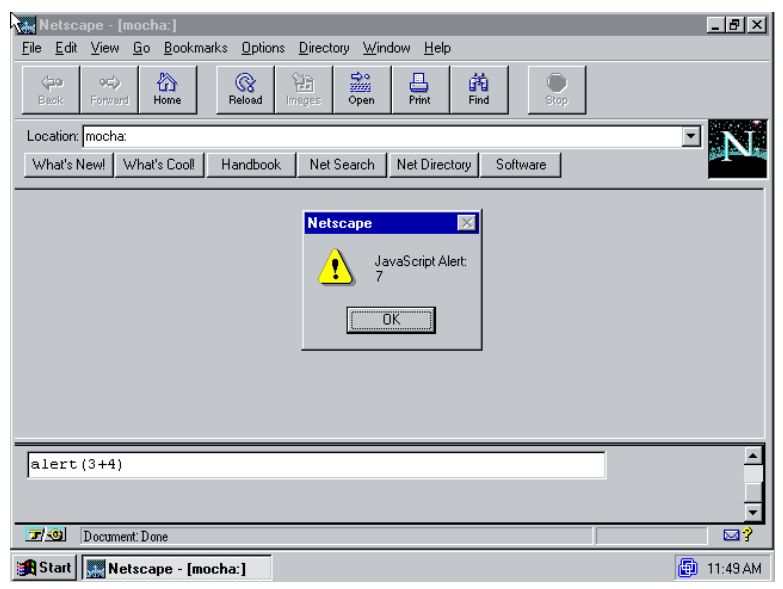

Since time was of the essence if JavaScript was to be included in Netscape Navigator 2.0, due for release in September, Eich rushed ahead and “prototyped the first Mocha implementation in ten contiguous days in May, 1995.” It was then demoed in a pre-alpha version of Navigator 2.0:

It was a hectic time for the company, in the months leading up to Netscape’s Initial Public Offering (IPO) in August 1995. But during that time, Eich focused on improving his prototype scripting language and incorporating it fully into Navigator 2.0. As told in JavaScript: The First 20 Years:

“Brendan Eich’s primary focus for the summer was to more fully integrate Mocha into the browser. This would require designing and implementing the APIs that enabled Mocha programs to interact with Web pages. At the same time he had to turn the language’s prototype implementation into shippable software and respond to early internal users’ bug reports, change suggestions, and feature requests.”

When the beta of Netscape Navigator 2 came out in September, it duly included the first version of JavaScript — although at that point it was named LiveScript. Then in early December, a press release was issued by Netscape and Sun Microsystems that officially announced JavaScript.

At the same time, the ability to process JavaScript was added to Netscape Navigator 2.0B3. Here’s how it was described in Netscape’s release notes for this beta version:

“Flexible, lightweight programmability is provided via JavaScript, a programmable API that allows cross-platform scripting of events, objects, and actions. It allows the page designer to access events such as startups, exits, and user mouse clicks. Based on the Java language, the JavaScript extends the programmatic capabilities of Netscape Navigator to a wide range of authors and is easy enough for anyone who can compose HTML.”

Initial Use Cases for JavaScript

The Netscape documentation made some suggestions in its documentation, noting that website designers could “write a JavaScript function to verify that users enter valid information into a form requesting a telephone number or zip code,” or “use JavaScript to perform an action (such as play an audio file, execute an applet, or communicate with a plug-in) in response to the user opening or exiting a page.”

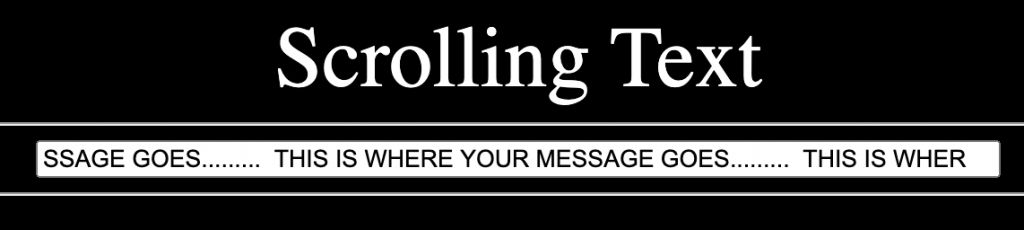

While that type of useful functionality was indeed built, it was also quickly put to use for more dubious interactive features. As Brendan Eich archly noted, early JavaScript was used for “annoyances like little scrolling messages in the status bar at the bottom of your browser or flashing images.”

There aren’t a lot of examples of JavaScript in late 1995 that are still accessible on the web, but on the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine you can view a list of basic JavaScript applications by one Michael P. Scholtis. The apps, which are dated from December 1995 to January 1996 according to the code samples, have limited — but undoubtedly cool for the time — functionality. Examples include Ticker Tape (“ticker tape scrolling text”), Rainbow (“gives the nice rainbow effect to your text”), and bgcolor Fade (“fades the bgcolor in and out on load and unload of a page”).

You can actually still see the ticker tape example in action on the Wayback Machine.

The code for this is relatively short. Never mind the technicalities of it at this point, but take note of the syntax and the fact it can be deciphered even by those of us who aren’t programmers:

<script language="JavaScript">

<!-- Hide the script from old browsers --

// Michael P. Scholtis ([email protected])

// All rights reserved. January 19, 1996

// You may use this JavaScript example as you see fit, as long as the

// information within this comment above is included in your script.

var timerID = null;

var timerRunning = false;

var id,pause=0,position=0;

function ticker() {

var i,k,msg=" THIS IS WHERE YOUR MESSAGE GOES ";

k=(75/msg.length)+1;

for(i=0;i<=k;i++) msg+=" "+msg;

document.form2.ticker.value=msg.substring(position,position+75);

if(position++==38) position=0;

id=setTimeout("ticker()",1000/10); }

function action() {

if(!pause) {

clearTimeout(id);

pause=1; }

else {

ticker();

pause=0; } }

// --End Hiding Here -->

</script>

<body onLoad="ticker()">

<form name="form2">

<input type="text" name="ticker" size="75">

</form>Conclusion

By the end of 1995, the leading web browser of the day — Netscape Navigator — had a method to add small, relatively simple, bits of interactivity onto a webpage. This would come to have great ramifications in the years to come, and eventually lead to great complexity! But for now, web designers, developers, and amateur web enthusiasts alike had a new interactive toy to play with. In the next post, we’ll explore how JavaScript was used throughout 1996.

Read next: 1995: PHP Quietly Launches as a CGI Scripts Toolset

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.