1993: Mosaic Launches and the Web is Set Free

On 14 January 1993, Marc Andreessen put a call out on the WWW-Talk mailing list for people to test a new WWW browser in development: X Mosaic.

On 14 January 1993, Marc Andreessen put a call out on the WWW-Talk mailing list for people to test a new WWW browser in development. It was initially “hypertext only,” he wrote, “but will soon have multimedia capabilities also.” He followed up on 23 January 1993 with the announcement of “alpha/beta version 0.5” of the browser, which he called X Mosaic. The X signified that it was built for the X Window System, which meant that it only worked on a few platforms — notably, not yet including Microsoft Windows or Apple Macintosh.

Andreessen, a student at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) at the University of Illinois, listed out the current capabilities of the browser, which included “document source- and URL-viewing windows” and a “hotlist capability” that was “persistent across sessions” (what we now call bookmarks). Among “future capabilities” he listed multimedia and a “3D/immersive interface.” The multimedia would come soon enough, but we’re still waiting for the 3D/immersive interface — a.k.a. the metaverse, in today’s parlance.

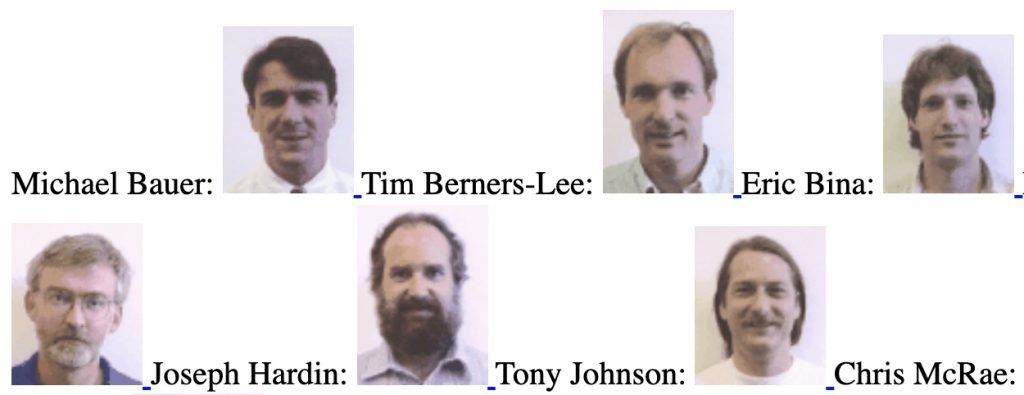

The first to reply to Andreessen’s announcement was the Web’s inventor, Tim Berners-Lee, who put copies of the X Mosaic files onto the CERN server. He praised the new browser for having “a lot of practical things which real uses [sic] want — like mail and print and a bookmarks and stuff.” He had some feature requests and bug reports, but overall seemed impressed. A follow-up message ended with this note of encouragement:

“Every new browser is sexier than the last. There is a lot of cross-fertilisation going on, which is very good. KUTGW [Keep Up The Good Work] everyone…”

Andreessen sent progress reports to WWW-Talk over the coming weeks, along with a “solicitation for widgets.” He also began adding the name of his programming partner at NCSA, Eric Bina, to the announcements.

Mosaic 1.0, Including Embedded Images

This all happened before Andreessen’s famous message in WWW-Talk dated 25 February 1993, in which he proposes a new HTML tag: IMG. With this simple message, he kickstarts the multimedia web by requesting a way to embed images inside an HTML page. Up till this point, web browsers were text-based — you could add a text link that pointed to an image file, but it would open in a separate window.

Andreessen brashly tells the mailing list that NCSA has already implemented embedded images in X Mosaic:

“This [embedded images] is required functionality for X Mosaic; we have this working, and we’ll at least be using it internally.”

It took much longer for the IMG tag to become a standard; it wasn’t included in the W3C’s HTML specification until November 1995. But note that the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) didn’t yet exist in 1993, so Andreessen probably felt he had no choice but to implement embedded images himself and wait for the IMG standard to arrive later. In many ways, he set the trend for browser companies to take the lead in web innovation. It’s almost the default now for browser companies to set standards on the Web — a consortium of browser vendors called WHATWG is in charge of the HTML standard today, which the W3C follows.

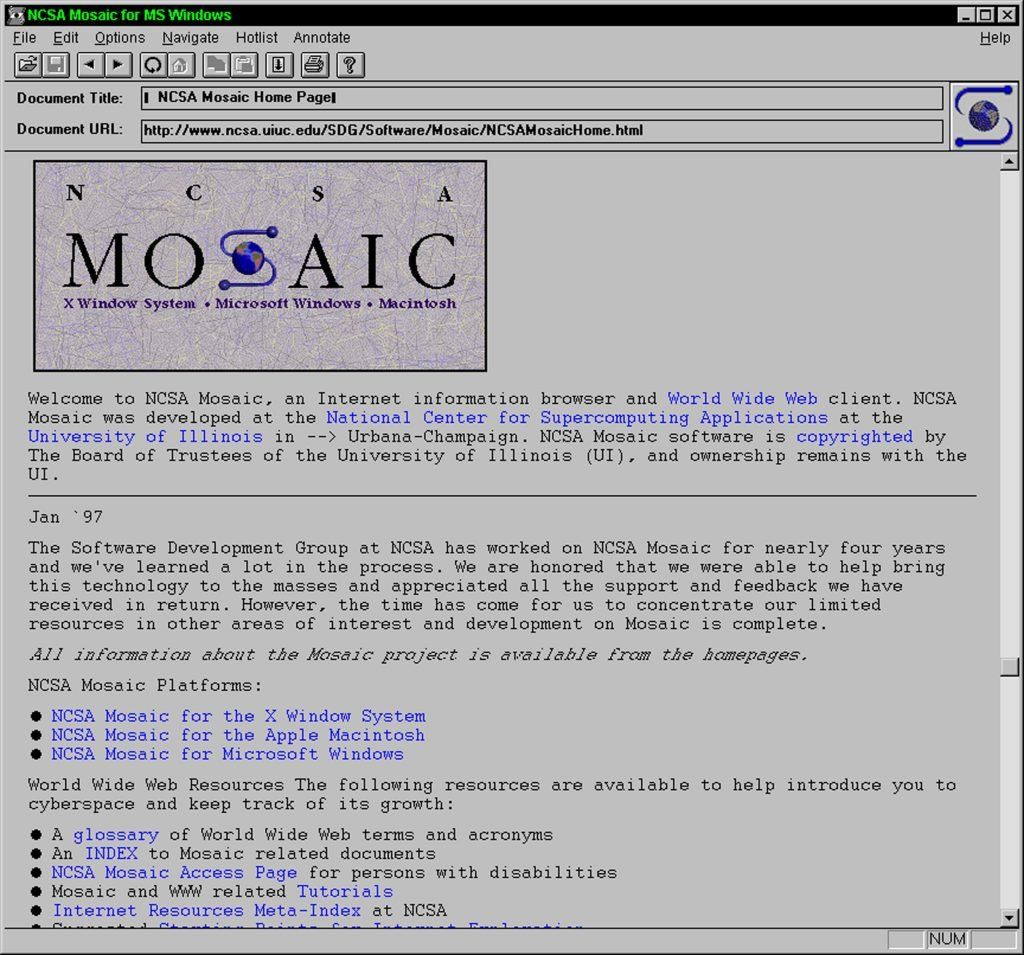

In any case, after multiple further messages on WWW-Talk, on 21 April Andreessen announced version 1.0 of NCSA Mosaic.

The very next message on the mailing list was from Berners-Lee, who was responding to someone complaining that HTML didn’t have multimedia capabilities. Not so, said Berners-Lee, pointing out that “NCSA’s (released) Mosaic for X handles embedded images in the hypertext, as does O’Reilly’s (unreleased) Viola.”

The ViolaWWW browser, as discussed in my previous post, was developed by Pei-Yuan Wei — who at this point in 1993 was getting funding from tech publisher O’Reilly & Associates. This may’ve been the time that ViolaWWW was the preferred browser at CERN, the home of the early Web. Regardless, it’s clear from the discussions on WWW-Talk that Mosaic would be a formidible new entrant to the web browser market.

The Web is Gifted to the Public Domain

Just over a week after Mosaic 1.0 was released, CERN gifted the Web to the world as open source software. As of 30 April 1993, the still relatively new Internet communications platform was suddenly free for anyone to use, with no strings attached.

The Web was put into the public domain primarily as a reaction against the owners of Gopher, the University of Minnesota, which had announced licensing fees for some users in February 1993. After user kickback, the University tried to justify its decision a month later (“How many of you are using UNIX now? It is licensed.”). Tim Berners-Lee was among many in the fledgling internet community to be deeply angered by this. In his 1999 book Weaving The Web, he called it “an act of treason in the academic community and the Internet community.” It prompted him to ask his employer, CERN, to put the WWW software into the public domain pronto. Happily, they obliged.

As Berners-Lee wrote in his book, “CERN agreed to allow anybody to use the Web protocol and code free of charge, to create a server or browser, to give it away or sell it, without any royalty or other constraint. Whew!”

Freedom was fast emerging as a keyword for the nascent World Wide Web. Just as Marc Andreessen felt free to implement an IMG tag in his Mosaic browser, Tim Berners-Lee wanted the platform he invented to be free of licences and other inhibiting factors for users.

The Tipping Point

The Web going open source was the tipping point for it to ultimately usurp competitors like Gopher, as well as commercial online service providers such as CompuServe, Prodigy and America Online (AOL). The Web had a couple of key differences to those other Internet services.

First, competing internet networks were contained and insular from a content perspective. You could only visit a select number of information resources on the likes of AOL; they were “walled gardens,” to use a term that was coined sometime in the mid-1990s.

Second, what made the Web a different beast was its potential to communicate and share information with anyone in the world. There were no geographic borders in the WWW, whereas CompuServe and AOL were US-only services. In trying to explain this expansiveness to the public, the media came up with strained geographic and space metaphors for the Web — like “information superhighway,” “global village” and “cyberspace.” They may’ve been hackneyed phrases, but the one and only internet information system they accurately described was the Web.

As 1993 went on, there was a growing excitement about the World Wide Web among its early users — admittedly, still mostly academic. In July, Tim Berners-Lee traveled to Cambridge, Massachusetts for a gathering he co-organized with Dale Dougherty from O’Reilly & Associates, called the WWWWizardsWorkshop (“W5”). As Berners-Lee noted in his book, “about twenty-five of the early Web’s developers gathered at O’Reilly’s offices in Cambridge” for the event. Andreessen and Bina from Mosaic were among them.

One of the topics of discussion was the founding of a Web consortium, which Berners-Lee had been pondering. This eventually led to the W3C being formed in 1994, which Berners-Lee would move to Cambridge, MA, to lead.

“I got a lot of things out of it,” wrote Berners-Lee in his notes from the W5 event, adding that he “was glad to see the support for a consortium.”

Non-Academic Websites Emerge

By late 1993, a handful of websites that reflected the wider culture had began to emerge on the WWW. Often they’d started out as resources on the likes of Gopher, and then made the move onto the Web. One example was the Internet Underground Music Archive (IUMA), which offered the first glimpse of the future of online music.

IUMA was started by three students at the University of California in Santa Cruz. “IUMA started with MP2 files in 1993 via Gopher, FTP, and newsgroups,” tweeted one of the founders, Jeff Patterson, in 2016. “I think the website launched in Dec ’93,” he added.

The idea was to help musicians and bands who weren’t signed by a major label. Like much of the very early Web, IUMA had an anti-establishment feel. The goal of IUMA was to create a distribution alternative to the record labels. Indie artists would send the IUMA team its music and it would be converted to a digital file and uploaded to the site.

IUMA was years ahead of its time though, because there were a couple of major obstacles the Web had to overcome before music could reliably be transmitted over it.

The first problem was the limited download speeds and bandwidth of that era. The only way to access the WWW in 1993 was by dialling into the internet on your phone line, which hadn’t been designed for high-speed multimedia.

Imagine visiting the IUMA website in December 1993. First you have to turn on your computer, double-click the ISP icon on your desktop, and click a button to “dial-up” the Internet on your modem. Whiiiiirrrrr, weeeeeeeeeee, buuuurrrrrrrrrr [white noise]… After waiting (yes, waiting!) for thirty seconds or so, you’re connected. If you are lucky, you’re able to browse the Web at 56 kbit/s — the maximum transfer speed of dial-up modems back then. More likely, you’re traveling along at 30-40 kbit/s.

You type in the IUMA link (you’ve most likely been told about it and made a note to check it out, since this is pre-Yahoo and search engines). A minute or so later the IUMA homepage slowly appears — one interminable graphic at a time — on your PC screen. You find a band to check out, say The Ugly Mugs (one of the first bands to feature on IUMA), and select a song to download. It’s a 2MB mp2 file, so to download this on a 50 kbit/s connection will take a couple of minutes. A progress bar pops up on your screen to show the download. Bit by bit the progress bar fills up, going from left to right. Finally, probably two or three minutes later, the download is complete and you can listen to the song.

This process is a long way off from the seamless streaming services we enjoy today on the web. But from late 1993 and into 1994, listening to music on IUMA was time-consuming and also could take up a decent chunk of your monthly ISP bandwidth allocation (which was maybe around 100MB, depending on how much you paid).

Mosaic is Ready For the Mainstream

The world of online music was far from the minds of the Mosaic developers, though. Marc Andreessen and Eric Bina just wanted to get working versions of their browser onto all the common platforms of the time: X Window System, Microsoft Windows and Macintosh. They achieved this by September 1993.

NCSA had also begun to publish a ‘What’s New’ web page each month, which provides a glimpse into who was coming online at the time. In October, MTV.com was online courtesy of VJ Adam Curry. In November, Mother Jones (“the national magazine of exposes and progressive politics”) had a web site. In December, Wired.com went online.

However, the Web was still very small at this point. MIT researcher Matthew Gray estimated there were 623 web pages online by the end of 1993. Most of the new web sites and servers listed on the NCSA ‘What’s New’ pages were from academic institutions. But still, the fact that the Web had even caught the interest of the likes of MTV and Wired was promising.

While web site publishing wasn’t quite ready for prime time, the World Wide Web got its first mention in The New York Times in December 1993. The main focus in the article was Mosaic, which technology reporter John Markoff described as a software program that helped “even novice computer users find their way around the global Internet.” The Web wasn’t mentioned until later in the piece. Markoff had trouble describing it (“an international system of data base “server” computers offering diverse information”), but he perceptively noted that the Web had “fundamentally changed the way information is obtained over the Internet.”

Conclusion

Clearly the Web was still very niche by the end of 1993, but it was pushing on the door of the mainstream. Early adopters in companies like MTV were experimenting with it, while curious reporters were beginning to publicize it.

Also by the end of 1993, the technical foundation was set for a truly multimedia web browser. And that foundation wasn’t just Mosaic either — CERN had done its part by gifting the World Wide Web to the world, so that anyone was now free to build on top of it.

But by releasing the web as free software, CERN had effectively signaled that it would no longer be the center of the developing web ecosystem. Heading into 1994, it was Mosaic — not CERN — that held the key to whether the web would ever go mainstream or not.

Read next: 1993: CGI Scripts and Early Server-Side Web Programming

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.