1993: CGI Scripts and Early Server-Side Web Programming

A couple of years before JavaScript was invented, a specification called the Common Gateway Interface (CGI) enabled an early form of interactivity for web pages.

A couple of years before JavaScript was invented, a specification called the Common Gateway Interface (CGI) enabled an early form of interactivity for web pages. But whereas JavaScript performed interactive tasks inside the browser (that is, on the client-side), CGI scripts ran via an external program on a server (server-side). After a CGI script was executed on a server, the result was sent back to the originating web page as HTML code. So while a CGI script wasn’t a dynamic component in the browser, like JavaScript was, it did allow early web users in 1993 and 1994 to run interactive programs. In many ways then, it was CGI — not JavaScript — that was the start of web applications.

CGI was invented in 1993 at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA), where the pioneering Mosaic web browser also originated. Rob McCool took the lead in writing the CGI specification, as a follow-on from his work creating NCSA HTTPd — one of the world’s first web servers and the direct ancestor of the open source Apache web server.

The idea was to create a common specification for the various web servers (others active in 1993 included Tim Berners-Lee’s CERN httpd and Tony Sanders’ Plexus server), so that a software program initiated via a web page could run on any server and send the result back to the web page.

The Invention of CGI

On 17 November 1993, McCool posted a message to the www-talk mailing list:

“I have spent some time writing up a formal specification for the Server-gateway interface. I invite any and all comments and suggestions. […] This is a preliminary specification of the Common Gateway Protocol, or CGP. The version defined by this spec will be CGP/1.0.”

A couple of days later, after some initial feedback from the mailing list, McCool wrote:

“I was thinking about it, and this is not really a protocol but an interface.

What do you all think about changing it to CGI/1.0?”

After a minor grumble from someone about the term “gateway,” McCool clarified that it referred to “an interface to external server programs which allow you to interface with services you may not normally have access to.”

More specifically, it referred to connecting a web server to a legacy information system — such as a database. The server that executed the CGI program was thus the “gateway” that allowed information from (for example) a database to be used on a web page. Put another way, CGI tells the web server how to pass data to and from an application.

In modern terms, we can view CGI as an Application Programming Interface (API). So in that sense, as one tutorial put it, “CGI is the API for the web server.”

By early December 1993, McCool had “written the CGI specification into a set of HTML documents, at URL http://hoohoo.ncsa.uiuc.edu/cgi/.” While that web page is long gone from the web, the Wayback Machine has a copy from April 1997. There we can see how McCool defined CGI for the world:

“The Common Gateway Interface, or CGI, is a standard for external gateway programs to interface with information servers such as HTTP servers.”

In an accompanying introduction, McCool claimed that “there really is no limit as to what you can hook up to the Web,” although he added a note of caution:

“The only thing you need to remember is that whatever your CGI program does, it should not take too long to process. Otherwise, the user will just be staring at their browser waiting for something to happen.”

Because CGI scripts were executable, they were usually placed inside a special folder. As McCool explained, this was “so that the Web server knows to execute the program rather than just display it to the browser.” This also enabled web masters to lock the folder down, to prevent people from creating potentially dangerous CGI scripts. McCool suggested the folder name cgi-bin, which soon became the norm. It became common later in the 90s to see URLs like http://www.example.com/cgi-bin/helloworld.pl.

Perl Scripts Proliferate

McCool’s specification, CGI/1.1, was soon put to use by the early users of the world wide web. Takeup was helped by the fact that developers could use any programming language to write CGI scripts. McCool listed some in his introduction:

- C/C++

- Fortran

- PERL

- TCL

- Any Unix shell

- Visual Basic

- AppleScript

In practice though, many CGI applications were written in the scripting language, Perl (this is partly why they came to be known as CGI scripts). Indeed, Perl had a big influence on the creation of CGI, as explained in this 2016 article by Michael Stevenson on opensource.com. He referenced Jim Davis’ Gateway to the U Mich Geography server, released to the WWW-talk mailing list in November 1992:

“Davis’s script, written in Perl, was a kind of proto-Web API, pulling in data from another server based on formatted user queries.”

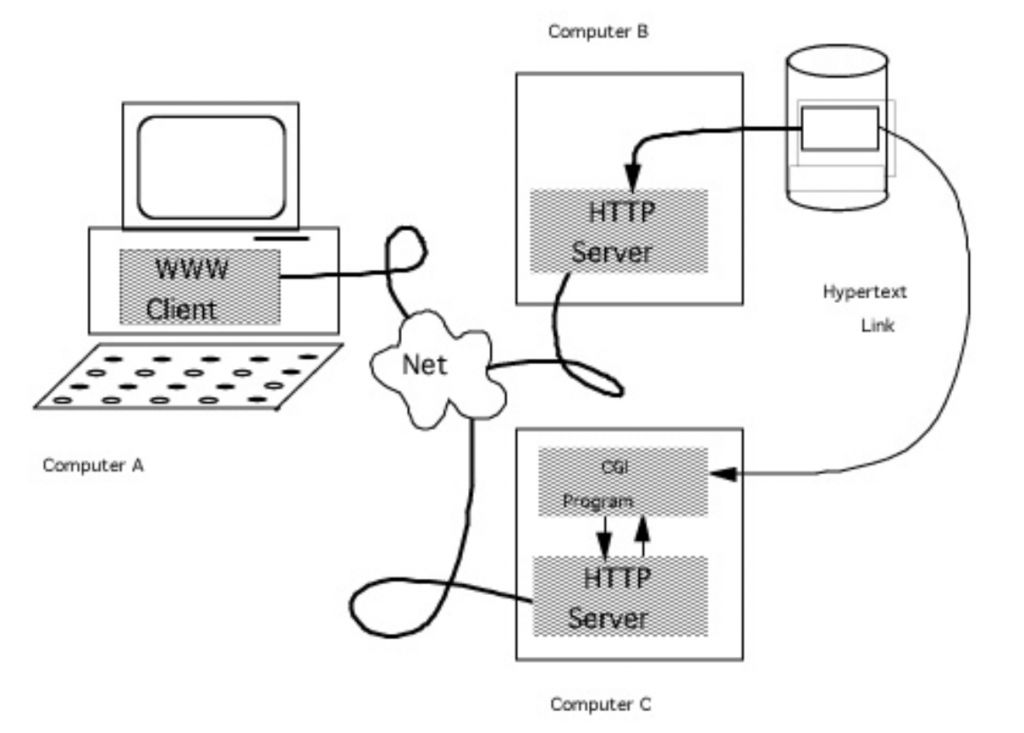

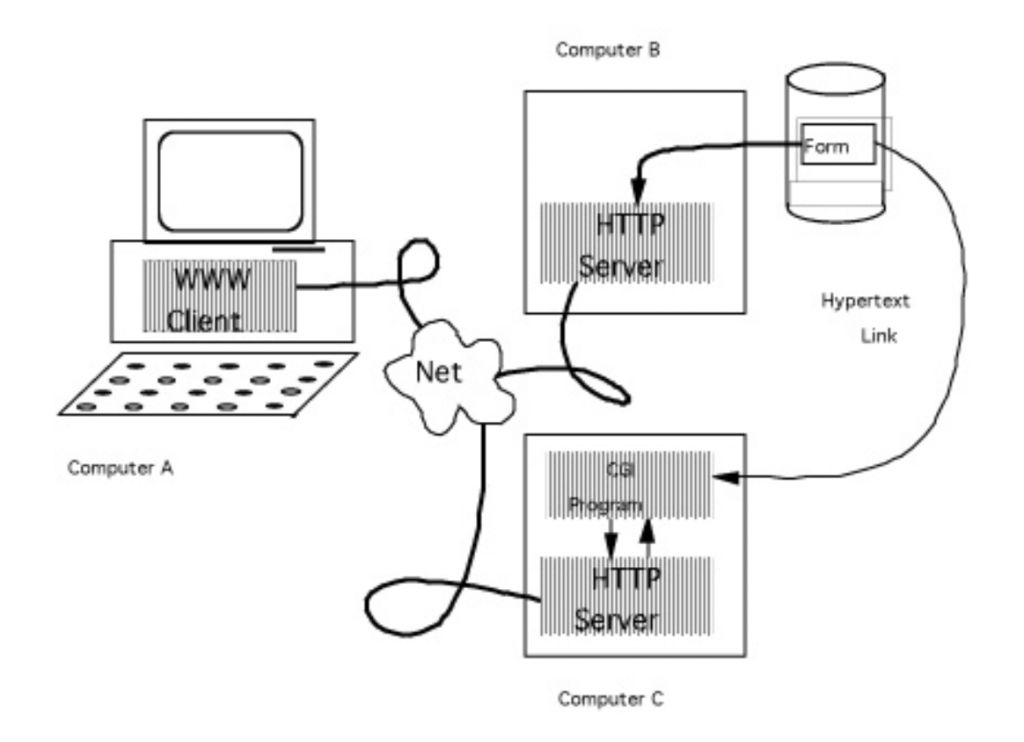

The first use cases for CGI were, unsurprisingly, focused on connecting an application to a database. So CGI was used to create things like a contact form, a guest book, a survey, or a search box. Anything that required user input, prompting a round trip from web page to database and back to the web page again, was a good candidate for CGI use.

Here’s the above diagram explained in an introductory article written sometime in 1994 at The University of Kansas:

“In this diagram, the Web client running on Computer A acquires a form from some Web server running on Computer B. It displays the form, the user enters data, and the client sends the entered information to the HTTP server running on Computer C. There, the data is handed off to a CGI program which prepares a document and sends it to the client on Computer A. The client then displays that document.”

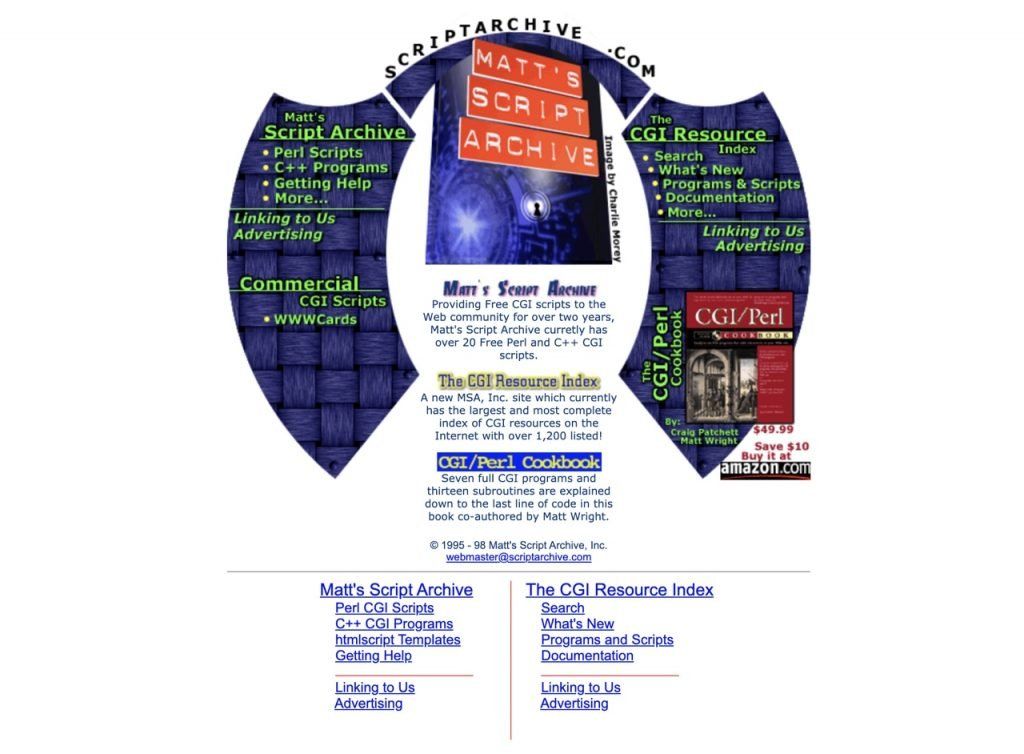

Similar to JavaScript, CGI scripts could be copied and pasted into websites by non-programmers. So if you needed a contact form, you’d search the web until you found a CGI script that enabled that. Usually it was a Perl script and over time websites like Matt’s Script Archive emerged to provide these code snippets.

Matt Wright was a high school student in Fort Collins, Colorado, when he started Matt’s Script Archive in 1995. One of his most popular scripts was a contact form called FormMail, which was written in Perl and described as “a generic HTML form to e-mail gateway that parses the results of any form and sends them to the specified users.” Unfortunately though, FormMail was inherently insecure and was soon exploited by spammers to send junk mail.

FormMail highlights a problem with CGI scripts in those early years: because by design they enabled random web users to run programs on your server, these scripts could easily be hacked if clumsily written. If thousands of other website owners then copied and pasted that same code, it would became a widespread security issue (which happened with FormMail). As a user of a computer programming forum rather bluntly put it, in a discussion about Wright’s scripts:

“…the vast majority of people downloading and implementing these scripts have no programming knowledge of their own and, as such, are ‘blissfully’ ignorant of the security risks, Y2K bugs, and the frequent total lack of proper error handling.”

Eventually, members of the Perl community started a website called Not Matt’s Scripts to provide alternatives to Wright’s increasingly popular CGI scripts. That website was last updated in 2004. Interestingly, Matt’s Script Archive lasted five more years (although it now includes security warnings).

Conclusion

One of the themes of web development in the mid-1990s, which I have explored in previous posts about Netscape and Microsoft, is the increasing complexity of web applications. The frontend (the web browser) was increasingly being connected to backend technologies, including the OS in Microsoft’s case. By 1997, Netscape was pushing a concept called “crossware” (which Marc Andreessen defined as “on-demand applications that run across networks and operating systems”), and meanwhile Microsoft was building out its Windows-integrated ActiveX technologies.

But CGI in many ways routed around this movement towards complexity, by providing an easy way to access backend functionality via a web page. The “gateway” was really just that — a virtual pipe from the browser to a server, that executed a script and then sent the result back to the browser. This simplicity enabled influential 1990s websites like Yahoo!, eBay and Craigslist to flourish, without necessarily needing to buy into either of Netscape or Microsoft’s vision for the web.

But another theme of web development is that things don’t stay still for long! 1994 saw the emergence of a new scripting language that was based on CGI: PHP, which initially stood for “Personal Home Page Tools.” Over time, PHP became a replacement for Perl CGI scripts in many cases. I’ll delve into that story in the next post in this series about server-side web development.

Lead image via researchgate.net and Wikipedia.

Read next: 1994: How Perl Became the Foundation of Yahoo

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.