1991: Tim Berners-Lee Tries to Convert the Hypertext Faithful

After a year and a half of stalling from CERN management, Tim Berners-Lee must’ve hoped the momentum he’d gathered at the end of 1990 would continue into the new year. He was sadly mistaken.

After a year and a half of stalling from CERN management, followed by a flurry of development activity over the final quarter of 1990, Tim Berners-Lee and his close colleague Robert Cailliau must’ve hoped the momentum they’d gathered at the end of 1990 would continue into the new year. They were sadly mistaken. This passage from Berners-Lee’s book, Weaving the Web, shows his growing frustration with CERN:

“As the new year unfolded, Robert and I encouraged people in the Computing and Networking division to try the system. They didn’t seem to see how it would be useful.”

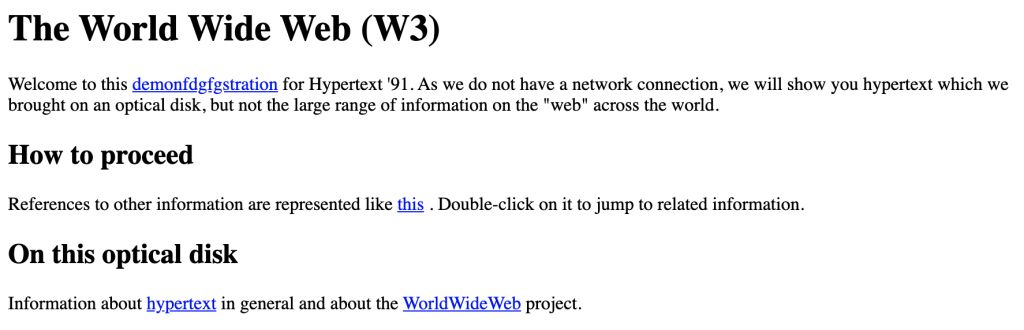

Despite the lack of interest from the rest of CERN, Berners-Lee and his small group of disciples continued to iterate on the fledgling World Wide Web. As noted in the previous post, CERN intern Nicola Pellow had begun developing a Web client for a non-NeXT platform by the end of 1990. It was a plain text ASCII browser, which they termed “line-mode,” and it was designed to even work on a Teletype machine. This was ready for testing “by spring 1991” (between March and May) according to a book published in 2000 by Cailliau and James Gillies.

Over the next eight months, wrote Berners-Lee in his book, “Robert, Nicola and I refined the basic pieces of the Web and tried to promote what we were creating.”

He eventually managed to convince one CERN staffer, Bernd Pollermann, to put the organisation’s phone book onto the Web. Pollermann, in fact, produced a new web server to connect to other computing databases at CERN.

In August, Nicola Pellow left CERN to return to college. She was replaced by Jean-Francois Groff, who did various technical and promotional tasks for the Web. In an oral history by the Computer History Museum, Groff said that his main task “was porting all the software libraries, I mean the software components that were on the NeXT system, into a universal code library that was written in C.”

The Web Goes Public

In August 1991, wrote Cailliau and Gillies in their book, “the World Wide Web was just a handful of servers, mostly in physics laboratories and none outside Europe.”

That was about to change.

On 6 August 1991, Berners-Lee announced the Web’s software to the outside world for the first time. He released the browser/editor for NeXT, the line-mode browser, and “the basic server for any machine” via the newsgroup alt.hypertext. The message ended on a hopeful note:

“The WWW project was started to allow high energy physicists to share data, news, and documentation. We are very interested in spreading the web to other areas, and having gateway servers for other data. Collaborators welcome! I’ll post a short summary as a separate article.”

The short summary he posted in a follow-up message to alt.hypertext includes an intriguing hint about the multimedia possibilities that Berners-Lee envisaged for the web:

“The WWW model gets over the frustrating incompatibilities of data format between suppliers and reader by allowing negotiation of format between a smart browser and a smart server. This should provide a basis for extension into multimedia, and allow those who share application standards to make full use of them across the web.”

Internaut Day?

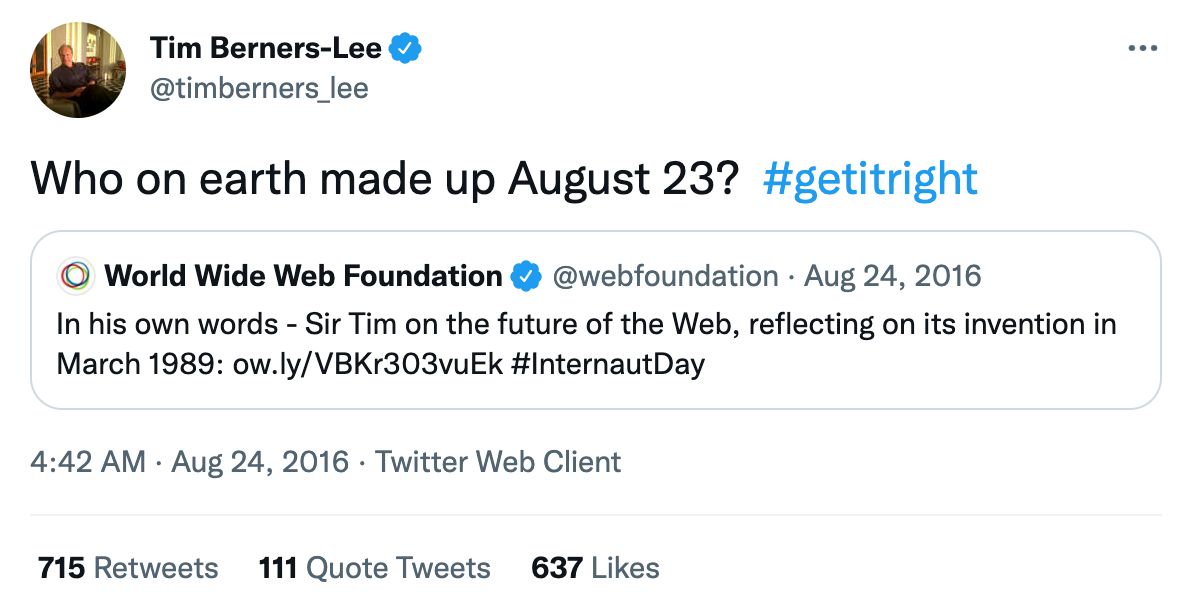

As an aside, the later plague of online misinformation even infected the history of the web. Something called “Internaut Day” was invented sometime in the 2010s and attributed to 23 August 1991. According to a 2016 article from CNET:

“On August 23, 1991, new users outside of CERN were invited to join the web, marking its official anniversry, or Internaut Day.”

The myth-busting website Snopes later debunked Internaut Day. 6 August was when users outside of CERN could access the web (a.k.a. “join the web”), so the 23 August claim made no sense. Indeed, Berners-Lee himself confirmed this in a 2016 tweet:

The First US Web Server and Hypertext ’91

After 6 August, Berners-Lee sent his web invitation to other mailing lists and interest in the Web began to pick up. People from existing hypertext and NeXT communities downloaded the software and experimented with it. Then in late October, Berners-Lee launched a mailing list focused on the web — WWW-Talk — and a small group of mainly academic people began communicating on it. For instance, Edward Vielmetti from the University of Toronto wrote on 11 November, “I’m slowly but surely converting the files on ftp.cs.toronto.edu./pub/emv to be in the WWW format.”

Vielmetti later commented on his blog that an HTML file named archie.html was “the first HTML I ever wrote; the file date is 12 Nov 1991.”

The first web server in the US went live on 12 December 1991: http://slacvm.slac.stanford.edu. It was set up by a Stanford physicist named Paul Kunz, who installed it on an IBM mainframe computer at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC).

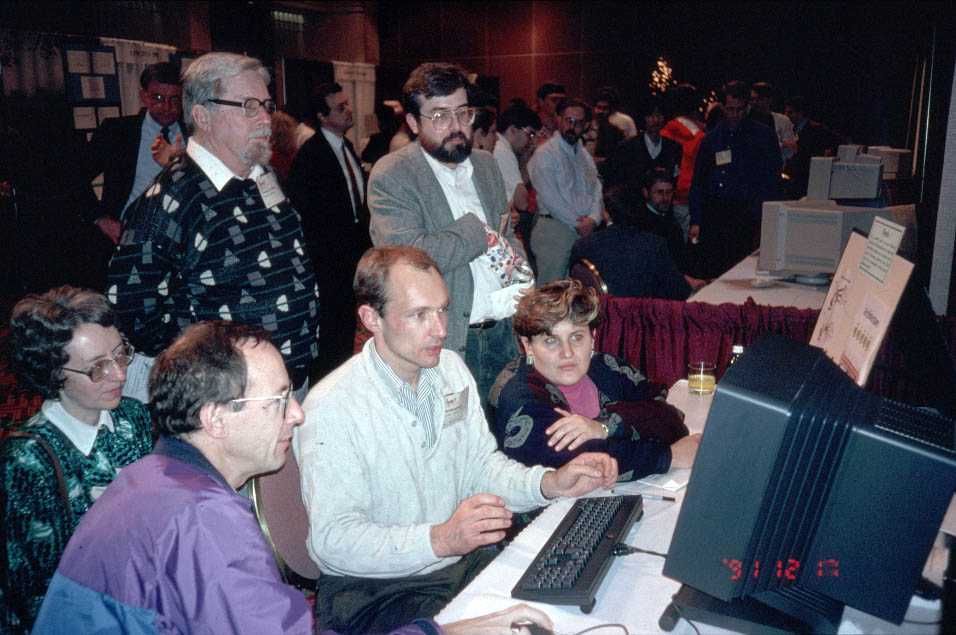

This happened just a few days before the ACM Hypertext 91 Conference kicked off, in San Antonio, Texas. Berners-Lee and Cailliau had traveled to the US for this event, hoping to promote the Web.

Incredibly, the paper that Berners-Lee and Cailliau submitted to the conference was rejected. The pair were at least able to demonstrate the World Wide Web to attendees (it’s where the feature image for this post was taken). However, it must’ve felt like deja vu, because according to Cailliau’s book, “the hypertext community was not impressed with the Web.” It was CERN indifference all over again.

It turned out the beautiful simplicity of the Web was lost on Hypertext ’91 attendees, who were only interested in the “bells and whistles” of software like HyperCard.

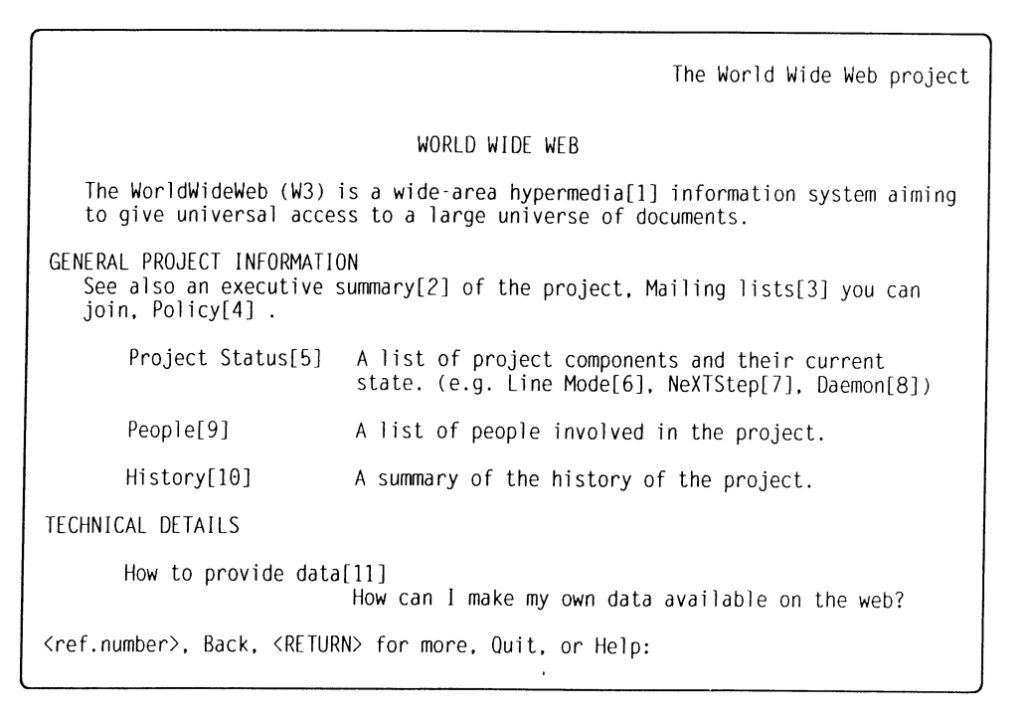

The web page that Berners-Lee demonstrated at Hypertext ’91 was thought lost until 2013, when a North Carolina professor named Paul Jones unearthed a copy of it. As noted in a BBC article about the discovery, in those days Berners-Lee “carried round a disk on which he had built a demonstration of how the web would work.” He had to use a disk because at the time, internet connections at events were hard to come by.

Jones explained that he was shown a demo of the Web on his NeXT computer at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Berners-Lee had stopped off at UNC on his way to the Hypertext conference in San Antonio. Jones continues the story:

“…he pulled out a floptical drive (NeXT pioneered a read-write optical disk in a case. No one followed). I installed Tim’s graphical browser on my NeXT. Tim talked me through using WWW by using a copy of his Hypertext 91 demonstration page. […] Tim showed me how simple and easy editing and creating a WWW page could be. First he showed how straightforward editing was by changing “demonstration” to “demonfdgfgstration.” I created my own page and added a link to an FTP site in Denmark that hosted a sound collection among other things.”

Conclusion

By the end of 1991, even despite the lack of enthusiasm from CERN staff and Hypertext ’91 attendees, the Web was beginning to blossom. As Cailliau and Gillies wrote, there were three new web browsers in the pipeline (more on that in the next post) and there were “about a dozen institutions serving up information onto the Web, including the SLAC bridgehead in the United States.”

The Web at the end of 1991 was still a tiny niche product used primarily by European academics, but it was primed to expand. The software was globally available via certain mailing lists, it was free to download and experiment with, its read/write browser application was engaging and simple to use, and the ability to click on a link to ‘jump’ to a web server across the world meant that the World Wide Web promised global access to information. All it needed was more people to test it out.

In the next post, focused on 1992, we’ll look at the first external web browsers to be released and the worldwide growth that finally began to occur for the Web.

Read next: 1992: The Web vs Gopher, and the First External Browsers

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.