1990: Programming the World Wide Web

In the final few months of 1990, Tim Berners-Lee and his colleague Robert Cailliau developed the world’s first browser, created HTML, wrote the first web server, and invented HTTP.

In the final few months of 1990, 35-year Tim Berners-Lee and his colleague Robert Cailliau developed the world’s first web client (a browser/editor), created the HyperText Markup Language (HTML), wrote the first web server, and tied it all together with an Internet communication protocol called Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP). This led to the first web page at info.cern.ch, which was live by Christmas Day, 1990.

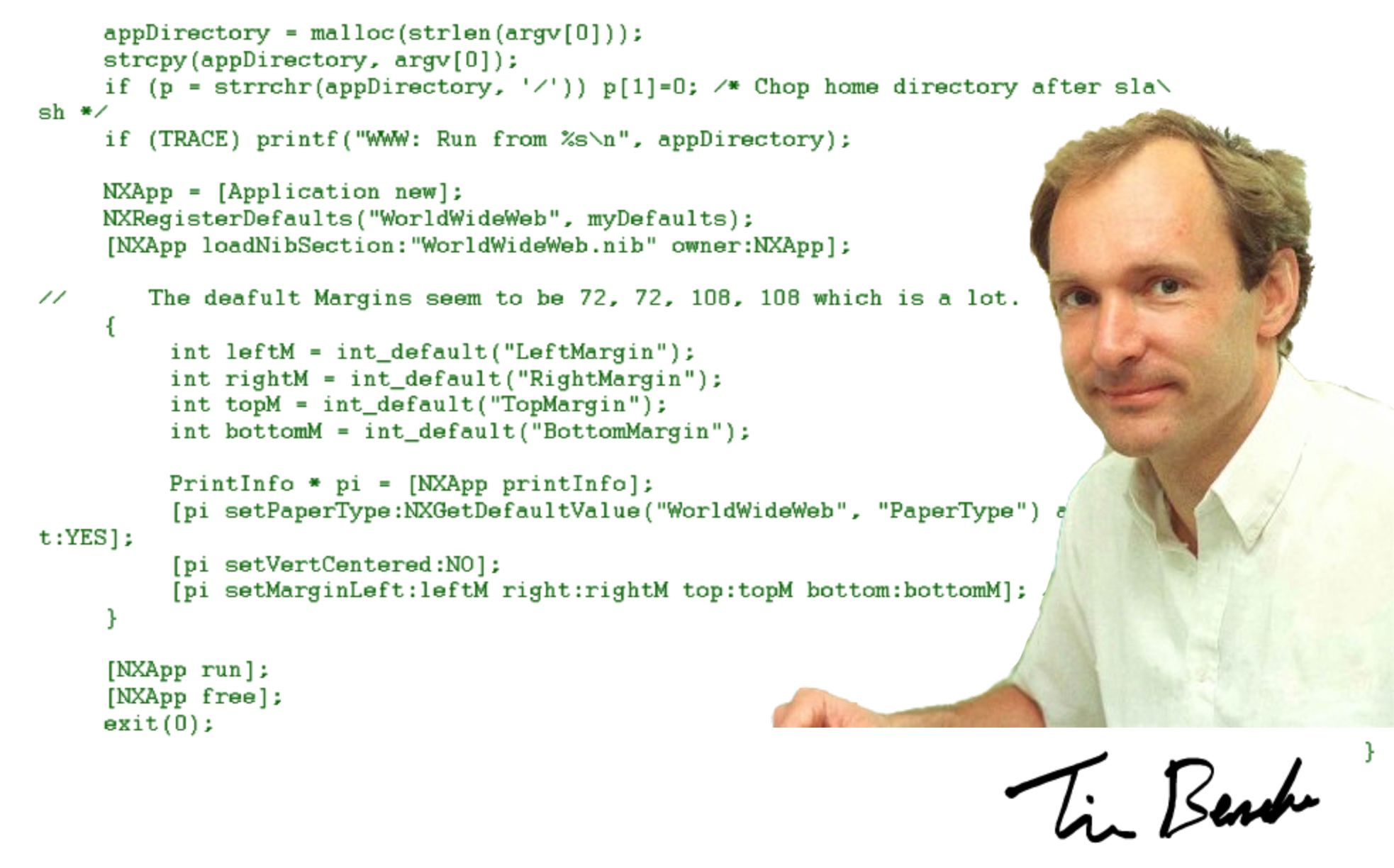

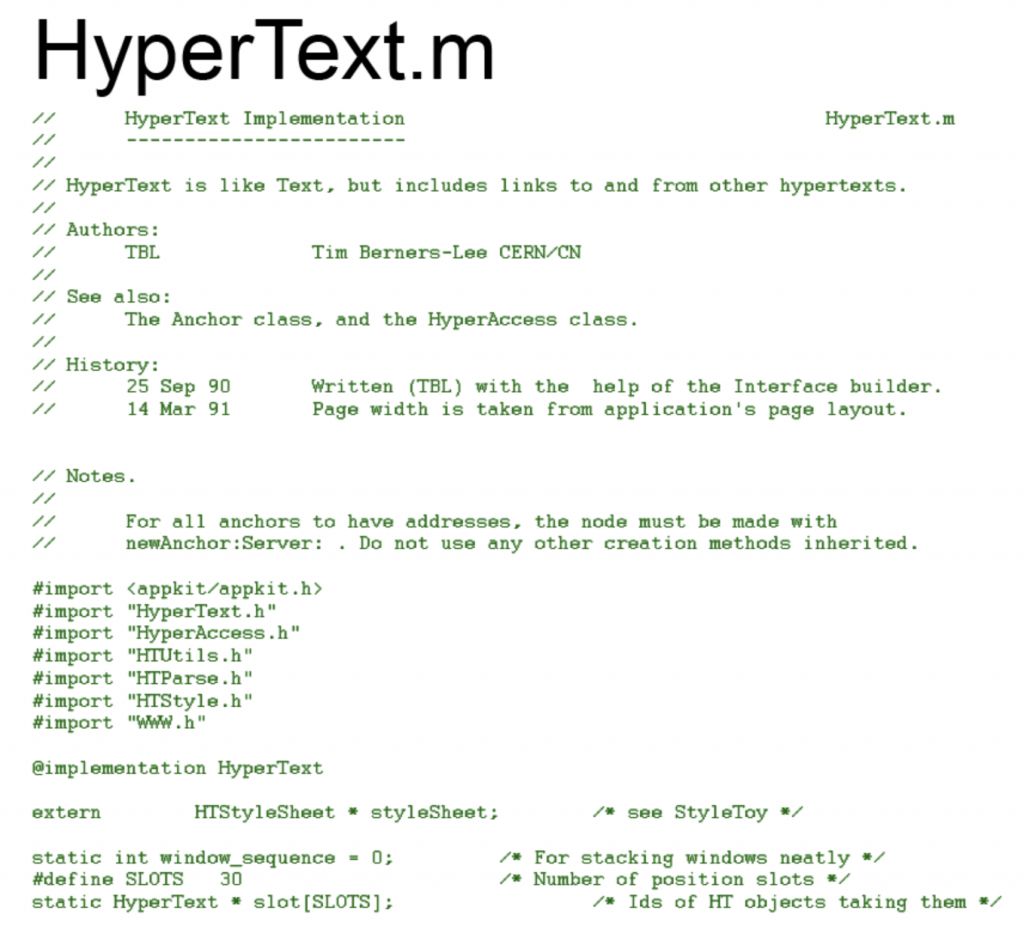

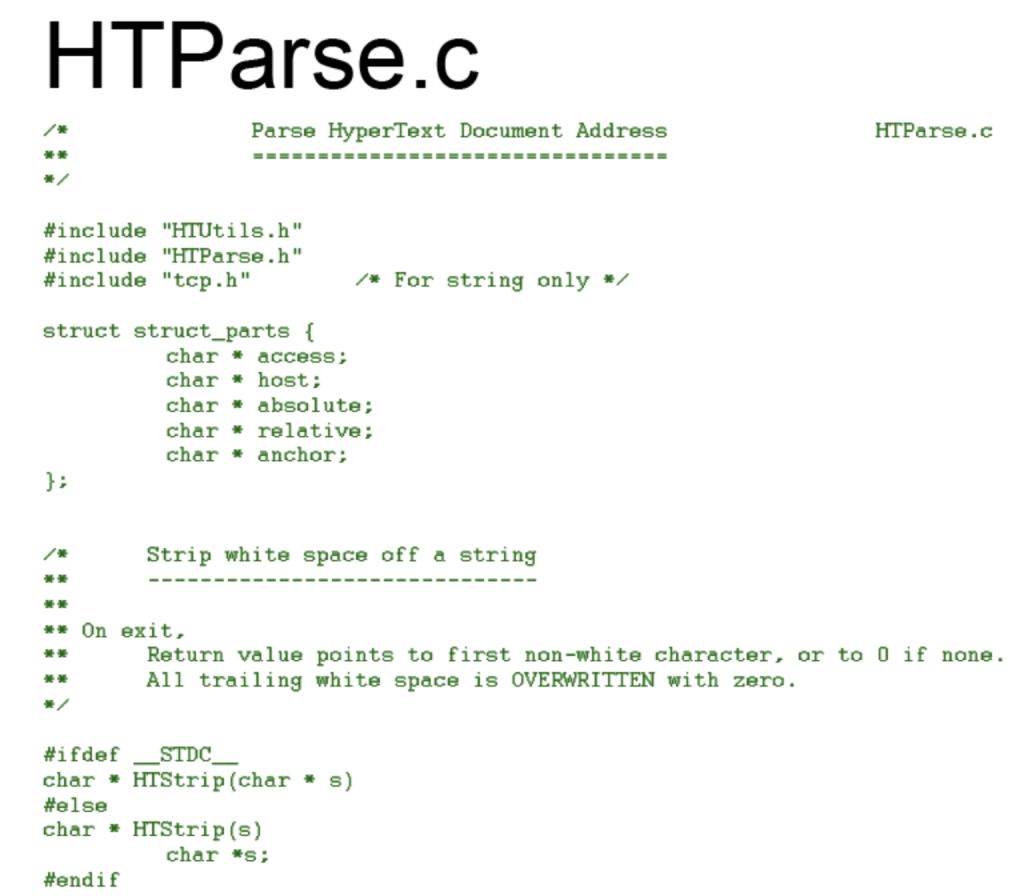

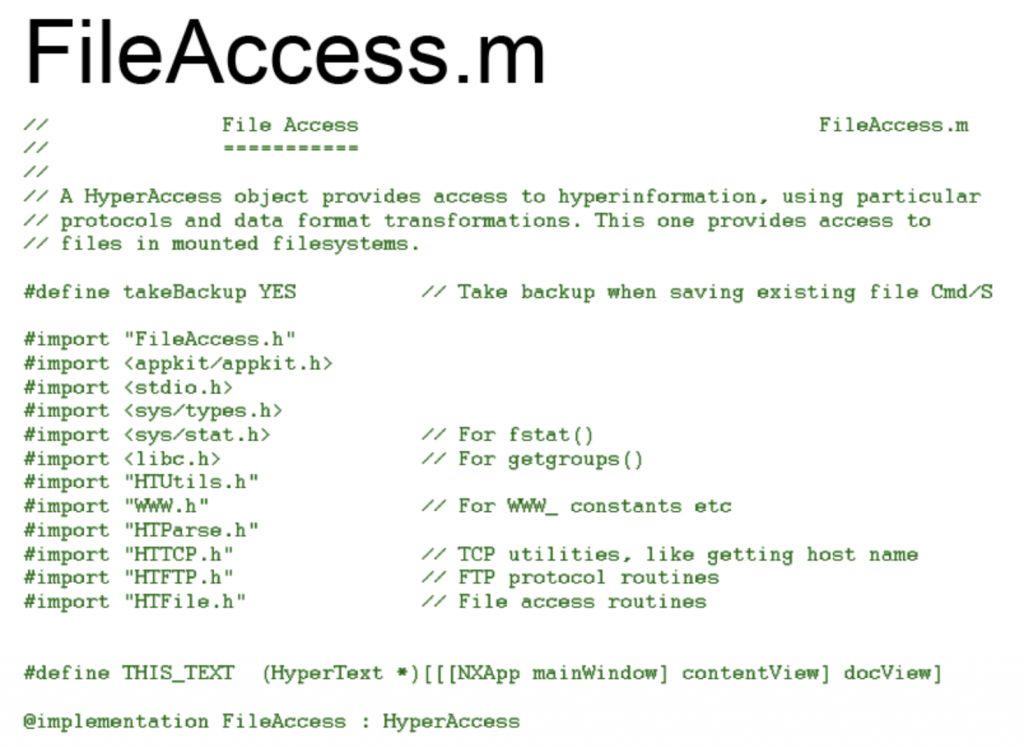

Over thirty years later, in 2021, we finally got to see some of the original source code for the World Wide Web. In June of this year, Berners-Lee put an NFT (non-fungible token) of nearly 10,000 lines of the code up for sale at Sothebys. The NFT also included a letter from Sir Tim and an animated video, but the source code was the main attraction. It eventually sold for $5.4 million at the end of June. The sale was controversial, although Berners-Lee compared the NFT to a signed poster and said that proceeds would go to initiatives he and his wife supported. Regardless of what you think of the auction, the NFT allowed us a peak at the Web’s original code and I’ll be including screenshots of it throughout this article.

The Very Beginning

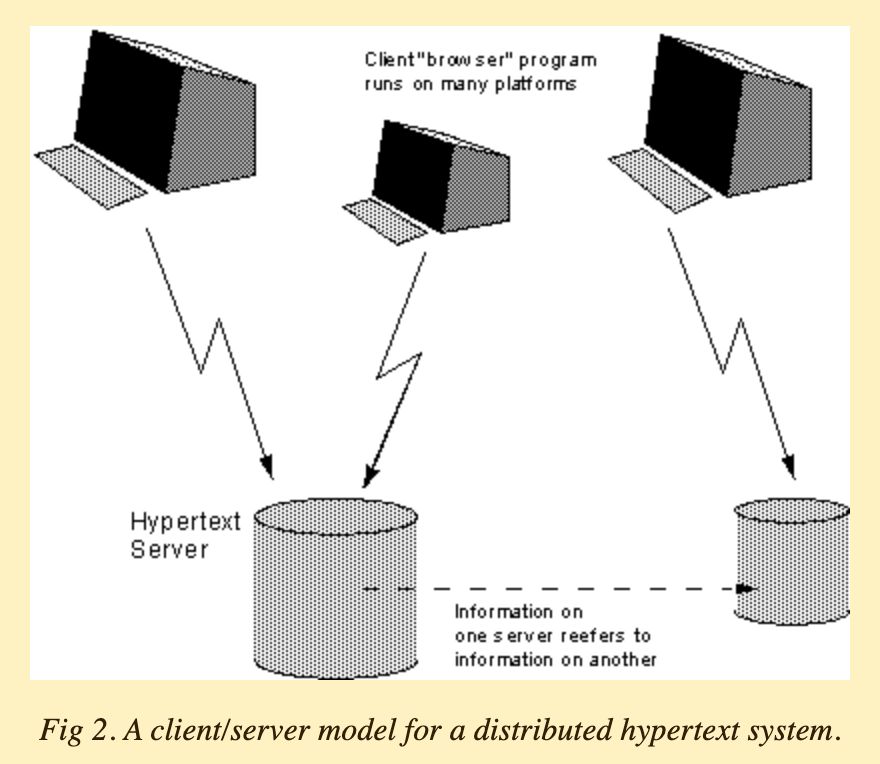

Let’s go back to March 1989, which is when Berners-Lee first proposed the idea for a global hypertext system to his bosses at CERN, a European research organization based in Switzerland. He pitched it as a way to manage “general information about accelerators and experiments at CERN.” In short, he envisioned an information management system based on distributed networking technology. At this time, he hadn’t named it the Web. But he had come up with its basic structure, as illustrated by this diagram included in the proposal:

Things would get much more complicated on the World Wide Web over the coming years, but the above diagram — as crudely drawn as it is and even including a spelling error (“reefers”) — tells you all you need to know about why Tim Berners-Lee’s hypertext system succeeded. It was a simple architecture, but it had built-in network effects that would help it grow. Chief among those was the browser/editor application, which enabled users to not just consume content for the web, but to create it. Also key was the humble hyperlink, the mechanism by which a user could “jump” from one website to another. And the web server had the potential to process interactive applications, although this wasn’t immediately evident in 1990. The point is, all of these properties were latent in the simple architecture that Tim Berners-Lee invented.

Inspirations

Isaac Newton once wrote, “if I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” It’s a scientific saying that equally applies to web development, because you’re always building on pieces that others have built before you (or in the case of modern web development, you’re finding ways to abstract away those prior pieces!). It was no different for the inventor of the Web.

Berners-Lee noted in the proposal that he was influenced by Ted Nelson’s hypertext theories from the mid-1960s. But unlike Nelson, who had a background in philosophy and sociology, Berners-Lee was technically capable of developing a hypertext system. He was the son of two computer scientists and tinkered with computers from an early age. He then earned a degree in physics, which is how he ended up at the scientific research institute CERN.

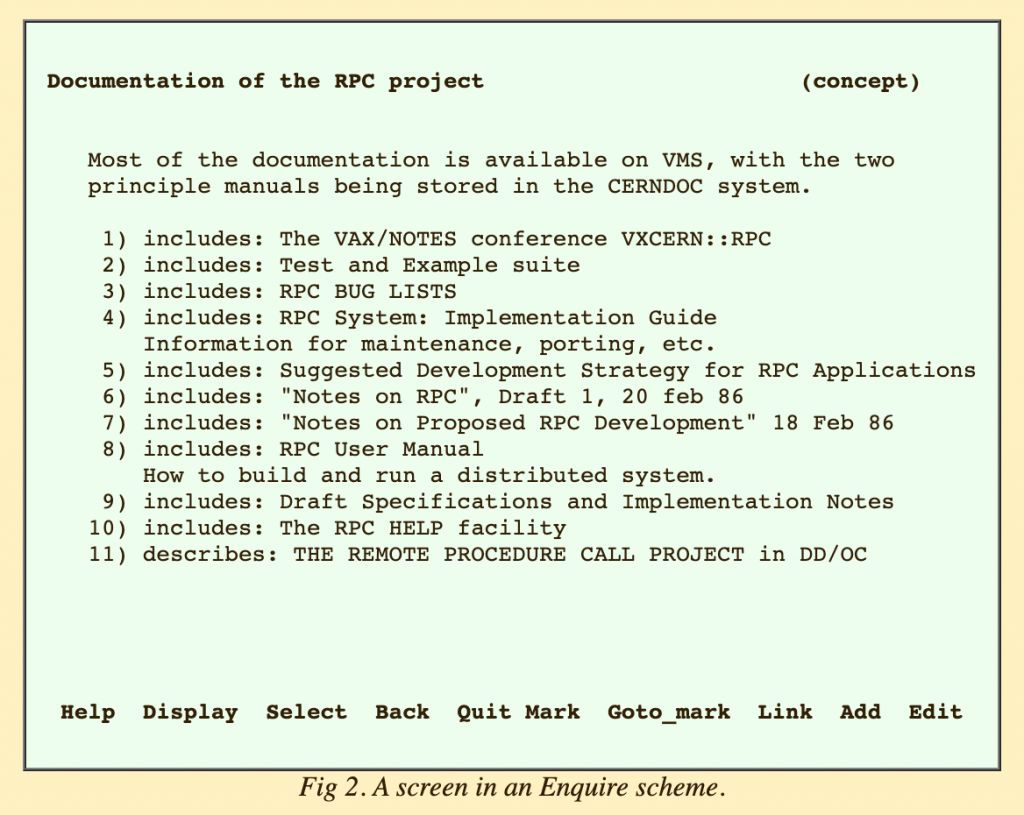

Berners-Lee had been experimenting with hypertext for at least a decade before he began coding the Web. In the proposal he referenced a piece of software he’d developed in 1980, called ‘Enquire’, which he says was conceptually similar to Apple’s later product, HyperCard (which had been released in 1987, just a couple of years before his proposal). Enquire, he wrote, “allowed one to store snippets of information, and to link related pieces together in any way.” Unlike HyperCard, he added, Enquire “ran on a multiuser system, and allowed many people to access the same data.”

The 1989 proposal makes no mention of Douglas Englebart and his late-1960s collaborative hypertext system, oN-Line System. Berners-Lee would later write in his 1999 book, Weaving the Web, that he didn’t see the Mother of All Demos video until 1994. However, sometime before that book was published, he explained on the W3C website that Engelbart was indeed an influence:

“Doug Engelbart in the 1960’s made a great system just like WWW except that it just ran on one [big] computer, as the internet hadn’t been invented yet. Lots of hypertext systems had been made which just worked on one computer, and didn’t link all the way across the world. I just had to take the hypertext idea and connect it to the TCP and DNS ideas and — ta-da! — the World Wide Web.”

Coding the Web

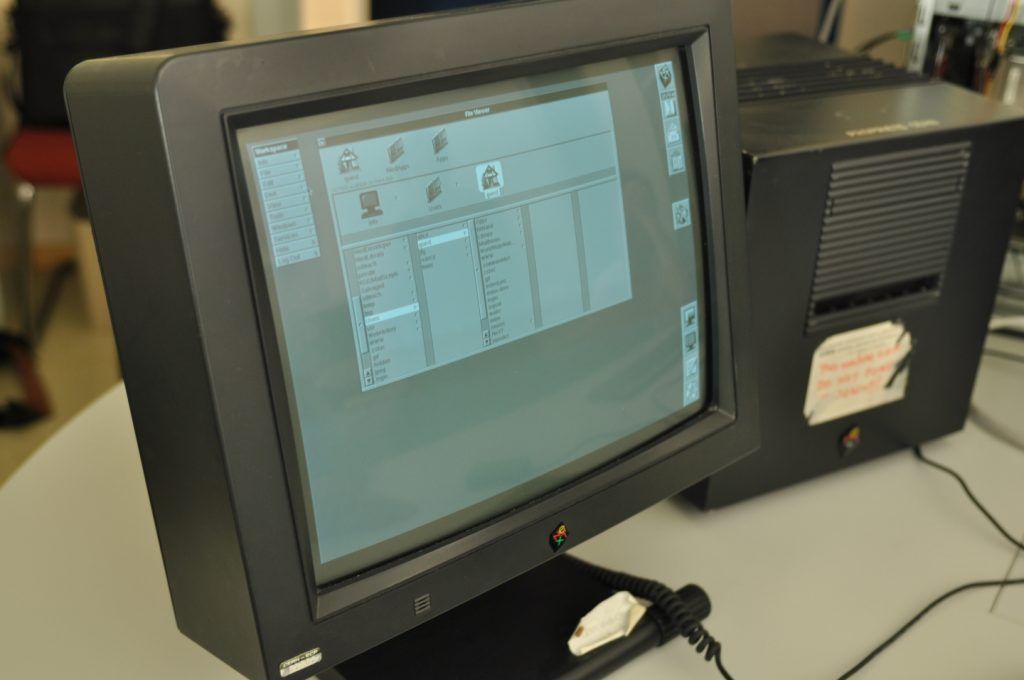

Berners-Lee’s proposal had failed to interest his bosses at CERN over 1989 and into 1990. After he’d “received no reactions,” he re-formatted the document and submitted it again in May 1990. Still no dice. So he tried another tactic: he asked his manager if he could buy a computer from Steve Jobs’ new company, NeXT. This machine, wrote Berners-Lee, “could justify my working on my long-delayed hypertext project as an experiment in using the NeXT operating system and development environment.” Years later, in the 2021 NFT, Berners-Lee would describe the NeXT as “the Harley Davidson of computers.”

This is also when he named his hypertext system: World Wide Web.

Finally, in October 1990, Berners-Lee started coding up the Web. He first focused on the Web client, which he describes in his book as “the program that would allow the creation, browsing, and editing of hypertext pages.” Essentially he was describing a word processor. He created this application — the world’s first browser — largely using the NeXT system’s visual tooling. He later described this process:

“I could do in a couple of months what would take more like a year on other platforms, because on the NeXT, a lot of it was done for me already. There was an application builder to make all the menus as quickly as you could dream them up. there were all the software parts to make a wysiwyg (what you see is what you get – in other words direct manipulation of text on screen as on the printed – or browsed page) word processor. I just had to add hypertext, (by subclassing the Text object)”

As Berners-Lee explained in his 2021 NFT letter, he only had to write code “for the things which make my app different from other apps.” The hypertext element was one of those things that couldn’t be created by drag and drop. He had to find a way to “turn text into hypertext,” which basically meant differentiating normal text from links. To code this up, he chose the programming language Object-C, “a new one for me but pretty like others I’d used.”

At the same time, he wrote the protocol for HTTP, “the language computers would use to communicate over the Internet,” and the URI document address scheme (Universal Resource Identifier). He also created HTML, the presentation language that his budding hypertext system would use.

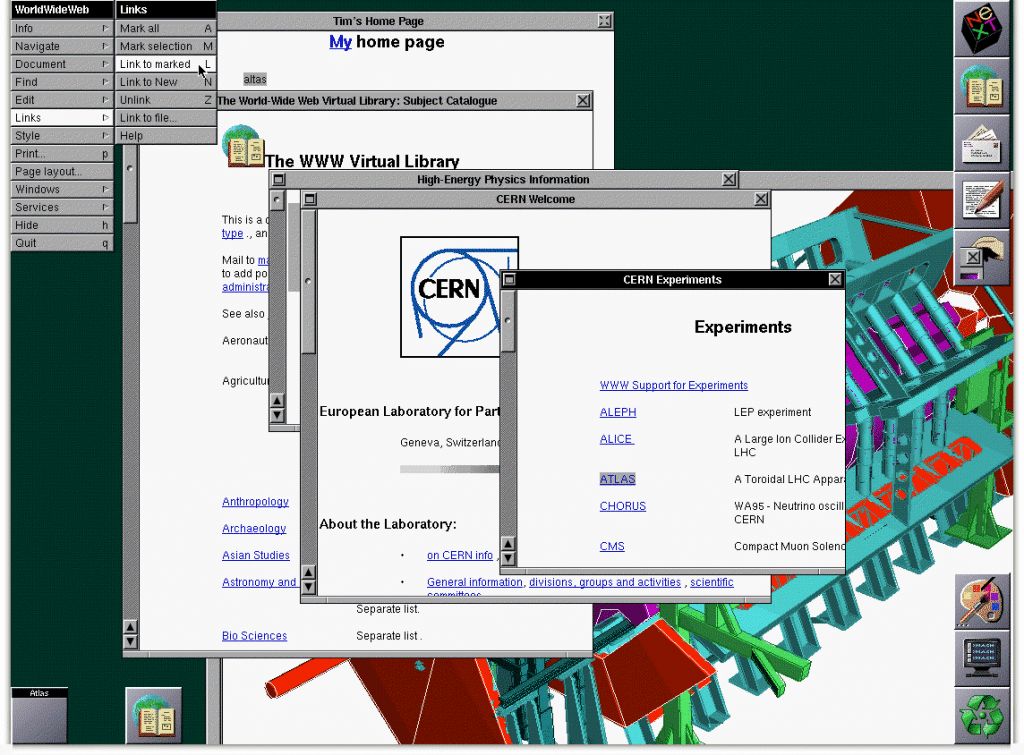

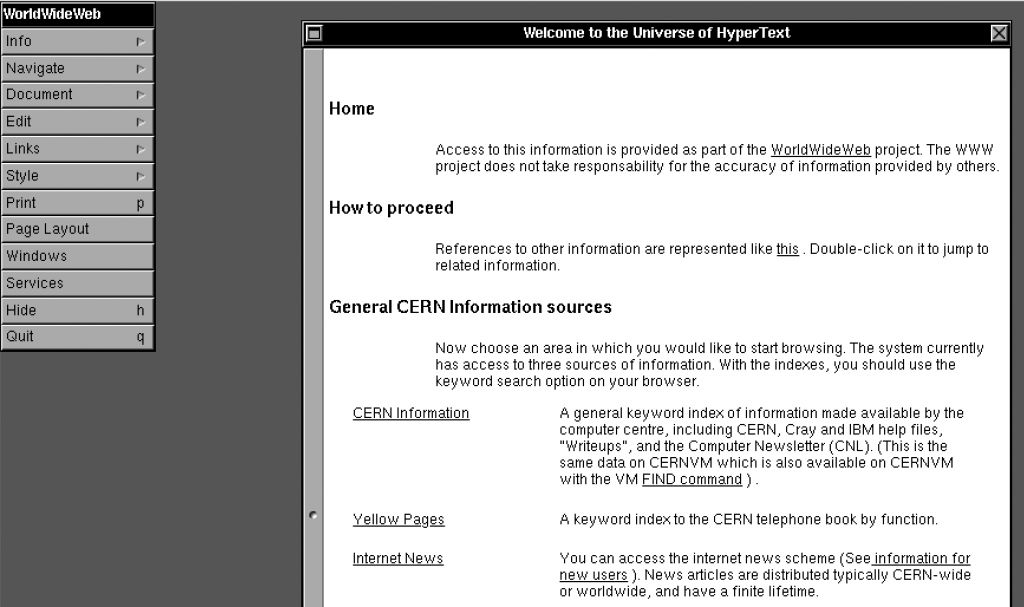

By mid-November the browser/editor was operational — he named it (somewhat confusingly) WorldWideWeb. By December this was working with HTML.

A note on how the browser got to be read/write: basically, Berners-Lee coded it so that the browser saved the web page file to your computer, and you could edit that local file. The FileAccess.m file was what enabled this. The edited document wouldn’t be uploaded back to the server, though. If you wanted to keep a copy, there was an option to choose “Save a copy offline” from the “Documents” menu of the browser.

One interesting feature of the early browser/editor was that clicking on links — including links to images, since at this point images were not embedded in the web page — would open up a new window. So by the time you finished reading a web page, you might have multiple windows open to view all the links you’d clicked. According to a 2000 book Cailliau co-wrote with fellow CERN employee James Gillies, called How the Web was Born, this feature “was designed for scientists,” as they liked to be able to refer to graphs and diagrams in a separate window while reading the accompanying text.

Over November and December, Berners-Lee wrote the first web server: “the software that holds Web pages on a portion of a computer and allows others to access them.” He registed the alias info.cern.ch, which became the first website address. Also, Berners-Lee enabled his NeXT browser to access Usenet newsgroups and FTP files, which broadened the amount of content available.

Around this time, a young CERN intern named Nicola Pellow was charged with writing a Web client for a non-NeXT platform. Berners-Lee decided the Web needed to work on “the least common denominator” platform possible, so Pellow went to work developing a plain text ASCII browser (which they termed “line-mode”). I’ll write more about this in the 1991 post, which is when this sub-project was completed.

Ultimately, Berners-Lee was reliant on the NeXT computer to get the Web up and running by the end of 1990. Cailliau had also acquired a NeXT by this time, so finally he and Berners-Lee were able to communicate with each other using the Web technology they’d built. This meant that by the end of 1990, the Web was functional — although only on the NeXT platform and Berners-Lee admitted that the HTTP server was “fairly crude.”

Conclusion

The World Wide Web, then, was created in the span of just three months at the end of 1990. Although the project was first proposed to CERN management in March 1989, it took the purchase of a Steve Jobs computer eighteen months later to actually get the project off the ground.

It’s gratifying to think that the NeXT is the missing link back to Doug Engelbart, since Jobs got many of his user interface ideas about PCs from Xerox-PARC in the 70s — which had in turn been inspired by the work Engelbart and co did for SRI in the 60s. The history of computing is full of these hypertextual-like links between people.

In the next post, focused on 1991, we’ll explore the efforts Berners-Lee and his small team made to try and get the Web adopted — both inside of CERN and out in the wider world.

Featured image: Tim Berners-Lee overlaid on his WWW code (via his 2021 NFT)

Read next: 1991: Tim Berners-Lee Tries to Convert the Hypertext Faithful

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.