The End of Web 2.0 — One Bubble Deflates, Another Starts Up

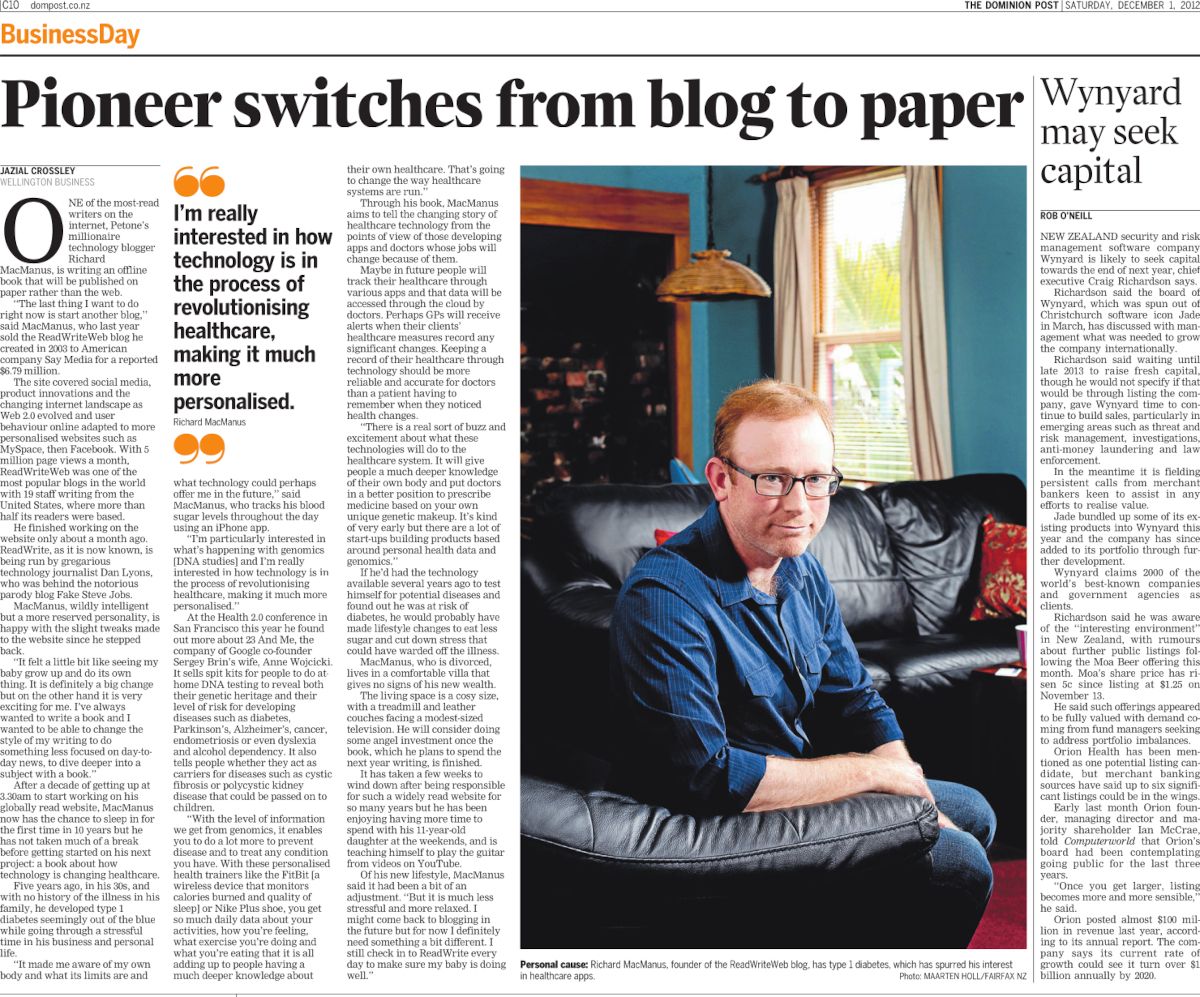

After leaving ReadWriteWeb in October 2012, it becomes apparent that the Web 2.0 era is over. I reflect on what the Web 2.0 bubble meant and how the internet industry continues to evolve.

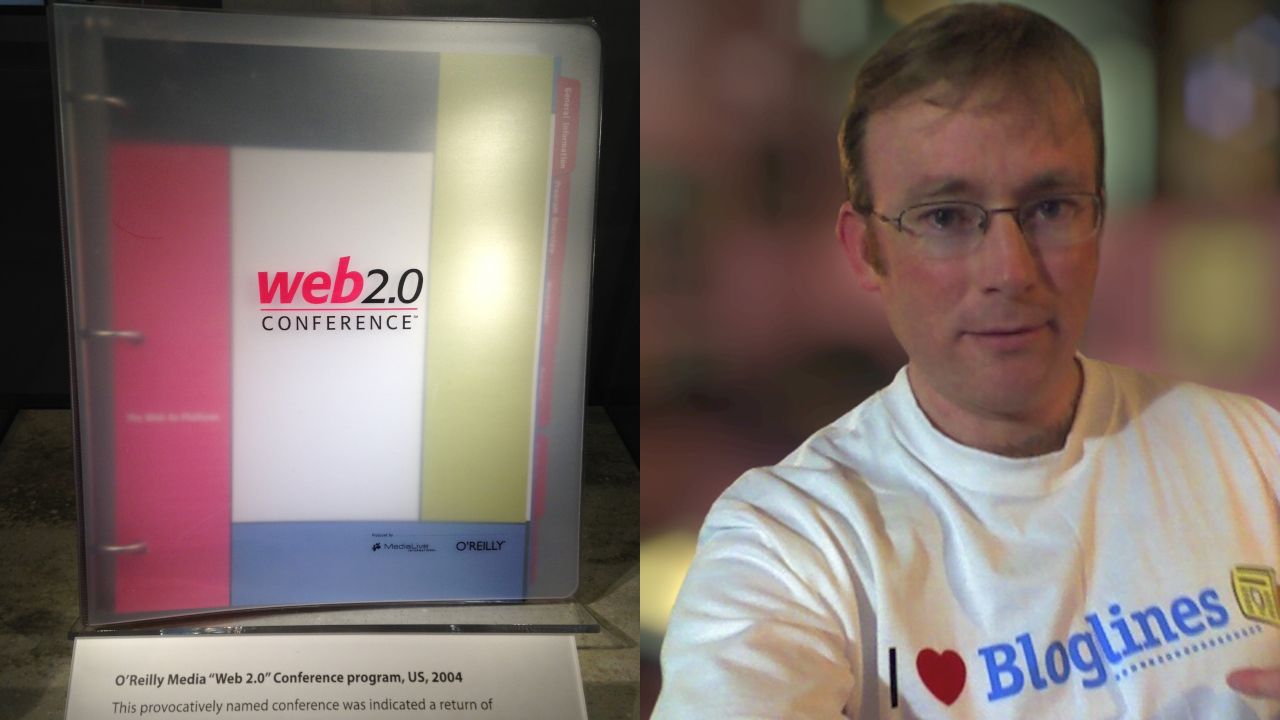

Web 2.0 was well and truly over by the time I left ReadWriteWeb. There had been no Web 2.0 conferences in 2012, and by the end of the year, even O’Reilly Media—the company that had coined the term Web 2.0—had stopped using it. It’s no coincidence that during this time, there was an expectation in the public markets that the tech bubble was about to burst.

In a December front-cover profile in Wired magazine, Tim O’Reilly was asked if there was a disconnect between the tech world and the rest of the country. “Oh, absolutely,” he replied. “I think people in Silicon Valley don’t realize what a bubble they’re living in. We saw that bubble get pricked in 2001, and it will get pricked again.”

My guess is that by not promoting Web 2.0 anymore, O’Reilly Media was frontrunning the bursting of the bubble. The Wired writer, Steven Levy, then asked Tim about his latest credo, “Create more value than you capture.”

“So many technologies start out with a burst of idealism, democratization, and opportunity, and over time they close down and become less friendly to entrepreneurship, to innovation, to new ideas,” Tim had replied. “Over time the companies that become dominant take more out of the ecosystem than they put back in.”

Of course, he was describing what Web 2.0 had turned into: an ecosystem where several large companies dominated and the dream of democratization had turned sour. Just before I left RWW, Facebook reached the one-billion-user mark in early October. But the product was also riven with privacy issues; one of my last RWW posts, dated September 30, 2012, was an analysis of “yet another privacy controversy” from Facebook, when old Wall posts from 2007 to 2009 were automatically converted into Timeline posts. The problem was that some of those old Wall posts were private in nature. Although a relatively minor controversy, especially compared to what happened to Facebook in the years to come, it was an indication that internet platforms held too much power over their users.

Developers were also starting to get screwed by Web 2.0. In September 2012, Twitter implemented restrictions on third-party use of its API. Suddenly, applications that had been built on top of Twitter’s platform—including some that had turned into businesses—were not viable anymore.

While Tim O’Reilly was busy running away from the Web 2.0 bubble, another Silicon Valley insider, Marc Andreessen, was jockeying to position himself ahead of the next bubble. Andreessen, whose Web 2.0 company Ning had been a relative failure, had started a VC firm in 2009 called Andreessen Horowitz. By the end of 2012 he was arguably the most influential VC in Silicon Valley, with investments in the likes of Facebook (where he was a board member), Airbnb, Foursquare, Pinterest, and Twitter.

“The public right now hates technology, just hates technology,” Andreessen claimed in December. “We’re in a tech depression.” He wasn’t necessarily wrong about that: Apple stock was on a downward trajectory, and Facebook was trading below its May 2012 IPO price. But Andreessen was also heavily invested in tech as a private investor, and so he was motivated to talk his book. “Airbnb is gonna eat real estate,” he said, referencing his influential essay from October 2011, “Why Software Is Eating the World.” He added that “the smartphone revolution is really hitting its stride now”—and as a board member of Facebook, he’d placed a bet on that by approving Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram in April.

Many of Andreessen’s market bets turned out to be true. The dominant companies of Web 2.0—Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft—not only entrenched their power over the 2010s, but significantly expanded it. Meanwhile, startups like Airbnb and Uber “reshaped the world,” to paraphrase the mission statement I’d helped create for the new ReadWrite in 2012.

So Andreessen was a winner from the tech bubble that emerged in the 2010s. I, on the other hand, had gotten out of the tech-blogging business before the new wave happened. ReadWrite also failed to ride the wave; the site was a shell of itself within just a year of my departure. I heard later that the domain-name change had been devastating to its all-important Google search ranking. But that didn’t explain why ReadWrite disappeared entirely from the Technorati list of popular blogs. Maybe that was because it simply wasn’t popular anymore.

SAY Media quit the blog-network business altogether in 2015, when it sold off ReadWrite along with its other properties.

As the years passed, I grew increasingly concerned about the negative impacts of smartphones and social media on our culture. By the end of the 2010s, everyone (including children) had an iPhone or Android phone, and were constantly checking the likes of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube. The web was mainstream, and internet culture had taken over the world.

Most of the successful products and platforms of the 2010s had been launched during Web 2.0, and I’d helped chronicle their rise on my blog. But in later years, it became apparent that Web 2.0 blogs like mine hadn’t written enough about the downsides of the democratization of media. I had always been a techno-optimist—no different from Tim O’Reilly and Marc Andreessen. So I’d perhaps been blinded by the shiny new consumer tools of the internet and didn’t dig deep enough into what it was doing to society, especially the impact on my daughter’s generation. She’d been born in 2001, so was part of the first generation to grow up a digital native. Looking back now, I wish I’d paid more attention to the internet’s impact on her.

The irony, at least for me, is that nowadays blogs are passé in the culture. Social media usurped blogging early in the 2010s. That was hard for me to accept, since blogging had helped define not only my career but my entire identity. As the 2020s began, I no longer knew where I fit in the tech world. I’d tried to start up a new tech blog in 2018 (about blockchain, which would later have the term Web3 foisted upon it), and I’d pivoted to email newsletters in 2019 (on Substack, a then-emerging platform in which Andreessen Horowitz invested). Neither of my projects gained traction. But that’s okay: I’ll continue to try different things as a blogger and a writer, and maybe I’ll strike it lucky again one day.

Regardless, I’ll always be nostalgic about Web 2.0 and the opportunities that blogging gave me back in the first years of the 2000s. Web 2.0 may’ve turned into a bubble over the course of that decade, and then turned darker in the following decade, but it had started out so innocently. It had been a way for me to become a creator on the web and not just a consumer, as I’d been in the dot-com era. What I created online, using blogging tools and web standards like RSS, eventually set me up for life.

Blogging also enabled me to find my community—although the camaraderie I’d felt with my fellow tech bloggers in those early years didn’t last nearly long enough. By 2005 blogging had turned into a business, and we soon became competitors instead of friends. I even lost touch with the people who had worked for me at RWW. It probably says more about me than them, but I’m not in regular contact now with any former RWWer or blog buddy from that time. Once an outsider, always an outsider.

Regardless, I’m thankful that blogging, and my role in the emergence of Web 2.0, fundamentally changed me as a person. I’d been merely half a human before I started blogging—a young man with low self-esteem who didn’t know his place in the world. Blogging was a lifeline, and I grabbed onto it. As I slowly grew my weblog into a thriving company, I also grew in self-confidence and began experiencing much more of the world around me. My online identity was developed through ReadWriteWeb, but it also helped shape—and indeed, complete—my offline identity.

The yin-yang was always more than a logo for me. I was a writer in Web 2.0, not just a reader. But that wasn’t all. I was made whole by the web. Inside, I became the man I was destined to be.

This is the final post of my book, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution. View table of contents.

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.