The ReadWrite Real-Time Web Summit, October 2009

It's a sunny fall day in 2009 and ReadWriteWeb is holding its first ever event, a one-day 'unconference' at the beautiful Computer History Museum in Mountain View, Silicon Valley.

It was the morning of October 15, 2009, and I was at the Hotel Avante in Mountain View, California, for the unconference. I was nervous and apprehensive about how the day would go—this was RWW’s first event, and the team had put in a huge amount of work. In truth, I hadn’t had to do much in terms of organizing. Chloe had taken care of operations, Bernard the costs and sponsor sales, and Marshall and Kaliya had done most of the preparation for the schedule. Elyssa had kept an eye on the project management. It hadn’t all gone smoothly: there was a lack of order in the event communications and finances that bothered me and prompted several emails to Bernard. I planned to sit down with him after the event to talk it through.

Bernard and Marshall were here at the Avante with me, as was Frederic, who had made the short trip from Portland. Dana and Jolie were already in San Francisco and would be attending the event. Our newest writer, Alex Williams, had also come down from Portland. So most of the key editorial members of the RWW team were here—the exception was Sarah, who was heavily pregnant with her first child.

Unfortunately, neither Sean Ammirati nor Alex Iskold could make it; both were busy with their own businesses. However, I’d made plans to meet up with Sean at the Web 2.0 Summit the week after. Among other things, he would be a good sounding board for the growing concerns I had about Bernard.

The team and I arrived at the Computer History Museum by shuttle at around 7:30 a.m. The day was already promising glorious sunshine, and that helped to settle my nerves as I sipped my takeaway hotel coffee and admired the view from outside. It really was a delightful venue, with a swath of green grass laid out in front of a shiny white-and-silver building. It had previously been the HQ of Silicon Graphics, a famous 1980s computer company, before being converted into the museum in 2002. So the venue felt modern and yet classic Silicon Valley at the same time.

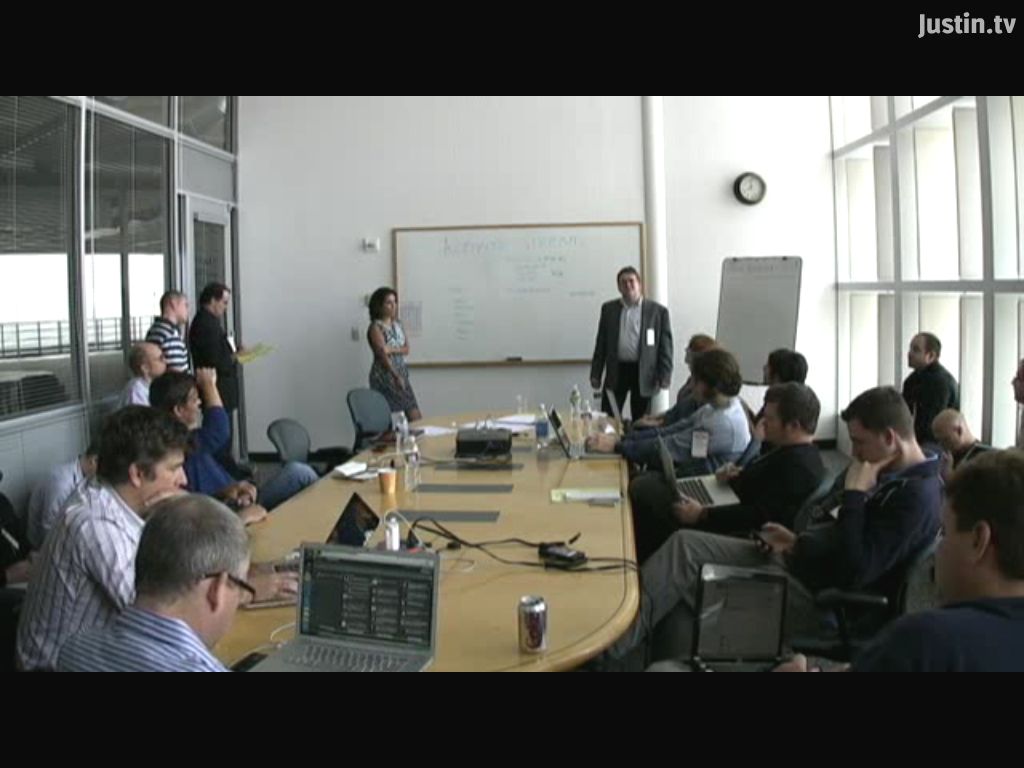

Inside the building, I inspected the check-in table and the signage in the hallway and then the setup inside the main room. It was a cavernous space, with plenty of natural light coming in through the windows. Giant silver air-conditioning ducts ran across the ceiling, which made me think of an aircraft hangar. Rows of white and black chairs were laid out in front, along with a projector and screen, and multiple round tables were dotted throughout the rest of the room. Even the tall sponsor boards looked great—very professionally designed.

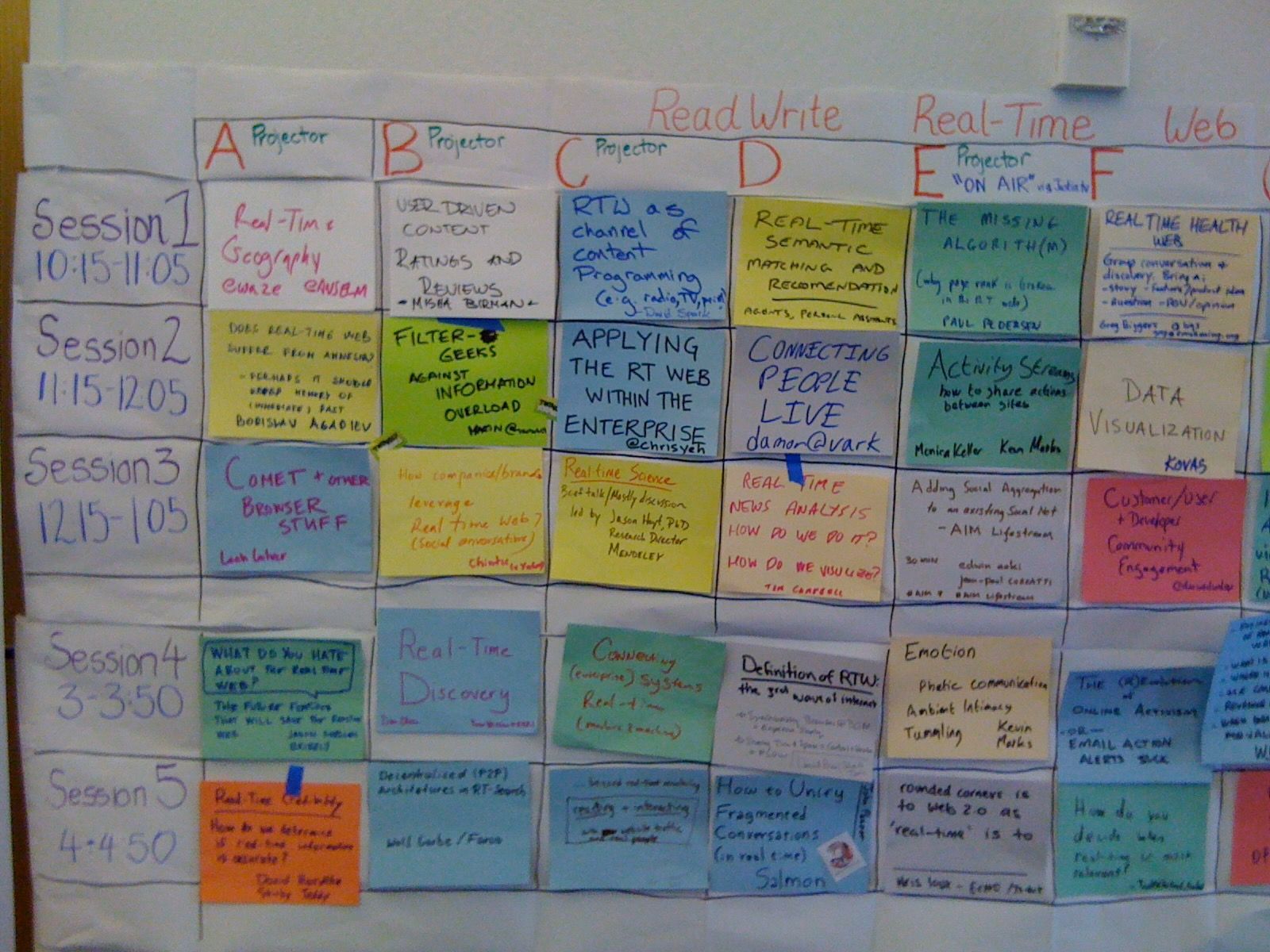

Everything looked high-tech and new except for the large pieces of white paper that had been pasted together on the front wall. But that was on purpose—the schedule would be filled in on the fly by the attendees, using red, blue, and black marker pens and colorful letter-sized pieces of paper. Kaliya and Marshall would be organizing that after my introductory speech.

Ah yes, the speech—now I was nervous all over again, so I walked back out of the main room and over to the coffee cart we’d hired for the day. Another cup of joe was unlikely to calm me, but I didn’t have any specific setup duties and so I had to do something to take my mind off the speech. Also, this gave me a chance to greet some of the attendees, who were just beginning to file in. Many of them hadn’t met me in person before, so I didn’t quite know what to say as they walked past me. But several of my blogosphere buddies also arrived—including Chris Saad and Ben Metcalfe—and they stopped to say hi and wish me luck.

When the time came to open the conference, I gulped down the last of my coffee and made my way to the front of the room. It was now filled with people—we had sold out the event and were expecting around three hundred attendees. The large room was buzzing, and it occurred to me that this was the sound of hundreds of happy RWW readers gathered under one roof. That was unusual in itself, since RWW was a completely virtual community every other day of the year. It gave me a jolt of pride to realize that the little website I’d created just over six years ago was now hosting a real-life event in the heart of Silicon Valley.

When I reached the projection unit, I turned and faced the rows of seated techies. I waited for the hubbub of conversation to settle down as I tugged nervously at my navy-blue blazer. I suddenly began panicking about how I looked, but I reassured myself that my hair was well combed and my beard meticulously trimmed. I fidgeted with my glasses as Kaliya shouted out for everyone to hush. Slowly, rows of expectant eyes trained themselves on me. Okay, then, this was it!

“Welcome, everyone, to the ReadWrite Real-Time Web Summit. I’m Richard MacManus, the founder and editor of ReadWriteWeb. This is a one-day event in which we’ll explore the technology and business of the real-time web, which has been one of the biggest and most disruptive trends of 2009.”

I’d somehow got those words out without my voice cracking too much, and I soon settled down and methodically went through my list of people to thank. I daresay it wasn’t the most charismatic speech the attendees had ever heard (many of them would’ve seen Steve Jobs in action!), but I did my awkward best. I finished up by introducing Marshall, who would give a keynote presentation about the real-time web. I also noted that we’d have a premium report coming out on this topic “in early November” (unfortunately, we’d missed the deadline to finish the report by the time of the conference). I handed the mic to Marshall and, with no small measure of relief, took a seat at the front.

Read/Write Sessions

Marshall’s presentation was the only one of the day, and it was a good primer for the topics that we hoped would define the agenda. But we weren’t in control of that—it was up to the attendees to fill in the schedule with suggested breakout groups.

To get that started, Kaliya instructed everyone to form a big circle with their chairs. At the same time, she began handing out colorful sheets of paper and marker pens.

There was a buzz of excitement in the air as everyone noisily shifted their chairs and then sat down again—or milled around in small groups—to make their suggestions. Already, this was better than silently listening to the second presenter at a traditional conference. Normally you’re struggling to suppress a yawn and craving a third cup of coffee by this point, but at our event people were moving around and chattering about their passion topics.

After fifteen or twenty minutes, Kaliya—who was stationed in the center of the circle—began calling up people to add their sessions to the agenda board. One by one, she proffered a microphone to each person carrying a filled-in piece of paper, and they explained the topic before going over to the agenda board to tape it up.

This process alone proved that the unconference format was perfectly suited to RWW and our readers. Most of the people at the event had opinions about technology—the smart, informed opinions of practicing technologists and hardworking entrepreneurs—so they had unique insights on what topics or issues were top of mind in the still emergent business of “the real-time web.” Monica Keller, who was responsible for activity streams and openness at MySpace, had an orange sheet of paper with the following words in red marker: Real time privacy / Unforgettable mistakes / Brainstorm on fix. Erik Sundelöf, cofounder of a citizen-journalism startup called AllVoices, wrote on his sheet, Real-time ranking of news/content. Jason Hoyt, the chief scientist at a website for academics called Mendeley, proposed a session about real-time science.

Within thirty minutes the entire mass of white paper was covered with giant Post-it notes like this and everyone was itching to get started with the breakout sessions. Kaliya wrapped up the agenda-setting part of the day, and we all dispersed to different parts of the main room—or to smaller designated rooms on the same floor—to participate in the first groups.

I hadn’t proposed to lead any of the sessions myself. Our job at RWW was to report on what the industry was doing and thinking, so I was mostly just curious about what the attendees wanted to discuss. Throughout the day I cruised in and out of sessions—rarely staying for an entire breakout. Partly this was just to show my face in as many sessions as possible, as the founder of the company hosting this event. But also, I wanted to take the temperature of all the discussions— which ones were full of ideas and enthusiasm, which were contentious, which were dull (there were only a couple). This would help me decide which topics were worth exploring more and potentially writing up later as RWW articles.

One of the sessions I stayed in for a while was run by Jason Shellen from Google. He’d been one of the creators of Google Reader and was running a discussion entitled “What Do We Hate About the Real Time Web.” The common theme was that users didn’t have enough control over feed consumption and other management tools for the real-time web. (Interestingly, Twitter had released a new product that very day to help with this—lists. But it was too soon to say how well lists would work or how much Twitter would promote them.)

It was noted at Jason’s session that “openness with other companies and agreed upon standards are needed.” This was a constant theme at tech conferences and meetups during the Web 2.0 era, but sadly, all too often the proposed open standards never took off. What happened with Twitter is a classic example. Despite all its talk of being an open platform in the first decade of the 2000s, Twitter’s protocol was proprietary—and was destined to remain so. One of the other sessions at our event in 2009 was run by the creators of PubSubHubbub, an open protocol for distributed publish–subscribe communication. Although Google was actively supporting it, it was never used by the likes of Twitter or Facebook. That isn’t to say that this and similar sessions didn’t eventually make their mark on the industry: years later, Mastodon would be among a new generation of decentralized social media projects to adopt the protocol.

Another big discussion point in Jason’s session was how to filter the information “firehose,” as it used to be called. What is the source authority? Who are the experts? Can we filter out boring stuff? Again, with the benefit of hindsight, we can see that such discussions didn’t lead anywhere fast. Filtering was not solved by the likes of Twitter or Facebook during the Web 2.0 era. Quite the opposite, in fact; as the 2010s unfolded, both of those companies became notorious as hotbeds of misinformation and hotheaded opinions. Still, a bunch of startups tried valiantly to solve filtering during 2009 and beyond—one of them being Jason’s latest venture, Thing Labs.

Many of the sessions were just as stimulating. By the end of the day, the RWW team was a mix of exhausted and elated with how the event had gone. As the attendees made their way out after the final wrap-up, some of them came up to me and said they had loved the summit. “It was the best event I’ve been to in years, and I mean it,” the blogger and author Violet Blue said later. She reported that she felt “completely energized” and had “so many new ideas about what I want to do next.” John Borthwick, the founder of the New York City incubator Betaworks, said “it was excellent—friggin’ great in fact.” He had brought a handful of his team members across the country for it and wished he’d brought more. These comments were a good representation of the responses we received at the Computer History Museum late that afternoon.

Of course, as CEO of RWW, I couldn’t help but wonder if we’d made a profit on the event—I was worried about this, but I’d find out the answer in the coming days. That aside, I felt like we had just made a valuable contribution to a fast-growing part of the Silicon Valley economy, the real-time web. I had a feeling that at least some of the ideas discussed at our event—not to mention the relationships forged—would lead to new web products, new protocols, or new features in existing products. So, after all the preparation and focus that had gone into the event, and despite the unknown factor of whether it was all worth it financially, I felt confident that we’d do more events of this kind.

This post is part of my serialized book, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution. View table of contents.

Next up: 043. Team RWW in Silicon Valley and a Tense Meeting With My COO

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.