Meeting My Hero, Tim Berners-Lee, at W3C Headquarters

At the end of another oversea trip in mid-2009, I visit MIT in Cambridge to meet the man who created the World Wide Web. Also, I delve deeper into the Semantic Web and Internet of Things.

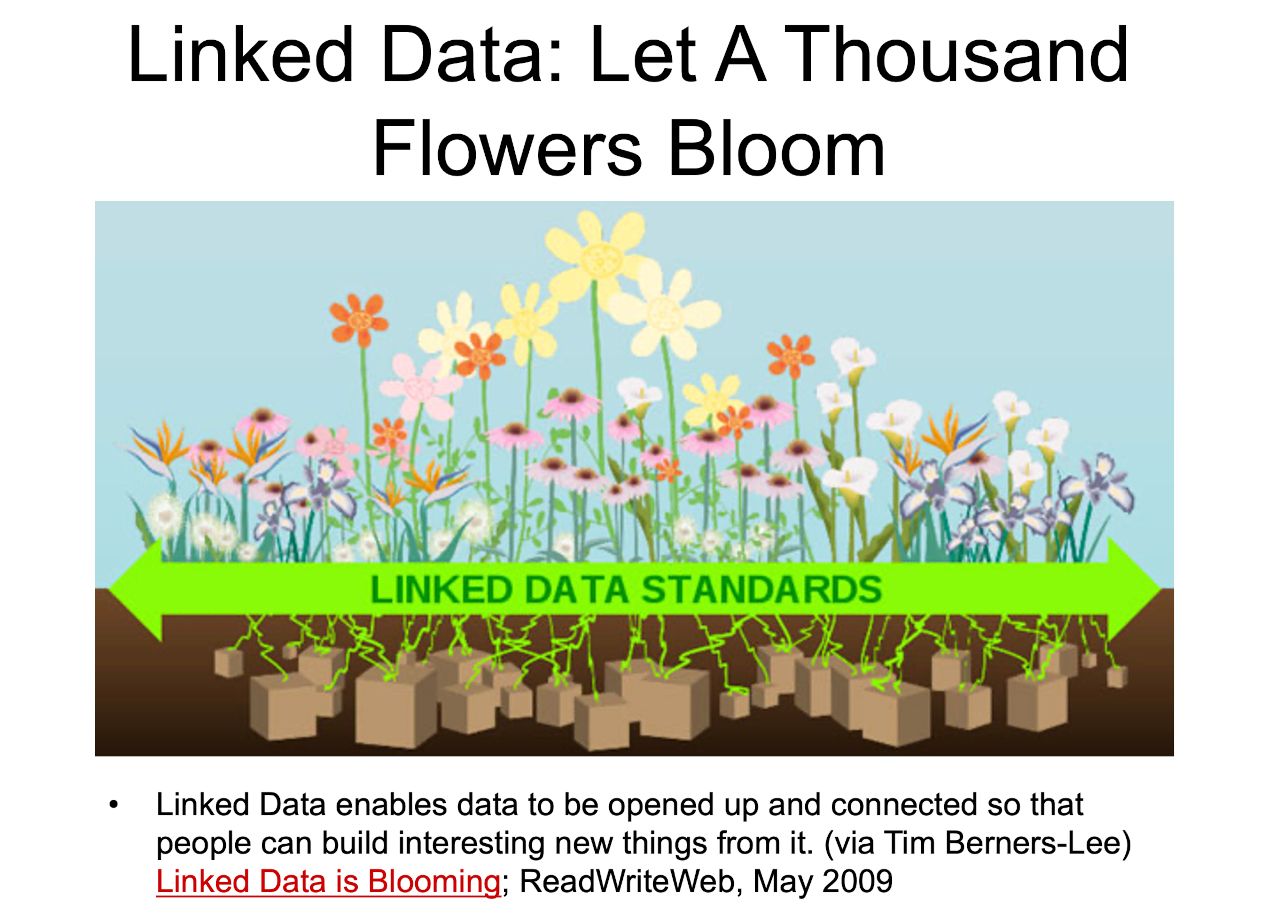

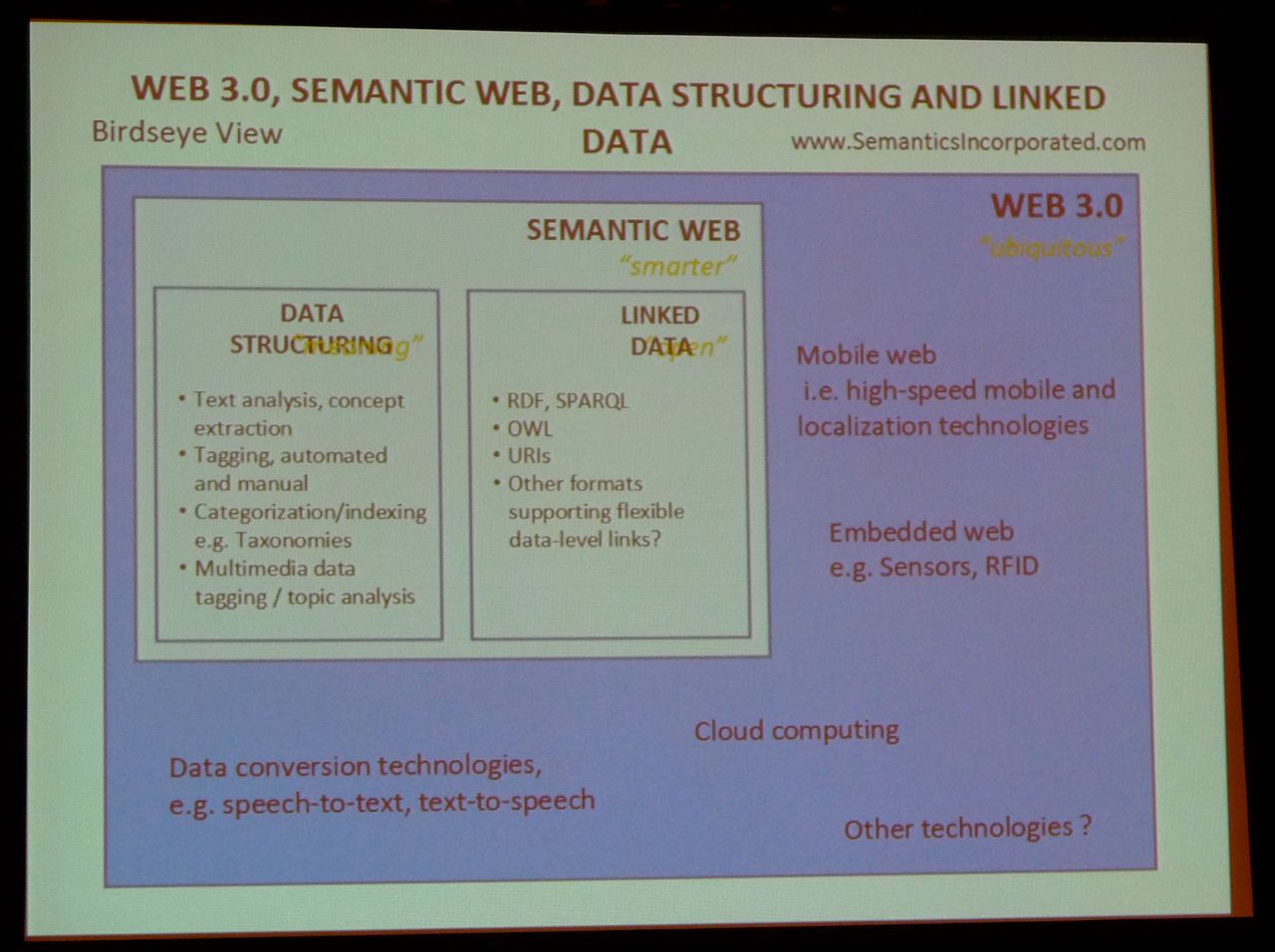

Another of my passion projects as a tech reporter was the Semantic Web (it was always capitalized at the time). In May I’d done a presentation to a Wellington tech gathering about web trends. I’d made the case that open, structured data (the so-called Semantic Web), real-time web apps such as Twitter, and “beyond the PC” things like mobile and IoT were all new or noticeably different trends in 2009.

The Semantic Web was a vision for the internet that the web’s inventor, Tim Berners-Lee, and the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) that he led were pushing hard. I thought it was an admirable goal—to make the web more structured and based on open data. This was important because despite the talk of “open platforms” by big companies, including Facebook and Google, there was a growing suspicion that they weren’t quite as open as they claimed.

In an April 2009 interview with Wired, Mark Zuckerberg used the word open nearly thirty times! The media—including RWW—was guilty of indulging Zuckerberg and other tech CEOs when they talked about openness. On the other hand, supporting open standards was a core part of RWW’s mission—the web, after all, is the ultimate open internet platform.

To provide an alternative to the version of "open" being promoted by platform companies, I thought it was important to put some focus on the W3C’s Semantic Web efforts. So I wrote several articles about it over 2009.

The middle of the year brought another overseas trip. First, I went to a Semantic Web conference in San Jose, SemTech. Next was Lift, a conference in Marseille, France, that focused on IoT, augmented reality, and other “hands-on” internet technologies. On the way back from Europe, I stopped over in Boston. I had always wanted to visit MIT in Cambridge, so I scheduled a bunch of interviews there. The one I was most looking forward to was with Tim Berners-Lee—and specifically, I wanted to talk to him about the Semantic Web.

A Visit to MIT in Cambridge

Tim’s assistant, Amy van der Hiel, had emailed me his office location beforehand: 32 Vassar Street, at the corner of Vassar and Main Streets in Cambridge. “We’re in the big, crooked Frank Gehry building—you can’t miss it.”

As I approached the Stata Center on the day of our meeting, I saw a set of buildings that looked like a mashup of 1930s futurism and modern commercialism. It was a hodgepodge of brick, mirror-surface steel, brushed aluminum, and corrugated metal. One of the buildings, which looked like an upside-down bucket, was painted bright yellow. Several others jutted out at odd angles. Windows protruded like eyes on stalks. The complex had opened just over five years earlier, and it must’ve felt like a UFO landing in the middle of Cambridge.

For all the strangeness of the Stata Center, I warmed to it immediately. It seemed like a real-world mirror of what the web was at this time: lots of jagged edges and shiny silver futurism; a sense that the structure wasn’t entirely stable, but with sections of redbrick solidity. I knew the web still seemed alien to many people, just like these headquarters of the W3C, but the growing success of technologies like blogs, Facebook, and Twitter proved that it was here to stay.

As instructed, I entered the Gates Tower (named after the Microsoft founder) and took the elevator to the fifth floor. Amy came out to greet me and quickly ushered me into Tim’s office. Before I knew it, I was shaking hands with the inventor of the World Wide Web.

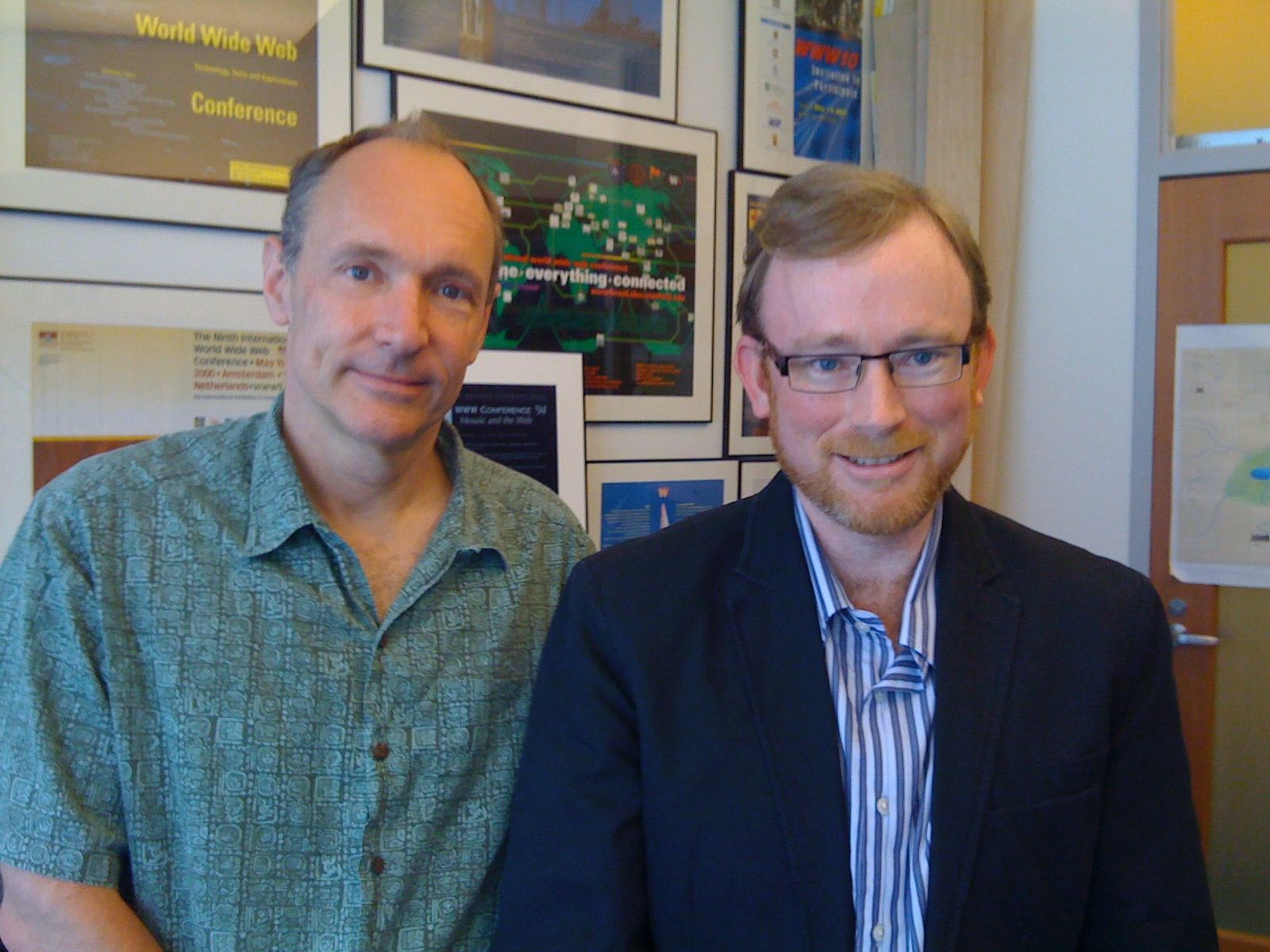

Tim, who had turned fifty-four earlier that month, was wearing a teal-green short-sleeved shirt and light blue slacks. He was a bundle of nervous energy with a receding hairline. His apparently habitual twitchiness came through in his speech; he stuttered slightly, and words flowed out of his mouth a little too quickly. Despite his nervy demeanor, he was relaxed and friendly. He politely invited me to sit down and only followed suit when I did.

Tim peered at me with what, at first, I took to be an innate curiosity. This, I guessed, was a big part of why he was a celebrated inventor. He looked and acted like a normal middle-aged man, and yet this was someone who had invented one of the most important mass--communication mediums in history.

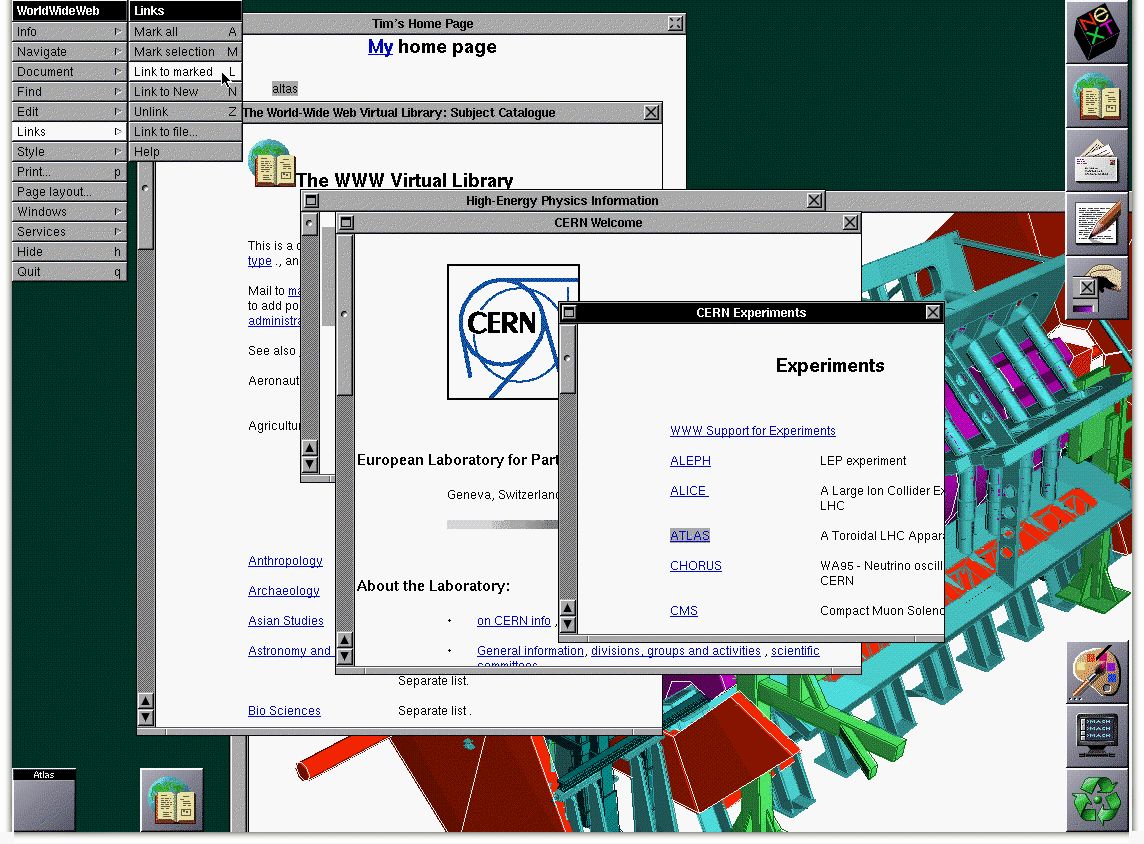

Then it occurred to me that he was looking at me expectantly, waiting for me to start the interview. I cleared my throat and told him that my blog’s name was inspired by the first browser, which he had developed in the early nineties and called (rather confusingly) WorldWideWeb. It was a read/write browser, meaning you could not only browse and read content, but also create and edit it. The web browser that popularized the web a few years later—Marc Andreessen’s Mosaic—was read-only; it had only half the functionality of Tim’s original browser. Anyway, I told Tim—and I was stuttering myself by this point—that his read/write philosophy had been a huge inspiration to me.

We then got down to business with the interview. He talked at length about the topics he was passionate about—the Semantic Web and something called “Linked Data” (a subset of the former). My main goal was to connect these rather academic topics to the wider tech industry, so I asked about search engines, e-commerce, and a new natural-language processing engine called Wolfram|Alpha, which had been released the month prior. He diligently steered all my questions back to his vision for the Semantic Web, but (in retrospect) I can see that he was also very prescient about the future of internet technology. Wolfram|Alpha would later be seen an early precursor to the AI chatbot that now dominates the internet, ChatGPT. This was almost impossible to envisage back in 2009, yet Tim clearly understood that conversational interfaces would be key in the future.

“It’s possible that as compute power goes up, we’ll see a proliferation of machines capable of doing voice,” he told me. “It’ll move from the mainframe to being able to run on a laptop or your phone. As that happens, we’ll get actual voice recognition and pattern natural language at the front end. That will perhaps be an important part of the Semantic Web.” While the Semantic Web itself never took off, he was exactly right about the increasing power of what came to be called “machine learning.”

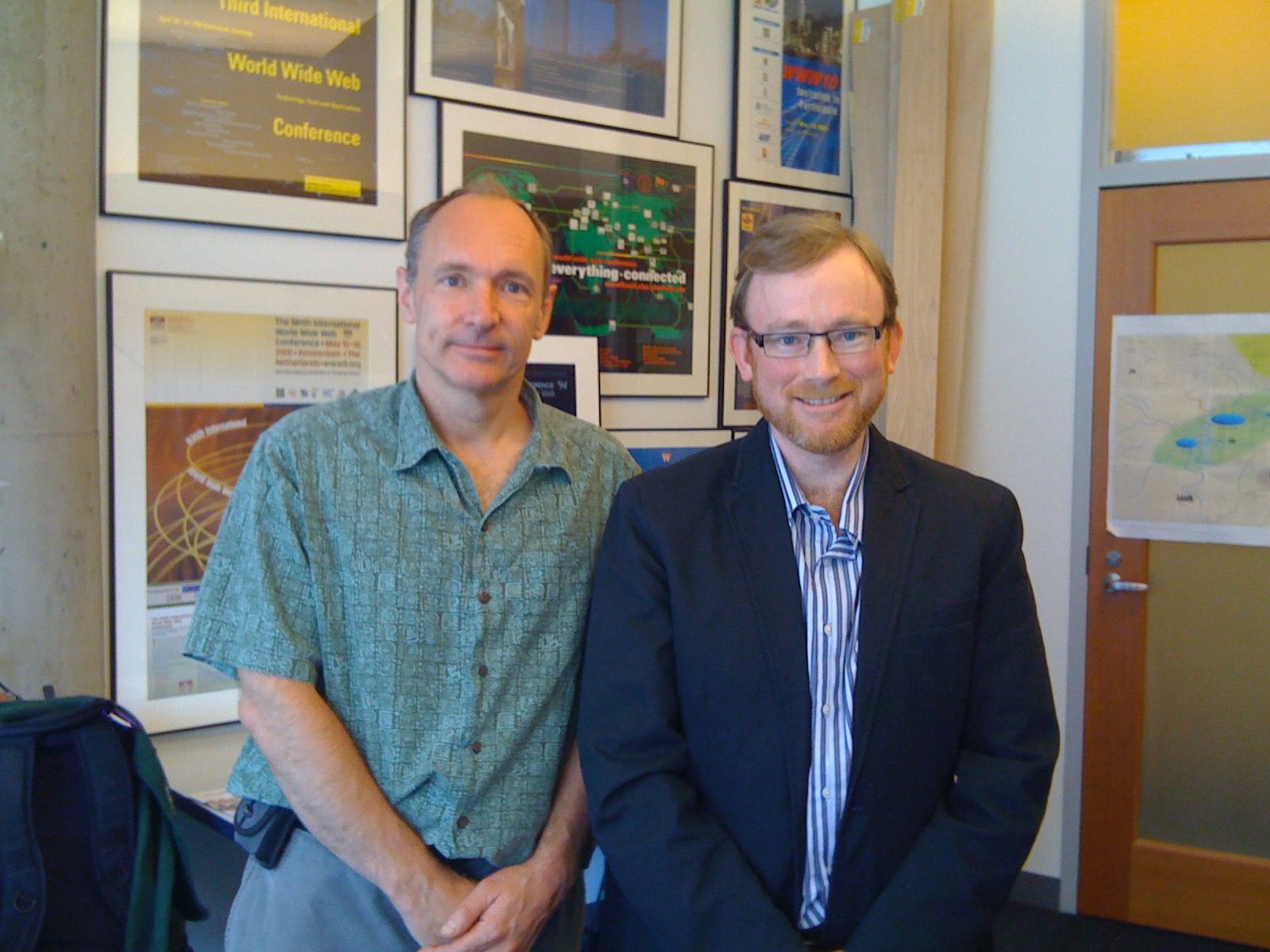

After the interview concluded, we stood up and shook hands again. Up till this point, I hadn’t even thought of asking for his autograph or for a selfie, but fortunately his assistant Amy was much more aware of the situation. She gestured to my iPhone and asked if I’d like a photo of me and Tim. “Oh! Absolutely,” I said, a little too enthusiastically.

It had been a long trip—in a trying year, personally—and I was physically and emotionally drained. But in the resulting photos with Tim, I am beaming and flushed with pride. Here I was, a nobody from New Zealand who less than a decade ago was a mere “Web Knowledge Coordinator,” standing beside the modern equivalent of Johannes Gutenberg. If it hadn’t been for Tim, I wouldn’t have a successful blogging business. Indeed, I might never have found my way in life at all.

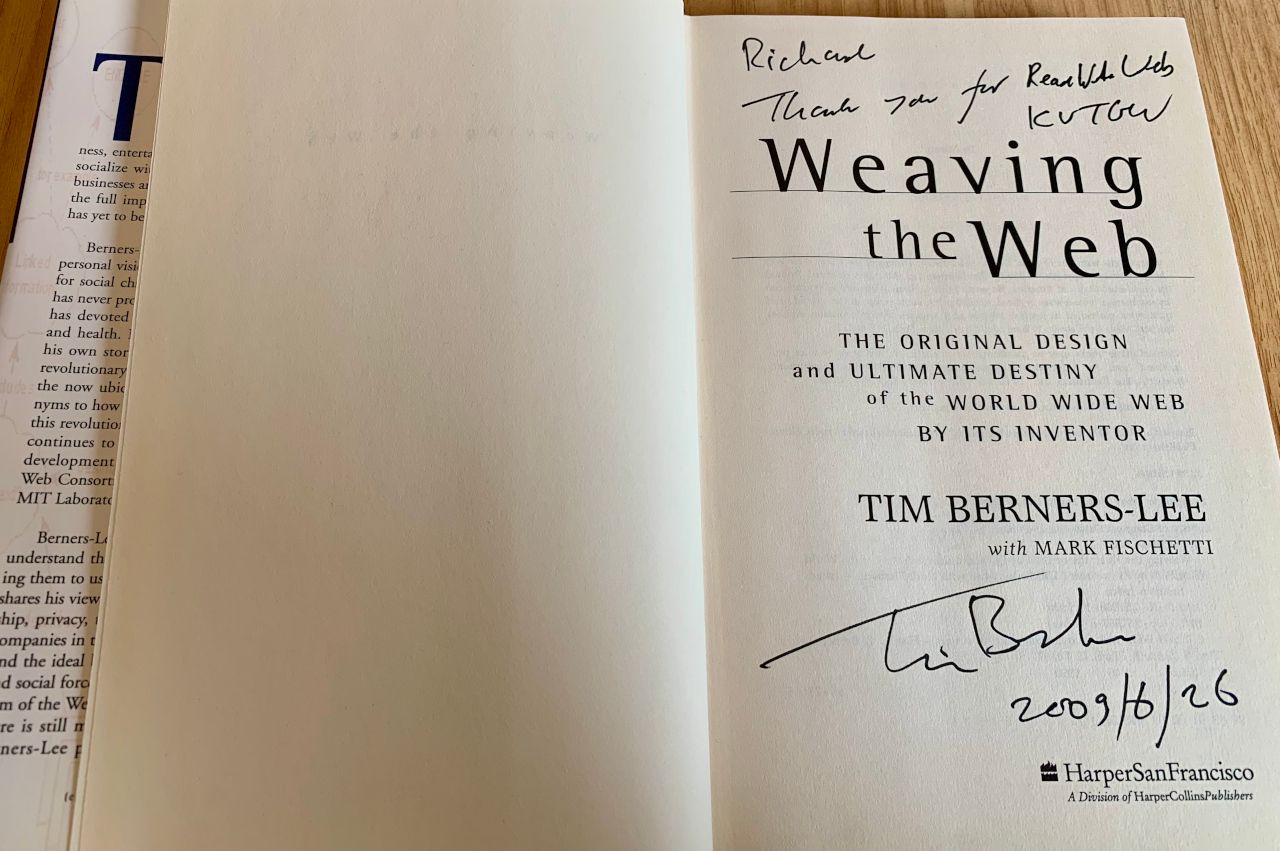

Amy gave my phone back and then took a hardback copy of Tim’s book, Weaving the Web, off one of the shelves. She handed it to Tim along with a black marker pen. He opened it up and wrote on the title page: “Richard, Thank you for ReadWriteWeb. KUTGW.” I didn’t know what the acronym meant until I looked it up back at my hotel: “keep up the good work.”

That gave me the boost of adrenaline I sorely needed as I embarked on the long plane journey back home.

This post is part of my serialized book, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution. View table of contents.

Next up: 040. Why 2009 Was When Big Tech Began To Control Web 2.0

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.