The Core Values of Blogging: Attending BloggerCon 2006

In June 2006, I interview Yahoo at Supernova about its open platform and learn why developers prefer building frivolous Flickr apps. I then struggle to get a word in edgeways at BloggerCon.

For the rest of the week after the Digg podcast call, I attended the 2006 Supernova conference, run by a business academic named Kevin Werbach. It wasn’t as good as the Web 2.0 Conference. In too many cases, panelists and speakers just talked about their own products or companies, and the event was targeted at businesspeople, not developers (the tagline was “Because technology is everyone’s business”). That was true of the Web 2.0 Conference as well, but developers were at least hanging around the hallways there—which wasn’t the case at Supernova.

The most interesting news from my perspective was Yahoo announcing more support for “microformats,” a structured blogging initiative that had emerged the previous year. The theory was that making web content more structured through open-standard formats made it possible (or at least a lot easier) to create new aggregation services. The announcement was part of a larger story that Yahoo was pushing in the industry: that it was now an open platform and that developers were free to build things on its APIs and “mashup” its user data as they pleased.

Flickr was Yahoo’s key product in these claims to be an open platform. It was popular among developers, and it was fun and relatively easy to experiment with photo-sharing data. At the time of the Supernova conference, Flickr supported two microformats on its user profile pages: hCard and XFN (XHTML Friends Network). This basically meant that your name and friend connections were in common data formats, so theoretically other social networks could use that data.

I was offered an interview with two Yahoo executives to discuss its ambitions to be an open platform. One was a Flickr founder, Caterina Fake, who was now leader of Yahoo’s Technology Development Group. The other was Bradley Horowitz, a VP of product strategy.

I arranged to meet them on Friday afternoon in front of the Garden Court restaurant, next to the Supernova conference room at the Palace Hotel. Just before my interview, Bradley did a presentation entitled “Opening Up Yahoo.” In it, he talked about some projects Yahoo had started to encourage third-party developers to build on its content, such as Yahoo! Hack Day and the Yahoo Developer Network. As one example, he mentioned that Flickr had “thousands of people” developing on its API, building everything from “frivolous toys and games” to “real valuable tools like Flickr uploaders and camera phone integrations.”

He also admitted that Stewart Butterfield, Fake’s cofounder (and husband) was at first very resistant to opening Flickr to third-party developers. He said that Butterfield had been involved in a public debate about “opening up the Flickr API to would-be competitors that basically wanted to airlift users’ content out of there.” According to Horowitz, Butterfield eventually came around to the idea that “if it’s done in a reciprocal way, such that we can get the data back into Flickr, that’s actually a good thing for the user.” He added that Yahoo intended to compete with companies that used Flickr data based on the merits of “the Flickr product and community.”

Sure enough, the Flickr web services available in June 2006 allowed developers access to a wide range of data about user photos, including the “interestingness” algorithm. However, Yahoo had carefully ring-fenced commercial development. The Flickr API was “available for non-commercial use by outside developers,” the company said, but commercial use was only possible “by prior arrangement.” That was Yahoo’s way of making sure that other companies didn’t build a better product or app than the Flickr.com website (although frankly, it’s hard to imagine a better site being built, as Flickr was a joy to use).

After that talk, I sat down with Bradley and Caterina. Bradley, then in his early forties, was a neatly dressed man with dark curly hair and rectangular black-rimmed glasses. He regarded me with a mix of politeness and something I interpreted as condescension—or perhaps it was just the supreme confidence of an MIT-educated dot-com founder turned Silicon Valley executive. Caterina was a couple of years older than me. She had shoulder-length dark hair and was wearing an olive-green top over blue jeans. She too was polite but a little standoffish.

After doing my introductory spiel about why I was doing the interview, I realized that neither of them knew much about Read/WriteWeb. I had thought that Caterina, at least, would know who I was. I’d been a member of Flickr since its launch in 2004, and I had blogged about it multiple times since then.

I was a bit unsettled by the pair’s reaction to me. Most of the other tech people I’d met in the United States—startup founders, developers, and product managers—were readers of my blog or had at least heard of it. I had the sense that people wanted to engage with me socially, that we were part of the same network. For whatever reason, I didn’t feel that way in this meeting.

Bradley did most of the talking, and was an expert at keeping to his talking points. But it was something that Caterina said that stood out for me. We were talking about how the goal for Yahoo products was to achieve organic growth via social relationships. Caterina said that if Yahoo did a Superbowl commercial for Flickr, the mass of users that came via the TV ads probably wouldn’t understand the product. But users who came to Flickr via their social network have a better understanding of the product and hence a better chance of using it.

It was an astute observation; sure enough, growth via social connections was the main reason Facebook would take off in the next year or two. It was also the reason why microformats never became popular—the social graph of people interested in them was just too small. Flickr users didn’t care one bit about hCard and XFN. Portability of data wasn’t why people joined Flickr—they just wanted to upload their photos to a cool website like their friends.

Third-party developers were also uninterested, and by and large they did not build Yahoo apps that used microformats. Instead, they preferred building the “frivolous” Flickr apps that Bradley had mentioned in his talk (part of the reason their attention would soon be diverted to Facebook and Twitter). Even early adopters of social software, such as tech bloggers, neglected to use the available microformat features to add semantic information to their profiles.

It was another key lesson for entrepreneurs and developers in the Web 2.0 era: keep things simple and frivolous, and hope users will come to your patch of the web and recommend it to their friends.

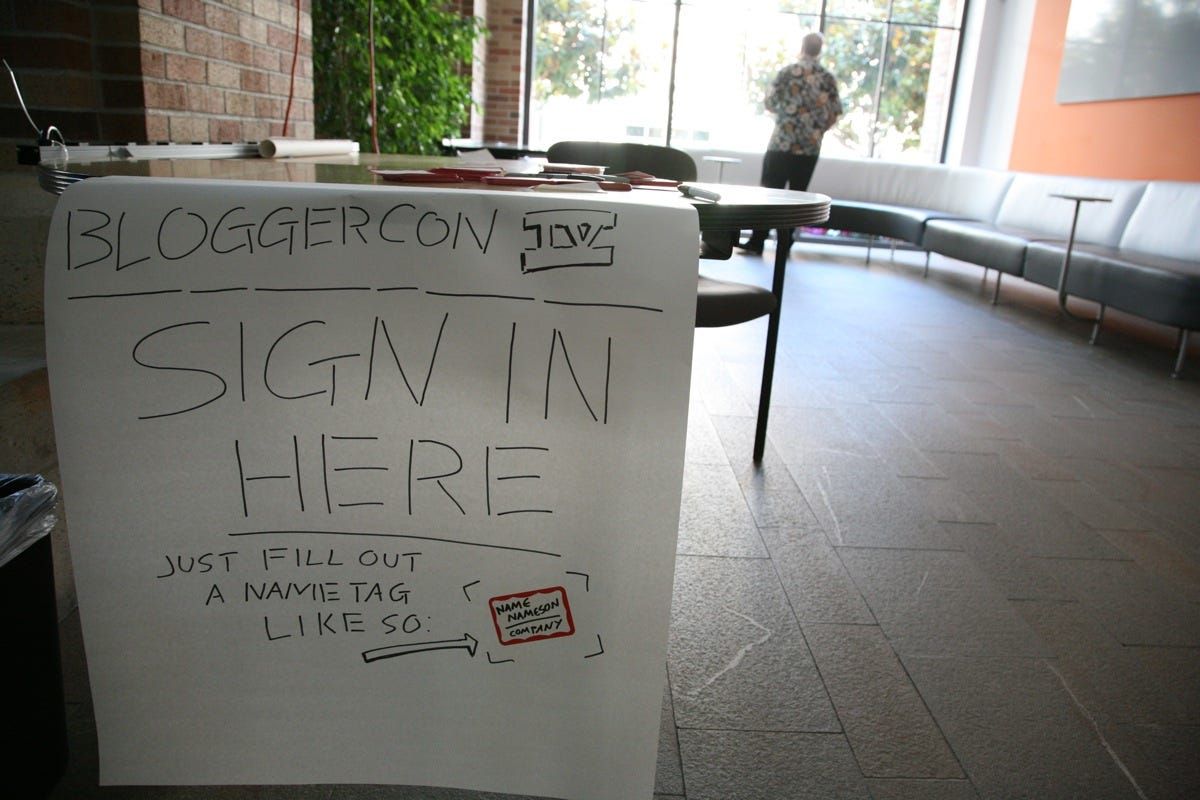

That Friday, I skipped the last day of Supernova to attend the first day of BloggerCon IV. It was an “unconference” jointly run by Dave Winer, the pioneering blogger and software developer, and Harvard Law School’s Berkman Center. I later adopted the unconference format for my own ReadWriteWeb events, which began in 2009. But whereas we wanted to make money from our events, Winer liked to call his BloggerCon unconference “non-commercial”—although, he sold blogging software for a living, so it was obviously a good promotional tool for him.

BloggerCon was held at CNET’s office in San Francisco, so the location was familiar after my meeting with ZDNet editor Dan Farber back in October. Dan was at BloggerCon too, as were most of my blog buddies—Mike Arrington, Gabe Rivera, Susan Mernit, Marc Canter, Chris Pirillo, Anil Dash, and others. And yes, of the fewer than one hundred attendees, most were men—although the ratio was improved slightly by the presence of three founders from a conference called BlogHer.

BloggerCon was also deliberately low-key. When you walked into CNET, a hand-drawn sign to the left of reception pointed the way to the conference room. It was just a black marker pen on a piece of A0 paper, and it couldn’t have contrasted more with the slick, neon-yellow signage of CNET at the reception desk. Another handwritten sign just outside the conference room prompted the attendees to sign in by filling out a name tag sticker.

The event got under way with Winer sitting at a desk facing the attendees. Sitting beside him was Doc Searls, another baby boomer blogger.

“This is sort of a different conference,” Winer told the assembled bloggers in his opening remarks. “If you’ll notice, there’s, like, no audience—although it kind of looks like you’re an audience, I guess, right? It’s tempting, but if you hear somebody use the word audience, correct them and say, participant.”

In principle, there was a lot to like about this approach. As Winer went on to say, “There are plenty of commercial technology conferences where people pitch their products all the time. We don’t need another one of those.” Indeed, Supernova was just such a conference, so I was looking forward to seeing how different BloggerCon would actually be.

Unfortunately, being an introverted and shy person, I didn’t participate much in the discussions that happened throughout the day. It turned out the “unconference” format tended to favor extroverted personalities, which meant the same old people—like Winer, Canter, and Pirillo—were doing all the talking. I blame myself for this; not having the gumption to speak up was another symptom of my long-running self-esteem issues. However, as I wrote in my summary of the event, I also felt the “discussion leaders” could’ve done more to encourage others to pitch in. I made sure that happened when we began running RWW unconference events a few years later.

Overall, though, it was a fun event over the two days, Friday and Saturday. The small turnout encouraged the sense of community that we all felt. Blogging was just starting to become commercial, but at the same time there was a determined effort—by Winer in particular—to make sure that bloggers held onto the “core values” of blogging. These values were ill-defined but emphasized things like authenticity, transparency, and a conversational manner of writing.

To close out the conference, Winer had asked Mike Arrington to talk on this topic. Mike started the session by joking about his previous career as a lawyer—the implication being that lawyers aren’t known for their values. “Because of the support of people in this room, my blog got pretty big, pretty fast,” he continued. “And so I went from the good times, when you start getting a couple of comments [and] ‘oh there’s a conversation taking place,’ to the real hate stuff, that we all probably deal with every day.” He added that he had “more hate comments today and more troll comments today, than actual real comments.”

This wasn’t something I had experienced to the degree Mike had. Partly this was because his site was significantly bigger than mine, but also, Mike’s blogging style was combative. He liked to poke and prod on issues in order to get reactions from people. My blogging style was more balanced—more journalistic, I suppose, although I didn’t think about it that way at the time. The key difference between us was in who we wrote for. I approached topics from the perspective of a developer or an early adopter—trying to discover what can be built with a technology such as RSS and what a proactive user can do with it. Mike approached topics from a product or market perspective, which meant his posts were more attractive to a consumer or business audience—readers who were just beginning to discover tools like YouTube and Facebook and wanted to know more about them.

Because he now reached a broad audience, Mike experienced the downsides of the “wisdom of the crowds” before me. Hate comments and trolling would, of course, become commonplace on social media in the years to come. It wasn’t a new phenomenon, either; popular newsgroups and forums in the 1980s and 1990s had attracted plenty of shitposters and trolls. But the attacks did perhaps feel more personal, since blogs were so closely tied to the personality of an individual. Certainly Mike thought so.

He also thought bloggers themselves were beginning to leave nasty comments. “I think there’s a trend toward people, non-anonymously, getting more vicious in their blogging and in their comments,” he said, which brought the topic back to what the “core values” for bloggers were. In the discussion that followed, various people told stories of their own experiences with trolls. But there was no resolution or answer to the question whether the core values of bloggers were beginning to erode.

I didn’t think this was a useful discussion, and even if I had been called upon (which I wasn’t), I didn’t have a good troll story to tell. So I began to tune out, checking my blog stats and tech.memeorandum while the debate raged on. I was also hanging out in the IRC backchannel, where many of my fellow introverts were chatting. In this way, BloggerCon was just the same as Supernova—if you lose interest in a session, there’s always your laptop to look at.

Eventually, Mike changed the topic to something that was front and center for emerging pro bloggers like me: conflicts of interest. He wanted to explore the more subtle ways that this can influence a blogger. “What if I’m investing in a company, and I’ve disclosed that, but they have a competitor?” he said. “Or, you know, just the subtle ways that we can all push things we like and not push things we don’t like—where’s the line there?”

This was something I would grapple with in the coming months, as I landed new sponsors. Zoho was in the web office space and Pageflakes was in start pages—two product categories that I loved to write about. If anything, I ended up trying to avoid writing about my sponsors; over the following years, I wrote more often about Google Docs than Zoho, and Netvibes more than Pageflakes. In retrospect, I was perhaps a little unfair on my sponsors when it came to editorial.

The prevailing wisdom of the BloggerCon attendees was that bloggers should be very transparent: if you are writing about a topic where you might’ve been influenced by a sponsor, or even a friendship, then disclose it. But my ZDNet editor Dan Farber had an even deeper cut. “You have to know in your heart whether you’re being honest, and [that] you’re preserving your integrity, because that’s all you have,” Dan said. “You blow that away, you’re done—you’re finished.” Om Malik, another longtime journalist turned blogger, had said a similar thing earlier in the session.

As RWW began turning into a media business over the rest of 2006, those words from “proper journalists” (a phrase I used a fair bit back then) were my guiding star. Integrity was the key—whether it was how you communicated on your blog and via comments on other blogs or how you dealt with conflicts of interest. We could talk about core values at an unconference until the cows came home, but ultimately a blogger only had one person to answer to: themself.

Lead image: Me and Greg Narain at BloggerCon IV, June 2006; photo by Chris Heuer

This post is part of my serialized book, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution. View table of contents.

Next up: 017. Gnomedex 2006 and My Corporate Blogging Adventure

Buy the Book

My Web 2.0 memoir, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley's Web 2.0 Revolution, is now available to purchase:

- Paperback, US$19.99: Amazon; Bookshop.org

- eBook, US$9.99: Amazon Kindle Store; Apple Books; Google Play

Or search for "Bubble Blog MacManus" on your local online bookstore.