Blogging in 2003–2004: The Early Years of ReadWriteWeb

A naive young man from New Zealand explores the blogosphere with a weblog called 'Read/Write Web'.

I was a long way from Silicon Valley at the beginning of 2004, both geographically and in frame of mind. I’d recently turned 32, had fine strawberry blond hair that I obsessively brushed to keep neat, innocent-looking blue eyes covered by a pair of rectangular, semi-rimless glasses, and a ginger goatee with neatly trimmed sideburns. For my blogger profile photo, I chose to use a selfie taken slightly from the side and with the photo cropped at my eyebrows, so that the top of my head was cut off. It accentuated my goatee and sideburns, and gave me a kind of Max Headroom look. This was several years before selfies became a trend, so in this photo I was not looking directly into the camera. I was too awkwardly shy to do that anyway. Instead, I’m self-consciously staring into the distance, as if I’m dreaming about what life must be like in California.

“I’m a writer, web technology analyst and web producer,” I described myself on my blog at the beginning of 2004. “The latter one pays the mortgage right now, but I’m working on increasing the influence of the first two in my career.” And that, I wrote, was where my weblog came in. At the time, I worked for Contact Energy, one of New Zealand’s leading power suppliers. As hinted at in my profile page, I found my day-job rather dull — I managed the internal and external websites of the company, using a mix of off-the-shelf content management system software and whatever web publishing products Microsoft and Macromedia had at the time. The topics I wrote about in my blog were many years away from being a part of corporate websites.

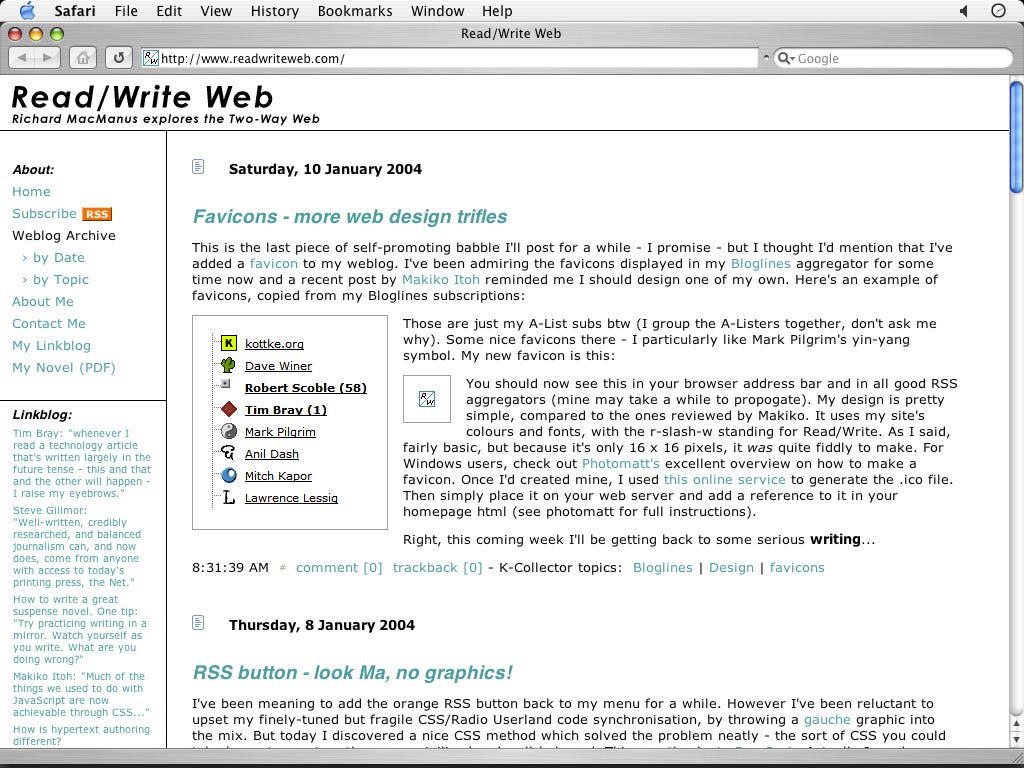

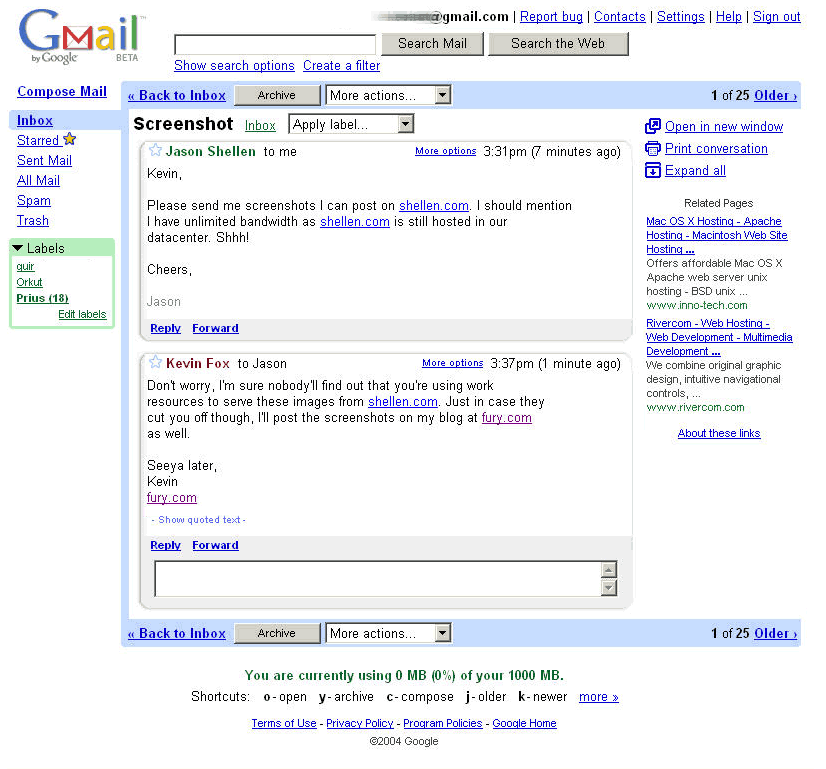

Since starting it in April 2003, my weblog had mostly focused on analysis of the latest web technology trends — but it was also a “learn by doing” situation. I’d spent a good deal of time organizing the structure of the blog (creating the navigation, setting up subscription formats, deciding what to put in the sidebars, and so on), and I’d completed a full “tableless CSS” redesign in September. But I’d also veered off track at times, such as my participation in NaNoWriMo — National Novel Writing Month — an annual challenge to write a 50,000-word novel in 30 days, over the month of November 2003.

Behold, my tableless CSS design. Safari screen capture from 10 January 2004.

The “blogosphere” in 2003-04 was largely made up of geeky people like me, who treated the medium as a mix between an online journal and a tech experiment log. I enjoyed testing various new web technologies and applying them to my blog. At one point, I was “diving into XSLT to try and develop something interesting for my weblog’s topic-based navigation” (trust me, you don’t need to know what XSLT stands for now). But blogs at that time were also personal, a reflection of their author’s personality. I often referenced literature and music in my posts, such as comparing the Semantic Web to the hunt for the white whale in Moby Dick, or starting a post about being a web generalist with a review of The Velvet Underground’s song “What goes on” as performed on their 1969 Live album.

Sometimes I look back on my early posts and cringe — did I have to write a post entitled “Liv Tyler waved at me” at 9.10pm on December 1, 2003? No, I didn’t, but earlier that day I’d attended a street parade for the world premiere of The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, a movie by fellow Wellingtonian Peter Jackson. It had been a beautiful sunny summer’s day in Wellington and I felt proud to be a kiwi — we were hosting a Hollywood party! In writing that post, I was subconsciously connecting Jackson’s Hollywood dream come true to my own Silicon Valley dream.

Silicon Valley seemed very far away at the time, but at least I felt a sense of communion with it, thanks to blogging software and the World Wide Web.

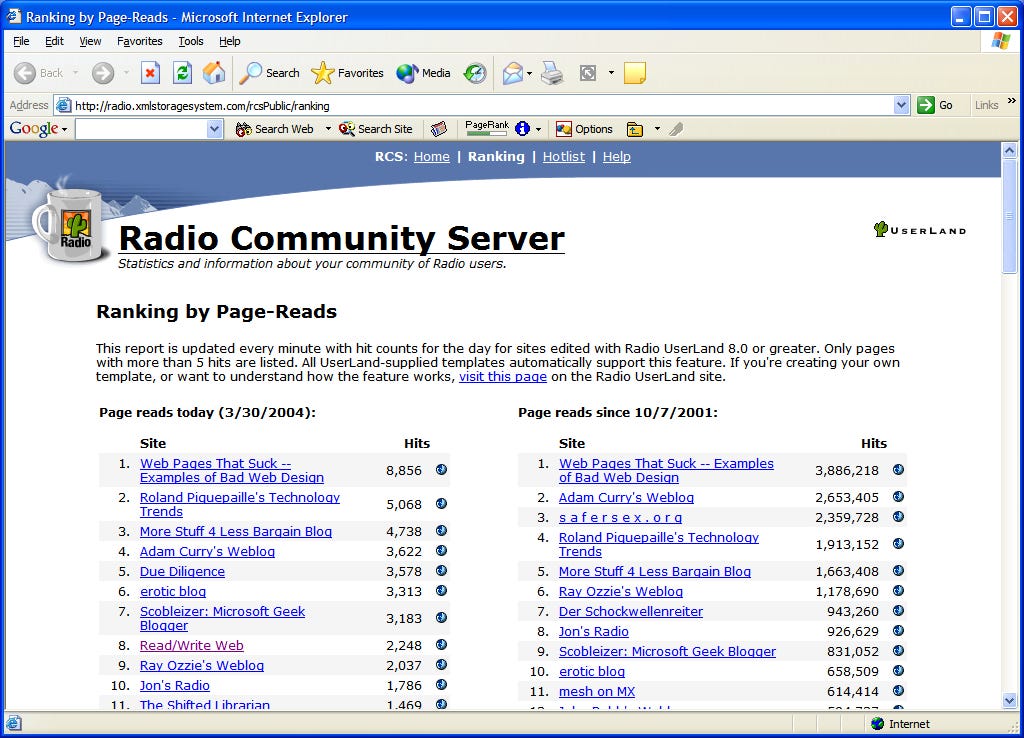

Up until May 2004, I ran my blog on Radio Userland, desktop blogging software created by Dave Winer. On this particular day, 30 March 2004, RWW was ranked 8th in the community — just ahead of future Microsoft CTO Ray Ozzie. In early May, I switched to Movable Type, a browser-based blog platform.

During the first half of 2004, I was trying to figure out my role as a tech blogger and what topics I should focus on. I didn’t know it at the time, but there were several pivotal web product launches that would help shape the future of ReadWriteWeb.

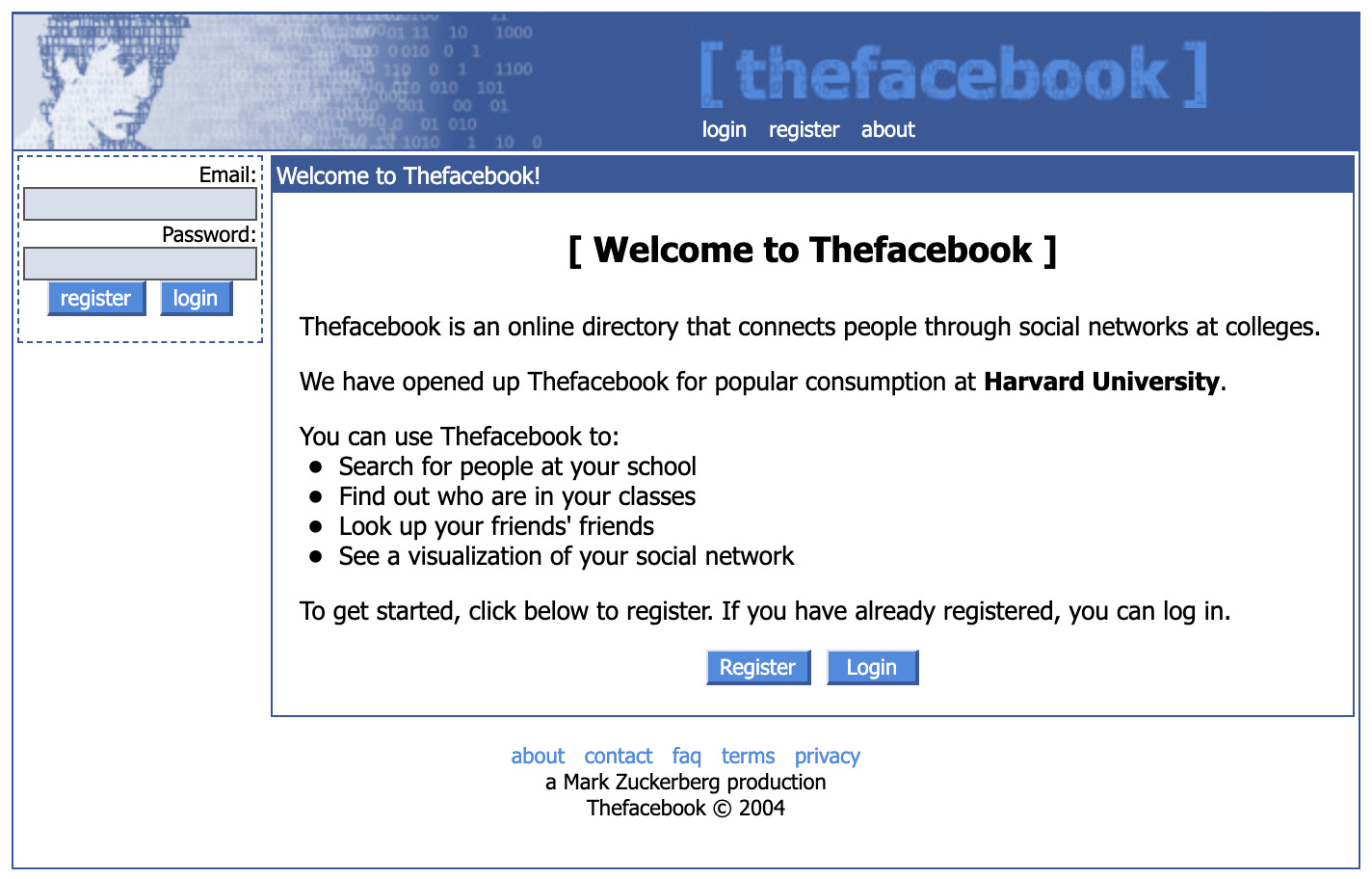

In February, a young Harvard student named Mark Zuckerberg launched a new site called “Thefacebook.” Initially, its only users were fellow Harvard undergraduates, but by the following month students from Columbia, Stanford and Yale had joined the fledgling social network. Needless to say, all this was completely off my radar — given I was halfway across the world and not a student at an elite American university.

Earliest Wayback Machine copy of “Thefacebook”, 12 February 2004.

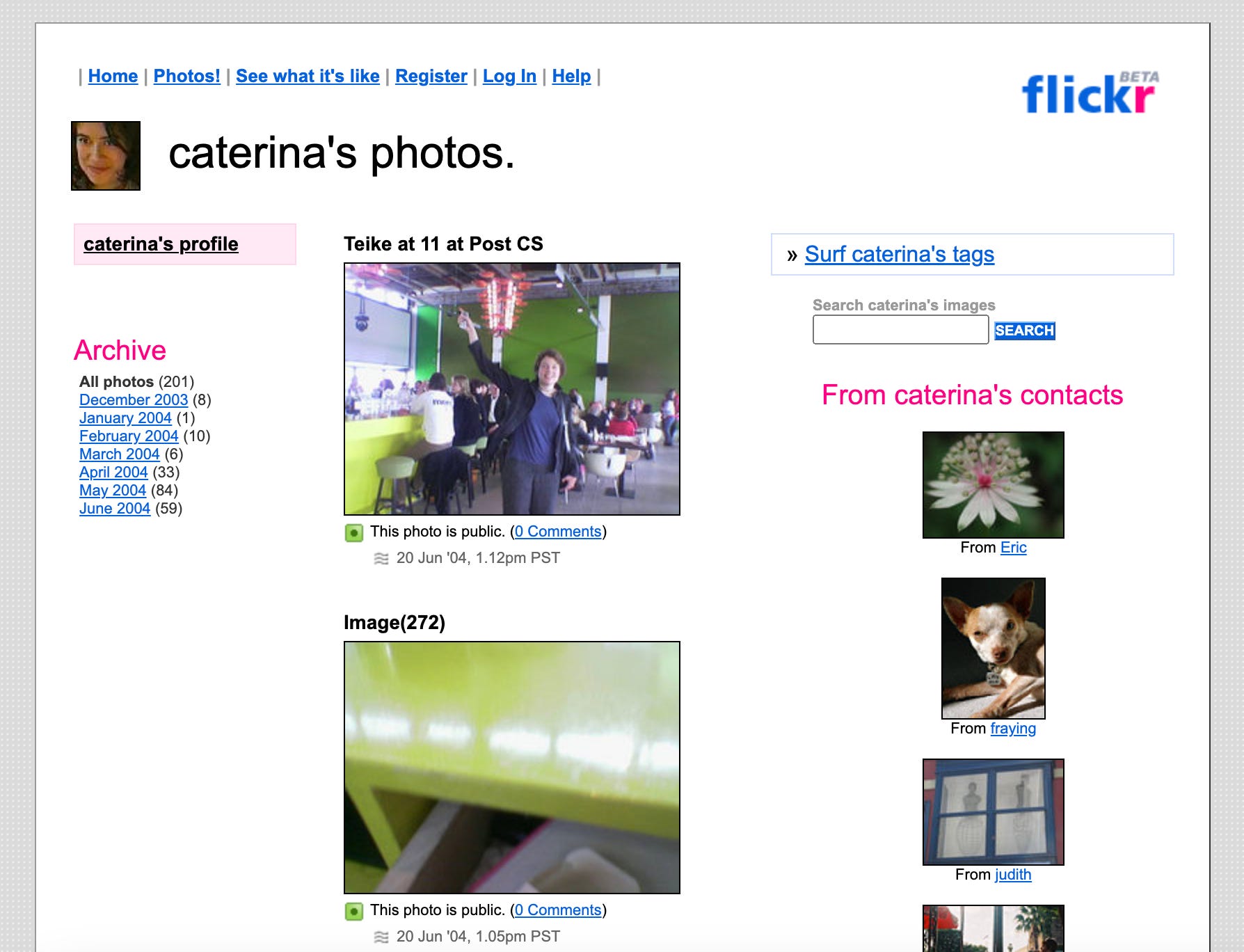

Also in February 2004, a Canadian couple — Stewart Butterfield and Caterina Fake — launched Flickr, a photo-sharing website. While I wasn’t immediately aware of Flickr, I was aware of the company that had launched it: LudiCorp. I had even written a couple of posts about them; or more specifically, about its online game called Game Neverending, which I’d discovered at the end of 2003. I’d done one of those frivolous online questionnaires, this one entitled “What kind of Social Software am I?” I could’ve been a wiki, a blog, the entire blogosphere, or other varieties of “social software” (the term we used at the time). Turns out I was Game Neverending, which I’d not heard of until that day. So I looked it up and discovered it was, as I put it at the time, “a virtual world in which creativity and social interaction are the main drivers.”

I never did get into the beta of the game, probably because by the time I discovered it LudiCorp had pivoted to Flickr — which had begun as a mere feature of Game Neverending. I joined Flickr in August 2004, the same time as I expressed an interest in exploring “multimedia blogging.” By this time, social software was well and truly in the air. I was also using a very geeky site called del.icio.us, which somehow made bookmarking a link a social activity (the early success of del.icio.us in 2004 showed how nerdy the blogosphere was back then!).

Flickr co-founder Caterina Fake’s Flickr homepage, June 2004. Note the “beta” tag on the logo; this became a familiar sight in Web 2.0!

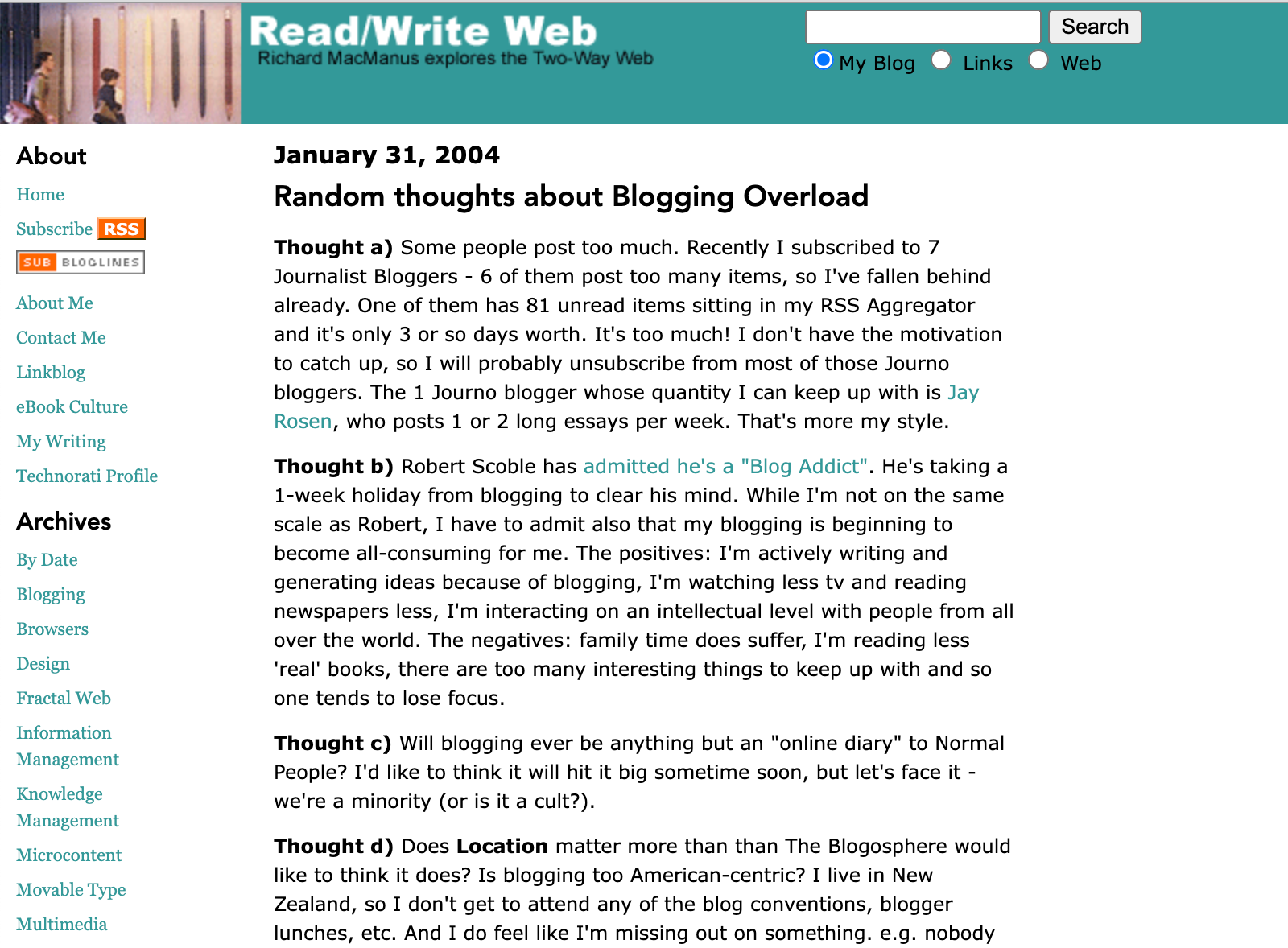

But arguably the most impactful web product of 2004, certainly from a usage point of view, was Google’s new web-based email service, Gmail. I joined it in July, a few months after the launch. Gmail was invite-only, but fortunately one of my blogger friends sent me an invitation code. Its most newsworthy feature at the time was the one gigabyte of storage space that Gmail offered, which was more than 100 times what Yahoo and Microsoft offered. But what really stood out to new users was Gmail’s use of DHTML (Dynamic HTML), a technique using JavaScript that enabled a webpage to refresh itself in the background.

Funnily enough, Google hadn’t invented this snazzy technique — in fact, it came from Microsoft in 1997. But Gmail was the first widely used consumer web product to base its user interface around DHTML. Later, in early 2005, a new term would be coined for this functionality: Ajax (“Asynchronous JavaScript and XML”). But regardless of the name, Gmail’s interface seemed magical to many of us in mid-2004 — for the first time, a major web product seemed as sophisticated as a desktop app on Windows PC or Apple Macintosh.

A Gmail screenshot from 2 April 2004, the day after its launch. Via Kevin Fox and Jason Shellen, who worked at Google at the time.

As if to prove that a new web era was beginning, Marc Andreessen quietly launched his third startup around the same time I joined Gmail. No doubt he’d heard all the buzzwords being bandied about within Silicon Valley and by bloggers like me — social software, two-way web, user-generated content, tagging, microcontent, and so on. The question for Andreessen, already a millionaire many times over, was what to do about it. He had dabbled in angel investing already; and indeed would invest in his friend Reid Hoffman’s social networking company, LinkedIn, later in the year. One option, then, was to use all his connections and capital, and become a VC. But no, he decided it wasn’t time for that yet. He still wanted to be “in the arena,” as Theodore Roosevelt had once famously put it. (Roosevelt’s full quote — “It is not the critic who counts […] the credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena” — has since become a rather obnoxious Silicon Valley maxim).

Andreessen’s third act would come to be called Ning. He later said that at the time he started Ning, he was fascinated with Reed’s Law. It’s a form of network effects, stating that a network becomes more valuable when people can easily form subgroups to collaborate. The initial idea of Ning was to allow users to create “social apps” for groups. “Friendster hadn’t worked, MySpace was just getting a little bit of traction, and Facebook was still at Harvard,” he explained. “What we knew worked were focused applications: Craigslist, eBay, Monster. So our idea was to bring social into these domains, in the form of apps that groups could run for themselves: their own job boards, their own selling marketplaces, and so on.”

It was this and similar theories of social software that were firing the imaginations of entrepreneurs and bloggers alike in 2004.

Already, though, I had noticed a dark underside to the nascent social web. For all the geeky excitement and feeling of camaraderie that blogging and early social apps gave me, in my private notebooks I had started to complain about “the social pressures of the blogosphere — the need to be linked (loved), the quest for attention.” Later, in a public post, I mused further on the emerging attention economy. “It may be a democracy of ideas, but sometimes it feels like a horserace,” I wrote.

Blogging about blogging; a common activity in 2004. Via Wayback Machine.

These were early warning signs of what social media would turn into in the 2010s, on a mass scale. But I put these premonitions of a darker side to Silicon Valley out of my mind. In 2004, as far as I was concerned, I was off to the races with my blog.

Lead image: My weblog avatar in January 2004, age 32.

This post is part of my serialized book, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley’s Web 2.0 Revolution. View table of contents.

Next up: 003. The First Web 2.0 Conference

You're reading Cybercultural, an internet history newsletter. Subscribe for free, or purchase a premium subscription. Your support for this indie publication would be greatly appreciated.