Betting on Web 2.0: High Stakes Blogging

My trip to Silicon Valley for the Web 2.0 Summit in November 2006 ends with a poker game in Atherton. Meanwhile, Time Magazine names us all 'Person of the Year.'

On Friday I made my way from San Francisco to the TechCrunch ranch in Atherton, about forty-five minutes south down the 101. Mike was as busy as usual. I brought up the RWW Research idea that I’d chatted to my friend Fergus about, but he was too absorbed in his own expansion plans to care. Simply put, he was on a different level now. He was at the epicenter of the Silicon Valley startup scene, rather than skirting the periphery like me. A recent Wall Street Journal article had called Mike a “power broker” in the industry and quoted him as saying, “I want more page views than CNET in two years.”

“TechCrunch Site Makes Arrington A Power Broker,” The Wall St Journal, November 3, 2006

The article was written partly in response to Mike’s recent post on CrunchNotes, his personal blog, in which he vigorously defended himself from accusations of conflicts of interest. “Techcrunch is all about insider information and conflicts of interest,” he’d written. “The only way I get access to the information I do is because these entrepreneurs and venture capitalists are my friends.”

One of his friends was a twenty-six-year-old Australian entrepreneur, Nik Cubrilovic, who was staying with Mike when I arrived that Friday. Nik ran an online storage startup called Omnidrive and in his spare time wrote guest posts for TechCrunch. Nik was friendly and charismatic, although over the next couple of years Omnidrive would run into financial difficulties (and eventually fail altogether) and he would fall out with some of his fellow Australian entrepreneurs—one of whom said he invested $100,000 and lost it all. None of this was apparent in November 2006, though. Nik just seemed like a smart, ambitious young guy. I also noted that Mike relied on him to provide technical support and give him background information about the startups he wrote about—similar to what Fred Oliveira did for him the previous year.

After I arrived at Mike’s place, Nik added me to an email thread with a bunch of Australian entrepreneurs about a gathering he was organizing for Saturday. Among the people on the thread were Mike Cannon-Brookes (a founder of Atlassian and future billionaire), Marty Wells (founder of Tangler, which I had done some analysis work for), Mick Liubinskas (a Sydney native who worked for Tangler), Chris Saad (a smart product guy who was also active in web standards work), and Cameron Reilly (a Brisbane native who ran a podcast network).

OG podcaster Cameron Reilly talking my ear off, Nov 2006. Photo by Ouriel Ohayon.

We all met up on Saturday afternoon, at Coupa Café on Ramona Street in Palo Alto. The shop talk about startups and the Web 2.0 Summit soon turned to planning a game of poker. Marty purchased four hundred candy poker chips, we stocked up on alcoholic refreshments, and then we drove back to Mike’s house in Atherton.

It was a memorable night, at least for those of us who didn’t drink bourbon straight from a tall glass; I’ll refrain from mentioning who that was, but he apparently threw up in Marty’s car on the way back to San Francisco. Throughout the night there was a lot of bad singing and terrible jokes, and even some dog wrestling (poor Laguna). The poker game itself was played mostly for laughs, although the two Mikes—Cannon-Brookes and Arrington—became increasingly competitive with each other as the evening progressed. I was content to have fun with the cards and enjoy the geek male bonding; most of the others were similarly inclined. Cameron, who was sat next to me, occasionally poked fun at me for being a New Zealander and was generally a hard-ass at the table.

For part of the night, I was cleaning up! But it didn’t last (story of my career); from left to right: Nik Cubrilovic, Mike Cannon-Brookes, Cameron Reilly, me, Mick Liubinskas; photo by Chris Saad.

I don’t remember who won the poker game, or if there even was a winner, but we ended the night playing liar’s dice—a game that involved trying to pick who is bluffing. This ended with a Mike vs. Mike duel. Despite his long, wavy hair and Aussie bloke persona (most sentences began with the word mate), it became clear that Cannon-Brookes had an ultracompetitive streak. He was still in his twenties at this point but was already building tremendous value with Atlassian. It would eventually IPO on the NASDAQ at the end of 2015, which made Cannon-Brookes and cofounder Scott Farquhar Australia’s first tech-startup billionaires. He was pretty good at card and dice games too.

The games ended when Cannon-Brookes lost his last liar’s dice on a technicality, which threw him into a tizzy. The other Mike laughed uproariously, having been declared the winner. I think Arrington left on that high note and went to bed, while the rest of us continued to empty his drinks cabinet. This may’ve been when the dog wrestling occurred, as I can’t imagine Mike letting this happen to his beloved chocolate lab otherwise.

Same lineup, but with Chris on the right; photo credit, Chris Saad.

In many respects, 2006 was a breakthrough year for Read/WriteWeb. December revenue for the site was over $14,000, with most of it coming from the sponsor adverts in the right-hand sidebar. FM Publishing revenue was now about a quarter of the site’s revenue. I had no employees yet and minimal costs, so it was nearly all gravy.

The site was growing every month in page views and subscribers. December exceeded 370,000 page views, continuing a pattern of steady growth of around 10 to 15 percent each month. I had around 40,000 RSS and email subscribers, which in the heyday of RSS readers was a regular and loyal readership. I was marketing RWW to potential sponsors as “the foremost Web 2.0 analysis blog” and noted that it was among Technorati’s Top 100 blogs in the world (it was number 68 by the end of the year—still well behind TechCrunch at number 4 and even GigaOm at 35, but still I was pleased to be on the list).

Read/WriteWeb homepage, December 2006; via Wayback Machine.

Despite the rosy statistics for RWW, all the hard work I was putting into it was taking a toll on my personal life. By the end of the year I had moved out of my family home and was temporarily staying with my parents. I’d been having trouble communicating with my wife, and she had become intensely jealous of my overseas trips—with some justification, as we had still not gone on a honeymoon after our marriage back in January. It was all too much, and I moved into a two-bedroom rental early in the new year so that I could have some space to try and work through my issues. I was, of course, most worried about the impact the separation would have on our five-year-old daughter, but things had come to a head with my wife.

I also did not want to drop the ball with RWW, which had real momentum now; I was enjoying the thrill of building my own business and regular trips to Silicon Valley. Making a success out of tech blogging had changed me as a person, and mostly in a good way: I’d become more self-confident and felt that I’d finally discovered what I wanted to do with my life. RWW had started out as my online avatar, but it was much more than that now. It was a growing business—a media brand—and I knew that in 2007 I would be bringing other people in to help me write the articles and run the company. It was a dream come true, from a career perspective.

All that said, I was well aware that my work and life were completely unbalanced, with most of my time and energy going into work. I had a lot to figure out.

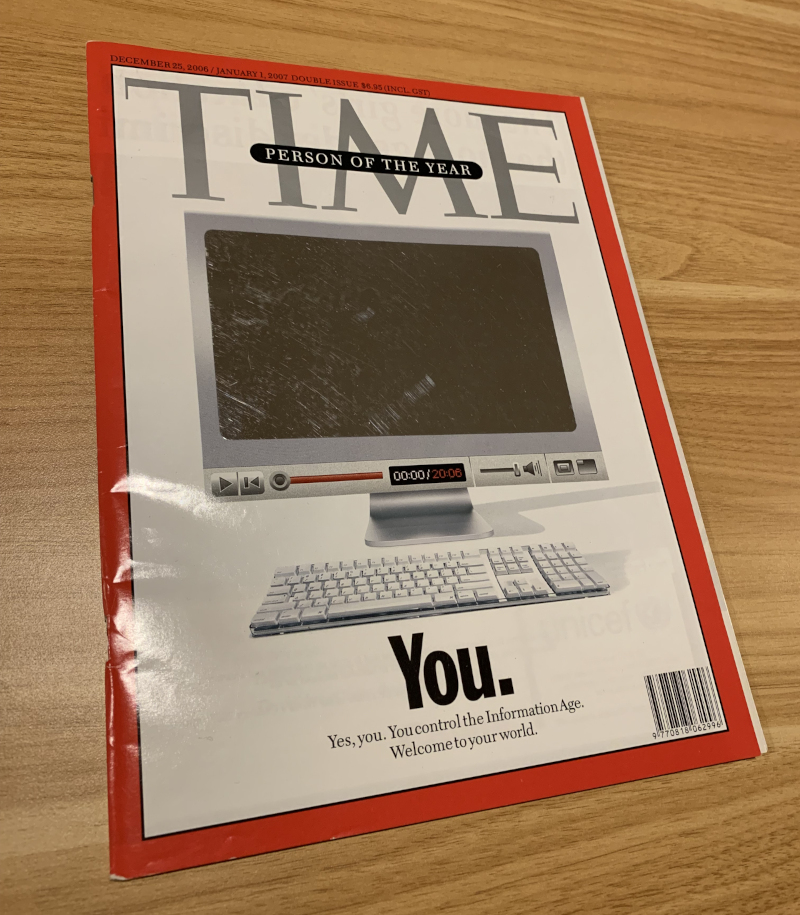

For all the problems in my personal life, things were looking ever more promising in the internet industry. In its December 25, 2006, issue, the venerable publication Time named the web-powered “You” as its Person of the Year. The accompanying article, written by Lev Grossman, used the term Web 2.0 a few times (attributed to “Silicon Valley consultants”), and there was talk of an internet “revolution.”

My copy of Time Magazine’s year-end issue, 2006.

Reading the article now, with the benefit of hindsight, it did a great job of capturing both the hope and the concerns of the Web 2.0 era. Grossman acknowledged that tools such as blogs, YouTube, and social networks were “a massive social experiment” and perceptively noted that “Web 2.0 harnesses the stupidity of crowds as well as its wisdom.” But he ended on a note of rose-tinted optimism common to that era: “This is an opportunity to build a new kind of international understanding, not politician to politician, great man to great man, but citizen to citizen, person to person.”

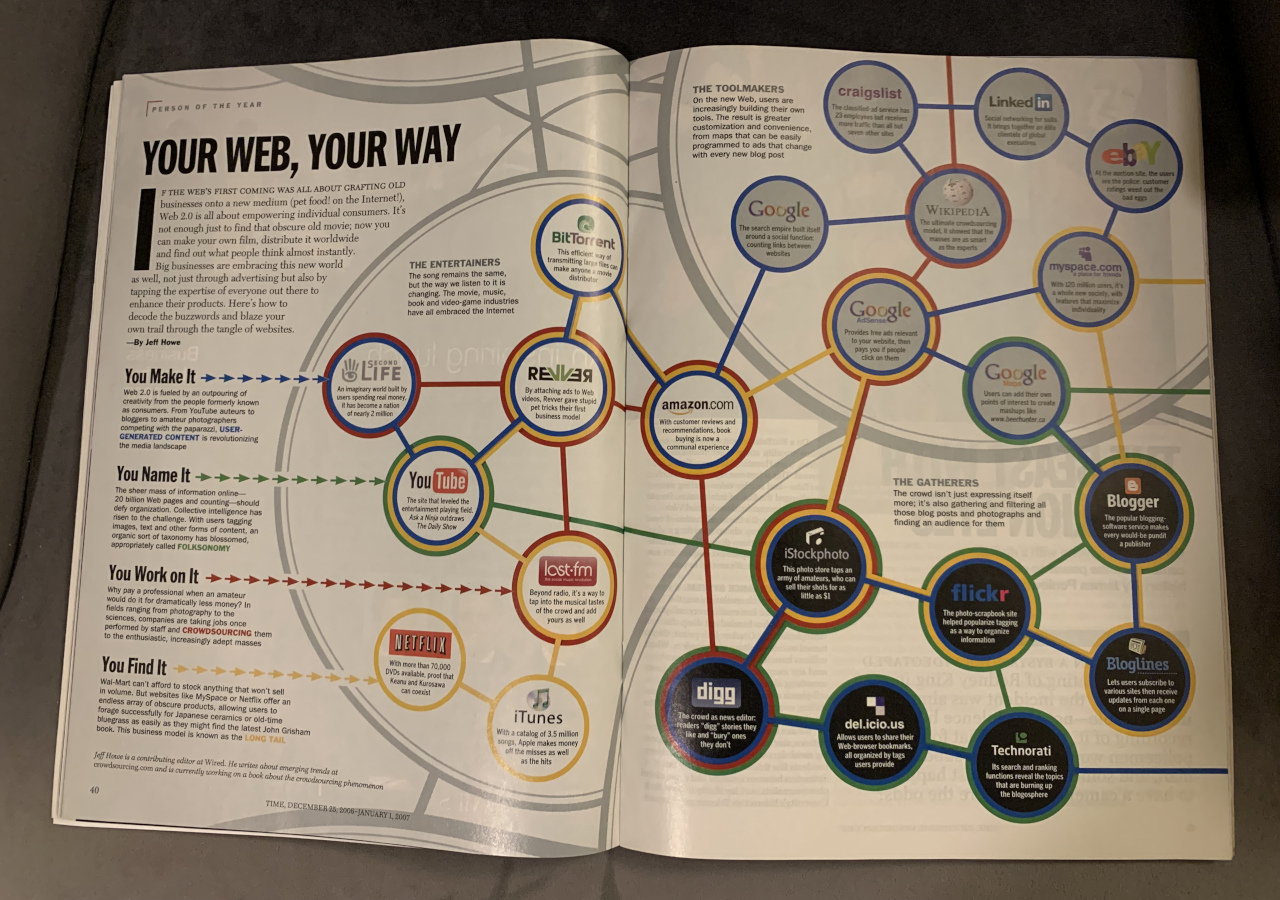

The web landscape at the end of 2006, according to Time Magazine.

Time’s front-page coverage validated Web 2.0 as a cultural movement, which helped to bring RWW to the attention of even more mainstream people as the new year began.

Lead image: Poker night at Mike Arrington’s house, November 2006: Mike Cannon-Brookes, Cameron Reilly, me; photo by Chris Saad.

This post is part of my serialized book, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley’s Web 2.0 Revolution. View table of contents.

Next up: 021. Read/WriteWeb Network Launches Amid iPhone Debut

You're reading Cybercultural, an internet history newsletter. Subscribe for free, or purchase a premium subscription. Your support for this indie publication would be greatly appreciated.