The Birth of Cloud Computing and Team Read/WriteWeb

In 2006, Read/WriteWeb gets a redesign and I begin to grow the team, starting with a couple of engineers who help me explain Amazon Web Services and GoogleOS.

During the second half of 2006, more and more of my focus was on building up Read/WriteWeb. In July 2006 I announced a major redesign of the site. The previous design had been a thin two-column layout on a white background, with red font for the headers and links. It featured a circular logo with the letters R and W inside, which I’d created in Photoshop using the yin-yang symbol as inspiration. Up till this point, I had done all the web design and development myself. This work was serviceable, but I needed a bit more design flair to keep up with TechCrunch, GigaOm, Mashable, and other Web 2.0 blogs. Also, the layout needed opening up to accommodate more advertisers and sponsors.

RWW design in May 2006, before the big redesign.

The new design, which went live in July, was certainly wider and more colorful. It had a red background with a cream-colored header and sidebar. It was now much roomier in the sidebar and header areas, with plenty of space for display ads. The main text area remained white, and I stuck with the red links. I had a new logo, too, although this was the weakest part of the new design. The yin-yang still anchored the top left of the page, but the letters had been removed, and the site name—Read/WriteWeb—appeared in a serif font in red and grey in the cream-colored header.

The new design doubled down on red. Screenshot from July 2006.

The design was a step up from my previous hacked-together designs, but it had clearly been a little rushed—there were glitches, especially with the latest Internet Explorer browser (version 7). The designer was Kevin Hale of Particletree, who was a member of the Web 2.0 Workgroup. I’d approached him in May, noting that I didn’t have the money to pay him, but perhaps we could do a quid pro quo arrangement? Kevin was working on an online form builder called Wufoo. This wasn’t a new idea, but his online form generator was powered by Ajax, the web development technique that had helped define Web 2.0. He agreed to design a new template for me in exchange for a review of Wufoo when it launched.

Kevin seemed to be very busy with Wufoo, so his communication was sporadic. I suspect he left my project till the last minute. Regardless, by July he’d delivered me a new template. Wufoo had recently gotten funding from Y Combinator, a now-famous Silicon Valley incubator that was then just over a year old. So he was onto bigger and better things, and we quickly lost contact.

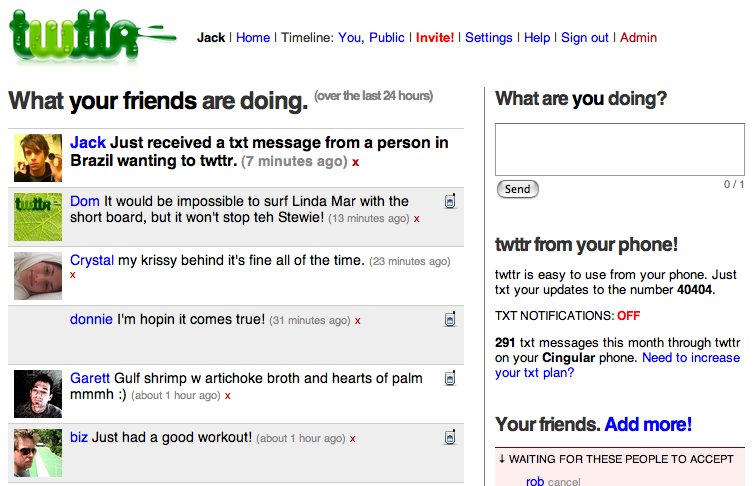

Incidentally, the day after I announced my redesign, a new service called Twttr launched. It was a text-based application and only available in the United States. Users were prompted to share short status updates with a group of friends by sending a text message to a specific number (40404). Since Twttr was available only to those with a US phone number, I couldn’t even test it out. Indeed, I probably found out about it only via a TechCrunch post—Mike had noted that “a few select insiders were playing with the service at the Valleyschwag party in San Francisco last night.” I did mention the new product in that week’s RWW Weekly Wrapup, but since I couldn’t use Twttr I promptly forgot about it.

Screenshot of Twttr in 2006 via Josh Sowin

Around this time I also began accepting offers from entrepreneurs and developers to write guest posts for RWW. The site had gained in popularity over 2006, so it was potentially a way for people to get attention for their own startup or passion project. I was happy to bring new writers on board, since it lifted some of the creative burden off me. The second regular contributor to RWW, as it turned out, became one of the site’s enduring names.

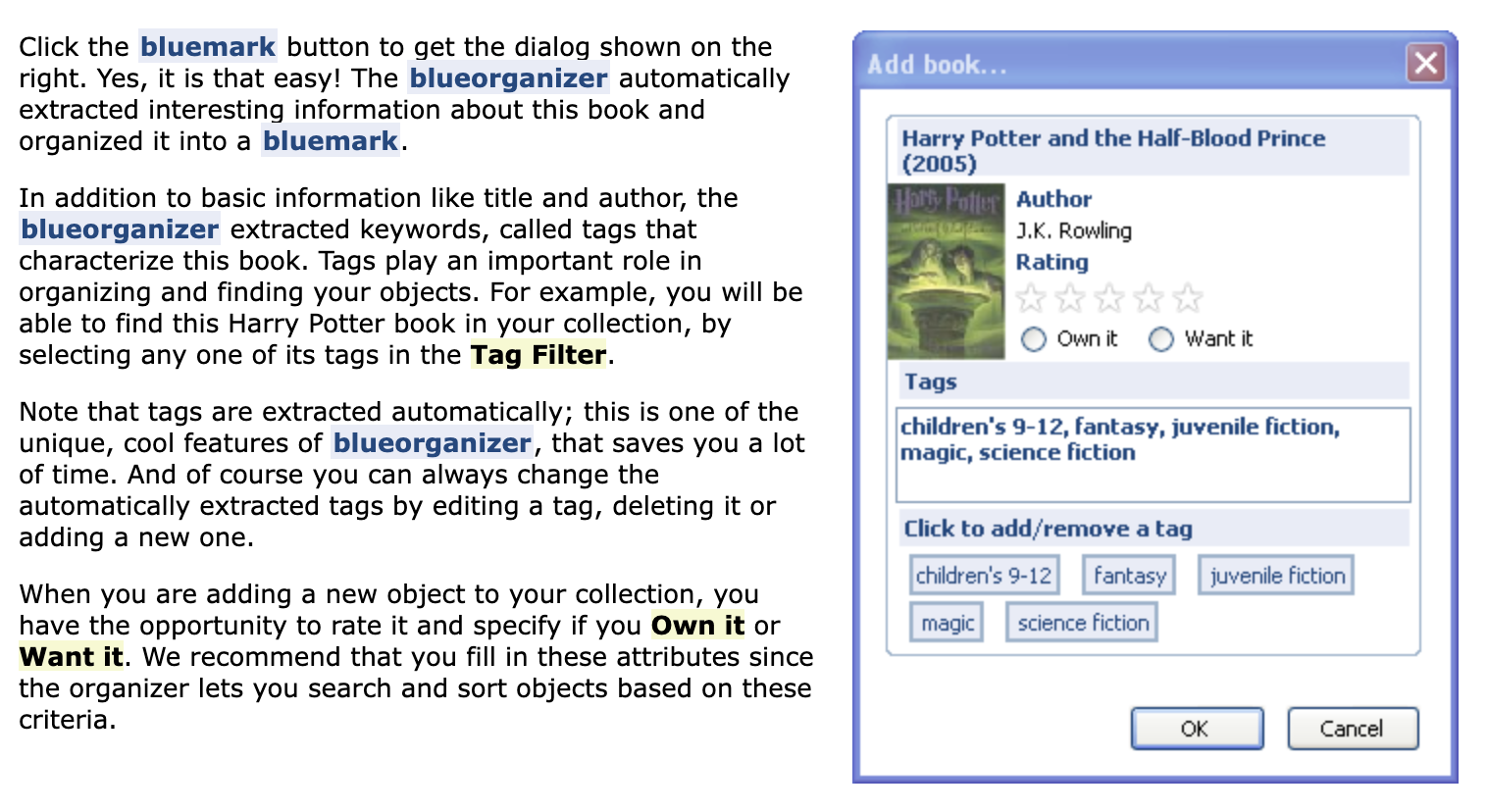

Alex Iskold was a native Ukrainian whose family had moved to the United States in the early 1990s. He was about my age, but on arrival he didn’t speak English, and so he attended a community college at first. He then studied computer science at New York University and became a software engineer for Goldman Sachs in mid-1994 (the exact same time I started my first job, in Auckland). Alex was onto his second startup by the time he contacted me in May 2006. His company was called AdaptiveBlue and had built a Firefox extension called Blueorganizer, which allowed people to “automatically collect, tag and share objects such as books, music albums and movies,” as it was described to me in the first email pitch I received.

Blueorganizer in action.

Alex emailed me several more times, requesting that I write a review of Blueorganizer. He was very persistent and kept following up on my empty promises to “look into it soon.” During one of these email exchanges in August, he offered to write articles for me. One of his ideas was a post about the “new breed of smart client applications built on top of virtual web services like Amazon.” I was intrigued with that idea, since Amazon had just released its first cloud computing product that March. Called Amazon S3, it was a cloud-storage solution and I’d blogged about it on ZDNet. But I hadn’t yet found a way to discuss it on RWW, which had more of a consumer web focus. Also, given Alex’s background as an engineer, I figured he’d be great at explaining the technical implications of what Amazon was up to with its new “web services” infrastructure products. The term cloud computing wasn’t yet popular, so tech bloggers like me were still trying to figure out Amazon’s strategy.

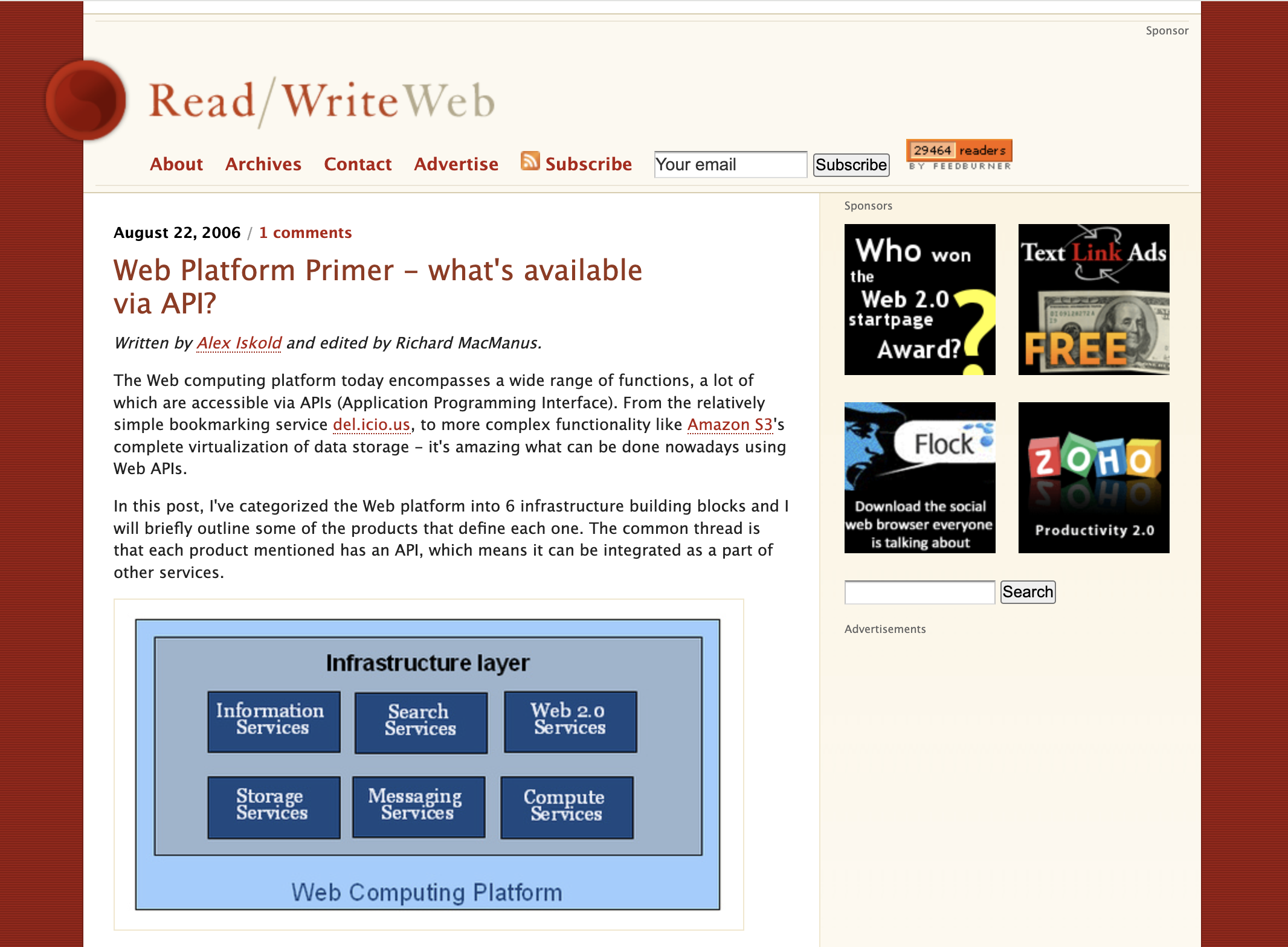

A couple of days later, Alex sent me his draft article, which he’d titled “The Emergence of the Web Services.” The article was a very smart analysis of what Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and the like were building in the infrastructure layer of the web. He even had a graphic that neatly encapsulated the types of web services these companies were creating—“storage services” (such as S3), “messaging services,” “compute services,” and so on. Because English wasn’t Alex’s native tongue, there was a fair bit of editing to do—but it was clear to me that the content was top quality. I renamed the article “Web Platform Primer—What’s Available via API?” and published it on August 22, 2006.

Alex Iskold’s first RWW post, August 2006.

Because Alex was building a startup that utilized the new web platform services from Amazon and others, he was able to see the bigger trend emerging. As he put it in the article, “10 years of Amazon’s expertise in large-scale distributed computing are suddenly available at a very reasonable cost to anyone who is paying attention.” I immediately recognized that Alex’s technical posts about the web platform would be the ideal complement to my own posts. Also, he was amenable to my edits. I had changed his opening to make it less abstract and more practical for web developers. Some people may have objected to this type of editing, but Alex wanted to fit in with the existing RWW style. “I see what you are looking for—clean, simple and factual style,” he wrote back after seeing the published article. “I have no problems doing things this way.”

Just a couple of days later, Amazon released the second product in its new cloud computing suite. Called Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2), it fit perfectly into the “compute services” section of Alex’s post. Alex had written that there were “no generic examples of black-box compute services that are available today on the web via API,” but Amazon’s EC2 seemed like it had been released just to fill that void. I wrote up a quick post about the news, noting that the name “sounds like a Terry Gilliam movie” and then pointed readers to Alex’s post: “he really captures the high level of why products like Amazon EC2 are increasingly important in today’s Web landscape.”

In August 2006, Amazon unleashed cloud computing onto the world.

This was the birth of what we now know as Amazon Web Services, which eventually got spun off by Amazon and became almost the most successful company to emerge out of Web 2.0—behind only Facebook. I’m proud that RWW was one of the first blogs to write about Amazon’s web services, and one of the few to identify its massive potential. I have Alex to thank for that.

Alex’s next post was a survey of the client apps using the new web platform, which gave him a chance to mention Blueorganizer and its use of the S3 storage service. I was okay with this type of subtle self-promotion, which became a common tactic used by future contributors to RWW. As long as it was disclosed in the post and didn’t detract from the analysis of web technology—RWW’s core focus—I didn’t mind if a contributor slipped in the odd mention of their product.

Emre’s GoogleOS post was one of the most popular of the year. Note also the new and improved RWW logo!

RWW had several other regular contributors by the end of 2006, but the other one to have a significant impact in the years to come was Emre Sokullu, a young Turkish entrepreneur. Like Alex, Emre was a clever software engineer, and I valued his technical expertise when writing posts such as “GoogleOS: What To Expect” and “Search 2.0—What’s Next?” Those posts generated a lot of discussion on the site, along with page views, and helped solidify RWW’s growing reputation as the “thinking person’s tech blog.”

Lead image: Me and Alex Iskold, a few years after he began writing for Read/WriteWeb; photo by Mike Dunn

This post is part of my serialized book, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley’s Web 2.0 Revolution. View table of contents.

Next up: 019. Lou Reed and the Web 2.0 Summit

You're reading Cybercultural, an internet history newsletter. Subscribe for free, or purchase a premium subscription. Your support for this indie publication would be greatly appreciated.