Visiting the Microsoft Campus in Redmond; January 2006

It's January 2006 and I attend Microsoft Search Champs to discuss Live.com, the company's start page. I also catch up with a fellow Web 2.0 Workgroup member.

It was a cold but sunny Wednesday morning and a Microsoft charter bus pulled into a complex of red brick office buildings, all no more than three stories high. This was Microsoft’s headquarters in Redmond, located about twenty minutes’ drive from downtown Seattle.

The two days of Search Champs would be held in Building 31. I didn’t know how this area of the campus compared to the others, but what I saw was an unexpected blend of office and nature. Green and red shrubbery lined the buildings, and evergreen Douglas fir trees dotted the exterior. It was the middle of winter, so the smaller deciduous trees inside the campus were bare; their reddish-brown branches appearing to blend in with the neatly patterned brick of the buildings.

Compared to the bright yellow and purple themed Yahoo campus, with its gleaming concrete and glass offices and artificially neat lawns, the Microsoft campus seemed calmer and more attuned to the surrounding nature. Perhaps that was simply because it was a decade or two older than the Yahoo offices, and so nature had had more time to come to terms with the encroachment of technology.

The Microsoft campus in Redmond, January 2006. Photo by me.

At the time I visited, in January 2006, Microsoft was on the cusp of another growth spurt. The company employed 28,000 people in the Seattle area and its Redmond campus was about 8 million square feet. Just a month after I visited, the company announced plans to add another 3.1 million square feet onto the campus over the next three years — enough room for 12,000 more people.

Microsoft’s corporate software was the main reason for its growth, but it was also keen to capitalize on the consumer web trend known as “Web 2.0” — especially since its Internet Explorer web browser still held around 90% market share. Just as Yahoo had begun to actively court tech bloggers like me (it was why I’d been invited to its campus several months ago), Microsoft also saw bloggers as a way to help promote its online services. It even had its own resident bloggers, most prominently Robert Scoble. I’d come across Scoble a few years prior — he was one of the first well-known bloggers to link to me. In July of 2005, he conducted a video interview with then Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer, who told Scoble that he saw blogs as “a great way to have customer communications.”

Robert Scoble’s interview with Steve Ballmer, July 2005.

Of course, as with nearly every category of software, at first Microsoft thought it could conquer blogging. At the end of 2004, the company released its own blogging software, MSN Spaces, and inter-linked it with its existing communications software, Messenger and Hotmail. However, Microsoft quickly discovered that bloggers were far too independent-minded to use its product. Even the political bloggers avoided MSN Spaces, preferring to stick with specialized blogging software like Movable Type (which I used) and the emerging WordPress. Eventually, Microsoft realised that it could simply entice tech bloggers onto its actual turf — in Redmond — and try to influence them that way.

We filed out of the bus and entered Building 31. The reception area had pale yellow walls with wood paneling, and a brown patterned carpet. There was a large potted tree in the middle of the room and next to it was a foosball table, with red and black characters. The front of the table had a Windows.NET sticker on it, which someone had unsuccessfully tried to peel off — perhaps an over-zealous manager, or maybe a contractor had decided the sticker wasn’t cool enough for a foosball table? Regardless, we continued upstairs and were led into a nondescript conference room

Brady Forrest, a Program Manager at Microsoft, began talking about the agenda for today and tomorrow. He was a confident-looking guy with styled brown hair and a goatee, dressed in a burgundy dress shirt and blue jeans. He explained that after opening presentations from a couple of Vice-Presidents (I still didn’t understand why American companies had so many Vice-Presidents), we would go to breakout sessions with our assigned product groups. Fred, Mike, Josh and I had been placed in the “Live.com” track of Search Champs.

Brady Forrest outlines the Search Champs agenda (I’m standing on the side, next to Mike Arrington); photo by Michael Casey.

Live.com was Microsoft’s entry into an emerging product category known as a “start page.” Part old-style internet portal with news and interactive media (like MSN), part digital dashboard, and part RSS Reader, the idea of a start page was that it would be a user’s home page when they started up their browsers. Indeed, Microsoft’s version was originally called start.com, which evoked memories of The Rolling Stones singing “Start me up” in its famous Windows 95 tv commercial. Start.com was a better name than live.com, but the latter was part of Microsoft’s new “Windows Live” branding for all its internet software (where “live” indicated online).

The face of Microsoft’s Live.com was Sanaz Ahari, a Persian-American woman who had created it at age 23. Perhaps because of her youth, she wasn’t our track leader. But she was clearly the person who had the most knowledge about it. With her long black hair tied back and wearing a straight-forward black tee-shirt and jacket over blue jeans, Ahari was a focused presenter at Search Champs. She was nervous, but who wouldn’t be at that age — also, it must be said, presenting to a group of mostly male geeks. In our track of ten tech bloggers, there were just two women: Dori Smith and Gina Trapani. It was about the same in the other tracks.

What Ahari was most excited about was the ability for users to add interactive “gadgets” to live.com — basically mini web applications that you could easily access on this one web page. It was common at the time to have a weather forecast app and a calendar app, as well as various email and note-taking apps. Start pages were seen as a greenfield environment for Web 2.0, because the hope was that the companies that hosted them would offer open access for web app developers.

A version of Live.com from early June 2006; the product evolved rapidly…and not always in ways that made sense.

One of the new things Ahari showed off to the assembled bloggers was a TV recommendations gadget, which she promised would be released soon. It enabled you to control your Windows Media Center box remotely, for example to record an upcoming tv show (remember, this was years before streaming tv). This kind of app was typically built using Ajax, the web development technique that had come to dominate Web 2.0 after the release of Gmail in 2004. Ajax (“Asynchronous JavaScript and XML”) allowed web apps to send and retrieve data from a server in the background, making web pages much more interactive than they’d been in the Dot Com era. Sometimes, start pages were referred to as “Ajax homepages” because of its influence.

Microsoft’s overall Web 2.0 strategy was a familiar one: “embrace and extend” — it wanted to integrate its web products into the Windows software environment. The company had been barred from integrating its dominant browser, Internet Explorer, into Windows (the US Justice Department had won a famous antitrust trial against Microsoft in 2001). But they didn’t face the same restrictions with browser-based applications. So live.com was pitched to us that day as a “desktop on the web”; where gadgets could be dragged and dropped between the user’s browser and Windows desktop.

A RWW post during Search Champs; via Wayback Machine

The emergence of smartphone apps a couple of years later put paid to the start page concept — nowadays, the live.com domain name redirects to the online version of Outlook. But in early 2006, start pages were one of the hottest areas of Web 2.0 development. So were APIs (application programming interfaces), which a new friend of mine had managed to turn into a compelling blog topic.

During the first day at Search Champs, I met fellow tech blogger John Musser for the first time. He was in the “developer” track, but we got a chance to chat in the breaks.

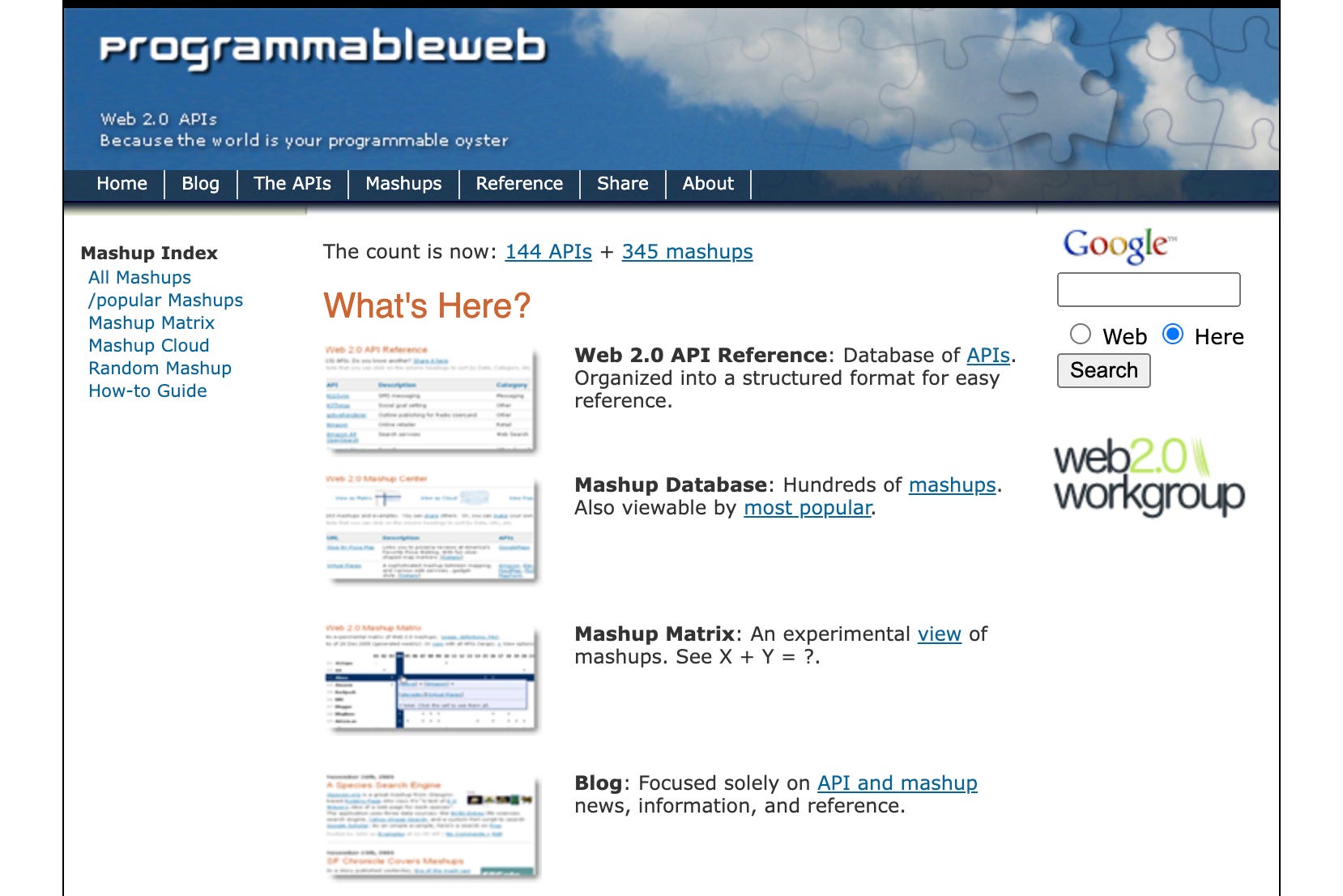

Originally from NYC, John now lived in Seattle and ran a blog and online resource called ProgrammableWeb. The site documented and commented on Web 2.0 APIs, which were fast becoming the default way developers integrated third-party web services into their applications. For instance, you could embed MSN Messenger into your website or blog using a Microsoft API. APIs also powered so-called “mashups,” where two web services were melded together to form a new application; the best example at the time was HousingMaps, which plotted Craigslist real estate listings onto Google Maps.

John had started his website in August last year and in October he’d contacted me to ask if it could be included in the Web 2.0 Workgroup. He said he would contribute a “programmer’s-eye-view of the Web 2.0 API landscape” to the group, along with “a very dry sense of humor.” Mike, Fred and I quickly agreed to add him, and soon we began swapping emails.

ProgrammableWeb, January 2006; via Wayback machine

In person, John was lean with short-cropped black hair (slightly greying) and he wore a pair of small oval glasses. He was 44 when I met him, so a decade older than me. He seemed more British than American, with his polite demeanor and the dry sense of humor he’d promised. We got on just as well in person as we did online.

Unbeknownst to John or me at the time, we had become embroiled in an internal O’Reilly Media tug of war over a book about Web 2.0. In December, John had emailed me to say that he’d been contacted by O’Reilly Media to write an introductory book about the subject. He’d quickly whipped up a proposal, not knowing that Josh Porter and I were already working on a Web 2.0 book. When John’s contact at O’Reilly Media discovered that our project would cover the same territory, his proposed book was put on ice. John was disappointed, but graciously accepted that Josh and I were already well into our project.

During the breaks at Microsoft Search Champs, John and I chatted about the O’Reilly book situation. We agreed it was a case of crossed wires.

It was only a few days later, after Search Champs had finished and as I was midway through my journey back to New Zealand, that I discovered that O’Reilly was still keen on bringing John on. On the stopover at Sydney, I opened my email and saw a message from our O’Reilly editor with the subject line, “John Musser.” It was addressed to me and Josh, and cc’ed the editor who had approached John. The email asked, would we mind if John became a co-author? I was about to board my connecting flight, but I quickly wrote back to Josh that I wanted to say no. We both liked and respected John a lot, but I didn’t want to change our outline or writing plan. After I got back home, I found that Josh agreed with me and had spoken to our main contact at O’Reilly to nix the idea.

We thought that was the end of it, but over February communications with our assigned editor began to dry up. We suspected something was up, so at the start of March we emailed to ask for a status update. The reply came later that day: our book had been cancelled and O’Reilly was now “exploring other avenues toward completing this project.” We were naturally very disappointed, as well as frustrated about the lack of recent communication or feedback from our editor.

I couldn’t help but wonder if O’Reilly had asked John to take over our book. I emailed him about it straight away. He said that he was still in discussions with O’Reilly about doing something with them but didn’t yet have a deal.

The O’Reilly Web 2.0 book eventually turned into a 100-page report released later that year, in November 2006, entitled “Web 2.0: Principles and Best Practices.” It was written by John based on Tim O’Reilly’s ideas. It was very different to the more design-focused book that Josh and I had been working on; in his announcement post, John noted that the report was being marketed to a business audience and “you won’t find it sold in bookstores.”

I never had any hard feelings with John about this. We were both figuring out how to run a professional blog business at the time, so we continued to keep in touch and regularly swapped notes over 2006 and into the future. I put all the blame on our failed book project with O’Reilly Media. Even our main contact at O’Reilly had admitted that “we failed you, quite simply.” It wasn’t much consolation to Josh or me at the time, but we both chalked it up as a learning experience.

John Musser and me in June 2006; photo by Dan Farber.

Looking back on it now, the book project back and forth encapsulated something about “Web 2.0” that I had an inkling of at the time, but that I had repeatedly tried to shrug off. Which was that Web 2.0, the trend everyone was so excited about and that was driving the new internet economy, was an amorphous concept. Nobody knew what it meant — even Tim O’Reilly, whose definition of “what is Web 2.0” seemed to expand every month. In my blog, I’d kicked back against the hype a few times, but the reality was I was riding the wave just as much as O’Reilly was.

As for Microsoft, it simply wanted to latch onto the new, new thing — whatever it was at any one time — and assimilate it into their Windows world. As part of this strategy, Microsoft had correctly identified tech bloggers like John, Josh, Mike and I as the carriers of the latest technocultural meme. We were happy to oblige, because we understood that infecting Microsoft with our meme would help bring our niche blogs to a newer, more mainstream, audience.

This post is part of my serialized book, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley’s Web 2.0 Revolution. View table of contents.

Next up: 014. Reluctant Salesman

You're reading Cybercultural, an internet history newsletter. Subscribe for free, or purchase a premium subscription. Your support for this indie publication would be greatly appreciated.