Revving Up at the 2005 Web 2.0 Conference

Day one of the 2005 Web 2.0 Conference, held at the Argent Hotel in San Francisco; including a meeting with the man himself, Tim O'Reilly.

The Web 2.0 Conference kicked off on Wednesday, October 5, 2005, at The Argent Hotel on Third Street in San Francisco. I’d gone into the city on the Caltrain earlier in the week, to take in the sights of Haight St and familiarize myself with the Union Square area. But today would be my first experience of a tech event in America.

Since I wanted to arrive early on the first day of the conference, I’d arranged to catch a lift into the city with Keith Teare, Mike Arrington’s business partner. Mike was more relaxed about the event and he had posts to write, he told me, so he would arrive later.

Keith was a balding 51-year old Englishman who had a long history of running startups — he’d co-founded a London ISP and Internet cafe in the 1990s, then moved his family to Palo Alto in 1997 and founded a domain name service called RealNames. That company hired Mike, as a lawyer, in 1999.

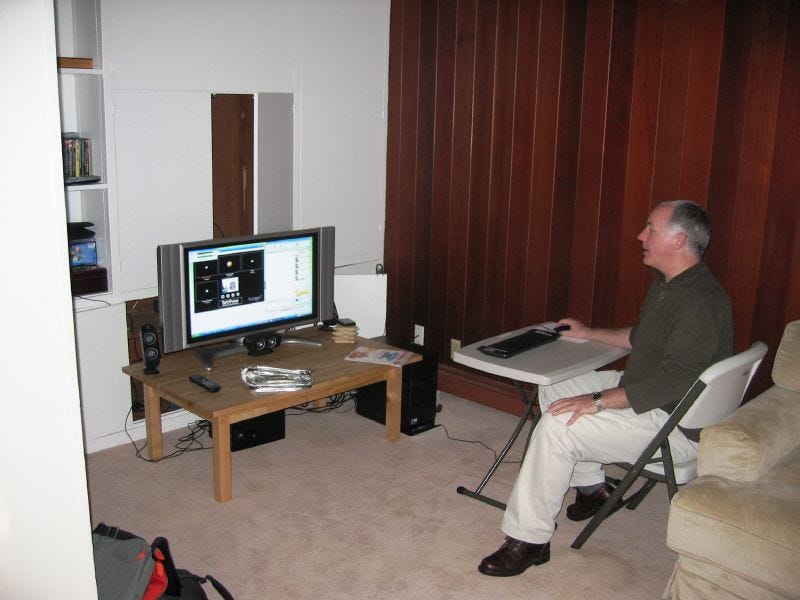

During my stay at Mike’s house, Keith would drop by regularly. He always seemed business-like and even a little stern. He had firm opinions on startups and business strategy, which I took note of but didn’t engage him in conversation about — perhaps I was intimidated by his industry experience. He usually dressed like how I imagined a VC would, in tan slacks and business shirt. I didn’t get close to him, like I did with Mike, Gabe and Fred. Partly that’s because I only saw him occasionally, but there was also a generation gap between us (ironically I’m the same age now, as I write this, as he was in 2005 — and so I have more sympathy for his character now).

Keith Teare in Mike’s living room in October 2005; photo by Michael Arrington.

A few months before I’d arrived, Keith and Mike had formed an incubator company called Archimedes Ventures. Although TechCrunch was technically a project of this company, Keith was much more focused on edgeio, their nascent startup that aimed to be a classifieds site for the Web 2.0 era. As the senior partner and a self-described “seasoned entrepreneur,” Keith seemed concerned about how much time Mike was spending on TechCrunch. I would sometimes hear the two bickering over it. Even I could understand Keith’s attitude towards blogging, though — it didn’t seem like a proper business at that point. It was more like a hobby, allowing us to test new web products and meet like-minded people.

The Argent Hotel was a 36-story building around the corner from Market St, in the center of San Francisco. As we walked in, I could see that was an impressive building — with stone flooring, wooden panels, and a gold and mustard colored decor. The yellow-patterned carpet and wallpaper was beginning to fade, however, probably because it dated back to the mid-1980s when the building had been constructed. Alongside the gold leaf domes and chandeliers inside the main lounges, the overall impression of this hotel was of a somewhat tired opulence. It seemed more like a space for investment bankers to convene for a conference, rather than internet entrepreneurs.

Web 2.0 Conference 2005; photo by Gen Kanai.

But then I remembered that money was indeed top of mind for many of the Web 2.0 Conference participants. In July, MySpace — the biggest social network on the internet — had been acquired by News Corp for a reported $580 million. That event kick-started the internet economy, making Web 2.0 not just a new web era, but a new speculative market too. The race was on to build social software applications across a range of different “verticals.” YouTube had launched its beta in May, Reddit launched in June, and of course Marc Andreessen’s Ning launched the night before the Web 2.0 Conference. These startups, and many more, were reaching for the shiny new brass ring that Tim O’Reilly’s company had named “Web 2.0.”

In addition to Ning, there were a couple of other acquisitions the night before the conference started. First, Yahoo! bought upcoming.org, an events service created by a tech blogger named Andy Baio. There had also been action in the RSS Reader market, with Newsgator acquiring one of its competitors, NetNewsWire (it had been an eventful year for RSS Readers — my personal favorite, Bloglines, had been acquired by Ask Jeeves in February). The excitement generated by this business activity was palpable on day one of the Web 2.0 Conference. There was an audible buzz in the air, as hundreds of entrepreneurs, VCs and bloggers talked startups, network effects, mashups, and other Web 2.0 theories.

Conference website just before the event began.

As soon as I claimed my press pass at the registration desk, I headed upstairs to the second floor for the morning workshops. It turned out that all the rooms were tiny, which meant it was standing room only no matter which workshop you attended. If, that is, you could even get in — there were guards posted at the entrances, who barred people from entering if it was too full.

Somehow I squeezed into one of the workshops and stood at the back, my laptop bag being pressed into my side as others jostled for position. I spotted the only other New Zealander I knew of at the event, Nat Torkington — who worked for the conference organizers, O’Reilly Media. Nat was about my age and had lived in the US since the late 1990s, after marrying an American. We had gone to the same university in Wellington, at around the same time, but I’d not met him in person until today. Nat was an outgoing guy and a natural in-person communicator, traits that I unfortunately lacked. He made me feel welcome — “great to see another kiwi here,” he yelled at me over the hubbub of the crowded workshop.

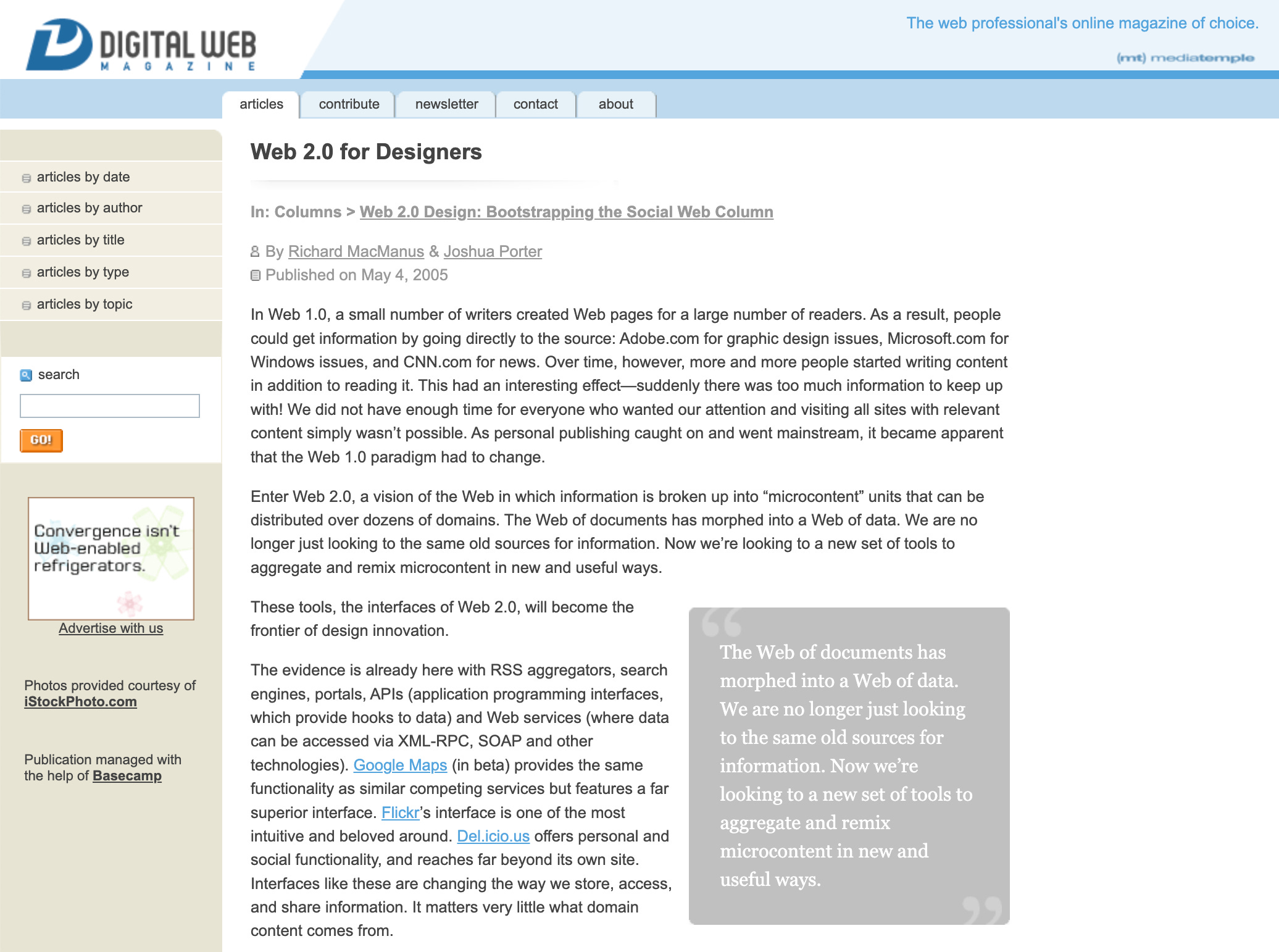

I had several contacts I was keen to meet in person at the event. One was Joshua Porter, who I’d recently co-signed a book deal with for O’Reilly Media. He was a 27-year old web designer from Newburyport, Massachusetts, who wrote a blog called Bokardo. We’d begun emailing near the end of 2004, and soon developed a good rapport. In May 2005, we co-authored an article for the web design magazine Digital Web, entitled “Web 2.0 for Designers.” Nat Torkington read the article and linked to it in O’Reilly Radar, his company’s blog. This attracted the attention of the man himself, Tim O’Reilly, which prompted an O’Reilly Media executive to email me and ask if we wanted to turn our article into a book.

The May 2005 article that led to a book deal with O’Reilly Media.

Excited by this development, Josh and I wrote a book proposal and eventually signed a contract at the end of August 2005, which included an advance of $10,000 between us (to be paid over four instalments). We’d delivered the first two chapters of the book just before the conference and would be meeting Tim sometime during the event to discuss the project.

I ended up meeting Josh in-between sessions on that first morning. He had rimless glasses, close-cropped brown hair, and was dressed casually in a red sweatshirt, sneakers and blue jeans. He had a nervous, innocent air about him and I realised that while I was naïve about the tech industry, in Josh I’d met someone who was even less experienced than me.

When Josh and I eventually got called up to see Tim, we made our way upstairs through the crowd and were hustled us into a make-shift meeting room. Tim was talking to someone at the back of the room, so tentatively we walked over.

Tim O’Reilly at the Web 2.0 Conference 2005; photo by Peter Kaminski.

Tim was 51 years old at this time (the exact same age as me as I write this, in 2022). He wore a custom made silver-blue suit with the same sky blue button up shirt that all the VCs wore over here. His brown hair was thinning and greying at the sides and he had a long chin that accentuated his clean-shaven face. His eyes were the same pale blue color as mine — no doubt we shared a similar Irish ancestry. As Josh and I approached, the person he was chatting to peeled away (probably an employee) and he focused his enquiring, slightly skeptical gaze upon us.

I think Tim was curious about who I was, this nobody from New Zealand who had become one of the most popular bloggers about his own theory — Web 2.0. He scanned me with his arched eyes, the sides of his mouth creasing into a familiar smirk. It was the expression of a self-made businessman, someone who was among the pioneers of the commercial web and who knew it. He didn’t seem impressed by me, and why would he be? I was dressed poorly, in a pair of blue jeans and a brown-colored dress shirt (I didn’t even own a proper jacket at that point). And I was nervous about meeting him. Even though I’d interviewed him over Skype last November, I didn’t feel like I had established a meaningful rapport with him at that time.

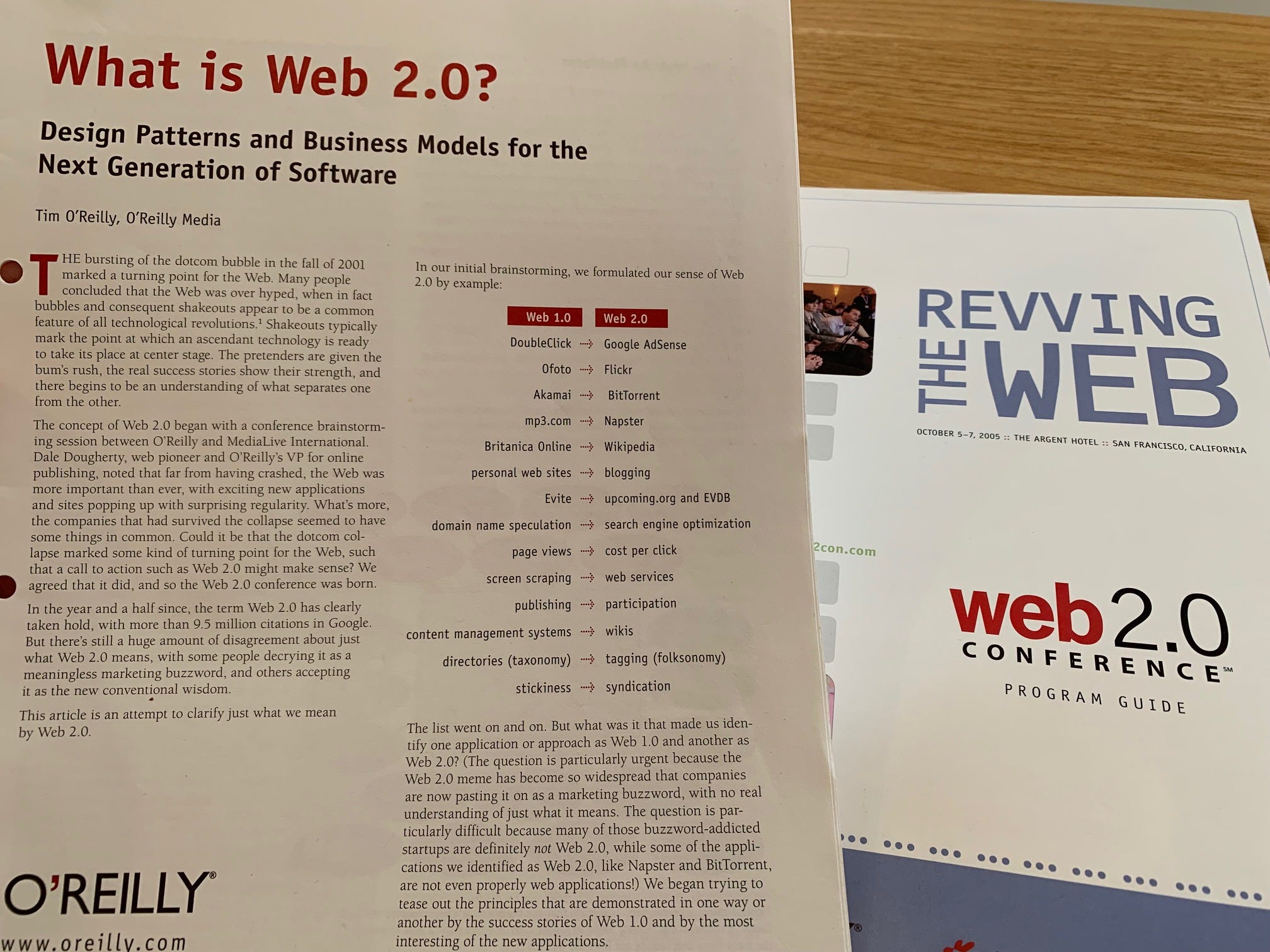

The awkward pleasantries finished, Tim began talking about what he wanted our book to be. In his Southern California drawl, which always seemed to my ears to have an overlay of condescension, he went over the highlights of his pre-conference article, “What Is Web 2.0: Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation of Software.” The 5-page article was the first time he had attempted to define Web 2.0 (this was an era when long articles were spread over different pages, partly to get more page views). He wanted our book to flesh out the “design patterns” that he had established. We simply nodded in response, as it had become clear that our input wasn’t required during this meeting.

Along with the official program guide, attendees received a copy of Tim O’Reilly’s “What is Web 2.0?” essay.

One of Tim’s design patterns was “Data is the Next Intel Inside,” which was a phrase that he used in all his conference talks and during most interviews he did too. Just as Intel’s microchip was the core ingredient in almost all PCs during the 1990s and into the 2000s — and was branded as such, with a sticker on the front of the PC bearing the slogan “Intel Inside” — the key ingredient of a Web 2.0 service would be its database. Like the microchip, custom data would power services like Google and Amazon — so Tim’s theory went — and would form the foundation of what he called the “internet operating system.”

It was all heady stuff and Tim clearly had set ideas on what Web 2.0 should mean and how our book would help explain it to web designers and developers. It didn’t seem to matter to him what new ideas we might bring to the table, and before we knew it, he was talking about some online publishing experiments the company might try out with our project. The words “the long snout” came out of his mouth, a phrase he repeated several times — it appeared to mean a possible new kind of wiki publishing arrangement, to complement the actual book. (A few months later, Tim would publish an article propounding on his “long snout” theory, which had something to do with using the internet to publish early and often. I’ll be honest, I still don’t know what it means to this day.)

Before we knew it, Josh and I had been shuffled out the door so that Tim could prepare for the next talk he’d be giving on-stage. Back outside, amidst the hubbub of the conference hall, we looked at each other quizzically. If anything, we were now even less sure about what our book was about, but there was plenty of time to sort through the details when we got back to our respective homes. For now, we each had a workshop we wanted to attend, so we parted ways.

Lead image: My press badge for the Web 2.0 Conference, October 2005.

This post is part of my serialized book, Bubble Blog: From Outsider to Insider in Silicon Valley’s Web 2.0 Revolution. View table of contents.

Next up: 007. Day 2 of the 2005 Web 2.0 Conference

You're reading Cybercultural, an internet history newsletter. Subscribe for free, or purchase a premium subscription. Your support for this indie publication would be greatly appreciated.