Why Marc Andreessen is a Key Character in My Book

by Richard MacManusI explain how Marc Andreessen was a much bigger part of my original outline, and show you an 'outtake' I wrote about his 2004 activities.

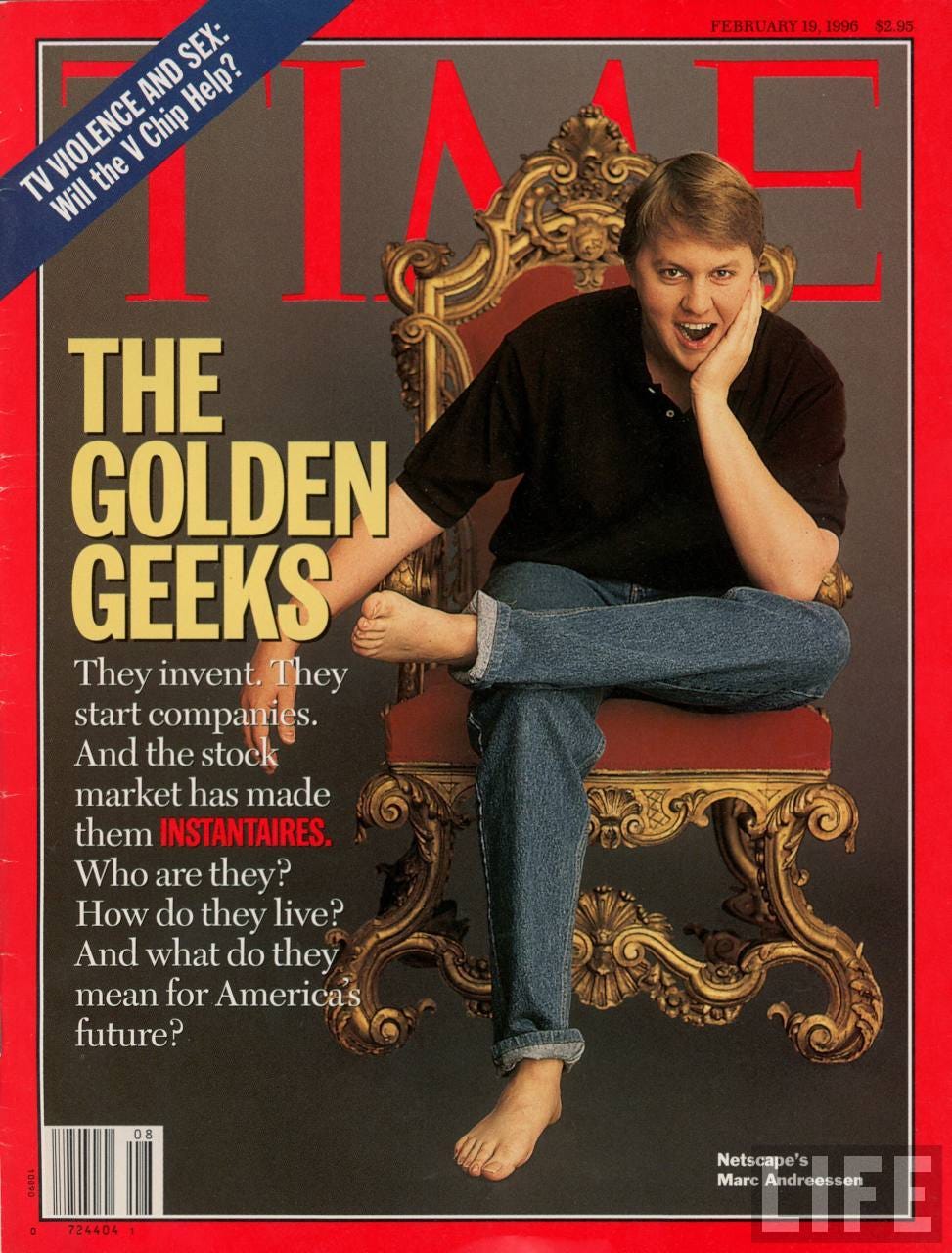

Marc Andreessen, bare feet and all, on the cover of TIME magazine in Feb 1996.

When I was planning the book that turned into Bubble Blog, Marc Andreessen was to be one of the main characters. He and I are the same age, so I thought it’d be a neat idea to track my career alongside his. How cool would it be to have the Ultimate Insider’s narrative threaded through my own Outsider narrative? I even had a book title lined up: “Eating the World” (in reference to Andreessen’s influential 2011 essay, Why Software Is Eating the World).

I began writing the book with this plan in mind, but I soon discovered that actually my own story was enough to propel the narrative — that the book should be a straight memoir plus internet history. I labeled the revised book plan a “Web 2.0 memoir”, a term I continue to use today to describe Bubble Blog. So I largely abandoned the Andreessen narrative, although I did fold bits of it more subtly into my own story (since I still think he’s the perfect insider foil to my outsider main character).

Anyway, I thought a good bonus post for paid subscribers would be to show you part of what I originally wrote, when Andreessen was a bigger part of my outline.

A bit of context… The following extract originally came after the section in which I described my interview with Marc Canter in 2004 (which you can read in 003. The First Web 2.0 Conference.) It basically describes what Andreessen was doing in 2004 and it includes a short history of his career up till that point. You may also notice that I re-used pieces for what became Bubble Blog, so apologies in advance for any repitition. Also, the extract below is very draft 1 material, so it’s not as polished as the final book!

Marc Andreessen in 2004

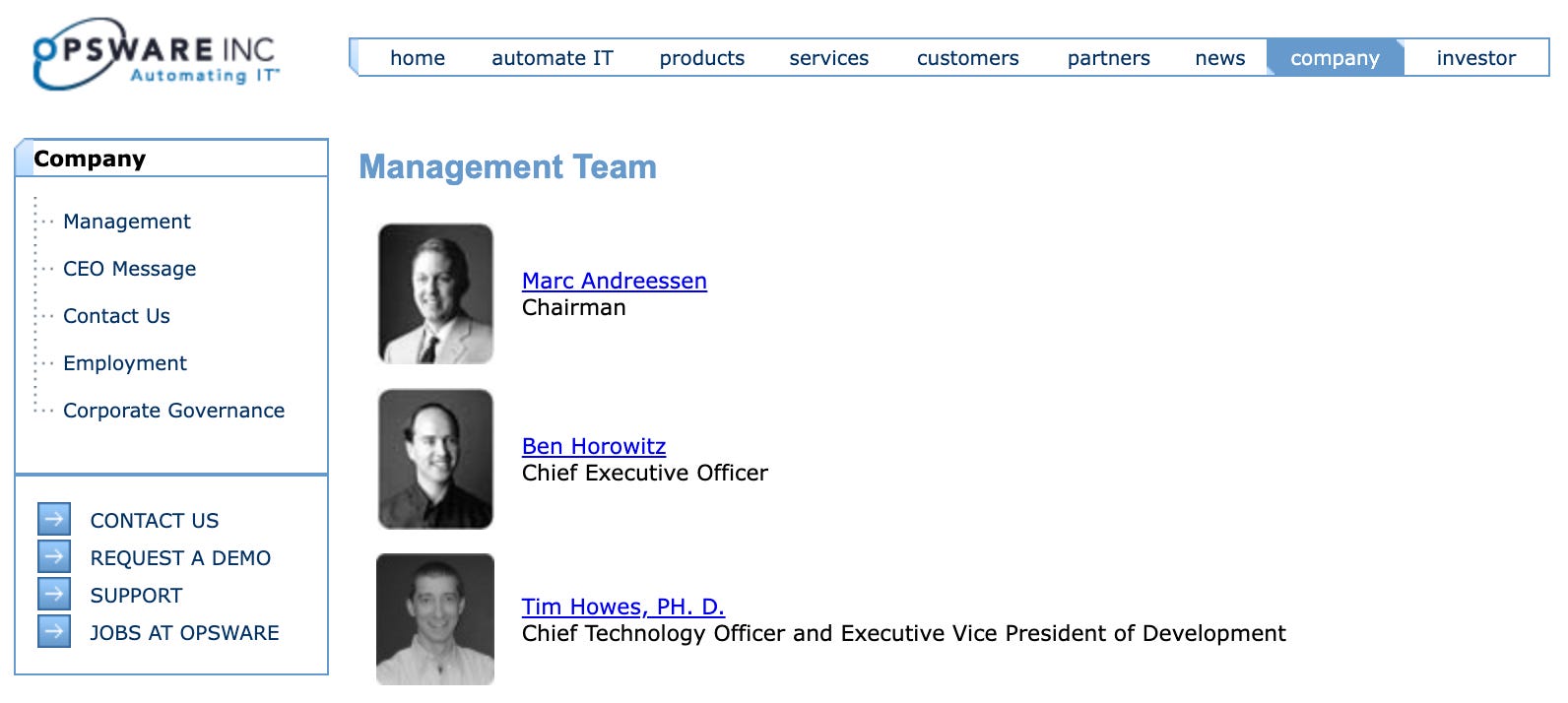

The other Marc, Andreessen, was doing just fine financially and had no shortage of attention, but he too was trying to adapt to the new era. He began 2004 as Chairman of Opsware, the business software company he’d co-founded with Ben Horowitz (who he eventually went into the VC world with). In an interview he did with the San Francisco Chronicle at the end of 2003, he talked about the recession caused by the Dot Com bust — which at the time was still playing out. “History suggests that recessions are good times for the next big things to emerge,” he said, “although they’re never viewed as such at the time.”

Andreessen in November 2003; photo credit: The Chronicle

If social software was on Andreessen’s mind at the start of 2004, he wasn’t telling the media. He would only say that “there’s going to be growth in a whole bunch of digital industries,” but his examples were generic (“digital photography, digital music, digital video, digital gadgets and gizmos”). Ultimately, he was doing this interview to talk the book of his current company, Opsware, so he gently steered the conversation into business topics (“the server hardware landscape is commoditizing”), before the reporters steered it back to Netscape anecdotes.

Andreessen was just 32 years old at the time and even though he looked the part — a photo from 2004 shows him in a white-and-brown checkered business shirt and a light brown suit that looked like something a much older man would wear — his face was as young and his cheeks as rosy as mine were at the same time (again, we’re almost exactly the same age). But his hairline was already receding and his eyes looked anxious and had slight bags under them, suggesting that his life up till then had had more pressure in it than mine. Or maybe he was feeling the strain of being a corporate IT executive and just wanted a change.

Despite his youth, he was mature enough to recognise his own strengths and weaknesses. He admitted to the Chronicle that he didn’t have the temperament for operational roles. That was partly why he and Opsware CEO Ben Horowitz complemented each other so well, then and into the VC future. It also explained why he’d gotten restless. There had to be more to Silicon Valley life than reminiscing to the media about the 90s while trying to market his business software company.

What was going through Andreessen’s head in the summer of 2004, when he decided to start a new company? This would be his third startup, after Netscape and then Opsware (which he would remain chairman of until it got acquired in 2007). He’d co-founded two incredibly successful companies and was a millionaire many times over. Yet he’d only been in the commercial world for a decade!

Ten years ago to the day, he’d been just a few months into a new startup venture with Jim Clark, called Mosaic Communications. The pair had set up shop in a tiny office in Mountain View and, along with a group of Andreessen’s ex-NCSA fellow students that they’d hired, were attempting to build a “Mosaic killer” — a clone of the NCSA version of the Mosaic browser. They had no idea how this venture would make money. In a message he sent to a newsgroup in May 1994, Andreessen talked about offering a “cyberspace mall” service, “to support hypermedia information distribution and interactive transactions” for companies that leased space on their server.

Netscape officers Jim Barksdale, Marc Andreessen, and James Clark, 1995; Credit: Encyclopædia Britannica

Mosaic Communications, which soon became Netscape, never did figure out how to make money — its server business was quickly kneecapped by Microsoft and they couldn’t charge money for their browser, since Microsoft’s browser was free. Even though Netscape went on to have a hugely profitable IPO and sold to AOL for billions, there was a lingering sense that it never reached its commercial potential.

His second company had been a different beast. It had started out as LoudCloud in 1999 at the height of Dot Com mania, IPO’ed in 2001, then had a rocky couple of years and almost went bankrupt, before morphing into Opsware in 2002 and turning the corner. By 2004, Opsware still hadn’t made a profit, but it was now a solid software-as-a-service business and the stock market believed in it. There wasn’t much left in the way of excitement for Andreessen, though, since further growth was more reliant on the operations side of the business than in product innovation. Sure, he could just chew the cud and continue to live comfortably off his chairman’s salary, but he wasn’t ready to be put out to pasture — not at age 32. He didn’t want to spend the next few years grazing in the Opsware server farm, like a prize bull whose time of siring startups had come to an end.

Chairman of the board; Opsware in April 2004

The internet was still young, and so was Andreessen. He sensed there was another sea change happening on the web and he wanted to be a part of it. He’d heard all the buzzwords being bandied about in 2004 within Silicon Valley by the young founders he socialised with — social software, social networking, user-generated content, blogging, wikis. He had dabbled in angel investing already; and indeed would invest in his friend Reid Hoffman’s company, LinkedIn, later that year. One option, then, was to use all of his connections and capital, and become a VC. But no, he decided it wasn’t time for that yet. He still wanted to be in the arena, as Theodore Roosevelt had once famously put it. (Roosevelt’s quote — “It is not the critic who counts […] The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena…” — has since become a Silicon Valley maxim and was the subject of a 2007 Techcrunch post by Mike Arrington).

Andreessen’s third act came to be called Ning and when he started it in July 2004, he chose a 32-year old Stanford alumni named Gina Bianchini to be CEO.

Christian Witkin’s photo of Gina Bianchini and Marc Andreessen in a 2008 Vanity Fair profile; via Boing Boing

If Andreessen became a Silicon Valley insider by dint of his outsized success at Netscape, Bianchini was one by birth. She was a Silicon Valley local who’d grown up in Cupertino; her grandparents had even worked an orchard in the valley before the computer revolution began. Her first job after college was at Goldman Sachs, working on startup IPOs. Later in the 90s, she went to business school and, via a connection made there, co-founded what she later described as “an advertising, tracking, and measurement company,” called Harmonic Communications. Her co-founder also worked at the venture capital firm Sequoia Capital, so funding wasn’t a problem. At some point, Andreessen joined the board of Harmonic and the pair hit it off. Bianchini sold her company to the ad agency Dentsu in early 2004, so luckily she was looking for her next new thing at the same time Andreessen was getting restless at Opsware.

The initial target audience of Ning was one that Andreessen was very familiar with and had favoured for his previous two companies: developers. A popular term amongst bloggers at the time was “social software,” suggesting that the mechanics of social networks could be programmed into any app by a developer. So Ning was, at the beginning, just as much of a business software company as Opsware (albeit higher up the stack). Bianchini later described Ning as “a programmable platform for building social networks [and] social applications.”

So what was the inspiration? Facebook had started the same year as Ning, but it was still virtually unknown outside of US college students. Andreessen hadn’t yet met Mark Zuckerberg (that would happen in 2005). A bigger influence was probably LinkedIn, a business social network that had launched in 2003. Sequoia Capital had led its Series A investment round at the end of 2003, and both Andreessen and Bianchini were friends with the founder, Reid Hoffman. LinkedIn ticked over one million users in the second half of 2004 and its growth trajectory was already exponential; by mid-2005, it would be 3 million. Even though Ning wasn’t the same type of application as LinkedIn — the latter was intended to be used by ordinary people — it had all the social software features that Andreessen and Bianchini wanted to have in their own platform.

LinkedIn screenshot, November 2004; via vefsafn.is

In a Wired interview in 2012, Andreessen said that at the time he started Ning, he was fascinated with Reed’s Law. It’s a form of network effects, stating that a network becomes more valuable when people can easily form subgroups to collaborate. “For any group of size n, the number of subgroups that can be assembled is 2n,” said Andreessen. So the initial idea of Ning was to allow users to create “social apps” for groups. “Friendster hadn’t worked, MySpace was just getting a little bit of traction, and Facebook was still at Harvard,” he explained. “What we knew worked were focused applications: Craigslist, eBay, Monster. So our idea was to bring social into these domains, in the form of apps that groups could run for themselves: their own job boards, their own selling marketplaces, and so on.”

It was only later on that this idea of social apps for groups was turned into the larger idea of “building your own social network.” But first, Andreessen and Bianchini had to build the platform.

Support Cybercultural

Cybercultural is a free newsletter, but you can also become a premium subscriber for £5 per month or £48 per year. Paid subscribers will receive the occasional bonus post, plus a thank-you mention in the paperbook book version of Bubble Blog.